© Steve Middlehurst

Eight years ago, when first arriving on the Isle of Wight, I visited the Alan Hersey Nature Reserve at Springvale for the first time. It is a small marshland reserve shoe-horned into one of the few pieces of the coastal strip that have avoided development in this area. There, standing in the shallow pond to the right of the path, was a white heron-like bird with a black beak, piercing eyes and large yellow feet. This was my first introduction to the Isle of Wight’s little egrets. They are a daily sight across the Island’s wetlands, on many of the beaches and in the inlets and estuaries that break up the shoreline. They often crowd together in a single tree or under an overhang along the coast.

A visitor might think that this is a common bird that has always been here and they were common here in the 15th Century and are common again but in between they disappeared for as much as 500 years.

Theirs is a story of decline, fall and recovery.

In 1988 the British Automobile Association (AA) and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) jointly published The Complete Book of British Birds. Ironically the little egret doesn’t feature amongst the descriptions and illustrations of what the RSPB’s then President Magnus Magnusson describes as descriptions and illustrations of “all the birds you are likely to come across”.

Ironic because the little egret played a starring role in the foundation of the RSPB and equally ironic because even when the society was formed in 1889 the Little Egret had been pretty much extinct in Britain and Ireland for hundreds of years.

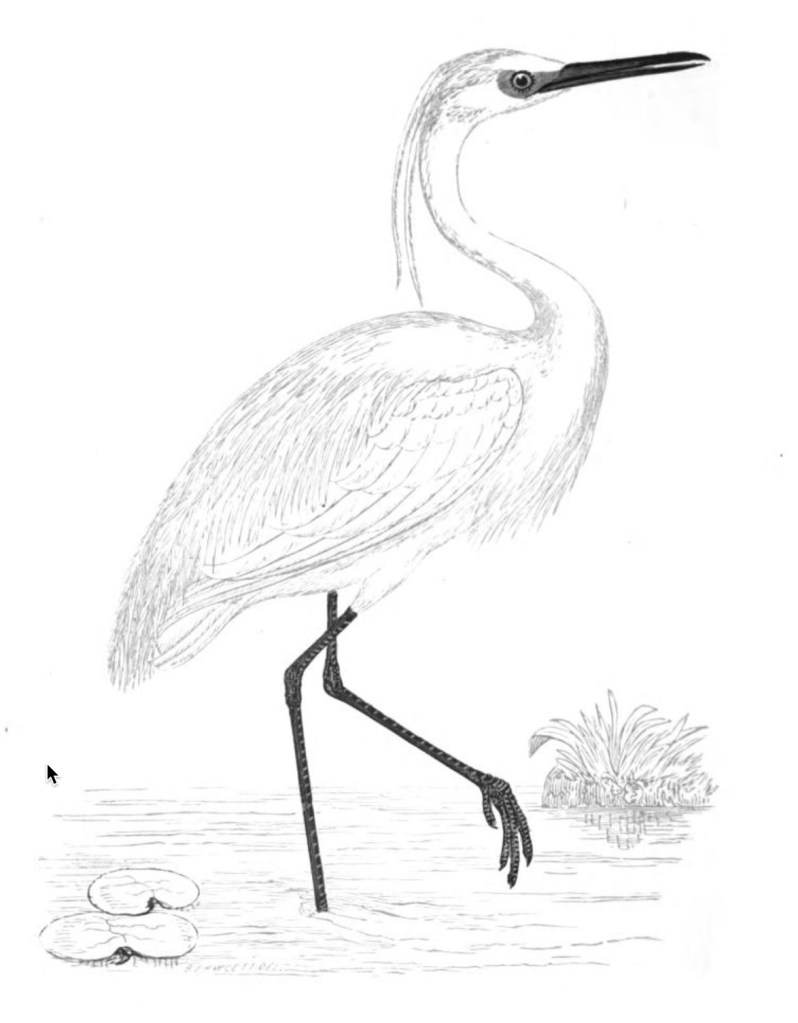

The Little Egret is a medium sized white heron standing between 55 and 65 cms tall; distinguishable from its larger cousins, the great white and the yellow-billed egrets, by its yellow feet and black bill. The one on the left is in Liwonde NP, Malawi.

It is very similar to the snowy egret which is widespread in the Americas. The cattle egret is smaller with olive legs and a yellow beak.

© Steve Middlehurst

The egrets are a highly successful group of birds thriving in one form or another across Africa, Australasia, Asia and Southern Europe and, in the case of the cattle and snowy egrets, in the Americas. However, in Britain the only one of the family that has been more than an occasional, blown-off-course, visitor is the little egret which appears to have been common until late medieval times, then extinct, but now recovering and, indeed again common in some places such as here, on the Isle of Wight.

