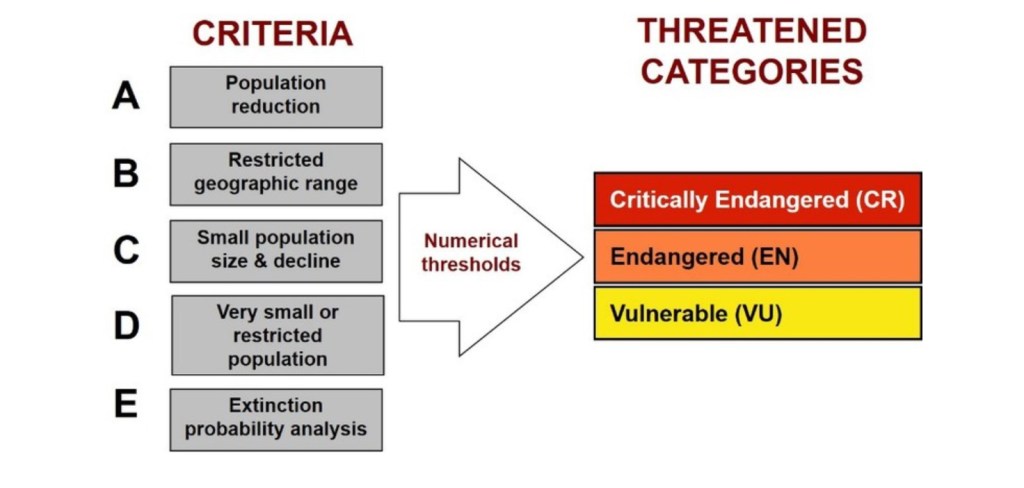

With as few as 550 living in an isolated population in South Luangwa, Zambia Luangwa giraffe (previously know as Thornicroft’s giraffe) is classified by the IUCN1 as vulnerable.2 This places it in the IUCN’s overall “Threatened with Extinction” category.

In December 2023 we were privileged to spend time in South Luangwa National Park as guests of Robin Pope Safaris under the care of Country Manager and guide extraordinaire Jonna Banda. However, our first sighting of Luangwa giraffe was while we were driving into the park to meet the team at RPS’ Luangwa Safari House.

Male Thornicroft’s Giraffe

A magnificent male stood and watched us as we neared the Luangwa Safari House.

He displays all the unique characteristics of Luangwa giraffe. Not necessarily obvious given that he is still probably 4.5 metres tall but he is the shortest of the giraffe sub-species; however, this still equips him for reaching the leaves on tall trees that no other browsing animals can reach. Only the tallest elephants, or those that have learnt the handy trick of standing on their back legs share the leaves in the giraffe’s part of the tree.

The second feature of the Luangwa giraffe which does not appear to be so consistent in other species is the colour difference between a male and a female. As can be seen in the first picture above the male is distinctly darker; both sexes start off the same pale colour but when the male is around eight years old his spots begin to darken, the last pale spots can be found around the neck area until he is about eleven but after that he is all dark.

We have seen dark spotted males elsewhere in Africa but have also seen pale spotted males in the same parks; according to an article in Science Direct “most, but not all, male giraffes darken with age (but) only a small proportion …. become very dark.”3 the Luangwa giraffe seems to buck this trend with the male always becoming dark.

Male giraffes are surprisingly aggressive towards one another. Battles over mating rights are ferocious with two 2,000 kg males swinging their long necks like muscular whips in an attempt to beat their opponent to the ground and into submission.

Both sexes have boney knobs, ossicones, on their heads but only the male uses them as a weapon so the easiest way to tell the difference between the sexes is that the female (on the left above) has hairy tufts on her ossicones whereas the male’s (on the right) are worn bald from fighting.

In the Luangwa giraffe there is another variation that can also be seen above; the fully adult male has boney ridges on his forehead giving his face a very lumpy look.

As a possible sub-species of the Masai Giraffe the Luangwa giraffe shares the same shaped spots.

Large, dark brown spots shaped like vine leaves with jagged edges on a creamy-brown background.4

It is assumed that spots or patches primarily evolved as camouflage but they have a secondary and equally vital function. Each patch has a central artery feeding dozens of smaller blood vessels that branch out in a wide fan under the whole surface of the patch. When the branches reach the creamy-brown, pale background between the patches they connect to larger veins that circle and interconnect the patches.

The patch itself acts as a thermal window that dissipates heat in the blood as it moves through the myriad of tiny veins under the patch. During the day the giraffe sends “hot” blood to its patches to cool down but when temperatures drop at night it shuts off these vessels and keep the warm blood around its muscles and organs.5

With so much of the world’s wildlife threatened and so many iconic African animals in the danger zone of extinction perhaps it is not surprising that giraffe being threatened doesn’t make the headlines. However, in the last forty years giraffe numbers have fallen by around 30% and in the same period they have disappeared or, all but disappeared, from parts of their historic range.

Many sub-species, including the Luangwa giraffe are threatened and only one, the Angolan Giraffe is classified as “Of Least Concern”. We all know how we got here and we know that there are national parks, wildlife reserves and an army of rangers and conservations working to save what we have left.

However, it is still chilling to think that a unique sub-species, an amazing and very special animal that along with elephants, zebra and lion are part of every child’s image of Africa has less animals left in the whole of Africa than the number of passengers you will be with on intercontinental flight if you fly to Zambia to see them.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Footnotes and References

- IUCN – The International Union for Conservation of Nature “Established in 1964, the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species has evolved to become the world’s most comprehensive information source on the global extinction risk status of animal, fungus and plant species.” https://www.iucnredlist.org/about/background-history ↩︎

- Giraffe Conservation Foundation 2018 IUCN Red List Update. Accessed 21/3/24 at GCF-IUCN-Red-List ↩︎

- Madelaine Carles, Rachel Brand, Alecia Carter, Martine Maron, Kerryn Carter, Anne Goldizen 2019 Relationships Between Male Giraffes’ Colour, Age and Sociability. Science Direct. Accessed 21/2/24 at science-direct-giraffes-colour ↩︎

- Giraffe Conservation Foundation. Africa’s Giraffe. Accessed 21/3/24 at GCF-Africa-giraffe ↩︎

- Quentin Fogg & Harriet Edmund 2023 Why Giraffes Have Spots. Accessed 21/3/24 at Uni-Melbourne-Giraffe-Spots ↩︎

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.