- Introduction

- The West African Squadron

- The East Coast in 1800

- Early Measures

- Treaties and Laws

- H.M.S. Cleopatra

- 1808 to 1853 Conclusion

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

Between 1640 and 1807 approximately 12 million Africans were transported from the west coast of Africa to the Americas; around 3.4 million of those were transported on British Ships.

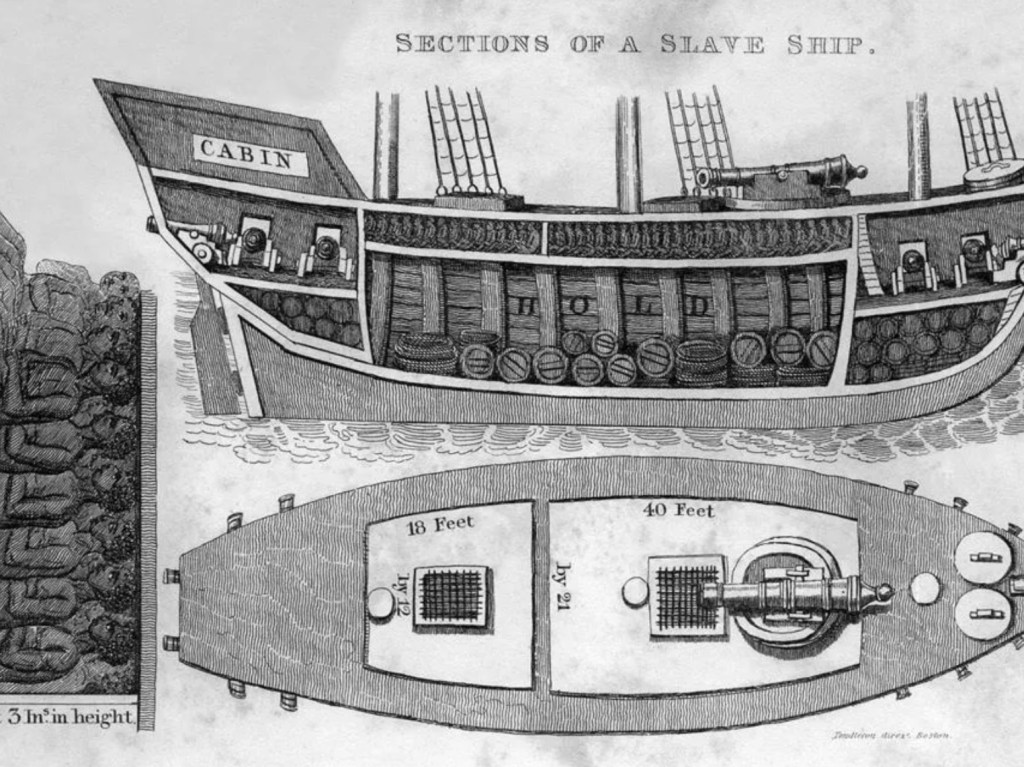

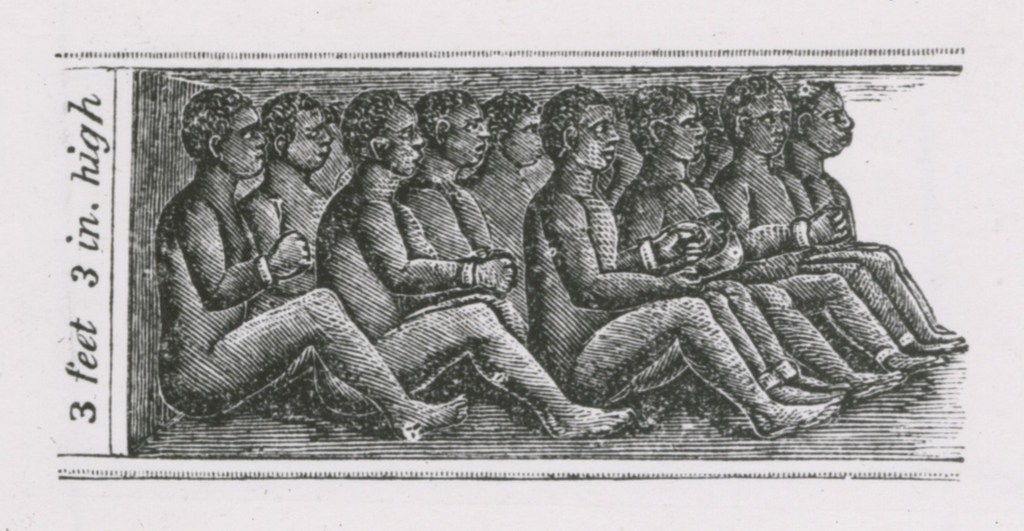

The abolitionist movement commissioned this Drawing to Raise Awareness of the Slave Trade.

In May 1787 the first meeting of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was held in London and the abolitionist movement quickly grew by mobilising unprecedented public support.

The Slave Act was passed by the British Parliament on 25th March 1807; from May 1st 1807 it became illegal for any British subject or anyone resident in Britain or her colonies, territories or dominions to engage in the slave-trade.

The West African Squadron

In 1808, whilst the Napoleonic Wars still raged in Europe, the British Admiralty gave orders to two ships, HMS Solebay, a 32 gun Frigate under the command of Edward Henry Columbine and HMS Derwent, a 16 gun sloop under the command of Frederick Parker to patrol the west coast of Africa from their base at Portsmouth. 1

There is little available information on the effectiveness of this little squadron which seems to have first left Portsmouth in October 1808. 2 In July 1809, 3 during what was probably their second voyage to the west coast of Africa, 4 Captain Columbine led an “expeditionary force” to reduce the French colony of Senegal which was being used as a base by Privateers. 5

In July of 1809 he wrote to the Admiralty to provide a preliminary report regarding the coast near Sierra Leone :

“He reports that he believes that the slave trade is being carried on much as before under the disguise of the Portugese and Spanish flags. The coast adjacent to his position is too dangerous for a ship of any size. If the slavers hear of a vessel of war approaching then they land and off load their slaves. On that basis the only way the Abolition Act can be implemented is by the use of smaller craft. Accordingly he has used a schooner and a boat and as a consequence has captured two slave vessels. He hopes the Admiralty will approve his approach as the only feasible way of enforcing the law particularly as it incurs no extra expense. 6

Columbine based himself at Sierra Leone and took command of HMS Crocodile. He reported to the Admiralty that on the 26th March 1810 his squadron captured a brig with 120 slaves on board of whom 38 were enlisted into the Royal African Corps. Later they captured the Marianna off Sierra Leone with 186 slaves on board and the American schooner, Esperanza, with 91 slaves on board. 7

Another vessel was detained by HMS Tigress and two others by Crocodile and later that year a slave ship bound from Cuba with 57 enslaved people onboard was captured by Crocodile and taken into Sierra Leone.

On 19th June 1811, 2,600 kms west of Lisbon and 3,200 kms from Portsmouth, their destination, Lieutenant John Filmore appointed himself as acting Commander of HMS Crocodile 8 “in the room of Commodore Edward Henry Columbine deceased”. Edward Henry Columbine was buried at sea and the first chapter of the West African Squadron came to an end.

The squadron under various names and commanders continued to patrol the Atlantic until it was absorbed into the Cape of Good Hope Squadron in 1867. It freed around 150,000 slaves at a cost of the lives of over 1,600 British sailors, roughly 10% of sailors on patrol each year.

The East African Squadron

The East Coast in 1800

John Cary’s 1805 map of Africa perfectly depicts the European view of Africa as an empty continent.

On the west coast there are several settlements and states stretching inland as far south as the Congo. The Dutch colony at the Cape is shown in some detail but, apart from the Portuguese trading posts on the Zambezi River the east coast is mostly a map of river mouths and a few coastal towns.

The Mozambique Channel was the “inner passage” to India and the slave route to Brazil. To the west was the Portuguese controled coast of Africa with their trading ports at Mozambique island, Quelimane and Sofala and to the east lay Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, Mauritius, Réunion and the Seychelles.

