National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Michael Graham-Stewart Slavery Collection. Acquired with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund

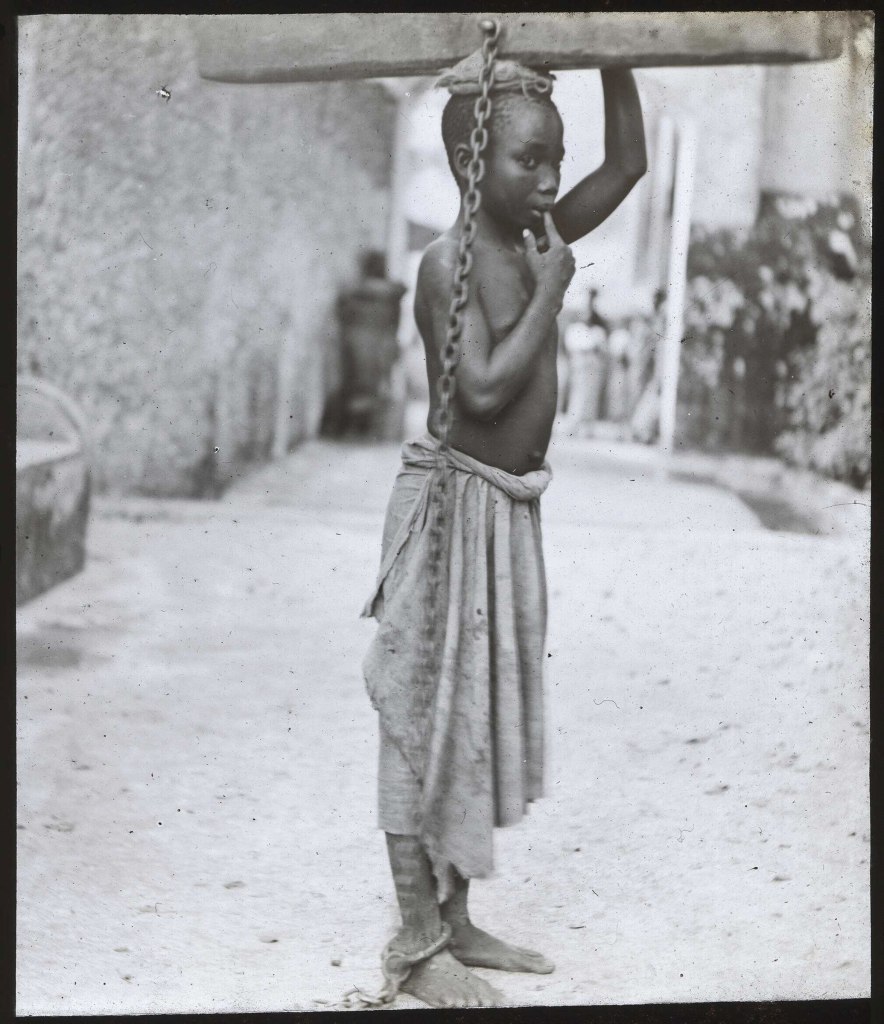

This photograph1 was taken in Stone Town, Zanzibar by an unknown missionary around 1890. The original is a lantern slide measuring just 83 x 83 mm, the width of a credit card, yet in that tiny space, it exemplifies the deep cruelty of the slave trade.

It shows a young boy, a child, dressed only in a merikani2, in this case a frayed piece of dirty cloth, that has been rolled at the waist to hold it up.

On his head, resting on a makeshift pad of folded cloth, is the heavy baulk of timber that the missionary estimated weighted 32 pounds (14.5 kg). The timber is attached to the boy via a heavy iron chain shackled to his ankle by an iron ring that must have been welded shut – this is not a casual arrangement – it is a brutal torture. We are told he is carrying the timber as a punishment for a “slight offence” against his Arab master.

He stands in an open area like courtyard, flanked on two sides by tall buildings, the courtyard appears to be a raised platform with a lower space like the top half of “D” beyond. There is a dark object that could be a public water supply to the left and what appears to be running water round the edge of the “D”. In the far background we see two or three men in Arab dress standing and looking towards the camera and an indistinct crouching figure that might be a woman.

The boy is handsome, even beautiful, not malnourished nor showing obvious signs of illness or injury; today you can see dozens of boys just like him playing on the beaches of Jambiani in front of the tourist lodges.

So why, of all the hundreds of photographs and engravings of East African slavery that I have seen,3 does this image stand out? Why does a print of this image hang, framed, on my study wall?

Just before his death in 1980. Roland Barthes, a French philosopher, wrote one last book4 in which he, a non-photographer, investigated the nature of photographs. He asked: why did some, excellent and interesting photographs of a subject just become homogeneous scenes whilst similar photographs of the same subject matter caught his attention in a profound and moving way?

He came up with the idea that a good, interesting photograph had, what he called studium, a latin word conveying a “general, enthusiastic commitment” on the part of the viewer. But a great photograph went beyond that and contained a punctum, an element that shoots out of the scene like an arrow and pierces the viewer.

For me the punctum, in the picture of the African child is his right hand, the outstretched index finger resting on his lower lip and his right eye that is looking sideways but not at the camera. The photographer must be close and was surely not an everyday sight so the sum of these gestures suggests the boy is deep in thought, bemused, bewildered, confused, trying to understand.

