- The Return of the Black Explorer

- James Chuma After 1875

- Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA)

- A Walk to Nyasaland

- A Short Trip to Magila

- Founding the Freed Slave Settlement at Masasi

- Chauncy Maples and the Masasi Settlement

- East Central African Expedition

- The Temple Phipson-Wybrants Expedition 1880

- Joseph Thomson and the Rovuma Valley 1881

- A Short but Stirring Life

- Footnotes

- Other Sources and Further Reading

The Return of the Black Explorer

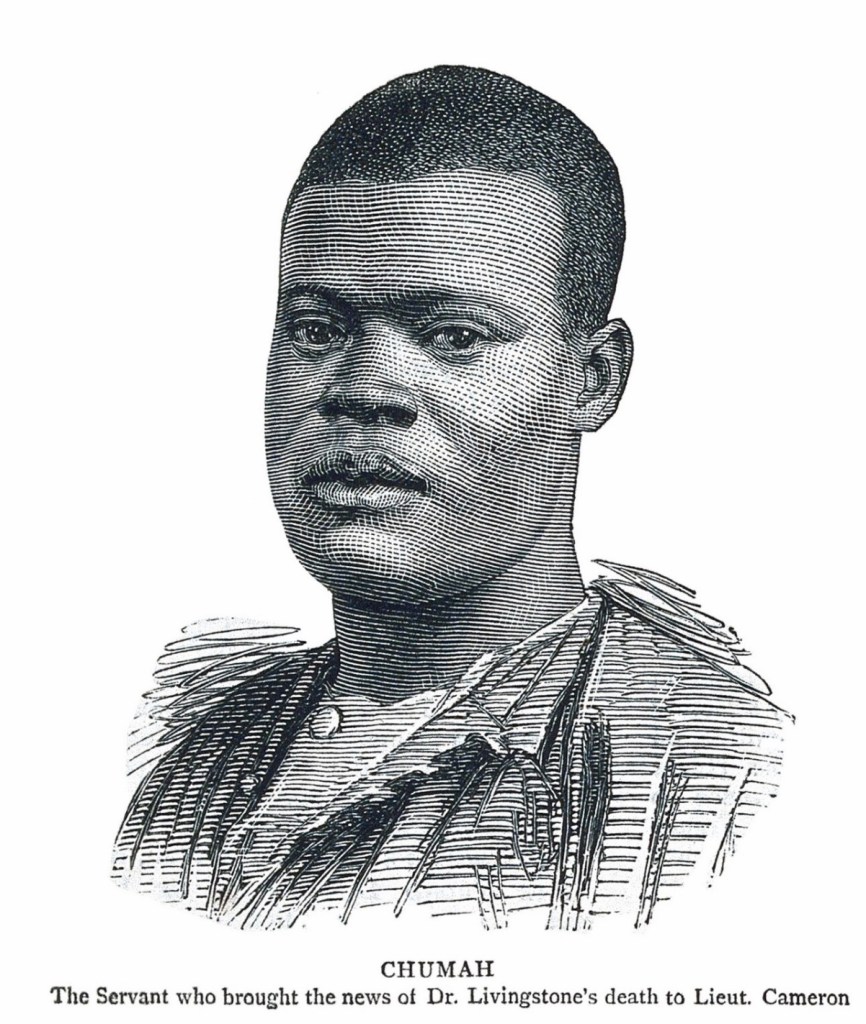

James Chuma was the most famous of the liberated slaves whose early life at the Magomero mission and contribution to Livingstone’s last expedition 1865-74, is described in a previous article (here).

After returning to Zanzibar with the Scottish explorer’s body he wrote to Horace Waller:

“Chumah gives compliments to Mr. Waller. I have been all over with Dr. Livingstone in Africa, and am now in Zanzibar with my wife. I am now by myself. I do not know what work to do.

Give compliments to my sister, who is at the Cape. His name Chaika. I hear it with Dr. Livingstone that letters came to him that Kinsolo, my brother, been shot with a gun. I don’t know who shoot him. If please you get answer, send to me at Zanzibar.

Susi, Kibanga man, give him compliments to Mr. Waller and to Dr. Livingstone’s son, and now he is in Zanzibar and will wait for a letter. If you have got any business in Africa, let us know. We want to go in Africaagain where Dr. Livingstone died. “

“Susi don’t know write.” 1

The letter was handed to Captain Brine of HMS Briton by Chuma and Susi and forwarded to England. On 4th April 1874 Horace Waller sent a copy of the letter to the London Times where it was published on 10th April. Chaika (Chasika) and Kinsolo (Chinsoro) appear to be liberated slaves from Magomero; in his letter to the Times Wallace explains that Chinsoro was brutally murdered sometime ago and his widow Chasika “is very poorly off at the Cape”.

The letter confirms that he and N’taéka were still married; she had joined Chuma and Livingstone at Unyanyembe (Tabora) in 1872 and had been persuaded to marry Chuma as Livingstone was worried that her beauty might cause problems amongst his few remaining followers if she remained unattached.

On the left are Agnes and Thomas Livingstone who were two of David Livingstone’s six children. The group are surrounded by Livingstone’s maps and papers that were carried to the coast with his body by Susi, Chuma and others. 2

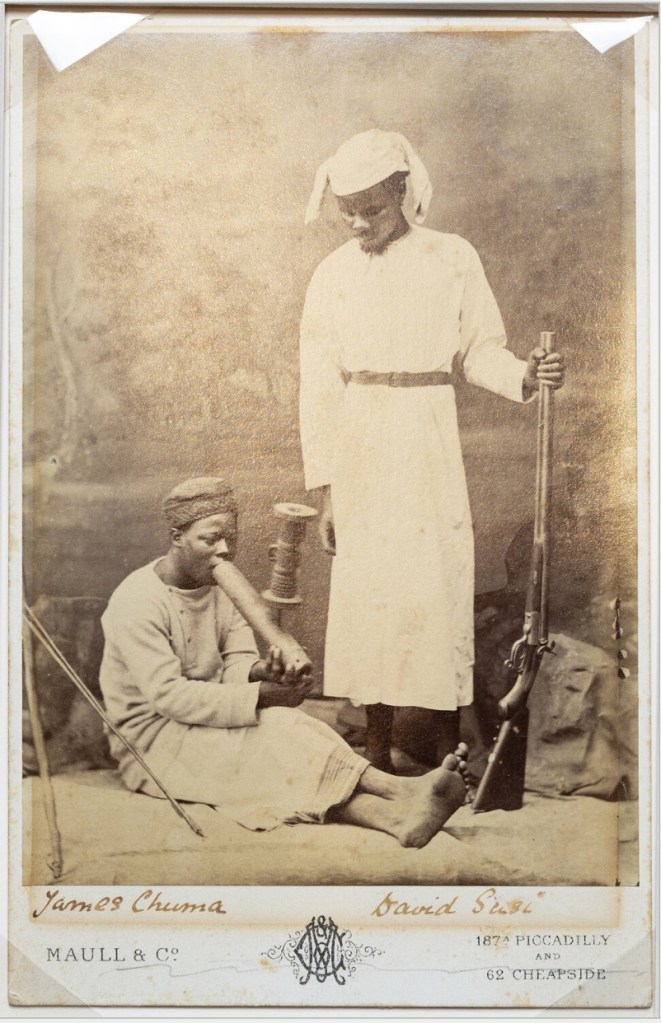

It appears that the likely sequence of events was that on receiving the above letter in early April Wallace immediately sent funds to allow Chuma and Susi to board ship for England. They attended the Royal Geographical Society in June where they are awarded their medals for accompanying Livingstone. While in England the two Africans helped Wallace interpret Livingstone’s papers to enable him to write his two volumes of The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa.