Gerald Sandford describes the coast:

“Nowhere between Brava and Sofala had there been any substantial European settlement. South of cape Delgado, Portuguese Maçambique was simply a tattered coastal ribbon marked by the occasional decrepit fort.” 9

At the northerrn end of the channel the Comoro Islands offered plenty of hidden bays that were the favoured haunt of French and Portuguese pirates

Early Measures

After the Slave Trade Act was passed in 1807 the British were keen to quickly ascend to the moral high ground and stop other nations from engaging in the trade. There was also a realisation that passing the act did not stop British involvement in the trade. 10 A naval squadron comprising a frigate and half-a-dozen brigs and sloops was based at the Cape with the intention of intercepting slavers and landing freed slaves at the Cape Colony but the squadron was neither capable of clearing the Mozambique Channel of Arab and Sakalava slavers nor clearing the French and Portuguese pirates out of Comoro Islands.11

By 1813 the Royal Navy’s squadron based at the Cape Station comprised a third-rate battleship, three small frigates and two sloops to patrol a vast area that stretched from the South Atlantic in the West to the Indian Ocean in the East. However, between 1808 and 1816 the Cape Squadron intercepted 27 ships and freed over 2,100 slaves. 12

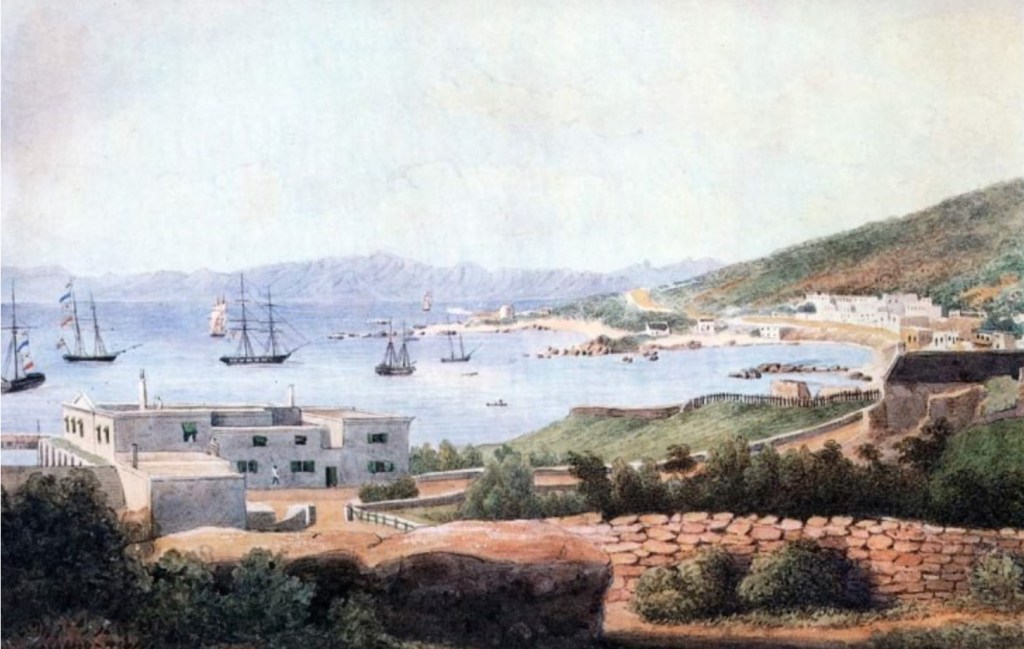

William John Huggins National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

In 1815 St. Helena became the island prison for the former Emperor of France and the Cape Station moved there under the command of Rear-Admiral George Cockburn, with his flagship Northumberland, two frigates, six sloops and a troopship. The squadron’s “first and most important” role, which kept it here for the next six years was to guard St. Helena and Napoleon. As St Helena lies 1,000 miles south-west of Africa this inhibited the squadron’s anti-slavery activity on the east coast of Africa and in the Indian Ocean.

A remarkable level of complacency seems to have existed at the Cape Station in the 1820s and 30s. Commodore Christian, in 1826, believed that the slave trade “did not amount to very much” whilst in 1836 Commodore Schomberg ordered a sweep of the Mozambique Channel and was able to reassure the Admiralty that the slave trade involving Madagascar did not exist “in any important degree.” 13

Treaties and Laws

An additional challenge to the anti-slavery squadrons came about as a result of the end of the Napoleonic Wars with countries no longer willing to accept Britain intercepting and searching ships sailing under their flags. The British Government embarked on a long and slow process of signing treaties with individual countries to allow the Royal Navy to stop and search non-British merchantmen.

The Anglo-Portuguese treaty in 1810, in which the Portuguese agreed to restrict its slave-trade to its own colonies, was the first of many attempts by British diplomats to stop the exportation of slaves from Africa. However the obvious limitations of the agreement typified the complex environment that was created by a succession of such treaties that Royal Navy Captains had to negotiate.

In clause 10 of the treaty the Portuguese agreed to bring about the “gradual abolition of the slave trade” but it allowed Portuguese subjects to trade for slaves “within the African dominions of the Crown of Portugal” and where the slave trade had not been “discontinued and abandoned by” a European power “which formally traded there”. On the east coast of Africa this appears to allow the Portuguese to not only trade from their own ports but with the whole of the Swahili coast. 14 In 1817 a further treaty limited the Portuguese to participating in the trade in the southern hemisphere which did little to stem the flow of slaves from east Africa to Brazil as eveything south of Mount Kilimanjaro is in the southern hemisphere and encompassed the whole area the Portuguese were harvesting.

In practice these treaties did little or nothing to suppress the trade, in fact the South Atlantic trade to Brazil grew in the years following abolition with over 550,000 slaves leaving Africa in the 1820s. It was not until 1839 that the British government took the significant step of allowing the Royal Navy to intercept any slaver bound for Brazil, regardless of the flag it was sailing under, if it was either carrying slaves or fitted out for that purpose. 15

For the first time since abolition the Royal Navy could reach beyond individual treaties to intercept any potential slave ship.

H.M.S. Cleopatra

The Ship’s Chaplain

In September 1842, the Reverend Pascoe Grenfell Hill 16 was in Rio de Janeiro serving as chaplain aboard H.M.S. Malabar of seventy-four guns. When H.M.S. Cleopatra arrived he was given permission to transfer and join Captain Christopher Wyvill’s command which was under orders to sail to the Mozambique Channel via Cape Town and Mauritius.

At the beginning of December 1842 H.M.S. Cleopatra left Mauritius 17 and proceeded to the Mozambique Channel with orders to disrupt the slave trade.

At this stage there was no known slave trading from Mozambique Island but it was still prevalent at the other Portuguese ports of Quelimane and Sofala further south.

Many of the rivers on this coast have a sand bar across their entrance and Quelimane was no exception; slave ships would wait outside the bar while flat-bottomed boats brought enslaved people out from the town and across the bar. While Cleopatra was patrolling further south H.M. Brig Lily forced a slaver ashore at Quelimane and cut out two others; by the time Cleopatra was back on station Lily was taking her prizes to the Cape.

On April 12th Cleopatra spotted a suspicious looking brigantine flying a Brazilian flag north of Quelimane. 18 They chased her down whilst firing fifteen to twenty shots to bring her to heal. She was the 140 ton Progresso out of Brazil and now returning to Rio.

On boarding they found 447 slaves 19 who, having seen the British coming up, had managed to overwhelm their captors and take over the ship. They were busy helping themselves to food and drink while knocking off their fetters

Wyvill sent Progresso back to Cape Town with a prize crew including the Reverend Hill and his servant along with a Lieutenant, master’s mate, quartermaster, boatswain’s mate and nine seamen.

Far more of the freed slaves were unwell than the sailors had originally thought; emaciated, suffering from dysentery, some with a virulent rash that they had initially mistaken for smallpox and several with ulcerated wounds. Their horrific journey from the coast was evidenced by suppurating wounds as a result of floggings, septic bite wounds and feet infected with jiggers. Progresso was overcrowded and poorly equipped, the sails were “old and weak” and she was too wide in the beam to be a good sailor.

The slave deck was 27 feet long, 21 feet 6 inches wide and 3 feet 6 inches high; when the rear hatch was closed in heavy weather the only ventilation was a single grating on the foredeck. The slavers would normally cram 500 slaves into this space but had rejected some of the proffered cargo at Quelimane as looking too weak to travel.

To put this in perspective; the two decks of a London Routemaster bus has about the same floor space as Progresso‘s slave-deck’s but the deck’s ceiling height would only allow a four-year-old male child to stand upright, the enslaved men and women had no room to lie down and could only sit.

The slaver had taken ten days to load at Quelimane so some of the slaves had been sitting in this cramped and airless space for nearly two weeks by the time she was captured. In April temperatures there rose to 30o C with 82% humidity.

The voyage south is the stuff of nightmares; on the first night under the Royal Navy’s command fifty-four slaves died of suffocation or were crushed when forced below by a storm. They continued to die from illness and their wounds throughout the voyage that was undertaken in atrocious weather with heavy seas and unfavourable winds in an overloaded and aging ship .

Six days out Hill describes their second storm:

“Last night I was awakened by the sound of taking in sails, amid peals of thunder, and lightnings the most vivid which I have anywhere witnessed. Flash succeeded flash with scarcely sensible intermission, blue, red, and of a still more dazzling white, which made the ye shrink, lighting up every object on deck as clearly as at midday. All the winds of heaven seemed let loose, as it blew alternately from every point of the compass.

The screams of distress from the sick and weak in the hold, mingled with the roar of the tempest. In the morning a strong gale came on, driving us back to the north.” 21

After three weeks the temperature began to fall and the naked slaves shivered in misery; another gale hit them on May 3rd and another on May 9th. At noon on the 11th they were hove-to under the worst gale they had seen with waves “towering high above us …. threatening to ingulf us every moment”.

On May 20th they had a favourable breeze for the first time in many days and they managed to sail at three or four knots but they only just made the same point south they had reached ten days previously. By the 24th they were becalmed.

Thomas Whitcombe

On June 1st 1843 they finally entered Table Bay, fifty days after leaving Quelimane. Of the 397 slaves on board, 50 having been taken off by Cleopatra, 175 22 had died. All the British crew had been ill with dysentery at different times and at least one, the boatswain’s mate had died.

Progresso‘s Portuguese and Spanish crew were set free to return to Rio de Janeiro.

Cleopatra had returned to her station off Quelimane where she was joined by H.M. Brig Bittern before the Progresso had even reached the Cape. The little squadron was later expanded by H.M.S. Sappho whose crew included our old friend the Reverend Hill.