Perhaps lost in thought is a best description as this a little fellow is lost in every sense of the word. He is, in that captured moment, every child you have known and loved but alone, lost, confused and sad.

We cannot know his background, the slave market in Zanzibar, which had thrived since 1832 and where 40,000 to 50,000 slaves were said to have been sold every year, was closed in 1873 so there is no possibility than this child had been traded through that market.

However, slavery continued to be legal on the island until 1897 and slaves were smuggled onto the island and nearby Pemba to work on clove plantations, as domestic slaves, craftsmen and as concubines5. In 1895 the notorious slave and ivory trader Tippu Tip alone was said to own 10,000 slaves on his plantations in Zanzibar.

We cannot know this child’s fate. The odds were stacked against him. In 1897 the Sultan of Zanzibar was finally persuaded to declare most slavery illegal6 but it continued on the East African coast well into the 20th century.

Plantation owners in Zanzibar and Pemba kept the new abolition laws secret from their enslaved workers, concubines were legally enslaved until 19097, slaves were still being exported, smuggled, from East Africa to the Middle East in the 1890s and early 1900’s and some sources argue that the trade continued in one form or another until the 1960s or later. The Royal Navy rescued an enslaved pearl diver off Oman in 1931, a young man who had been kidnapped from Zanzibar as a six-year-old child at the turn of the century and taken to Arabia to be sold as a slave8.

This sad photograph of a desperate child helps to cut through the endless stream of statistics that swirl around any discussion of the slave trade. The number of people trafficked over the millennium during which the East African trade existed is clouded in mystery as few, if any, records were kept. Paul Lovejoy, a Canadian professor of History9 estimates 1,618,000 people were traded between 1800 and 1899, and if we accept Livingstone’s estimate, based on living with Tippu Tip, for every slave who reached the coast 5 others died en-route, 1.6 million quickly becomes around 10,000,000 people.

In my mind the ghost of that child still stands in a public square in Stone Town. He is silent, as are the other countless East and Central Africans sold into slavery, and their stories are nearly all untold. There is even an element of denial that it ever happened or happened on such a scale.

There has been too little research into the long-term, Africa-wide effects of this hideous trade. It set communities and ethic groups against each other, it fundamentally altered the demographics of sub-Saharan Africa10 which in itself had huge cultural impacts. It drove large groups of people to move across Africa creating intra-African colonisation and further displacement. It left the region vulnerable to conversion to alien religions and the suppression of the trade or clearing up the mess it left behind often became the excuse for colonisation by Europeans with both these factors then undermining, often destroying, localised traditional lifestyles and cultures.

The sad, bewildered child standing in a courtyard in Stone Town forcibly separated from his past and not knowing what his future holds is a metaphor for all this and more.

Epilogue

Since finishing this article I have learned that this child’s name was Cypriani Asmani who was six years old when the photograph was taken. The Photograph was (is?) exhibited in the Zanzibar Museum. I have not found any information online that can be corroborated as the various snippets posted about Cypriani tend to be contradictory.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Notes and References

- The Photograph : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slavery_in_Zanzibar_RMG_E9093.tiff ↩︎

- A merikani : an unbleached, cotton cloth probably imported from the USA which was “issued” to slaves in Zanzibar. Male slaves wrapped it around their waste and females tucked it under their armpits. They were later dyed and became known as kaniki. ↩︎

- For the last many months I have been researching the ivory trade in East Africa with a particular interest in the demise of Malawi’s great elephant herds. Early in that research I read E.D.Moore’s 1931 seminal book “Ivory the Scourge of Africa” in which he argues that ivory and slave trading were inextricably linked. I quickly discovered that the more you research ivory hunting and trading the more you learn about the East African slave trade which so horrified Dr David Livingstone when he sailed up the Shire River in 1859. The results of some of that research can be found at https://travelogues.uk/2024/05/21/the-fall-rise-of-malawis-elephants-part-1-before-the-fall/

https://travelogues.uk/2024/05/31/the-fall-rise-of-malawis-elephants-part-2-the-nightmare-years/ ↩︎ - Barthes, Roland (1980) Camera Lucida. Originally published in French by Editions du Seuil. My edition was published by Vintage in 2000. ↩︎

- Concubines were sex slaves. It was an integral part of 19th century Zanzibari culture where men purchased women for the purpose of sexual relations outside of marriage. ↩︎

- The law declaring slavery illegal had certain caveats including specifically excluding concubines on the very thin argument that emancipating enslaved women who were unable to provide for themselves would lead to them becoming prostitutes. The reality was more to do with the British who had been the driving force behind the Sultan’s law felt that the practice of concubinage was too sensitive a subject to delve into. Concubines were not included within the abolition law until 1909. ↩︎

- See 6 above. ↩︎

- Hopper, Mathew (2008) Slavery and the Slave Trades in the Indian Ocean and Arab Worlds: Global Connections and Disconnections. https://glc.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/indian-ocean/hopper.pdf ↩︎

- Lovejoy, Paul (2000) Transformations in Slavery: A history of Slavery in Africa (2nd Edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press – available on line at https://archive.org/details/transformationsi0000love/mode/2up ↩︎

- New African (2018) Recalling Africa’s harrowing tale of its first slavers – The Arabs – as UK Slave Trade Abolition is commemorated https://newafricanmagazine.com/16616/ ↩︎

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.