They were back in Zanzibar by October and James Chuma is mentioned in the history 3 of the Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) as the man “to whom that was owing that the doctor’s body was brought down to the coast” and recorded as joining the mission in Zanzibar in 1874. It seems a reasonable assumption that Wallace arranged for him to be offered that employment.

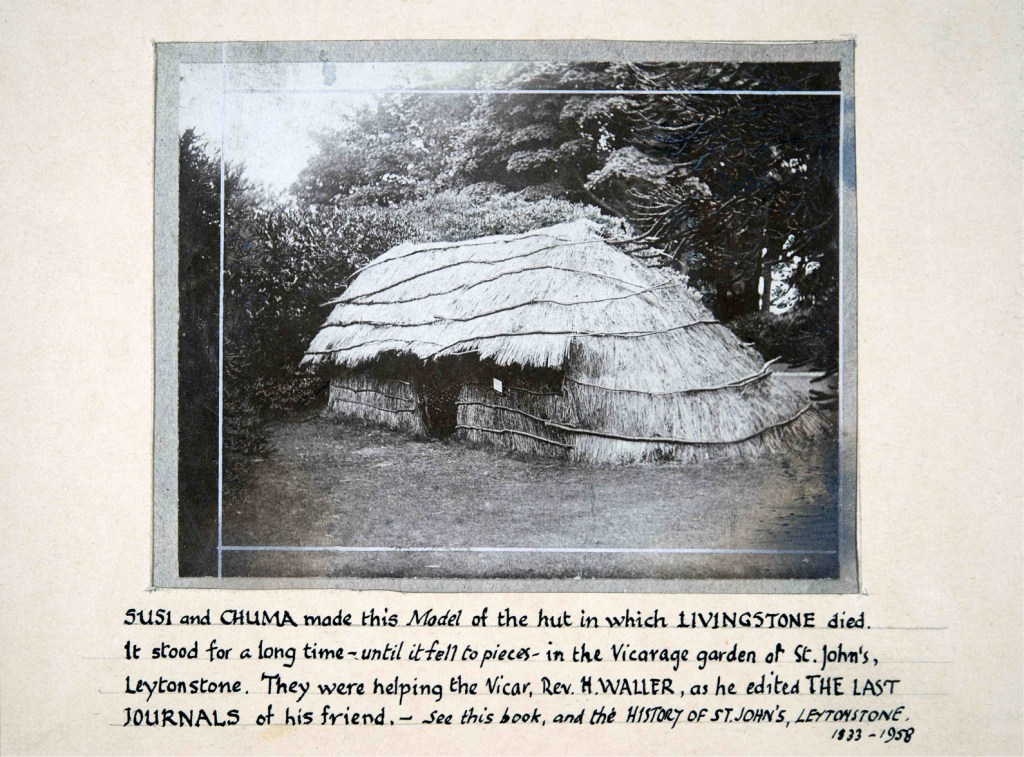

Chuma and Susi were each paid £5 by the Royal Geographical Society for helping Waller. they stayed at the vicarage in Leytonstone, became members of the church choir and attended the National school 4 in the old chapel.

They built two replicas of the hut in which Livingstone had died, one in the garden at Leytonstone and the other in the Scottish Highlands for Anna Mary Livingstone, the doctor’s youngest daughter. 5

James Chuma After 1875

Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA)