In December of 1844 Cleopatra observed a slave brig being run aground and with the crew departing for shore in small boats. The ship was starting to break up in the surf and the sailors found 400 slaves onboard with the hatches nailed shut. There were too many slaves to take on board Cleopatra so all but seven were allowed to make their own way ashore before the slaver was set on fire.

The Young Lieutenant

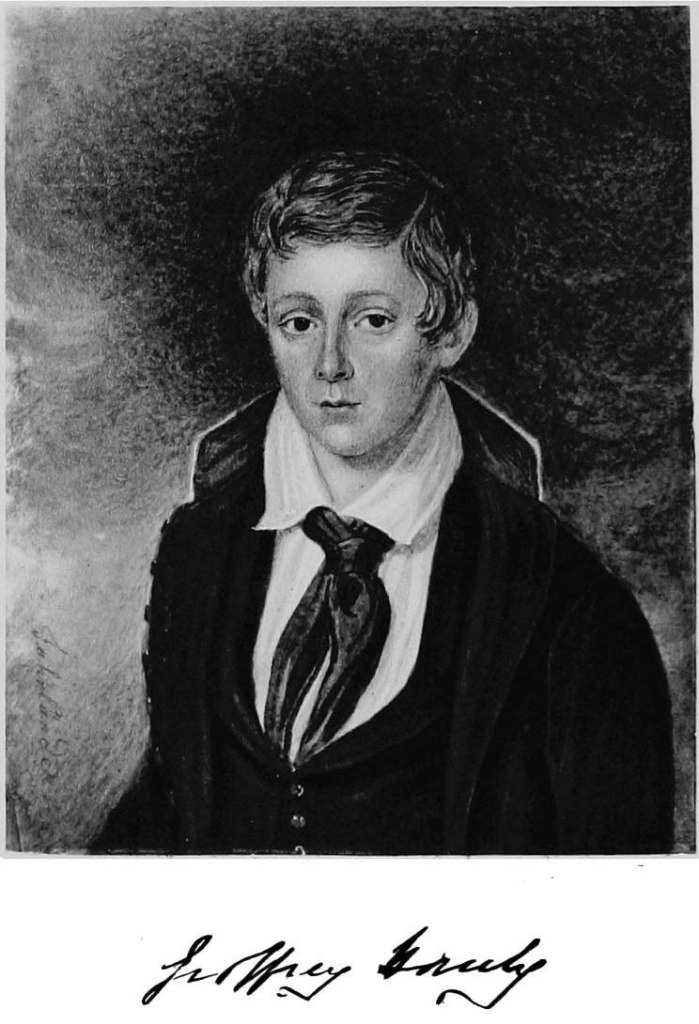

Hidden in the journals and biographies of various sailors there are snippets of information about the early years chasing slavers on the east coast. Geoffrey Phipps Hornby joined Cleopatra as a nineteen-year-old lieutenant at Simon’s Bay in the Autumn of 1844.

“She was a Symondite 26-gun frigate, and a very pretty little ship indeed, commanded by a very smart officer, Captain Wyvill, and for the next two years was employed exclusively in suppressing the slave-trade on the East Coast.” 23

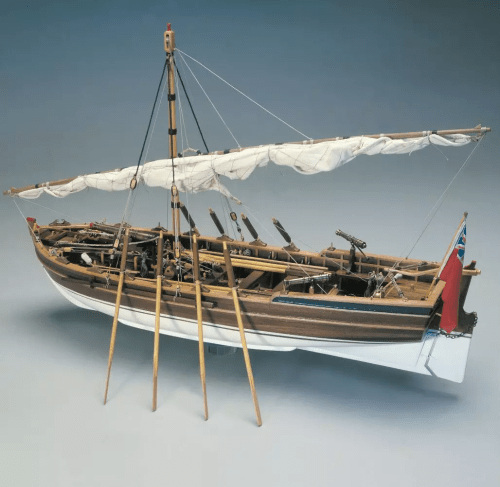

Hornby (pictured here as a midshipman) was a competent small boat sailor and was often placed in charge of Cleopatra’s boats when they went inshore hunting for slavers.

These boats were large enough to hold fourteen men plus provisions for several days, including live poultry and goats.

At night the boats were covered with awnings that were laced to the sides to protect the crew from malaria; fourteen men, livestock and the heat and humidity of a tropical coast must have made for interesting nights.

(Right: An armed pinnace from around 1800) 24

During his time with the Cleopatra Hornby remembered some “very exciting chases”; one slaver struck a reef when trying to escape and the Cleopatras were only able to take-off the women and children slaves leaving the men to swim for the shore; one left carrying a dutch cheese under each arm with another strapped to his back.

“The crew of five men either could not swim or else were afraid to face the surf, and as Captain Wyvill would not let his men’s lives be risked in saving such blackguards, they were left for the night; and though it was momentarily expected that the ship would go to pieces, no one felt very much compunction at their punishment, for those who had seen what cruelties were practised on the slaves grew very hard-hearted towards their capturers.” 25

After two years of slave chasing Lieutenant Hornby was sent down to Cape Town in command of a prize and from there he was posted home. 26

The Captain

Christopher Wyvill and Cleopatra stayed on station at the Cape and patrolling the Mozambique channel from 1842 until 1847 when she returned to England with her crew suffering badly from an outbreak of dysentery. Wyvill had been her captain since 31st December 1840 and had commanded her on the west Indies station prior to being assigned to the Cape.

Some sources suggest that the early African east coast squadron was unsuccessful but, whilst it is hard to measure success, it feels as if Wyvill and his mixed bag of ships had an impact on the Portuguese coast slave trade.

I have tracked down the names of fifteen slavers taken by the squadron and there is mention of at least four or five unnamed ships. Many of the ships were fitted for slaving with no slaves on board but at least 1,000 slaves were freed from Progresso and one other ship. 27

Looking at the three examples where we know the number of slaves on board their capacity ranged from 400 to 500. If this early squadron only intercepted and impounded 20 ships they had reduced the slavers’ capacity by 8,000 to 10,000 slaves per season.

In August of 1844 HMS Helena under command of Cornwallis Rickets in company with HMS Bittern took a suspected Portuguese slave ship, the Inião, in the Quelimane River. There were only six Africans on board, of whom five told the British sailors they had been taken against their will, but the master of the Inião argued they had been purchased and subsequently manumitted on condition that they served on board his ship as crew.

Helena, Bittern and Inião sailed to the Cape and, as was the norm, handed the Inião over to the British–Portuguese Court of Mixed Commission for adjudication. In the complicated court hearing that followed the judges, one British and one Portuguese, came to the conclusion that the status of the Africans on Inião was ambiguous and that the ship was not a slaver. She was restored to her master and the six Africans were given the option of sailing with her or staying in Cape Town as free men, only two stayed. The captors were charged with £2,430 costs, a staggering sum given a ship’s captain was paid around £360 a year at the time. 28

From The Victorian Royal Navy Website29

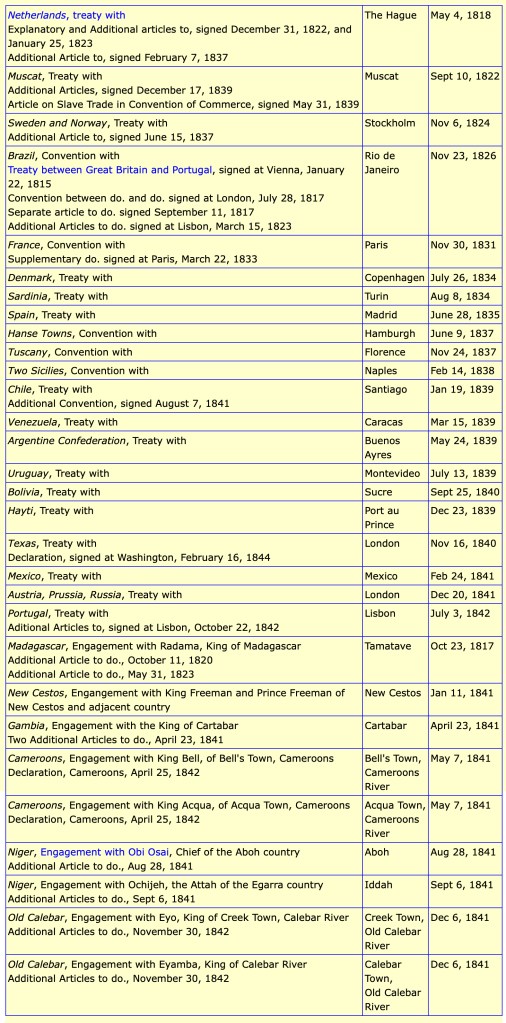

The case of the Inião highlights the challenge that faced the Royal Navy captains. They alone had to judge whether a ship was a slaver and, as in the case of the Inião, also had to second guess how the court of adjudication would interpret the evidence. To make his decision in 1844 he had to understand and interpret thirty different international treaties and agreements (see above) 30 and adhere to lengthy, complicated and, at times, contradictory Admiralty Instructions running to over 10,000 words. If he was right he and his crew shared, potentially substantial prize money; if an adjudicating court ruled against him he could face bankruptcy.

