There are three species of zebra, the Plains zebra, Grevy’s zebra and the Mountain zebra and then there are several sub-species of Plains zebra and two of Mountain zebras. There might be as many as nine different types of zebra and seven of those are named after people. Who were the people who gave their names to a stripy horse?

I began looking at all seven but Richard Crawshay was very elusive and I became absorbed with tracking him down. He turns out to be a fighting soldier, policeman, colonial administrator, big game hunter, the first game protection officer in Kenya, artist, naturalist, lepidopterist and ornithologist; just your average Victorian in Africa.

This is part of his story.

Crawshay’s Zebra and Captain Richard Crawshay 1862 to 1955

Crawshay’s zebra (Equus quagga crawshayi) is one of six subspecies of Plains zebra; it is distinguished by its dense black stripes, lack of shadow stripes and narrow white interspaces. It is very stripy indeed with black bands extending right down to the hooves, up its ears, down most of the tail apart from a black tip and under the belly.

Apparently it can also be distinguished by the lack of an infundibulum among its lower incisors; however as they are notoriously bad tempered with a kick that can kill a lion and plenty of sharp teeth at the other end it may not be a heathy choice to look too closely inside its mouth.

Crawshay’s zebra ranges east of the Luangwa River in Zambia includes South Luangwa National Park, Malawi, south-eastern Tanzania from Lake Rukwa east to Mahungoi, and northern Mozambique as far south as the Gorongoza district.

Plains zebra are not listed as threatened but they do come under pressure from all the normal threats such as loss of habitat and conflict with farmers as well as still being trophy hunted for their skins.

So, how did this zebra get its name?

Richard Crawshay was born in Devon in 1862 the eldest of five brothers. He graduated from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst and joined the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, a regiment of the British Army originally raised in Dublin.

He served with the regiment in Natal which opens the intriguing but perhaps unlikely possibility that he was part of the “small force” including the 6th Dragoons who escorted King Cetewayo back into Zululand in 1883 after his exile in England that followed his defeat in the Zulu War in 1879.

According to the Inniskillings Museum the 6th Dragoons were stationed in Natal from 1880 until 1888 on pacification and garrison duties; perhaps a little understated as their time there included a significant engagement with Zulu forces in 1887. There is no record of Crawshay having being involved in the battle which took place in what is now the Imfolozi Game Reserve but he was still been serving with the regiment in Natal at that time so it is likely.

Meanwhile 2,000 km north on the shores of Lake Nyasa in what is now Malawi conflict was escalating between the African Lakes Company and Swahili-Arab slave-traders based at Karonga and Kota-Kota, now Nkhotakota. Harry Johnston, the British consul in Mozambique, took it upon himself, without the support of the British Government, to persuade an Indian Army officer, Frederick Lugard, who happened to be there on leave at the time to raise a private army funded by the African Lakes Company to proceed to Karonga and suppress the slavers.

According to Doctor Wordsworth Poole who was working for the African Lakes Company around Lake Nyasa from 1895 to 1897 Crawshay took leave but “practically deserted” from the army to join Captain Lugard’s expedition to to destroy Mlozi bin Kazbadema, the most powerful slave-trader in the region who operated from his base at Karonga on the northern shores of the lake.

Captain (later Lord) Lugard, set out from Mozambique in May 1888 with a tiny private army, made up of just three real veterans, and nine “wild men” and then gathered a few others on the way. He arrived in Karonga with just 24 men.

Like many localised conflicts that sprung up across Africa as Europeans endeavoured to gain control of areas that were the fiefdom of previous colonisers or indigenous people local resistance was far stronger, much better armed and far better organised than anticipated.