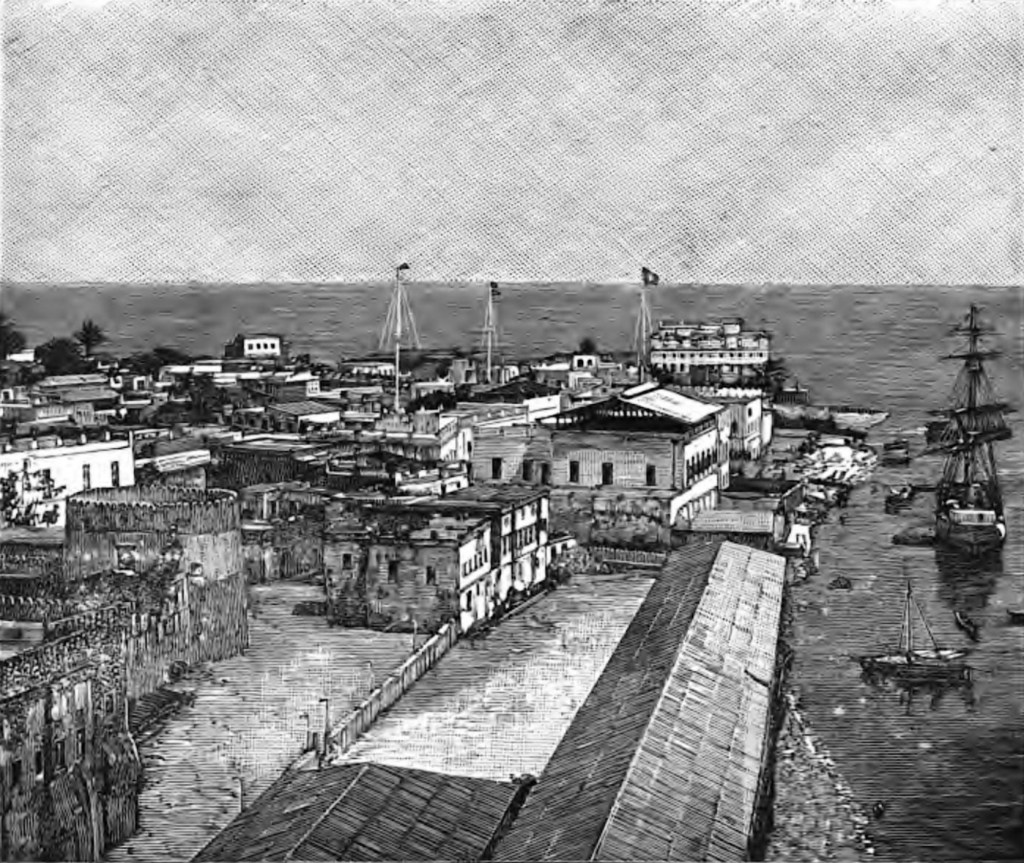

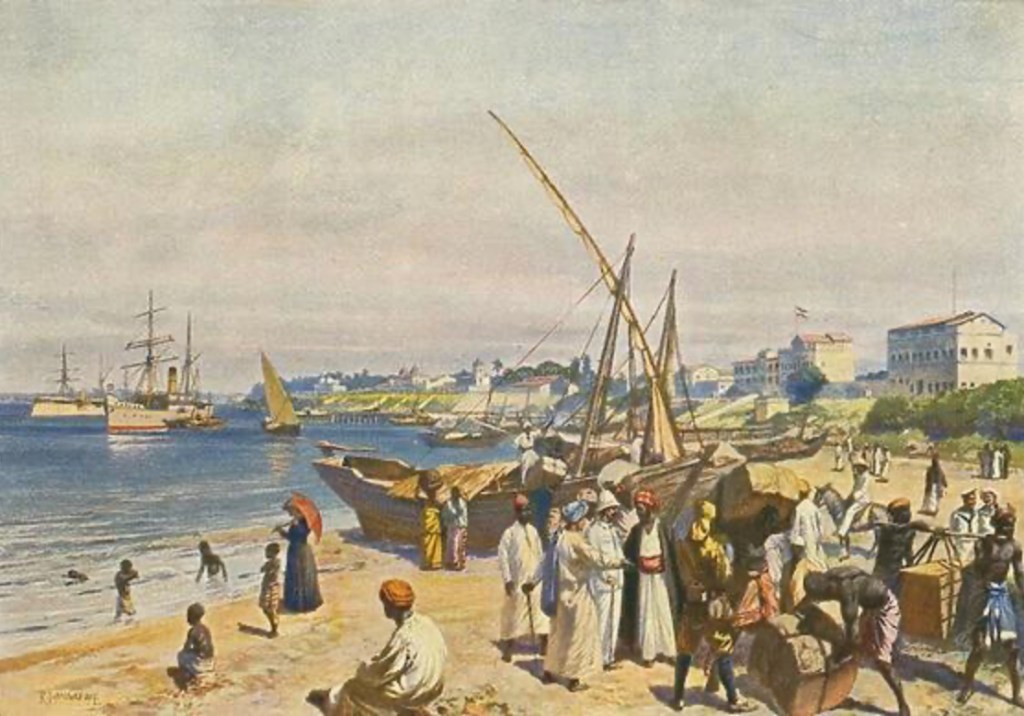

When he returned to Zanzibar in 1875 he would have found a very different city to the one he had left with Livingstone’s last expedition in 1865. On 8th June 1873 an order signed by Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar had been posted at the customs house:

To allow our subjects who may see this and also to others, may God save you, know tat we have prohibited the transport of raw slaves by sea in all of our harbours and have closed the markets which are for the sale of slaves through all our dominions. Whosever therefore shall ship a raw slave after this date will render himself liable to punishment and this he will bring upon himself. Be this known. 7

Edward Steere (left), the third of the UMCA bishops in central Africa, acquired the land upon which the slave market had operated.

Initially he built a hut from where he and his missionaries started to preach and on Christmas Day 1873 the first stone was laid of Christ Church, the Anglican cathedral, that stands today in Stone Town.

Steere believed that it was important that the mission took its missionary work back into central Africa and when making a speech in Oxford in 1874 said:

“Bishop Mackenzie’s grave is some three hundred miles inland, and he only touched the coast region. Beyond and beyond lie nation after nation … How are these nations ever to hear the good news that we have to tell them? … We propose to send up first a small party of a few men of good judgement, to make acquaintance with the chiefs, and look through the country, to find the healthiest, most acceptable, and most central spot on which to make our chief settlement.” 9

Steere was a man who led from the front and on his return to Zanzibar to he began to plan his expedition into central Africa.

On 24th August 1875 the Zanzibar mission held a festival to celebrate St. Bartholomew’s day and the baptism of thirty-eight converts. James Chuma and Abdullah Susi were the guests of honour at the celebratory dinner and soon afterwards they left for central Africa.

A Walk to Nyasaland

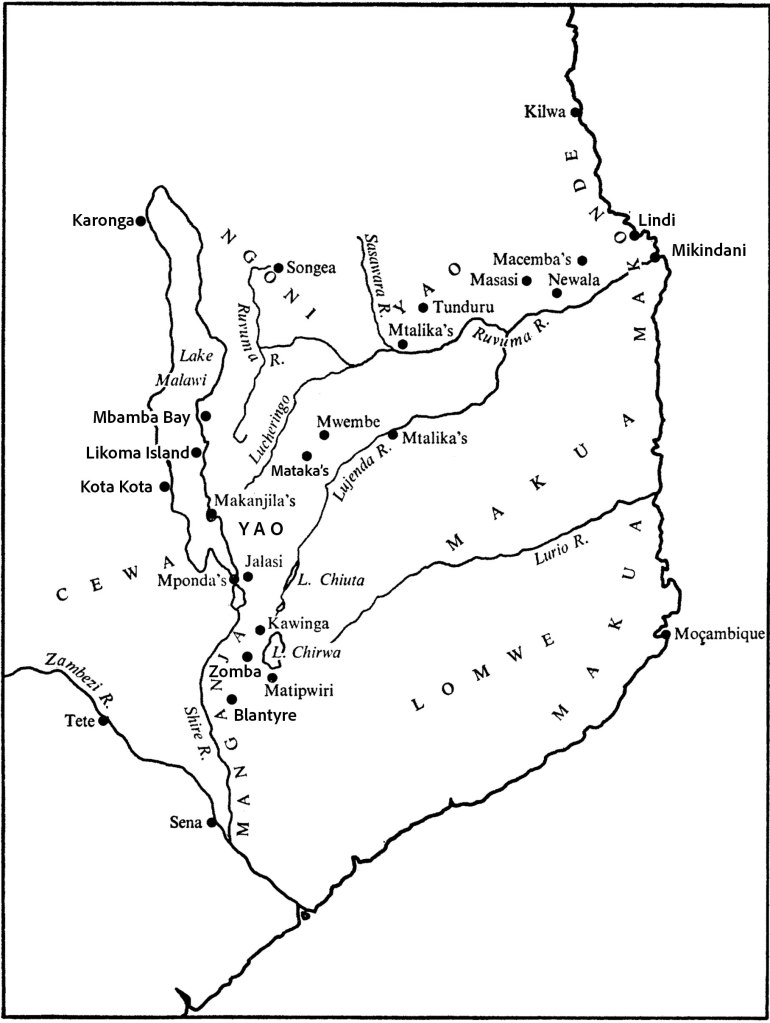

The Bishop’s expedition to Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) left Zanzibar in late August ’75 with Chuma and Susi in charge of “about twenty” porters.

They took the mail steamer to Lindi, in modern day Tanzania, and about 100 kilometres from Mikindani where Chuma and Susi had landed with Livingstone ten years earlier.