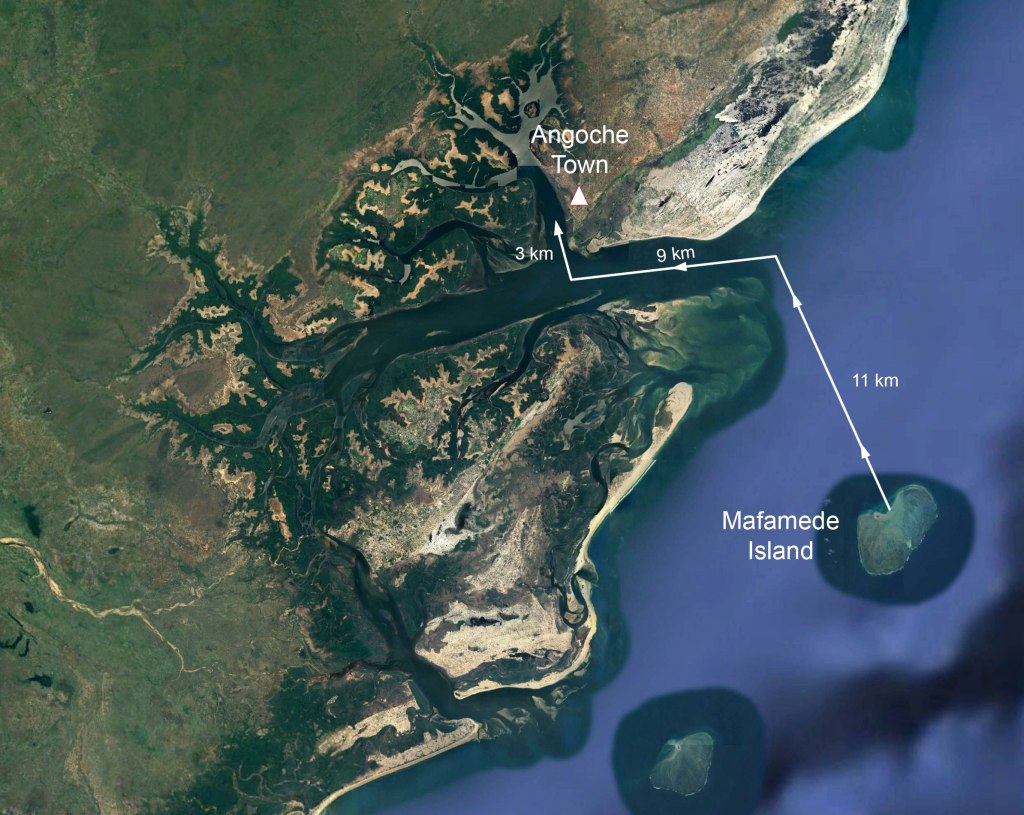

In 1846 the Lucy Penninam arrived, along with the Kentucky at Angoche, an Arab port between Quelimane and Mozambique Island. Cleopatra entered the Angoche River and burnt the two American slave ships. Unfortunately she missed three others who had loaded, slaves and already left for the Americas.

However, this action initiated a series of events that led to a change in the rules of engagement: the Portuguese became nervous that the Royal Navy were becoming too powerful on the east coast and could bypass them to make treaties with the many local chiefs, self-proclaimed sultans and others controlling ports north of Quelimane.

The Portuguese revoked previous agreements that allowed the British to enter her ports on the Mozambique coast and sent a mission to Angoche to bring the sultan to heal. The Portuguese ship Villa Flor arrived at Angoche and appeared to have successfully negotiated with the sultan but a large number of people whose livelihoods depended on the slave trade were not in agreement and attacked the Portuguese delegation killing three.

On discovering that slave ships were still using Angoche, Rear-Admiral Richard Dacres who was then the Commodore on the Cape of Good Hope Station offered his support to the Portuguese; and, as a result, an Anglo-Portuguese expedition supported by HMS Eurydice and HMS President set off in November 1847 to convince the sultan to acknowledge the authority of Portugal and ban slaving in his sultanate. Boats from Eurydice and President supported Portuguese troops led by Major Campos to storm the stockade at Angoche. 31

Midshipman George Sulivan who was not invoved in the 1847 action but who arrived on tne caost in ’49 wrote that the combined force was “repulsed with heavy losses” 32 but other sources reported a victory after a long day of fighting. The Sultan signed Señor Campos’ treaty promising to suppress the slave trade and report any slaving activities that came to his attention.33 As later events will show, this was a meaningless gesture.

Dhow Chasing

In 1849 Christopher Wyvill was appointed to H.M.S. Castor and instructed to “hoist his pennant” as Commodore of the Cape of Good Hope Station.

Commodore Wyvill arrived at the Cape in August of 1849 on board Castor which was now his flagship.

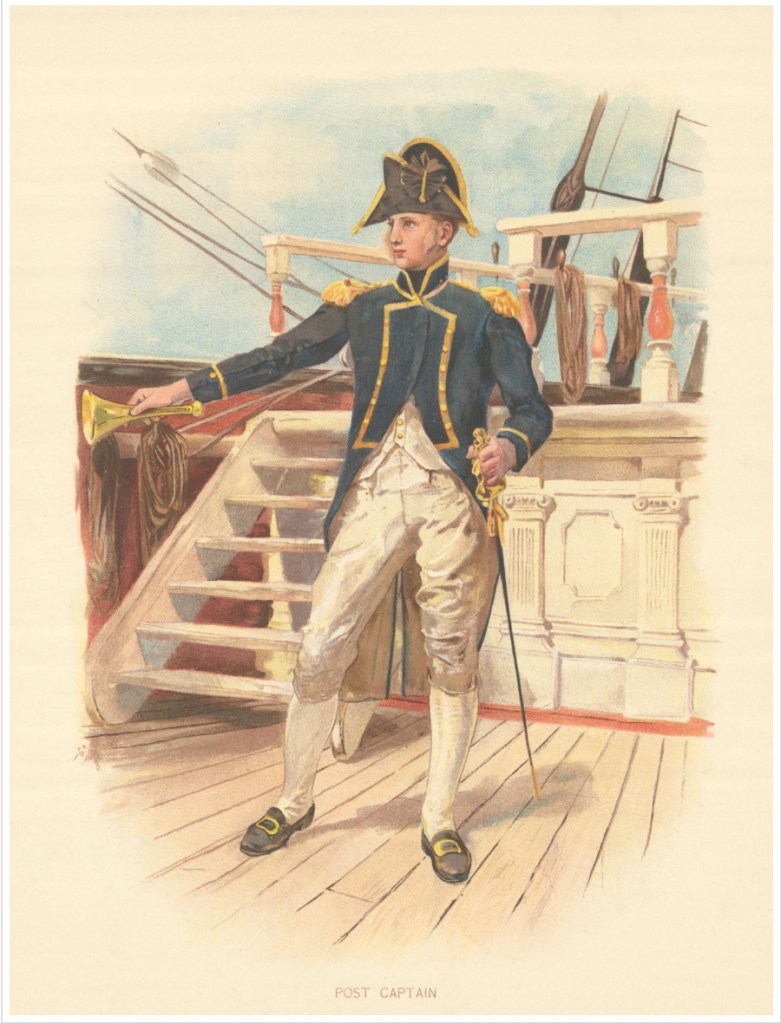

(A commodore of the 1840s stands with a Mate with a 2nd Class Boy in the background)

H.M.S. Dee was also at Simon’s Town and, because Castor was detained by a “convict dispute”,34 it was Dee that headed north to the Mozambique Channel in October with Castor‘s boats, including Wyvill’s private barge, on her deck.

Dee is an interesting ship; up to now all the Royal Navy’s warships in the Mozambique Channel had been from the age of sail but Dee was the Navy’s first warship that was a paddle steamer. 35

Reliable records of this early period on the East Coast are few and far between so we are reliant on the few first hand reports of sailors who served there.

George Lydiard Sulivan, a 17 year-old midshipman, was detached from Castor and on board Dee as she left the Cape on October 1st 1849 for a two week voyage to Madagascar where she was to take on water before patrolling the Mozambique Channel.

Sulivan, who return later to the east African coast as a Captain, wrote an account in 1873 of his experiences chasing dhows in the Indian Ocean. 36 Twenty three years after he had first served on an anti-slavery patrol he remained deeply concerned that:

“…despite the “sincere profession of the Portuguese Government to abolish it,…. it is still going on, though in a far more subtle way, to as great an extent as ever, and with greater cruelties than any practised by the Arabs.”

In ’49 the East Coast was still busy with slavers; Portuguese, Spanish and Americans in the south, Arabs in the North. The Europeans and Americans often disguised their ships as whalers to avoid the British patrols and when they thought the coast was clear anchored off river mouths where slaves could be ferried out. They loaded as quickly as possible and sailed south to round the Cape of Good Hope to head to the Americas.

In November Dee was off the River Angoche. Lieutenant Crowder, who was in temporary command of Dee, mounted an expedition to look for slavers at the stockaded Arab town up river. He commanded a sizeable force in five ships’ boats loaded with three lieutenants, two master’s mates, two midshipmen, a ship’s surgeon and around 70 men.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

The flotilla would have been a sight to see, Castor’s pinnace (see left for an example) and Captain Wyvill’s personal barge led by Dee’s two paddlebox steamers and her cutter.