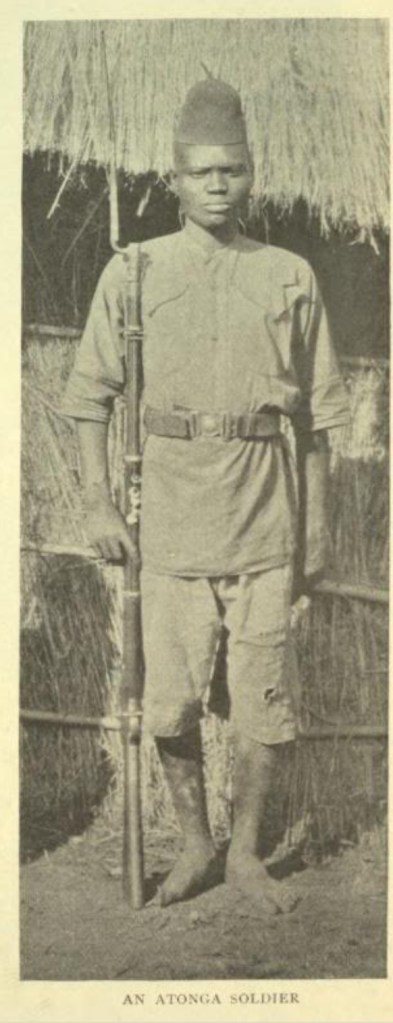

Lugard also did not understand the motivation of the two hundred Atonga levies who came up to Karonga with Alfred Sharpe, an African Lakes Company officer, and that made up most of his force; their interest in the whole affair having being severely diminished when ordered not to loot or capture women. In terms of preparation he was still teaching his native troops how to load and fire a rifle in the days before the first assault on Mlozi’s stockade. The first assault ended in disaster with several Europeans dead or severely wounded including Lugard who was unable to do anything except sit in the same chair for a month after the battle.

After two more disastrous attempts on the slaver’s stockade Lugard’s part in the Karonga or Slave War was over; from the outset his ill prepared force, riddled with disease, were out numbered, out gunned and out manoeuvred. In April 1889 after nine fruitless months at the top of the lake Lugard left for England.

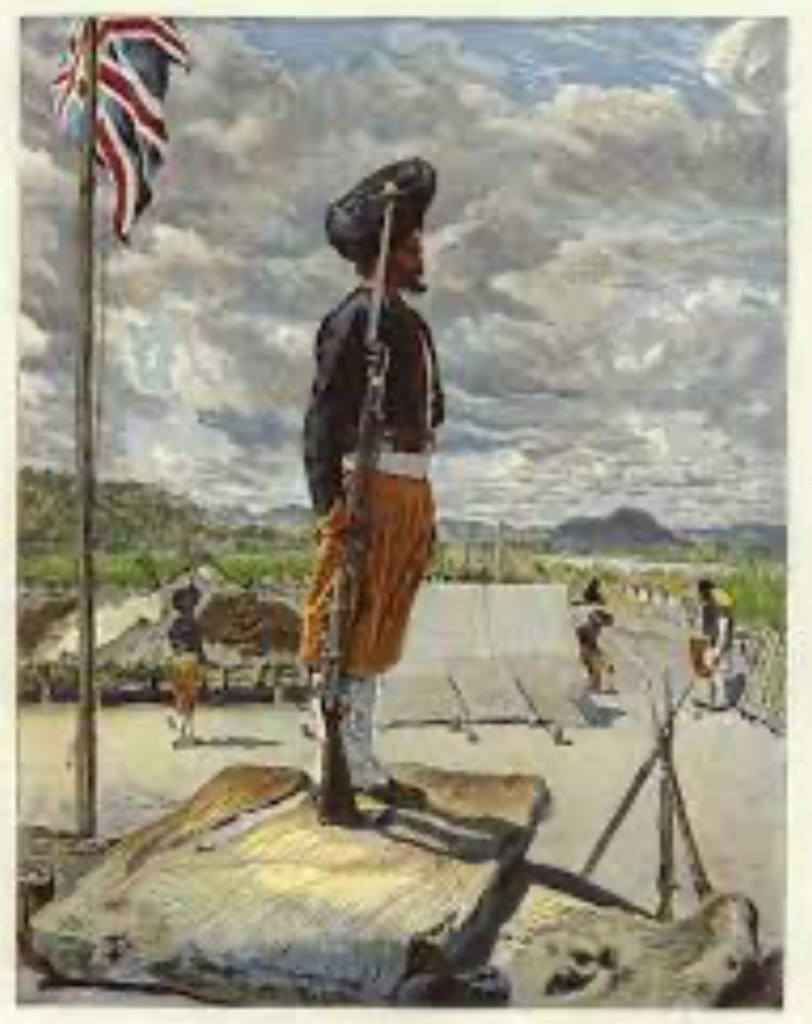

Crawshay, who we assume was at Karonga, now resigned from the army intending to hunt but instead, in 1890, joins the British South Africa Company’s police force. He was sent to Chienji (or Chiengi which is about 550 km northwest of Lake Malawi) on the east shore of Lake Mweru on the northwest border of what is now Zambia to set up a police post and in 1891 to built a fort at the same location. The fort was later moved to Kalungkwishi. He was given the nickname Kamukwamba by the Africans, a name that still occurs in Zambia and the DRC and translates as “born during troubles”.