After endless delays including the illness and withdrawal of two of the Europeans, they left leave Lindi on 1st November, with forty porters.

….. Chuma as the “captain of the expedition”, and two coast men, said to have great experience as guides. These last turned out to be merely expensive ornaments but Chuma was throughout the soul of the expedition, and success without him would have been all but impossible.:

The bishop provides a description of, what he calls, the chaotic conditions that existed in the land between the coast and Lake Nyasa along the Rovuma (Ruvuma) and Lugenda Valleys . He knew that the land was once well populated but it had been ravaged by slavers; one of the first villages they pass through near the Rovuma River is inhabited by Gindo 11 people who are escaped slaves from Kilwa.

They pass through the country of the Makua people (right12) who still live in the Mtwara Region in southern Tanzania. Everywhere they went they were warned about aggressive raiders, saw abandoned villages, occasional escaped and often dead slaves and met displaced people.

They turned south from the Rovuma and crossed the Lukwisi River which Chuma mistakes for the Luatize which he recalled from his travels with Livingstone; the rains had started and the river was in spate.

“He [Chuma] immediately set to work, to make a “lie down” (ulalo). This is done by cutting a tree so as to fall across the river with its branches holding to the bottom, to keep it from being carried down stream.

If necessary another tree is cut down to fall from the opposite side and meet it. Then in carefully built ulalos, poles are tied to walk upon, and a bamboo handrail fixed, and so a very respectable bridge is formed.

Ours was only a rough affair, men stood on the branches of the tree and passed the loads across, and then I was carried over and so everything passed over dry.” 13

Their expedition showed that despite the Sultan prohibiting the slave trade from his ports the trade was still thriving inland, they met nine slave caravans and saw between 1,500 and 2,000 enslaved people being taken to the coast.

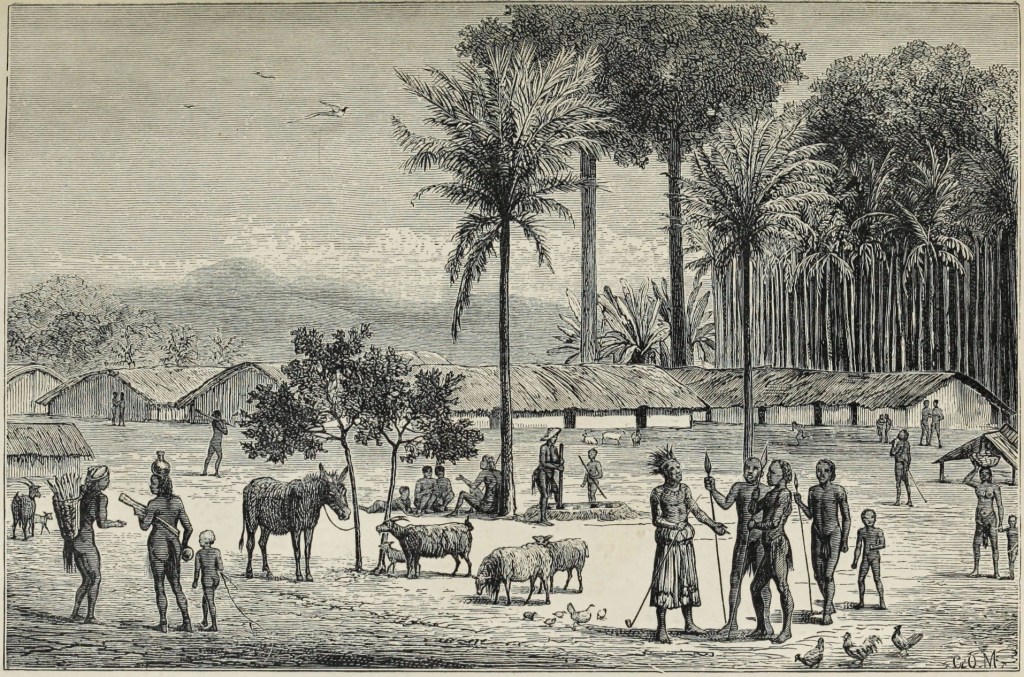

They reached the Yao Chief Mataka’s main village of Mwembe which is now the town of Mataca in Mozambique and about 300 kilometres from Lake Malawi, here, Chuma introduces the bishop to the delights of the local beer.

(See left for a 1896 photograph of a Yao.)

Mataka’s people are Yao and the bishop believed that they would become Christians or Moslems before long but the race would be won by whomever first learnt to write and read the Yao language.

Steere and his successors were to be disappointed as Islam fitted more comfortably with Yao traditions. Steere and Chuma had met Mataka Nyambi who was the Yao chief of a large territory centred on Mwembi. Mataka is alleged to have had 600 wives, each with their own hut, spread across eight villages with 200 of them living at Mwembi. Livingstone and Chuma had met Mataka in 1866 and at that time were told his territory stretched all the way to the lake. When he died he was buried along with thirty boys and thirty girls. 14

On December 22nd they turned for home and reached Lindi on 21st January 1876.

A Short Trip to Magila

In June 1876 Chuma, leading sixteen porters, accompanied Bishop Steere to Magila, the UMCA’s mission station that had been established in 1868 by the Reverend C.A Arlington and was the first mission on the mainland since their withdrawal from Magomero and the Shire Valley back in 1863.

In 1902 Gertrude Frere wrote an abbreviated history of the UMCA for children, she provided a sugar-coated description of Magila at the turn of the century:

“Magila, about sixty miles from Zanzibar, is a lovely spot situated below the Shamble Hills, which are covered with vegetation. through the plain runs a river with a rocky bed, and on these rocks the schoolboys now spread their clothes when they go down to bathe. now, too, there is a railway station near, reached through and avenue of orange trees so thick with fruit that even the school children cannot eat it all.” 15

Founding the Freed Slave Settlement at Masasi

In September 1876 Bishop Steere began planning another expedition to Nyasaland, 17 this time he intended to take a group of liberated slaves, who had probably originated from the Lake Nyasa area, from Mbweni 18 and establish a settlement for them near to Lake Nyasa.