They sailed into the mouth of the river but some of the boats ran aground on a sandbank and after waiting for the tide to lift them they off anchored, covered the boats with their tent-like awnings, served an extra ration of rum laced with quinine and settled down for the night, keeping their spirits high by each boats’ crew taking it in turns to sing.

The next morning the little flotilla worked its way up the Angoche River on the incoming tide until they were level with the kilometre-wide creek where the town lay. The slave barracoons at Angoche were usually full waiting for buyers but Crowder’s force could not risk a land assault knowing that when the British were last there they reported 2,000 armed men and six canon defending the settlement and the fort.

Spherical case shot was a Similar concept but instead of a cartridge shaped shell it was a round shot filled with shrapnel and an explosive charge.

They were hunting slave ships and to their delight as they turned into the creek at one o’clock in the afternoon they spotted their prey, a large dhow of about 100 tons, hauled close in under the guns of the fort. The tide was still rising and helped them sail on up the creek towards the fort accompanied by the sound of drums being beaten on the shore. At four o’clock they were within 200 yards of the fort and in range of its guns, and the flotilla was swept with round shot and grape seriously injuring two sailors but not slowing their approach.

The final approach speaks to the courage of these men, the tide was still rising but the water was so shallow they kept running aground, they formed a line abreast under a constant barrage of grape, canister and shot from the fort. They were soon close enough to return fire and Midshipman Sulivan’s boat fired “spherical case-shots” which exploded above the stockade clearing the defenders in fifteen minutes and forcing them to take cover in nearby woodland.

The dhow’s Arab crew were firing muskets at the approaching sailors but one of Dee’s paddlebox steamers cleared her decks with canister and grape.

At about five o’clock Dyer, a master’s mate, slipped over the side of Dee’s other paddlebox steamer and swam in under the stern of the dhow from where he was able to board her and start a fire. The flotilla was still under fire but it was now coming from the Arabs hiding in the forested shoreline whose musketry was accurate enough to severely wound another two sailors. At five-thirty the tide began to turn and with the dhow on fire and the fort silenced the flotilla withdrew. Several men had been seriously wounded, one with his ribs caved in by grape shot, but all eventually recovered.

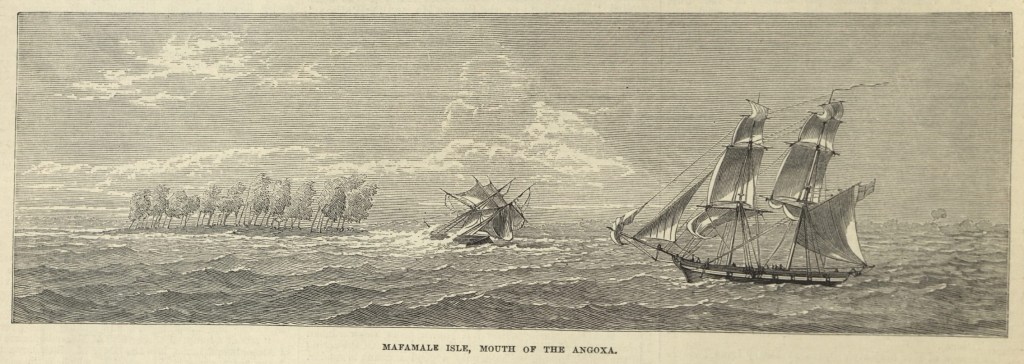

After the success at Angoche Dee left a detachment of men with Castor‘s pinnace and barge on Mafamale Island about 11 km off the mouth of the Angoche River. It was decribed as:

“About three quarters of a mile long, covered with casuarina trees and thin grass, and surrounded by a coral reef, it was an ideal rendezvous with a good channel and anchorage.” 37

To detach a small force of this kind was not unusual and allowed a sngle ship to be in two places at once, the men at Mafamale could blockade Angoche where they knew the slave barracoons were still full and Dee could patrol elsewhere on the coast. They were based here for several months, occasionally provisioned by Dee or HMS Pantaloon which was also now on the east coast.

HMS Pantaloon

Nicholas Condy, Government Art Collection

Pantaloon had been on the West Coast for many years and was famous for taking the Spanish slave ship Barboleta off Lagos in 1845, following a two day chase and ferocious hand-to-hand fighting with the Pantaloon’s boarding party. She must have also been successful in eastern waters; while the Castor‘s were camped on Mafamale, because Campbell, one of Pantaloon’s lieutenants, was ordered away to take a prize to the Cape.

The New York Public Library Digital Collections38

Sulivan recalls this ship as The Philanthropy with 400 slaves on board which must have been taken by Pantaloon in February 1850. He later writes, when lamenting Castor‘s bad luck in finding slavers that:

“The Pantaloon and Orestes, were more fortunate, however, having taken two or three American or Spanish ships, one or two of which were full of slaves.” 39

Castor, her energetic Commodore, Christopher Wyvill along with Midshipman George Sulivan and a sick list of 113 men, which is about half the crew, eventually left the Mozambique Channel and sailed for the Cape. She arrived at Cape Town on 5th February 1851, sixteen months after starting her patrol.

John Julian

Castor remained at Simon’s Town as Wyvill’s flagship until at least September 1851 before sailing back to her old hunting grounds possibly captained by Commander Bunce. She took four slave dhows between November 1851 and August 1852 before returning to the Cape and the onto Chatham to be paid off.

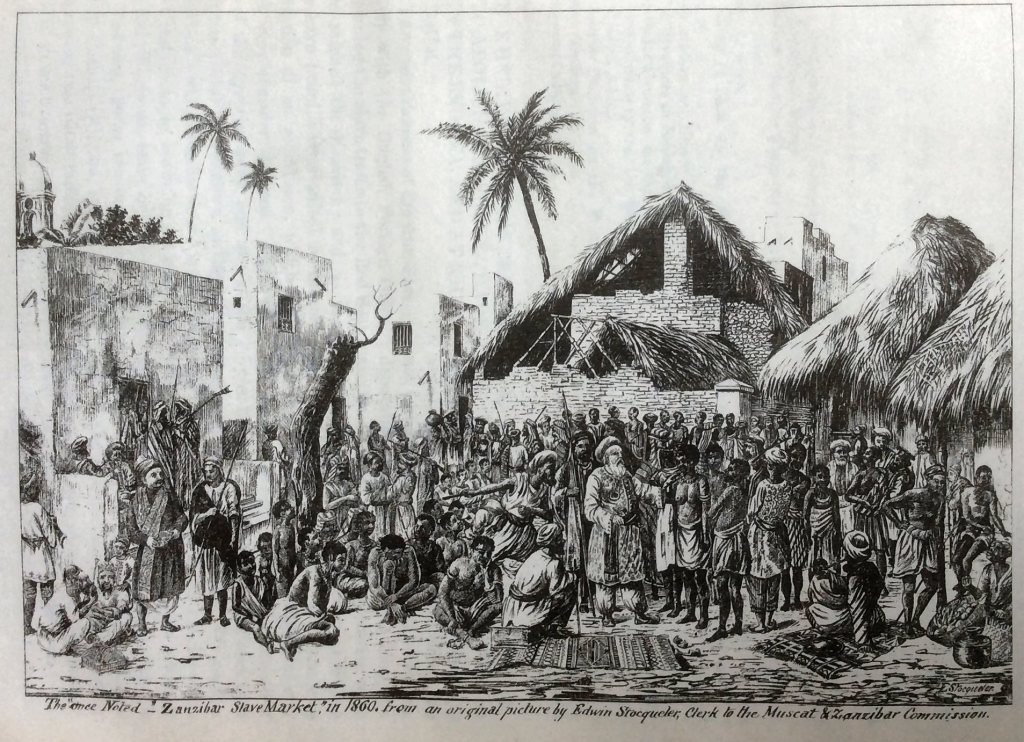

Zanzibar 1850

In way of closing the story of the first half of the nineteenth century it is worth looking at Castor‘s visit to Zanzibar soon after collecting Midshipman Sulivan and his colleagues from Mafamale Island. Anchoring in Zanzibar harbour and touring the town in 1850 frustrated and angered many British naval officers and must have led them to question whether they were achieving anything tacking up and down this dangerous coast.

In 1850 the Sultanate of Zanzibar was a coastal strip running from Cape Delgado in the south to Mogadishu and Brava in the north including the islands of Zanzibar, Pemba and Mafia. Sayyid Said Ibn Sultan, who was also the Sultan of Oman had been instrumental in creating this commercial empire built on three products: ivory, slaves and cloves.

Zanzibar needed slaves to work on its clove plantations, as domestic servants for the wealthy Arab and Indian merchants who lived in the town and to stock the slave market which in turn supplied Arabia, India, Ceylon and the plantations on the French islands of Mauritius and Reunion.

At the beginning of the nineteenth-century around 40,000 African people were being sold as slaves in the market at Zanzibar every year. By the 1860’s the clove plantations on Zanzibar and Pemba alone needed twelve thousand additional slaves annually and a further seven thousand to produce oleaginous seeds on the coast of Kenya and Somalia; 40 the market may have been handling as many as 70,000 slaves a year.

Many British officers would have visited the market to see young African children being sold for a few pounds and women being purchased from pimps and then returned after a few days by men avoiding strict laws against prostitution.