And, troubles there were aplenty, this was not a peaceful period in either Zambia’s or Malawi’s histories. Three major Swahili Arab trade routes were still active around the lake. Through Karonga in the North, Kota Kota about a third of the way up the lake and through Mponda in the south. Yeo slave traders were running another route south through the Shire Valley to the Zambezi River.

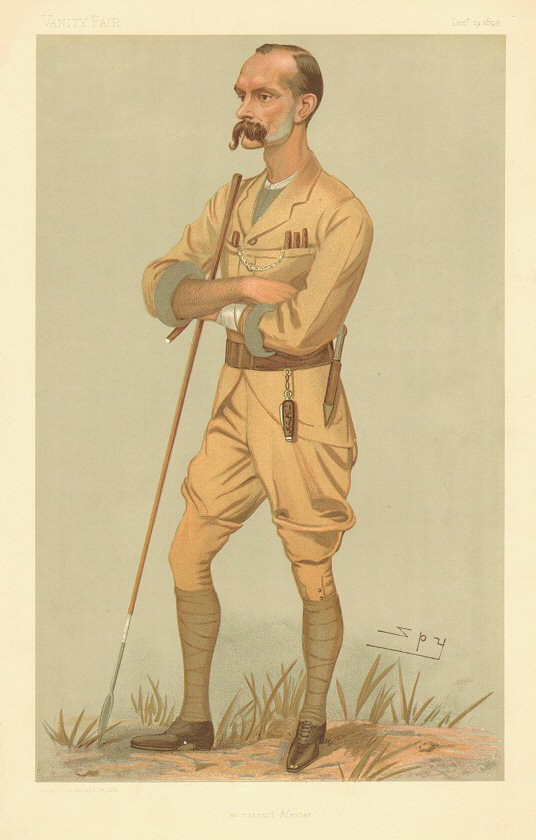

The next character to appear on the scene was a snobbish and bumptious, little man, no more than five feet tall with a squeaky voice and “an intensely effeminate manner”, an exhibitionist once described as “the little prancing pro-consul,” who appears to have been generally disliked by just about everyone who worked with him. However Harry Hamilton Johnston’s arrival changes everything; he was ambitious, energetic, brilliant, knowledgeable, an accomplished botanist and artist and capable of small talk in a dozen languages. Johnston, whom we last met in Mozambique, arrives in the Shire Highlands in 1889 as the first British Consul General and Commissioner of British Central Africa.

At this time the European population comprised 57 people, mostly missionaries, traders and a few early planters. Harry Johnston’s remit was to finally stop the slave trade and open central Africa for legitimate commerce. He began to form his administration and in 1891 recruited Richard Crawshay.

We know that Crawshay was initially based at Blantyre, perhaps at Mandala House which had been built in 1882 to accommodate the African Lakes Company managers but he doesn’t reappear in the records until 1893 when the African Lakes Company’s steam launch S.S. Domira gets stuck on a sandbank in the Shire River. This was a common occurrence, the Shire is notoriously shallow, but on this occasion it was stranded opposite one of Chief Liwonde’s villages and came under sustained attack thereby cutting communications between the Shire Highlands, including the important centres of Blantyre and Zomba, and Lake Nyasa.

Harry Johnston raises a relief column of Makua police, Atonga soldiers and three Europeans: Alfred Sharpe, Gilbert Stevenson and Richard Crawshay.

Led by Johnston they fight their way up river from Mpimbi to the Domira and for three days they come under intense fire from higher ground and are prevented from rescuing the steam ship. On the fourth day they are reinforced by Baron von Letz, who later became the governor of German East Africa, supported by an NCO, a Hotchkiss gun and twenty Sudanese soldiers.

A day later they were further reinforced by Commander George Carr and twenty sailors from HMS Mosquito, normally stationed on the Zambezi, plus two more men from the administration.

Chief Liwonde was defeated, his village captured and the S.S. Domira re-floated. Johnston, Carr and the sailors stay to build Fort Sharpe on one side of the river and Fort Liwonde on the other to ensure the Shire River remains open.

Richard Crawshay stays with the Domira until he is joined by a Frenchman, Lionel Decle, who was traveling through the protectorate studying ethnology and anthropology and who becomes the first person to travel from the Cape to the source of the Nile. Decle intends to travel north across the lake to German East Africa, modern day Tanzania. They get underway but within ten minutes hit a submerged tree trunk, damage the screw and run aground again. Three days later they manage to get underway and cross shallow Lake Malombe which lies just south of Lake Malawi.