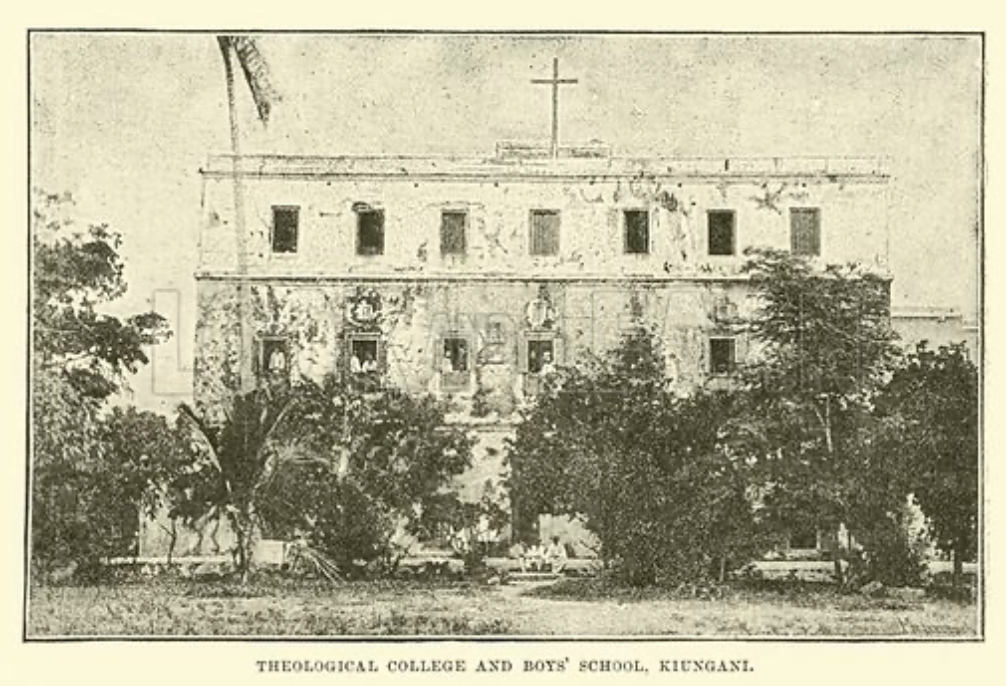

On October 6th he left Zanzibar for Lindi with two Europeans, Rev. W.P. Johnson and Mr. Beardall, four scholars from the UMCA Theological School at Kiungani in Kenya, seventy porters, thirty-one Mbweni men and twenty-four Mbweni women.

His caravan leader was, of course, James Chuma.

They reached the area of Masasi which lies around 150 kms from the coast where they found fertile soil with tamarind, cashew and banana growing wild. There was abundant iron ore which the local Makua people smelted in furnaces dug into termite mounds. (see right) 19

The liberated Mbweni slaves liked the location and asked to site the settlement there. The bishop agreed and stayed at Masasi for a month building a mission house, huts to accommodate the liberated slaves and planting fruit trees.

After his return to Zanzibar Chuma was sent on two further missions to Masasi.

Chauncy Maples and the Masasi Settlement

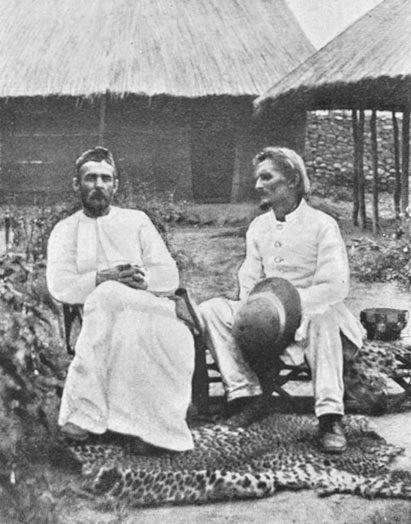

In July 1877 Chuma was again despatched for Masasi but this time he was leading a caravan for Chauncy Maples, a newly ordained priest and a natural organiser (on the left in the photo), who was to take charge of the mission. William Johnson (on right in the photo) was already there.

On this occasion Chuma led fifty porters, nine more freed slaves, six boys and another European, Joseph Williams.

According to his sister:

“Chauncy threw himself heart and soul into the work of establishing on a firm basis the first Christian village in Yao and Makua land, and in starting direct missionary work in the neighbourhood. He was a born pioneer and organizer, and here truly was pioneer work before him.

The Bishop had accomplished wonders in the short period, a few weeks only of his stay at Masasi. He had planned out the village. A broad road was made, with the native houses, built of bamboo and thatch, on each side; while ten feet of stone wall were already rising as a beginning of the church. This church was soon completed after Maples’ arrival.” 20

In 1877 and ’78 Chuma continued to build his reputation as a caravan leader making further journeys to the mainland as a trusted member of the UMCA mission in Zanzibar.