© Steve Middlehurst

Reliable ornithological records are rare before the 19th century so we are mostly reliant on anecdotal evidence. They were part of the coronation feast of King Henry VI in 1429 and when, in 1465, George Neville was enthroned as Archbishop of York he invited 900 of his closest friends to a banquet where among other delicacies he served 1,000 egrets.

We can safely assume that, even with so few references, the little egret was one of many birds being regularly hunted for food in medieval Britain and this was no doubt partly to blame for the reduction in their numbers but it is also an indication of how common they must have been. Without refrigeration Neville’s 1,000 birds must have been hunted over a very short period.

© Steve Middlehurst

Britain once had had extensive areas of open inland water, marshes, fens, wet woodlands and bogs like the Somerset Levels and the Cambridgeshire Fens but also thousands of much smaller habitats on the floodplains of every river and stream. These wetlands supported a wide variety of mammals and birds such as beavers, otters, water voles, white-tailed eagles, little egrets, cranes and night herons. We were already draining the Somerset Levels when the Romans were here, and medieval monks continued to devastate that particular area.

For the next many hundreds of years we mostly drained comparatively small areas until the largest, landscape changing projects began in the 17th century and continued until the modern day. Some estimates suggest that Britain has lost 75% of its wetlands since 1700. This loss of habitat clearly had a significant negative impact on the many birds that relied on those wetlands including the little egret.

But, hunting and loss of habitat were only partly to blame. We know that in the early 1300s average temperatures in Britain fell by 2oC as the Northern Hemisphere entered the Little Ice Age.

For a hundred years after the “Great Frost” of 1608 the River Thames froze on a frequent basis.

The people of London responded by holding frost fairs on the frozen river. In 1684 the stalls selling food and drink stretched for three miles between London Bridge and Vauxhall catering to the crowds skating, sledging, playing football or just being entertained by puppet plays and fire eaters.

Temperatures began to rise again in the mid-19th century and have continued to do so ever since but by then the biodiversity of the British Isle had changed. There are very few sources that describe wildlife before, during and immediately after the Little Ice Age but we do know that some species were common or, at least, far more common in medieval Britain than they were are the end of the 19th century.

The demise of wolves, the lynx, cranes and wild boar had probably little to do with climate but perhaps the extinction of the white-tailed eagle was partly due to a well-documented decline in both salt and fresh water fish stocks as well as persecution by shepherds, gamekeepers and farmers.

© Steve Middlehurst

Perhaps we can look at this from the opposite direction and consider which birds are colonising Britain in the 21st century as the climate continues to warm or because temperatures are already too high in parts of Europe. The little egret is a leading contender and has been joined by the quail, hobby, little bittern and spoonbills all potentially colonising the south of England as well as alpine swifts, black-winged kites, cattle egret and the night heron that are now being spotted in Britain. One wonders how many of these were common during the last warm period before 1300 and are now in the process of re-colonising.

The little egret was assailed from all sides. They were being hunted for food, wetlands were being drained, and the climate was cooling. Longer and colder winters would have depleted their food supply and extended periods of frozen waterways would have prevented winter feeding.

By the 19th century the little egret was only very occasionally sighted in Britain; the Reverend E.O Morris writing in A History of British Birds reports eight sightings between 1816 and 1854.

There are other records of rare sightings in the 1800s including a stuffed specimen that was labeled as having been shot in Yorkshire in 1826 and a sighting on the River Exe in 1870.

In the early 20th century there continued to be rare glimpses of this pretty bird; the Historical Rare Birds website lists forty odd sightings between 1930 and 1957 including one as far north as the Outer Hebrides in 1955. However, the records support the argument that they were all but extinct in the British Isles in the 1800s and in the first half of the 20th century.

With its preferred habitat and climate disappearing in the North the little egret retreated south but in the mid 1800s they came under a new threat that jeopardised their existence worldwide.

Writing in 1832 Thomas Bewick reports that egret plumes were formerly used to decorate the helmets of warriors but says that they are now applied to a gentler and better purpose, in ornamenting the head-dresses of European ladies.

But, this gentler purpose evolved into a major and long-lasting fashion. Frank Chapman, an American ornithologist, recognised 40 native species on women’s hats during a single walk through New York in 1886.

Tragically for the little egrets in Europe and its close cousin the snowy egret in America their brilliant white plumage, especially the gossamer wisps of feather developed in the mating season, was in high demand among milliners across two continents. At its peak the London market alone was using the feathers from 130,000 egrets across a nine-month period.

© Steve Middlehurst

The plume trade was brutal and highly profitable. In 1902 auctions in London saw the plumes of nearly 200,000 “herons” sold at a price of around £7 an ounce when gold was trading at around £4 an ounce. Because the egret plumes demanded were those produced in the breeding season the birds were slaughtered on their nests leaving eggs to rot and young birds to starve.