The events surrounding the attack on S.S. Domira and its aftermath all happen close to, or even inside, what is now Liwonde National Park. See Travelogues-Liwonde_NP

They stop off at Fort Johnston, now Mangochi, for four days where Decle is impressed by the Sikh garrison.

After leaving Fort Johnston they make their way up Lake Nyasa stopping at Monkey Bay and Kota Kota where they meet Chief Jumbe a powerful ex-slave trader now just a trader having agreed a treaty with Harry Johnston.

The S.S. Domira drops Crawshay at Deep Bay where he will be the Collector and where he builds a fort to command the cross-lake ferry which is being used to transport slaves across the lake.

We know that Richard Crawshay is a hunter and indeed this is a pursuit he continues to follows for the rest of his time in Africa but, up until now, we have no sense of Crawshay the naturalist. Now, based at Deep Bay and later Karonga his administrative duties take him inland away from the lake to become the first European to see the Nyika Plateau and the lands between Lake Malawi and the Luangwa Valley in modern day Zambia.

From 1893 until as late as 1896 he appears to stay in the Deep Bay and Karonga area of the northwestern lakeshore. During that time he climbs to the Nyika Plateau on several occasions, probably the first European to do so, and travels west into what is now Zambia as far as the Luangwa river.

He is charmed and captivated by Nyika, commenting on its European climate, extensive grasslands and densely forested valleys. He “made a small but unique collection of butterflies” which he describes at some length in one of his reports to Johnston.

On another trip south of the plateau to hunt hartebeest, hunting being a pass-time much enjoyed by Malawi’s colonial administrators (see The Origins & History of Liwonde National Park), he casually describes walking past a male lion resting in the shade just 20 paces away from his path and puts the lion’s lack of interest down to them not having made eye-contact with each other.

In another anecdote he recalls hunting elephant on the shores of Lake Nyasa. After he had killed his first elephant he decided to sleep overnight between its legs and then cut out the tusks the next morning. He took no precautions and was surprised in the morning to find that a pride of lions had left spoor around the carcass but had not fed on it because, he assumes, of his presence. He says they came back and fed after he had taken the tusks.

We know that he traveled into Angoniland via the Nyika plateaufn4 and made a journey to investigate the slave trade to a place he calls Senga which he tells us is in the Luangwa valley seven or eight days on foot from Karonga. He believes that he is only the second European to visit the area and that the other one didn’t make it back alive. He collects some antelope heads, some shells and sixty butterflies before being chased out of the area by Senga slave traders.

Disappointingly I can find no mention of him collecting a specimen of what would be named Crawshay’s zebra. The nearest we get is when he describes stalking a “full-grown dark-maned lion” in the Henga valley which he says is three and a half days walk southwest of Deep Bay which puts it to the south of Nyika. The lion is striding along a game trail roaring at intervals and stampeding the game.:

“Hartebeests were sneezing, Reedbuck whistling, and herds of Zebra thundering about all over the place.“

His various reports and letters give us a real insight into the life of a colonial administrator; Crawshay was still a young man and, typical of his time, was the administrator, magistrate, policeman and the face of empire across a huge swath of central Africa, walking on two or three week round trips into uncharted territory to talk to tribal leaders who may or may have been friendly.

Doctor Poole tells us that he “so loved Africa that he returned early from leave having a spleen as big as his head” he was invalided out of Nyasaland in 1896.

Just before he left the protectorate to return to England, he sent a collection of butterflies he had made in Nyasaland to the Zoological Society in London.

I assume that Crawshay spent some time in England recovering before re-appearing in what is now Kenya in 1897 as an Assistant Collector with the East Africa Police based in Kitui, a town about 100 km east of Nairobi.fn3 It appears that he was at Kitui for about two years before being posted to Kikuyu in June 1899 and Nairobi in December of the same year where by 1900 he was the officer in charge of the Railhead Police Post.

Before 1900 there was no town at Nairobi “the place of cold water”, wildlife including lions and rhino roamed here and young Masai warriors hunted lion to graduate to manhood. Michael Thomason says that Kenya “was no place for the faint-hearted” with a handful of Europeans governing 2,600,000 Africans that they barely understood.

In 1902 Crawshay wrote a twenty-six page, paper for The Geographical Journal describing “the country, people, fauna and flora” of Kikuyu based on his experiences of living there. This paper, more that any other document or reference that I have found provides the greatest insight to Crawshay’s view of the world and more specifically of Africa. His colourful, descriptions of the landscapes and people of Kikuyu written in an easy conversational style show us a man with a fine eye for detail, in love with Africa and displaying an empathy towards its people that is probably unusual for his time.