East Central African Expedition

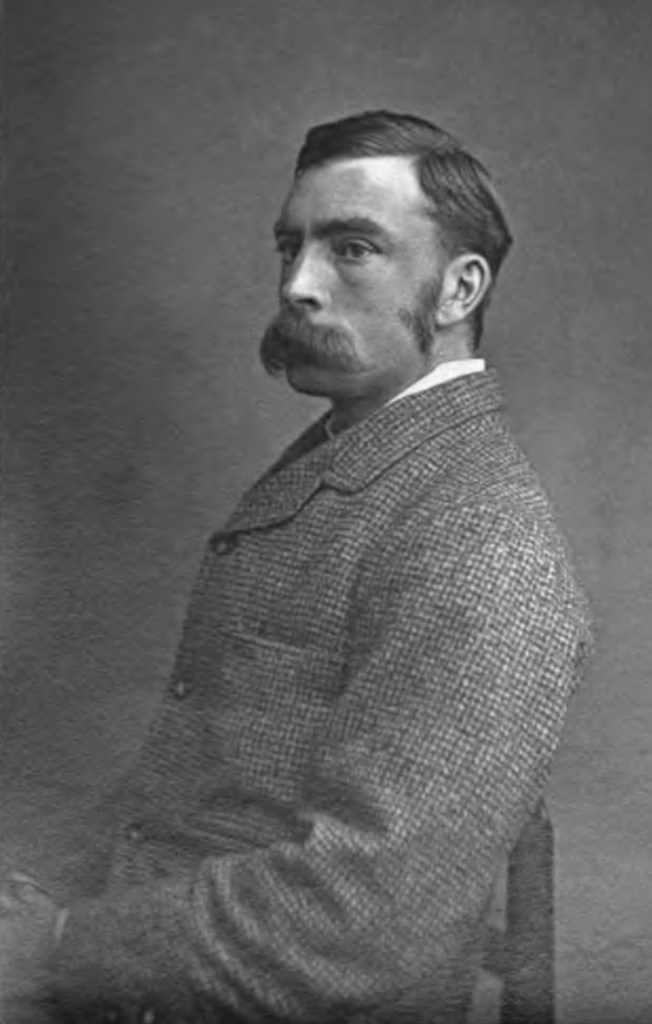

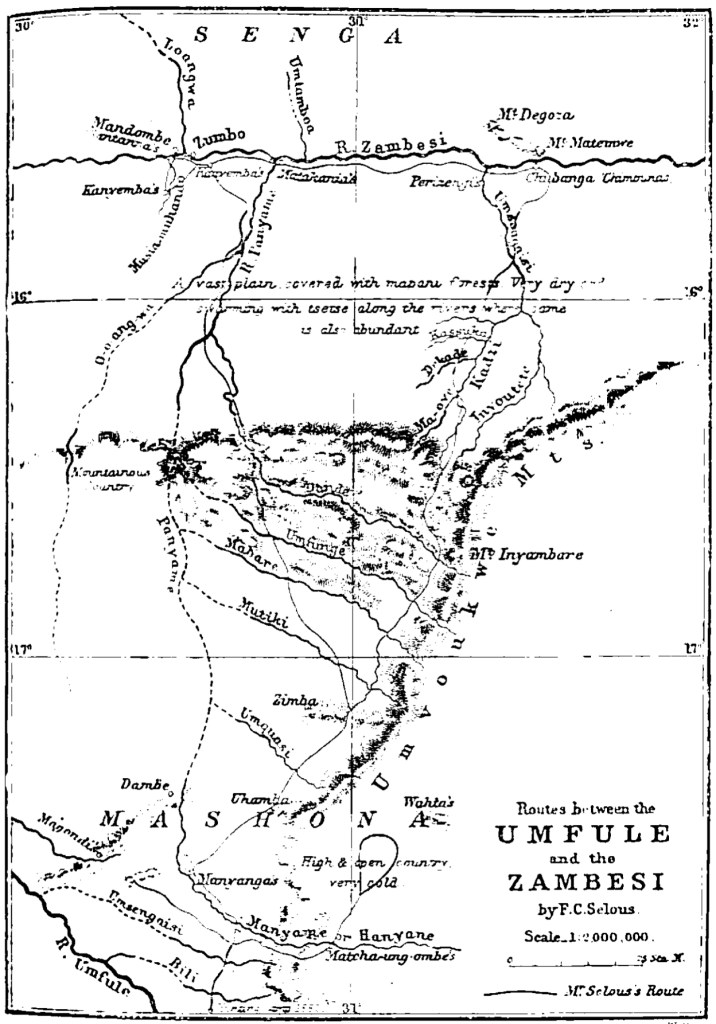

In 1876 Keith Johnston, a thirty-four year old geographer, (right) and Joseph Thomson, a twenty-year-old geologist, were appointed by the Royal Geographical Society to take an expedition to “unveil some of the mysteries which yet enshroud the Dark Continent.”

The aim was to explore the land between Dar-es-Salaam and Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) and then to continue to Lake Tanganyika. It went by the name of the East Central African Expedition.

The two men arrived in Zanzibar on 5th January 1879 to be met by the Consul-General Dr. John Kirk, his wife and four children. They soon set about preparing for their expedition.

“The formation of our caravan was, of course, a matter of all-absorbing interest to us. Our first important step in that direction was the engagement of Chuma as our chief headman.” 22

Thomson (right in a photograph taken in ca. 1879 after he had returned from Africa) was impressed by James Chuma recognising that his long service with Livingstone prepared him well for travelling with Europeans.

He praised his command of English and “about a dozen native dialects.”

Long gone is the frivolous, eleven-year-old boy rescued at Mbame’s in 1861, a boy so easily distracted as a fourteen-year-old that people could steal his master’s belongings from under his nose. Chuma is now around twenty-nine years-old and is widely travelled, not just in Africa, but schooled in Bombay and a visitor to England.

He is a very confident fellow and, as a caravan leader, very much in charge:

“Full of anecdote, and fun, and jollity, he was an immense favourite with the men, and yet he preserved such an authority over them that no one presumed to disobey his orders. If any one was rash enough to do so, woe betide the offender! Chuma went straight at him; and though not tall or muscular himself, he speedily humbled the strongest.”

Thomson is surprisingly self-aware for a Victorian explorer; he recognises he is ignorant about every aspect of their forthcoming travels and the success of the mission, especially in the first few months is in the hands of Chuma, the caravan leader or, as Thomson calls him, the native headman.

Having praised Chuma’s good humour, leadership skills and ability to command the caravan’s respect making him invaluable, Thomson describes some less attractive attributes.

Lies came natural to him, not indeed from any premeditated purpose, or from desire of gaining profit or pleasure to himself, but simply because they seemed to be always nearer his tongue than the truth.

(He) was also extremely fond of acting the big man, and right well he could do it. To keep up his dignity he deemed it necessary to be somewhat lavish in his expenditure, so that we required to be continually on the lookout, and to keep a firm hand upon him to check his extravagance.

Ottomar Heinrich Beta

With Chuma’s help the two Europeans recruited an expeditionary force of 128 men of whom thirty-eight were Yao and nineteen were from Nyasa (Malawi); when they reached Dar-es-Salaam on 15th May 1879 the numbers were made up to 150. The expedition was well equipped, Kirk, who had seen everyone from Speke to Stanley set off from Zanzibar, thought:

“No better organized caravan ever left the coast for the interior.”

They were also well armed with seventy guns ranging from flintlocks to thirty Snider carbines, twenty Enfields and two, high velocity, express rifles suitable for large game. All the equipment had to be divided into loads of between sixty to seventy pounds ( 27 to 31 kgs) before they were assigned to the porters.

“If we had been left to ourselves we would have been rather in a dilemma, but here Chuma was in his element.

He danced about with indignation, seizing this man by the ear and that by the throat, and dragging him to his appointed load, while he volleyed out his threats, or lashed them with his satire. He was ably seconded by the headmen, who, thoroughly enjoying the pleasures of command, seemed to glory in laying violent hauds upon mutinous porters.

In an hour, however, the noise and confusion died away. Each man knew his load, and had apparently become reconciled to it, however much it might be against the grain.” 23

Eventually they were ready to leave with Chuma in the lead, followed closely by Makatubu Wadi Songaro who was from Nyasa (Malawi) and who acted as the quartermaster. He was highly praised by Thomson for his energy but lacked Chuma’s leadership skills. The huge column marched out of Dar-es-Salaam on 19th May.