Right: Bishop Edward Steere, the bishop of the Universities Mission to Central Africa

Steere visiting in the 1860’s described his first impressions:

“The greater number of houses are built only of mud and stud, thatched with the cocoanut leaf. They are divided by internal partitions into a number of small rooms, but have no light except from the door ; as for smoke, it finds its way through the thatch promiscuously. There are some chief thoroughfares, and some streets of shops, which are merely small stone houses with the front of the bottom story taken out, and are therefore quite open to the street…….

I hope one may never see again such sights as one used to see almost daily when we first landed in Zanzibar — the miserable remains of the great slave caravans from the interior, brought by sea to Zanzibar, packed so closely that they could scarcely move, and allowed nothing of food on the voyage but a few handfuls of raw rice passed round to be nibbled at…..

……the parties of slaves that were led from the custom-house to their owners’ houses presented every form of emaciation and disease…….. There were even some [slaves] who were left lying at the custom-house, because it was doubted whether they would recover at all, and the traders would not pay the duties till they knew. Beyond even this, we have found some yet alive, left upon the beach by the sea, into which they had been thrown as the dhow neared the harbour, because they were already past all hope of recovery. 41

Officers and men of the Royal Navy stopping here to provision as Castor did in 1850 were confronted with a slave state, a town where ten to fifteen thousand slaves were employed in plain sight by American, European and Indian merchants using Yemeni or Comorian contractors as intermediaries to circumvent their own countries’ laws prohibiting slave ownership.

José Navarro y Llorens – Artvee

Although it was out of sight to a visiting European rich Arabs had many concubines; when Sultan Said died he left seventy five enslaved concubines 42 and thirty-six children who had been born to slave mothers.

The idea that the children of concubines were born free in the eyes of the law is often cited as part of a justification for slavery in the Arab world. Realistically the law and practice were not always the same thing. Many concubines were kept for a very short time, a few weeks or months and a pregnant concubine could easily be forced to marry a slave so her child was born into slavery. 43 There is no escaping the fact that concubinage in any society is the sale and purhase of sex slaves.

Zanzibar harbour became very crowded when the south-west monsoon that brought the dhows south faded and the north-east monsoon had not yet reached sufficient strength to carry them home. Dhows would arrive daily from the Swahili Coast loaded with slaves to anchor in Zanzibar harbour in plain sight of the British cruisers, until in Sulivan’s words:

“……..they surrounded the English flag carried by our cruisers who cannot touch them”

These were legal slave traders allowed, under the Sultan’s treaty with Britain, to only trade and transport slaves within his east African territories; 44 so, as long as the slavers paid tax in the customs house they would be provided with a licence from the Sultan to transport however many slaves they had on board to another port in the Sultanate.

The slavers would leave Zanzibar with a license to carry slaves to Lomu Island towards the northern limit of Zanzibar’s territories but would just kept sailing north to the slave markets of Arabia and the Persian Gulf.

British sailors could watch the slave dhows departing northwards for the Red Sea, Arabia, the Persian Gulf and India with no way of stopping them. This trade continued unmolested until the innovative Commodore Leopold Heath arrived in Bombay in 1867 as Commander-in-Chief East Indies Station and disrupted the status-quo.

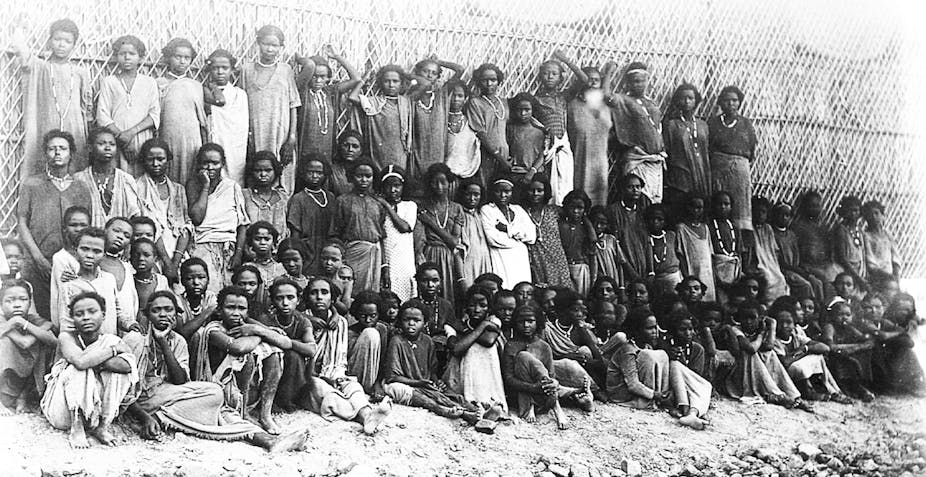

Liberated Slaves and Apprentices

Britain’s objective was to end the slave trade; legislation, diplomacy, treaties and the efforts of the Royal Navy generally reflected this goal and much has been written on all of these subjects. However, rather less thought has been given to the Africans found on board slave ships by the Royal Navy.

Before the British Abolition Act of 1807 slaves found onboard an enemy or pirate ship were treated as cargo and auctioned off along with any other cargo on board. After the act came into force in 1808 it became illegal to return any captured slave to slavery so on being found on a slave ship they became the property of the British crown.

Prize money 45 was paid for each slave captured in these circumstances. The rates and rules associated with these payments varied during the nineteenth century.

The Navy would take the captured slaves to the nearest court of adjudication, which for the Mozimbique Channel in the 1840’s and 1850’s, was Cape Town, where the status of the slave ship and the captured slaves could be considered. If the court “condemned” the ship and its human cargo the sailors could look forward to receiving their reward but for the captured slaves the act stated that:

“the Negroes that shall be taken and condemned as forfeited to the Crown under the Acts of Parliament passed for the Abolition of the Slave Trade” were to be “apprenticed” so that they might “acquire such a degree of practical instruction from the masters to whom they were assigned, as would enable them at a future period to support themselves.” 46

In reality, in the Cape Colony, where most of the “freed” slaves from the Mozambique Channel were taken, this apprenticeship was seen as a much needed source of labour. Over two thousand slaves were indentured as apprentices at the Cape in the first eight years of the 1807 Act. These “prize negroes” as they were called joined an existing slave population at the Cape as it was not until 1834 that owning slaves became illegal in British colonies and even then slaves emancipated under this Act were compelled to work an apprenticeship for four years.

The “prize negro” system was badly abused and there were instances where apprentices were sold again as slaves, many were treated no better than slaves, few received the “instruction” that the law required their masters to provide and the status of prize negroes’ children was poorly defined.

(The photo on the left is of liberated slaves on St, Helena in 1900) 47

The “prize negroes” sunk to the lowest level of society, below the Cape born slaves who were often skilled craftsmen. In the minds of the colonists they were free, unskilled labourers who had no monetary value, other than to be hired out as labourers to other colonists. There were a number of court cases in the 1840’s that highlighted the abusive treatment meted out to the emancipated slaves by farmers. 48

At the end of their apprenticeship the law required an official to call the freed slave and his master together and to tell him that he was:

“….at liberty to engage himself upon the most advantageous terms he can either with the Master with whom he is at present serving or with some other.”

But, he was also warned that vagrancy could not be tolerated and, if he did not find work he would be forcibly placed into appropriate employment.

By the time Cleopatra was patrolling the Mozambique Channel the fact Royal Navy could stop and search Portuguese slavers brought about a surge in the number of captured slaves being delivered to Cape Town. For example, the Escorpao taken by HMS Modeste in 1839 landed seven hundred and nine captive Africans.

This was the first of many large captures and in the 1840’s twenty one slave ships were condemned by the Vice-Admiralty Court in Cape Town. In that decade alone at least three thousand “prize negro” liberated slaves arrived in Cape Town from the east coast patrols and another seventeen hundred were shipped from St Helena where they had been landed by the West Coast or South Atlantic patrols.

C.D.Bell c.1840

The British government were more than aware that the colonists were abusing the system to the detriment of the freed slaves and slowly began to make changes. In 1843 new laws stopped children under the age of ten being apprenticed without their parents consent and males under the age of twenty-one could only be indentured as household servants or in trades where they would learn a skill. Older slaves could only be indentured as farm labourers for one year.

Despite several reforms the system remained imperfect and liberated slaves even after being released from their apprenticeships or at the expiry of their indentures did not become land-owning, free citizens. They were at the lowest level of society, there was little difference between slavery and freedom.

1808 to 1853 Conclusion

Given the scale of the trade, the limited number of Royal Navy cruisers on patrol at any one time and their focus on the Mozambique Channel, it is probably fair to say that the Cape Squadron had little hope of having a significant limited impact on the African east coast slave-trade.

Certainly the Arab and Swahili trade north of Mozambique Island seems to have carried on regardless. The navy at Bombay in British India was responsible for the Arabian Sea and George Sulivan lamented that the Indian Navy49 “never made any captures” of slavers, in fact he had heard them say that on seeing a slave dhow they would put the helm the other way50.

However, it should not be forgotten that the bravery and self sacrifice of these Victorian sailors did lead to the capture of many slave ships and thousands of enslaved African’s were emancipated.