He describes the Kikuyu people:

“A race of inhabitants of splendid physique, of a high order of

intelligence, agricultural and pastoral in their habits, industrious,

pugnacious amongst themselves, suspicious of and disposed to be hostile

to all strangers; like the Zulu group of Bantu, quick to defend the

honour of their women, but showing an open manly disposition to

those who deal fairly with them and gain their confidence and friend-

ship by tact and forbearance.”

“I have travelled and resided for long periods amongst many Central African tribes, but nowhere have I been so impressed by any one of them as by the Kikuyu – their solid physique, their independent spirit, and their open manly nature.”

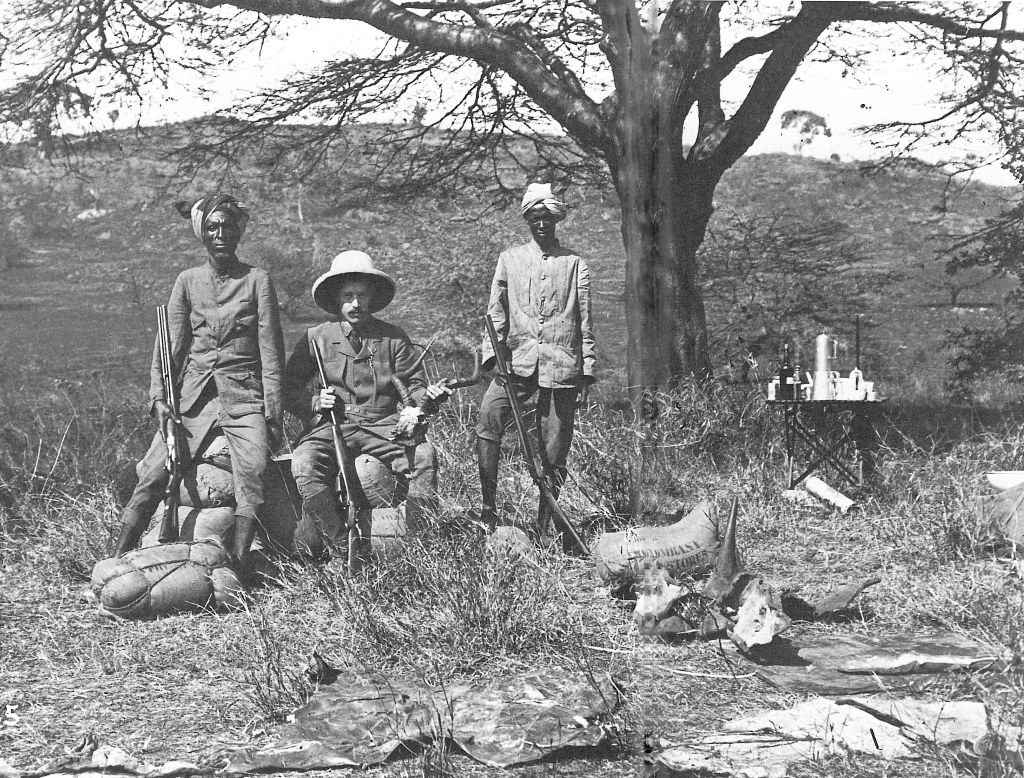

In the absence of any photograph or sketch of Crawshay we are given one tiny clue regarding his appearance when he tells us he wears a “scarlet yachting-cap” in the early mornings and late evenings in Kikuyu. He says that his time in Kikuyu is the “pleasantest time” he has had in seventeen years of living in Africa:

“Life passed quietly enough at Fort Smith, yet not unpleasantly. My time was occupied with official duties, gardening, natural history collecting, francolin-shooting, and in adding to my vocabulary of the language. Yet living in a tent in a climate at all times cool and moist, often positively raw, what with rain, mist and heavy dews, the weather proved a severe ordeal.”

To read his detailed account of life in Kenya, even for those of us who know something of Africa, is to enter a world that bears little resemblance to our own. He travels into remote areas where no other European has been to meet and negotiate with tribal leaders accompanied by:

“one or two men, and no more defensive weapon than a specimen gun or a butterfly net.”

He only encounters violence once and even then from an angry drunk rather than from a premeditated attack.