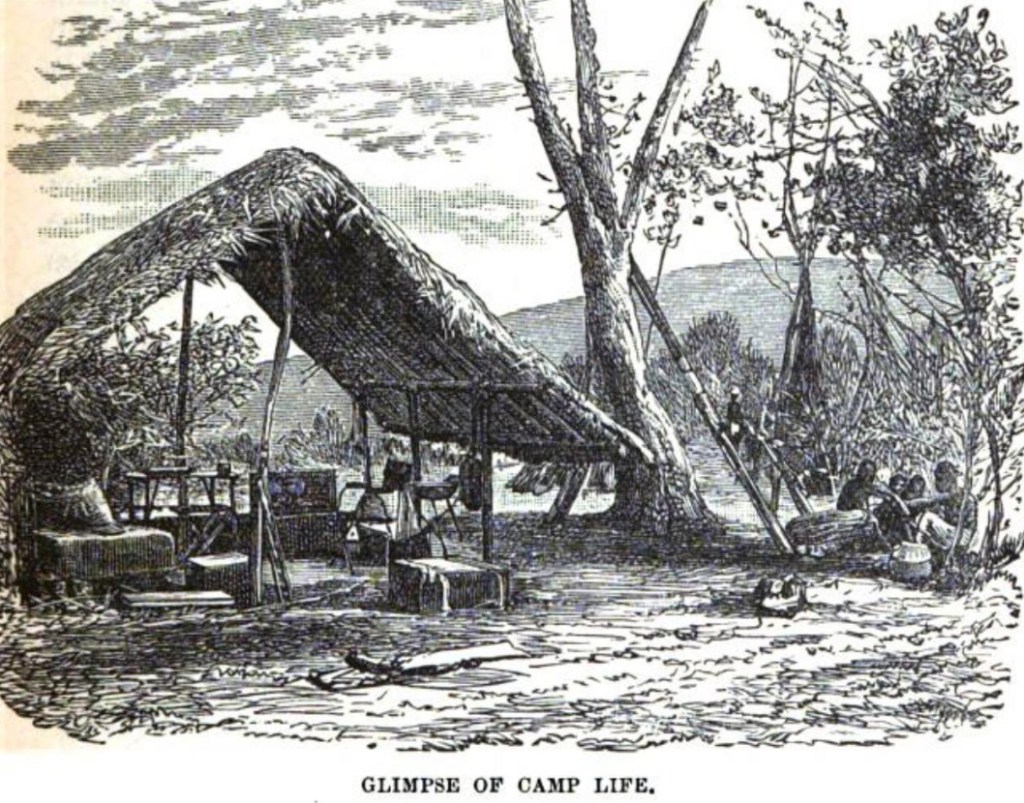

Both the Europeans found the going tough and Johnson began to feel unwell after being completely immersed a river when attempting to shoot a hippo. It was raining incessantly, they were constantly soaked to the skin and were unused to walking long distances in hot and humid conditions. Johnston started to fall behind while Thomson staggered like a drunk at the head of the column. At the end of an early, gruelling march, they were both unwell and confined to camp for three days:

“The tents were pitched, and a boma, or thorn fence formed, inside which the men made their huts. For three days we were confined in our tents hors de combat, and unable to do anything.

Chuma, however, was equal to the occasion, and kept everything in order. It is under such circumstances that the value of a man like Chuma is understood. One with less influence and tact would be unable to keep down riot and disorder. One with less honesty would certainly take the opportunity to help himself in various ways.”

On June 28th Johnston died from dysentery at Kwa Chinda but the twenty-one year old Thomson decided to carry on regardless. He was now, even more reliant on Chuma’s experience and leadership skills.

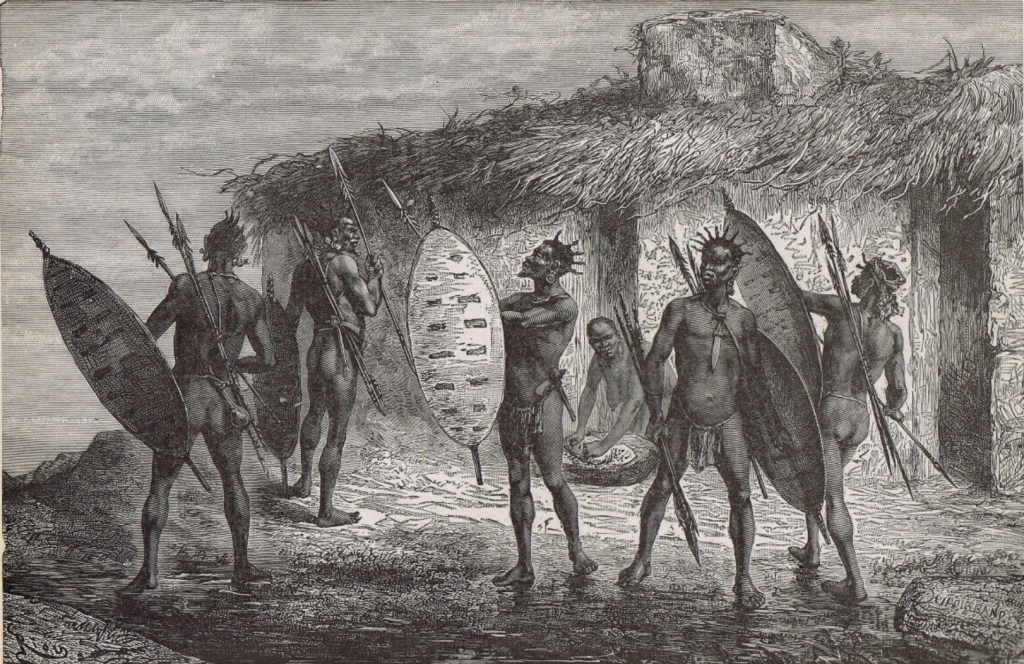

In mid-July they were entering the country of the Mahenge people, and Thomson had heard rumours that they were dangerous. He explains the need for vigilance to Chuma but that, given their weaponry and if they stick together, there should be nothing to fear.

“As the evening shade was falling, and the ruddy glare of the fires lit up the scene, the drums were beat, and an eager throng of men gathered round to hear what was to be done. Chuma took up a prominent position on some bales, and commenced his harangue.

He had not got through three sentences till I felt that I was listening to an orator, as he threw his whole soul into the work. He swayed that gang of rude savages as no refined and polished speaker could have done, and roused their enthusiasm in such a way that I felt there was little reason to fear desertion that night.”26

However, although the people they met were well armed with spears and clubs they proved friendly enough and inspected Thomson as if he was “a curious animal about which they had heard strange stories.”

Thomson is quite unlike Livingstone or Stanley, much younger, less aloof and perhaps less confident: he tries building, what he calls, an “esprit de corps” among the men, taking them into his confidence and asking their opinions. He also wants to abolish flogging and replace it with a system of fines for misdemeanours but this is not appreciated; when he tests the idea nearly all the porters temporarily desert. To bring them back he has to promise to abandon fines and revert to more traditional punishments:

“They were accustomed to being flogged, they said, but fining they knew nothing of. A flogging lasted only for the minute, but were they going to travel so far and come back to find their money all fined away!”

Chuma proves himself to be an excellent caravan leader, keeping the heavily laden porters cheerful and on the move.