Countless other birds from all over the world fell prey to this grisly trade. The naturalist W.H. Hudson observed 125,300 specimens of parrots on sale at a London feather auction in 1895. By the turn of the century millions of birds were being slaughtered every year: peacocks, hummingbirds, jays, bee-eaters, pheasants, birds of paradise, orioles, owls, ibis and toucans along with the egrets and parrots.

By the 1880’s more people were speaking out against the feather trade but it took three women in England to take direct action; Eliza Phillips and Margaretta Lemon formed the Fur, Fin and Feather Folk, and Emily Williamson (left) founded the Society for the Protection of Birds (SPB) in 1889.

They joined forces in the early 1890s and received royal assent in 1904 to become the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) Their objectives were twofold: to change the attitude of the end consumer and to convince Parliament to ban the trade.

The stories of the SPB’s campaigns and their counterpart in the USA, the Audubon Society, are long and complex. Legislation was passed in many different countries, the press picked up the story and helped the bird protection movements spread their message, emotive pamphlets, the social media of the day, were published and distributed and they were increasingly supported from the pulpit and in the classroom.

The plume trade did eventually die out. By the start of the 1st World War feathered hats had fallen out of fashion. The RSPB and the Audubon Society had impacted public opinion and forced governments to legislate, fashions had changed either because of this pressure or just because fashions always wax and wane and the supply of feathers dwindled as the targeted birds became less common.

But two things were certain; the plume trade had gone for ever and the little egret had become the symbol of these early conservationists.

After the First World War there were occasional sightings of little egret in Britain. The marvellous Historical Rare Birds website notes these records that reached recognised authorities. It is interesting that some of the earlier 20th century records include arguments as to whether the specimens were definitely wild birds as it was note that many were kept in captivity.

The bird remains a very occasional, and one must assume, blown-off-course visitor to Britain through the first half of the 20th century. In the 1950’s there were just 34 sightings but it was reported that 33 birds were present in 1960. It is interesting to track their return from the Mediterranean to Western Europe; in 1960 they formed a breeding colony in Brittany, then they re-appeared in Normandy, then by 1979 they were breeding in the Netherlands. They crossed the channel to England in 1996 and started breeding on Brownsea island, and by 2017 there were at least 1,000 breeding pairs across the UK.

Rather intriguingly in the last 20 years it has also bred in Barbados and Antigua although it hasn’t really established itself in either place as yet.

© Steve Middlehurst

This gorgeous bird has become common here on the South Coast, they are in the wetlands and on the beaches round the Solent and can be seen every day on the Isle of Wight, often in groups of a dozen birds or more. Clearly there are less far wetlands now than when it was last common in Britain so it seems most likely that initially hunting and then the cooling climate was most of the cause of its demise but with hunting probably playing a bigger role on the Continent.

It has became warmer and we have stopped killing them for either food or fashion and slowly but surely they are coming back and reestablishing colonies not just around our coasts but also inland.

Long may it continue.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Notes and References

- Stewart, John R (2004) Wetland Birds in the Recent Fossil Record of Britain and Northwest Europe. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224975633_Wetland_birds_in_the_recent_fossil_record_of_Britain_and_northwest_Europe

- Bewick, Thomas (1832) History of British Birds Vol II: containing the History and Description of Water Birds. Newcastle: Longman & Co. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.39458/page/n5/mode/2up

- Morris, F.O. (1850-1857) A History of British Birds Vol 5. London: Groombridge & Sons. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=eyoOAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PP8&hl=en

- Hessayon, Ariel and Taylor, Dan (?), The Original Climate Crisis – how the Little Ice Age Devastated Early Modern Europe. https://theconversation.com/the-original-climate-crisis-how-the-little-ice-age-devastated-early-modern-europe-178187#:~:text=Starting%20in%20the%20early%2014th,and%20communications%20to%20a%20halt.

- Climate in Arts and History. The Effects of the Little Ice Age (c.1300 -1850) https://www.science.smith.edu/climatelit/the-effects-of-the-little-ice-age/

- Raye, Lee (2023) Wildlife wonders of Britain and Ireland before the industrial revolution – my research reveals all the biodiversity we’ve lost. https://insideecology.com/2023/07/19/wildlife-wonders-of-britain-and-ireland-before-the-industrial-revolution-my-research-reveals-all-the-biodiversity-weve-lost/

- No Egrets: The Story of Fashion and Feathers Through Books. https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2020/10/fashion-and-feathers-through-books.html

- Souder, William (2013) How Two Women Ended the Deadly Feather Trade https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-two-women-ended-the-deadly-feather-trade-23187277/

- Ehrlich, Paul R., Dobkin, David S., and Wheye Darryl (1988) Plume Trade. https://web.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Plume_Trade.html

- Historical Rare Birds – Little Egret https://www.historicalrarebirds.info/cat-ac/little-egret

- British Trust for Ornithology (2024) Little Egret https://www.bto.org/understanding-birds/birdfacts/little-egret

- Birds of the World – Little Egret https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/litegr/cur/distribution

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.