The turn of the century is the dawn of the great game reserves to “preserve Africa’s fauna by implementing strict bag limits.” fn1 The British government’s policy had been to establish reserves but leave them un-policed, an approach that was eventually recognised as untenable so in around 1900, Richard Crawshay was appointed as the first Game Protection Officer in what is now Kenya to “devote attention to this matter”.

Without the help of a single ranger Crawshay was responsible for game preservation over 48,000 square miles, approximately the size of England, split across two reserves imaginatively named the Northern Reserve and the Southern Reserve.

Clearly Crawshay had his butterfly collecting net with him throughout those early years in Kenya; he sent the Zoological Society butterflies that he had collected whilst traveling in Masailand towards Mount Kenya and in March 1898 he wrote to the society from Kibwezi which is just east of the Chyulu Hills and northwest of what is now Tsavo East N.P. which would have been part of the Southern Reserve.

In 1901 the first Ranger for Game Preservation, Blayney Percival, was appointed to replace Crawshay. We can better understand how different this role was to a 21st century ranger when we find that in 1927 Percival published a guide to big game hunting in the game reserves he had protected.

According to the British Museum “in 1899-1902 Crawshay rendered important services to the British government in the Boer War”. He leaves one tantalising clue in his paper about the Kikuyu mentioned above; he acquires sweet pea seeds from a fellow gardener which he plans to try at his camp but they are:

“destined to occasion yet one more pang of regret when the time arrived for me to leave all, preparatory to going south to join the war.”

I can find no trace of his role in the South African or Boer war but perhaps there is a link between his service there and Fredrick Smith, the army vet, who crops up later in Richard’s story as a close friend and who is unlikely to have met him in either Malawi or Kenya.

One assumes that Crawshay left Kenya and headed to South Africa in 1901 but unfortunately he doesn’t reappear in the record until 1904 by which time he is in South America.

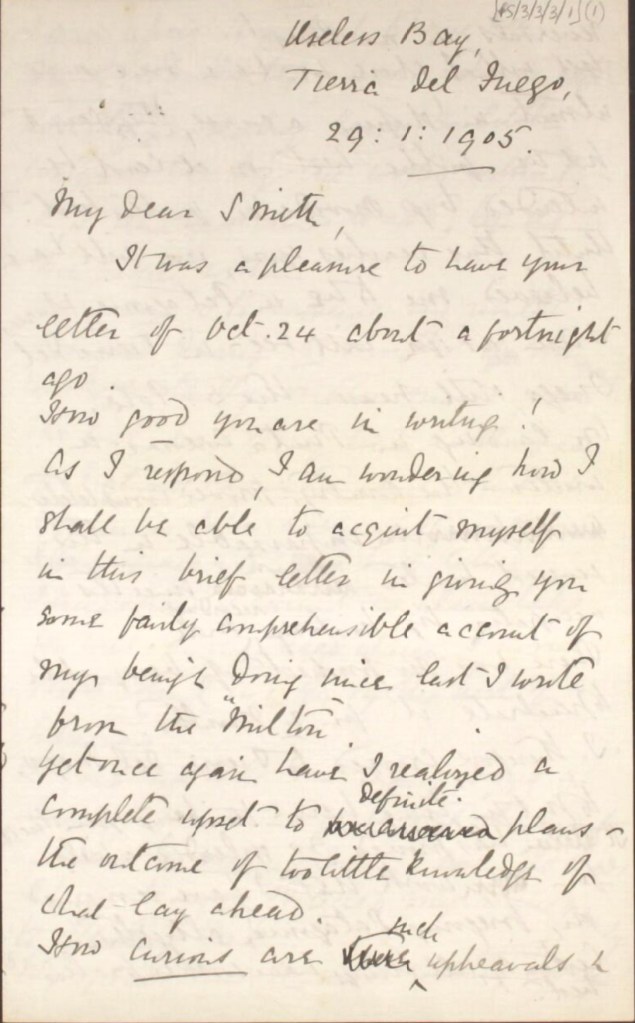

Thanks to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons history project there are three letters written by Crawshay to Major General Sir Fredrick Smith.fn2 These letters give us a tiny glimpse into his mind.

In January 1905 he writes a letter from Tierra del Fuego which telling Smith that he arrived in Punta Arenas in August 1904 and has subsequently traveled to Tierra del Fuego through severe winter weather and where he has now become very interested in the bird life which he describes in some detail.