When researching the subject of slavery it is all too easy to focus on the statistics and to lose sight of the fact the African people who reached the Cape or St Helena had already survived a horrific journey. They might have been captured or purchased for a few metres of cloth deep in central Africa, in the Congo Basin, the valleys of the Luangwa or Shire rivers or in the fertile plains west of Lake Malawi. They had been taken from their homes, separated from family bonds, their culture and often their language.

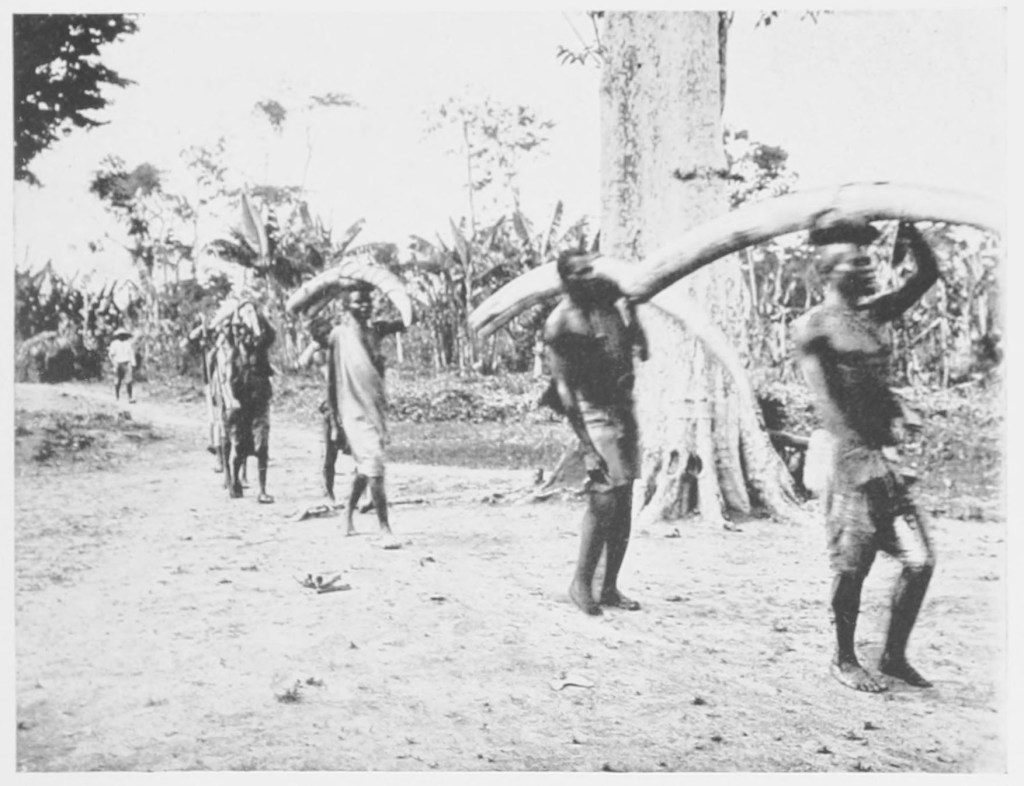

They had been marched for weeks or months to reach one of the inland trading centres such as Kota Kota on the shores of Lake Malawi or Ujiji in modern day Tanzania where they would be crowded into barracoons or slave pens until the trader had a viable number for onward passage to the coast.

To reach this point they would have already seen many of their number die from the deprivations of the march, disease or from wounds inflicted by the slavers; people unable to keep up would have been left to die or were beaten to death and dumped.

The strong relationship between ivory and slave trading meant many slaves would have carried a huge elephant tusk weighing up to 100 kgs. Males were often yoked together with forked branches, women and chidren of both sexes were raped by the slavers, babies were seen as unnecessary baggage and torn from their mothers’ arms before being murdered.

Fred Moir the manager of the African Lakes Company was witness to passing slave caravans:

“….in addition to their heavy weight of grain or ivory, [women] carried little brown babies, dear to their hearts …… The double burden was almost too much, and still they struggled wearily on, knowing too well that when they showed signs of fatigue, not the slaver’s ivory, but the living child would be torn from them and thrown aside to die.” 51

From Lake Malawi to Kilwa or another of the Swahili ports could take another three or four months of walking where they were either caged in slave barracoons to await European traders or crammed in dhows to make the crossing to Zanzibar.

Arab slavers told their captives that Europeans wanted them as food so even being “rescued” by the Royal Navy would have been a traumatic experience. As described by Reverend Hill the long cruise from the Mozambique Channel to Cape Town would have been terrifying for experienced sailors let alone emaciated people who had never seen the ocean let alone a storm at sea and, of course, many slaves died at sea.

Eventually a small fraction of the original number of people who set out from central Africa arrived at the Cape. A South African journalist witnessed one such arrival:

“Set down upon our shores naked and, no interpreter having yet been found, speechless. A more helpless set of creatures, or more deserving of our sympathies, cannot be imagined. A large proportion of them are children, under ten years of age! We do not know where they came from.” 52

“We do not know where they came from” sums up the tragedy of the emancipated slave. In the nineteenth century few slaves came from anywhere near the east African coast, they came from central Africa where only a handful of Europeans had even visited; there was never any chance of them being repatriated.

Being let free on the coast would have probably led to their recapture by slavers; being taken to Cape Town meant fourteen years as an unpaid labourer working for a colonist.

There were no happy endings for enslaved African people in the war against slavery on the east coast of Africa.

Footnotes

- Or so we are told. Interestingly there is a letter in the National Archives at Kew from Edward Henry Columbine dated 19th August 1808 saying: “In consequence of the appointment of a commission to survey the Coast of Africa, of which he is a member. Requests the following instruments. [List of equipment includes Sextants, Telescope, Theodolite, thermometer, Compasses etc]. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12797932 ↩︎

- Captain Columbine is engaged in communication with the Admiralty requesting equipment for the squadron and various matters concerning his crew and supplies in August and September 1808 and he asks for approval to buy a small tender for the Solebay on the 23rd October 1808. It is clear that Soleway isn’t in perfect condition when Soleway takes command on 6th September as Admiral Otway “agrees that the ship needs to be brought into harbour for a refit”. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12797936 ↩︎

- 4th July 1809 ↩︎

- I assume the squadron left Portsmouth after 23rd October 1808 (his last communication with the Admiralty), but HMS Solebay is back at Spithead on 1st January 1809 January. On April 6th 1809 Captain Columbine is in Westminster where he receives his final instructions from Lord Castlereagh, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies regarding his mission to the coast of Africa and we know they were back in Sierra Leone by early July 1809. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12798283 ↩︎

- The force comprised 120 seamen and 50 Royal Marines in HMS Solebay, Derwent, Tigris (a brig), George (a colonial schooner) plus 6 other armed schooners and sloops and a umber of unarmed vessels and 166 officers and men under the command of Major Charles William Maxwell in the troop ship Agincourt. During the assault HMS Solway was lost along with Captain Parker of the Derwent. the French surrendered and based on naval despatches in the National Archive it appears the Columbine became the de facto Governor of Senegal. https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_battle&id=853 ↩︎

- https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12799006 ↩︎

- Mariana 20th April 1810, Esperanza 24th April 1810 ↩︎

- Not the luckiest ship, Thomas Ludlum a former Governor of Sierra Leone died on board Crocodile 25th July 1810. Ludlum was one of the earliest people to take action against the slave trade by arresting the American slave ship Triton on 19th November 1807. ↩︎

- Gerald S. Graham (1967) Great Britain in the Indian Ocean: A Study of Maritime Enterprise 1810-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press https://archive.org/details/greatbritaininin0000grah/page/n7/mode/2up?q=slave ↩︎

- In 1842 Lord Broughton gave a speech in the house of lords pointing out that British capital was still financing the slave-trade. “I am here to denounce those over whom our power is complete, ……… nor do I think it will be necessary to detain you long, while I show, that by the stimulus of British speculation, with the accession of British agents, through the employment of British capital, the foreign slave-traffic is in great part perpetrated and protected. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1842/aug/02/slave-trade ↩︎

- Gerald S. Graham (1967) Great Britain in the Indian Ocean: A Study of Maritime Enterprise 1810-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press https://archive.org/details/greatbritaininin0000grah/page/n7/mode/2up?q=slave ↩︎

- Christopher Sanders (1985) Liberated Africans in Cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Graham 1967 ↩︎

- Anglo-Portuguese Treaty 1810 as published by Amazon Kindle ↩︎

- Jake Christopher Richards (2018) Anti-Slave-Trade Law, ‘Liberated Africans’ and the State in the South Atlantic World, C.1839–1852 https://academic.oup.com/past/article/241/1/179/5134187# ↩︎

- Pascoe Grenfell Hill was born in Marazion, Cornwall in 1804. He was educated at Mill Hill School Middlesex and Trinity College Dublin where he graduated in 1836. He was ordained that same year and joined the Royal Navy as a Chaplain. He served until 1845. After leaving the navy he remained a clergyman and wrote several books including those referred to here. He died in 1882. ↩︎

- In April 1842 H.M.S. Cleopatra under the command of Captain Christopher Wyvill was ordered to proceed to the Cape of Good Hope Station with instructions to convey Lieutenant General Sir William Gomm to Mauritius where he was to assume the role of Governor. Cleopatra left Spithead in July of 1842 and arrived at Rio de Janeiro on 6th September. After a stay of one week she set sail for the Cape arriving there on 9th October. At the end of December she proceeded to Mauritius. ↩︎