He says that he will be back in England in early 1906. Near the end of the letter he says that he was philosophical about what appears to be the breakdown of a relationship with a lady and this leads him to describe himself:

“Any woman who controls my destinies to the extent of being a partner in marriage must take me for what I am & I know I am — a solid honest serious straight man who will not forego what he conceives to be his responsibilities in life ……. [she] cannot see life things from anywhere near the same point of perspective“

By 1907 he was in England and living with his brother in Bedfordshire and in a letter to Smith talks of the two and a half years he had been working on his book The Birds of Tierra del Fuego following his expedition to that region.

The most interesting part of this letter is his distain as an “Old Great Game Hunter” for “young men shooting in England” sitting on shooting sticks with a cigarette in their mouths.

Fredrick Smith keeps Crawshay’s visiting card, dated 13th December 1907, amongst his letters.

Intriguingly it is attached to a scrap of paper upon which Smith has written:

“I wish I had kept crawshay’s delightful correspondence during his travels in Patagonia and Australia.”

So there we have it. Richard Crawshay fades from the record in 1907 leaving a tantalising clue that he also traveled to Australia. Perhaps someone will find a trail to follow there. We know he returned to the English west country in later life, he lived to the ripe old age of 93 and died in 1955 in Edge, Gloucestershire.

He and I overlapped on this earth for a couple of years yet imagine the difference in his world 1880’s to 1910’s century compared to my 1980’s, to 2010’s. I’ve lived to collect stamps of the Empire as a child and hear about de-colonisation as an OAP. Whereas he saw the beginning of the British colonies in Malawi, Rhodesia, Uganda and Kenya and within 10 years of his death the African countries he knew well, Malawi, Zambia, South Africa and Uganda had all, quite rightly, gained their independence from Britain. He very nearly saw the beginning and end of colonial Africa which puts into perspective what a short period in history it was.

Through a twenty-first century optic it is hard to understand Crawshay and his contemporaries. He appears to see no contradiction in being an avid hunter who shoots for sport yet considers himself a naturalist. Of course as evidenced by many museum collection the early naturalists killed millions of specimens of creatures large and small to bring back to Europe.

He was probably well educated and graduated from a prestigious military college; his later writings prove him to be an intelligent and perceptive man. He is a fighting soldier probably seeing action in the chaos that followed the Zulu war and after he leaves the army in the Karango war, the relief of the S.S. Domira and then in the South African War.

He loves Africa and works as a colonial administrator, the only European in remote isolated posts both in what is now Malawi and later in Kenya. His lengthy descriptions of the Kikuyu people suggests he likes Africans, he learns their languages and endeavours to understand them. We are told he practically deserts the British Army to go and fight slave traders with Lugard and we can interpret this either as Crawshay the adventurer or someone ready to risk his life to stop evil.

Of course he is a man of Empire, a Victorian army officer who only sees service in the colonies, because of this, no doubt, Crawshay’s zebra will be “de-colonised” but that will be a shallow victory as Crawshay, in his 19th century way, cared deeply about Africa, African’s and Africa’s flora and fauna. He deserves to be remembered.

He has a Zebra, a hare and a waterbuck named after him.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

References & Footnotes

- When looking at wildlife preservation at the beginning of the 20th century it must first be recognised that colonial governments were motivated by protecting game so that it could be shot, under licence, by Europeans. For more on this subject see my blog on the origins of Liwonde N.P. in Malawi – https://travelogues.uk/2024/03/05/the-origins-of-malawis-liwonde-national-park/ The first International Conference for the Preservation of the Wild Animals, Birds, and Fishes of the African Continent was held in London in April 1898 with representatives of Great Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Italy, Spain and the Congo Free State met for in London. Eventually they agreed upon a convention that set “bag limits”, promoted the creation of areas were hunting was prohibited, and setting closed seasons. However, the convention was never ratified because the Portugal and France refused to limit the exportation of what we now see as hunting trophies but the British government went ahead and revised Kenya’s game regulations in line with the ideals set out in the convention.

- Major General Sir Frederick Smith KCMG, CB, FRCVS (1857-1929) qualified as a veterinarian in 1876 and joined the army. He served in India, on the Nile Expedition and in the South African Wars becoming the Principal Veterinary Officer there in 1903. Before retiring in 1910 he was Director General of the Army Veterinary Service

- There is a possible mistake or at least some confusion about his record in East Africa. The Europeans in East Africa website details the Kenyan career of a CRAWSHAY, Richard Wood (Lieut.). Some aspects of this entry appear to be “our” Captain Richard Crawshay including his service with the Inniskillens, his role as a “temporary game warden” which other sources refer to as a Game Protection Officer. However it has quite different birth and death dates and shows him as being married in 1891 to Augusta Jane Boddam. My instinct, although it is hard to prove without accessing births and death records, that this website has records for “our” Richard Crawshay in Kenya but has then researched his birth and death on-line and matched him to the wrong person.

- This is surprising as Angoniland was to the west of the southern third of the lake so I wonder if he is using this as a general name for what we now know as northeast Zambia to the west of the Nyika plateau.

- Oliver Ransford 1966 Livingstone’s Lake: The Drama of Nyasa. London: John Murray

- Sir Harry H. Johnston 1923 The Story of my Life. accessed 25/3/24 at https://archive.org/details/storyofmylife00john/page/2/mode/2up

- Andrew Hall. Richard Crawshay 1862 – 1955 accessed 25/3/24 at https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Crawshay-52

- Inniskilling Museum. the Inniskilling Dragoons – A Brief History. accessed 235/3/24 at https://inniskillingsmuseum.com/the-inniskilling-dragoons-a-brief-history/

- Major G. Tilden. The British Army in Zululand 1883 to 1888. accessed 25/3/24 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/44228607?seq=1

- Northern Rhodesia Police Association. The British South Africa Police in North-Western Rhodesia. accessed 26/3/24 http://www.nrpa.org.uk/chapter-two-the-north-eastern-rhodesia-constabulary/

- Capt. Richard Crawshay 1904 Some Observations on the Field Natural History of the Lion. Published in Proceedings of The Zoological Society of London, in 1904, in volume 1904, pages 264-268. accessed 26/3/24 at https://biostor.org/reference/107730

- Dr. A.G.Butler 1896 On a Collection of Butterflies obtained by Mr. Richard Crawshay in Nyasa-land, between the Months of January and April 1895. accessed 26/3/24 at https://biostor.org/reference/107926

- Thomas Paul Ofcansky 1981 A History Of Game Preservation In British East Africa, 1895-1963. accessed 26/3/24 at https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=10522&context=etd

- A. Blayney Percival 1927 A Game Ranger’s Note Book. London: Nisbet & Co. Ltd

- Reuben Matheka 2005 Antecedents to the Community Wildlife Conservation Programme in Kenya, 1946-1964 accessed 30/3/24 https://www.jstor.org/stable/20723538

- Elizabeth Garland 2008 The Elephant in the Room: Confronting the Colonial Character of Wildlife Conservation in Africa. accessed 30/3/24 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27667379

- Helena Clarkson Vet History Letters to Smith from Captain Richard Crawshay. accessed 28/3/24 at https://vethistory.rcvsknowledge.org/archive-collection/fs-correspondence-between-smith-and-other-individuals/

- S. G. Williams 1959 The Old Police Posts of Nyasaland published in the Nyasaland Journal Vol. 12, No. 2, Livingstone Centenary Issue (July, 1959), pp. 31-38 (8 pages) accessed 30/3/24 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/29545851?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Richard Crawshay 1954 The Nyika Plateau: Richard Crawshay’s Impression in 1893 The Nyasaland Journal vol.7 No 2 pp 24-27. accessed 30/3/024 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/29545720

- Richard Crawshay 1902 Kikuyu: Notes on the Country, People, Fauna, and Flora. Published in the Geographical Journal Vol 20 no 1. accessed 30/3/24 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1775589

- Paul C. Lemon 1968 Biology of Zebra on Nyika Plateau published by The Society of Malawi Journal Vol. 21 No.1 accessed 30/3/024 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/29778169

- Colin Baker 1987 British Central Africa in 1893 and 1898 The Journeys of Lionel Decle and Ewart Grogan published by The Society of Malawi Journal Vol. 40 No. 1 accessed at https://www.jstor.org/stable/29778569

- Richard Crawshay 1894 A Journey in the Angoni Country published in the Geographical Journal Vol. 3 No. 1 accessed 30/3/24 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1773607

- Colin Baker 1988 The Genesis of the Nyasaland Civil Service published in The Society of Malawi Journal Vol. 41 No. 1 accessed 30/3/24 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/29778588

- Michael Thomason 1975 Little Tin Gods: The District Officer in British East Africa published in Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies Vol. 7 accessed 31/3/24 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/4048227

- Europeans in East Africa. Crawshay, Richard Wood (Lieut.) accessed 31/3/24 at https://www.europeansineastafrica.co.uk/_site/custom/database/default.asp?a=viewIndividual&pid=2&person=3928

- Kenya 63 The ‘Grey Company before the Pioneers accessed 31/3/24 at https://www.kenya63.org.uk/general/nairobi/pre-1900

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.