- Rev. Pascoe Grenfell Hill (1844) Fifty Days on Board a Slave Vessel in the Mozambique Channel in April & May 1843. New York: J, Winchester, New World Press https://ia801307.us.archive.org/34/items/fiftydaysonboard1844hill/fiftydaysonboard1844hill.pdf ↩︎

- The Rev. Hill breaks this down as 189 men mostly under 20 years of age, 45 women and 213 boys. Initially they estimate that 25 are ill but this proves to be an underestimate. ↩︎

- Francesca Aton (2023) Archaeologists Discover Wreckage of Notorious Slave Ship off Brazil https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/archaeologists-discover-wreckage-of-notorious-slave-ship-off-brazil-1234674088/ ↩︎

- Rev. Pascoe Grenfell Hill ↩︎

- 163 slaves had died by the time they docked on June 1st. Another 6 died the next day and when Hill visits them on shore on the 19th he records that 175 had died on board Progresso and 1 on Cleopatra. ↩︎

- Mrs Fred Egerton (1896) Admiral of the Fleet Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby. London: William Blackwood and Sons https://archive.org/details/cu31924027922479/mode/2up ↩︎

- According to one source a Royal Navy frigate would carry a 22 ft longboat, a 28 ft pinnace and a 22 ft yawl. https://modelshipworld.com/topic/1677-question-what-boats-would-an-18th-c-frigate-have-carried/ ↩︎

- Mrs Fred Egerton ↩︎

- Sir Geoffrey Thomas Phipps Hornby 1825 to 1895 served in the Royal navy from 1837 to 1895. He had a second tour of duty as a slave chaser as Commander-in-Chief, West Africa Squadron in 1865. He became an Admiral of the Fleet in 1888 before retiring in 1895 and dying of influenza soon after.

http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Geoffrey_Thomas_Phipps_Hornby ↩︎ - Between them they took several slavers: Defensivo, Marco, Isabel, Opio Feliz, Attrevida, Silveira, Anna, Avila, Zacette de Marco, Kentucky, Lucy Penniman, Constante, Improviso and the Imperador Don Pedro Segundo as well as several unnamed vessels. These ships were fitted for slaving with most having no slaves on board. Progresso and one other unnamed vessel had, between them 900 slaves on board. ↩︎

- Jake Christopher Richards (2018) Anti-Slave-Trade Law, ‘Liberated Africans’ and the State in the South Atlantic World, C.1839–1852 https://academic.oup.com/past/article/241/1/179/5134187 ↩︎

- The Victorian Royal Navy https://www.pdavis.nl/Slave_1.htm ↩︎

- Instructions for the Suppression of the Slave Trade 1844 https://www.pdavis.nl/Slave_1.htm ↩︎

- M. D. D. Newitt (1972) Angoche, the Slave Trade and the Portuguese c. 1844-1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/180760?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle. ↩︎

- M. D. D. Newitt (1972) Angoche, the Slave Trade and the Portuguese c. 1844-1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/180760?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- In 1847 the British government was reforming the penal system and one of those reforms was to send convicts nearing the end of their sentences to the colonies as labourers and to serve out their time. Once their sentence was served they could either stay in the colony or return to England. The Secretary of State for the Colonies, Earl Grey, thought that the Cape Colony would be pleased to receive some extra labour and asked its governor to sound out local opinion. The white population of Cape Town was vehemently opposed and a petition was drawn up and signed by 450 people demanding that Lord Grey sent his convicts elsewhere. However, Grey had not waited to hear from the Cape and H.M.S. Neptune was despatched from Bermuda with 300 convicts on board. When she arrived at the Cape in September 1849 the colony was in an uproar. Rallies were being held and treats of violence were made if any convicts were landed. In February 1950 the Neptune and her convicts left the Cape and headed for Australia. https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=20328 ↩︎

- Dee was ordered along with Rhadamanthus, Salamander, and Phoenix and all four entered service in 1832, Dee was 166ft long with two side-paddles that could propel her at a maximum speed of 8 knots. At the time she was at the Cape Station she probably had 6 x 32 pdr guns on pivot mounts and a 10″ shell gun. ↩︎

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle. ↩︎

- Peter Collister (1980) The Sulivans and the Slave Trade. London: Rex Collings ↩︎

- New York Public Library Digital Collections https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-4050-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 ↩︎

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle. ↩︎

- Abdul Sheriff (2020) History of Zanzibar to 1890 https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-669;jsessionid=D881611AFF2D499D9843D15C7E47AFF1?rskey=MblqfH ↩︎

- Rev. R.M.Heanley (1888) A Memoir of Edward Steere D.D. L.L.D. thord Missionary Bishop in Central Africa. London: George Bell & Sons ↩︎

- Abdul Sheriff (2014) Suria: Concubine or Secondary Slave Wife?

The Case of Zanzibar in the Nineteenth Century – Published in Sex, Power and Slavery edited by Gwen Campbell and Elizabeth Elbourne (2014) Athens: Ohio University Press https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/52811/1/external_content.pdf ↩︎ - Matthew S Hopper (2014) Slavery, Family Life, and the African Diaspora in the Arabian Gulf Published in Sex, Power and Slavery edited by Gwen Campbell and Elizabeth Elbourne (2014) Athens: Ohio University Press https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/52811/1/external_content.pdf ↩︎

- Under the Moresby Treaty of 1822 Sayyid Sa’id agreed to ban the sale of slaves to Christians and to limit the trade by forbidding Zanzibari ships sailing south of Cape Delago or cross an arbitrary line to the east. In 1839 the prohibited area was increased and in 1845 slave trade between Zanzibar and Oman was prohibited. ↩︎

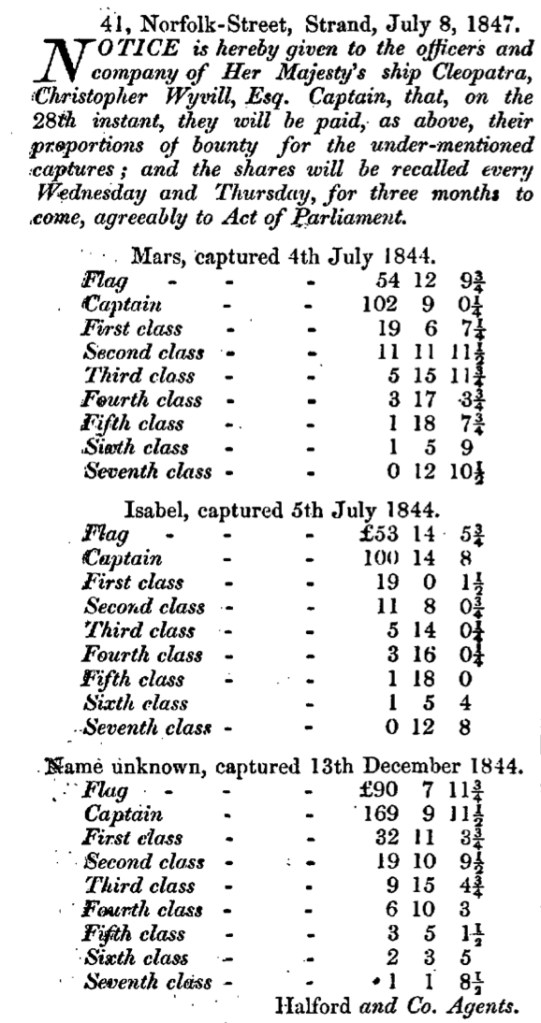

- To understand the process by which slaves were freed we first need to look at the system of prize money that rewarded Royal Navy officers and crews for destroying or capturing the warships and merchantmen belonging to Britain’s enemies.

When a British ship captured an enemy ship it was taken into a British controlled port where a court of adjudication determined whether it was legal prize and, if so, established its value, including any cargo. Enemy ships legitimately destroyed also attracted prize money.

This “prize money” was distributed to the officers and crew based on their rank.

Prize money was particularly rewarding for sailors serving on frigates and other smaller ships as they were often the chasers who hunted down and captured merchantmen.

The award of prize money was announced in the London Gazette and, as can be seen in the example of three prizes taken by Cleopatra under the command of Captain Wyvill in 1843, the amounts varied significantly depending on rank. Wyvill earned around £375 from these three prizes at a time when he was probably earning £30 a month. Flag officers commanding squadrons or fleets also received a cut. ↩︎ - Christopher Saunders (1985) Liberated Africans in cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?seq=1 ↩︎

- Many enslaved people liberated in the South Atlantic were taken to and left at St Helena. Between 1840 and the late 1860’s 27,000 liberated slaves were deposited on St Helena. Many were relocated but nearly 10,000 remained on the island. ↩︎

- Joline Young (2019) Liberated Slaves? https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/liberated-slaves-joline-young ↩︎

- I’m not sure who he means as there is Her Majesty’s Indian Marine which is, in effect the Indian Navy, and the East Indies Station which is very much Royal Navy. Based on Leopold Heath’s frustrations in the 1860’s Sullivan probably means both. ↩︎

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle. ↩︎

- Fred L.M. Moir (1923) After Livingstone: An African Trade Romance. London: Hodder and Stoughton https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.507079/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater&q=slaves ↩︎

- Joline Young (2019) Liberated Slaves? https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/liberated-slaves-joline-young ↩︎

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.