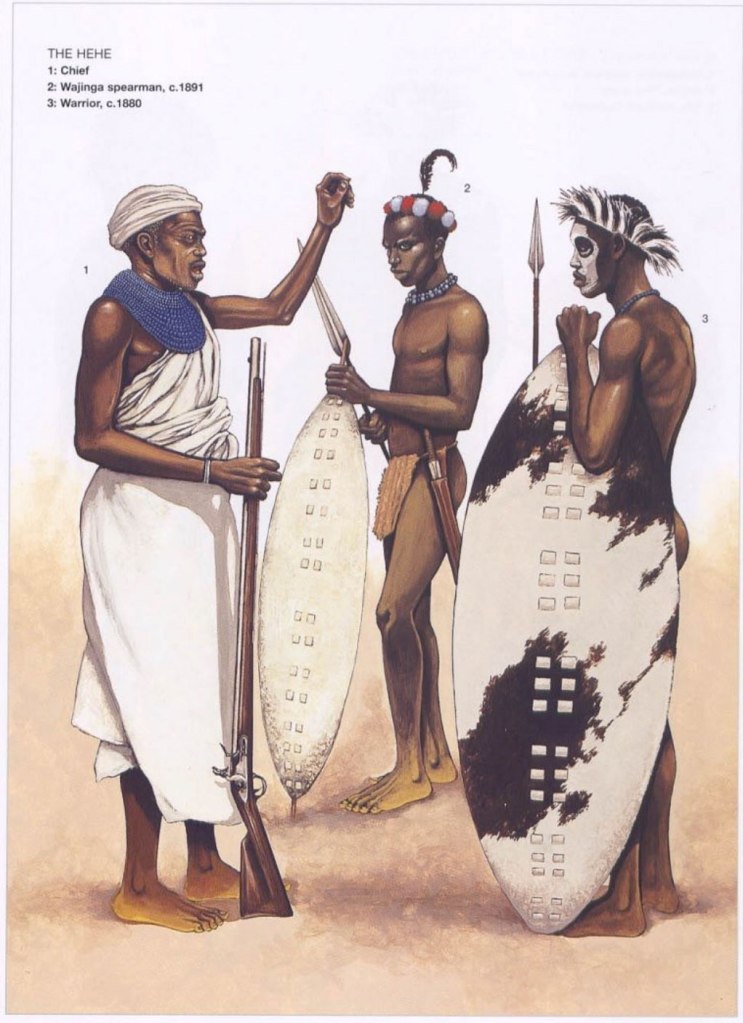

He also displays his diplomatic skills when they meet Chief Mamlé of the Wahehe people at Uhenge; Thomson shows the chief photographs of European ladies and Chuma elevates his master’s standing by explaining they are his wives.

Mamlé is suitably impressed and asks Thomson to send him a consignment of such fair ladies.

Mamlé wants to bond with Thomson by “making brothers” which entails cutting tribal marks into their bodies. This is done using proxies and Chuma is chosen to represent Thomson, with one of Mamlé’s headmen, representing the chief:

“The proxies sat down opposite each other with legs interlaced. The spear of the one and the gun of the other were placed across their respective shoulders.

An Mhehe then made three small cuts in the breast of Chuma, and Uledi, my gun-bearer, made the same on the chief’s breast, at which he visibly winced.

Thereafter another Mhehe took the axe of Mamlè’s proxy and rubbed it on the spear, making a speech the while, drawing down curses on the latter if he should break the brotherhood. Next Uledi took Chuma’s knife and rubbed it on his gun, and made a similar speech.

The ceremony was finished by a small piece of meat being taken and rubbed in the dripping blood of Chuma, and given to the headman to eat, the same being done for Chuma.”

The ceremony is concluded by a troop of naked women who dance all around a hugely embarrassed Thompson who tries to look everywhere except at the gyrating and naked bodies that surround him.

He tells his men to look the other way but, they of course, enjoy the spectacle.

The caravan reached the southern point of Lake Tanganyika on 3rd November. Chuma gave a signal and the men began to play “pan pipes”, blow horns, beat drums and shout “Tanganyika! Tanganyika” whilst firing their guns in the air. They gather at the edge of the lake and call the roll; quite incredibly for a nineteenth-century African expedition, of the 150 men who left Dar-es-Salaam there have been no deaths nor any desertions.

Like so many other travellers in central Africa in the late nineteenth century Thomson found large parts of the country ravaged by slavers and war. On the 4th November 1879 they reach Pambete on of the southern shores of Lake Tanganyika which Thompson recalls Livingstone had visited in 1867. Then it had been:

” a thriving and prosperous village, with its well cultivated fields, its groove of oil palms, and its fisheries.”

But, now:

“…… it had almost dwindled out of existence. Ruined huts were its principal features. Those still habitable were occupied by a few old men, myriads of hateful insects, and innumerable rats …. Few oil palms now remain; those trees having either been ruthlessly cut down during some war-raid, or killed by the rise of the waters of the lake.”

They travelled north on the western side of the lake. He wanted to look at the Lukuga River which Cameron had thought was the outlet from the lake, an idea he now thought unlikely. As they moved north they met the first slave caravan they had seen. It presented a distressing spectacle with both men and women chained together and with the women, often carrying children, bearing loads as well as the men. The skeletal children with blistered and bleeding feet stare at the caravan reproachfully.

They continued north to Lendwe (Chipasense or Kasaba bay) where the Lofu River (Lufuba River) flows into Lake Tanganyika. He described Lendwe as a densely inhabited and important Arab settlement only second to Ujiji in terms of both population and importance.

The caravan enters in great style:

“A new English flag replaced for the time being the torn and tattered Union Jack which had led us from Dar-es-Salaam. The men donned their best, while in front I myself marched, surrounded by a brilliantly-dressed bodyguard of head men, each carrying a handsome spear in his hand, and a gun slung on his back.

In the centre of this assemblage of dazzling colours and imposing turbans, I presented a considerable contrast in my sober, free-and-easy suit of Tweeds and pith hat. I had only a stick in my hand, and I carried my azimuth compass at my side, instead of guns and revolvers.

The caravan band, with its native drums, clarionet-like zomiri, and barghumi, or antelope horn, made an appropriate amount of noise as an accompaniment to the recitative of the fantastically dressed Kiringosis and the chorus of the rest of the porters.”

Thomson decides to push ahead for the Lukuga River with just thirty men and leaves Chuma with the rest of the caravan at Lendwe where there is plenty of food available. He puts Makatubu in charge of the reduced caravan but this eventually leads to trouble as he is not respected in the same way as Chuma. He finds that travel without Chuma is far less pleasurable.

When they return to Lendwe everything is in good order, Thompson finds:

“The only fault I had to find was that he had carefully selected all the bales with fine cloths in them, and being of a very gallant nature, with a soft side towards the female sex, he had been somewhat lavish in his gifts to such Iendwe damsels as had the good fortune to attract his attention.”

“Chuma had acted with much care and moderation, in spite of his somewhat extravagant character.”

The twenty-two year old Scotsman, who had not known where to look when entertained by naked female dancers, may have been too naive to consider what Chuma had been up to in his absence. This was the fellow who had been too busy enjoying “bange and black concubines” to accompany Livingstone to Cazembe’s in May ’67. 29

Thompson also found that he was now known as Chuma’s white man and the men danced all night to celebrate his return.

“And so through the livelong night they howled and sang, clapped hands, and generally threw themselves about, while the drums rolled out their volume of sound, and the zomiri screeched. …. When I appeared on the scene a shout was raised, and every one sprang to his feet. As if they had thoroughly rested, they formed a ring round me, and with a chorus and grand breakdown they finished the proceedings.”

They were unable to take a direct route to Bagamoyo on the coast because there was unrest in the country to the east of Tanganikya. Instead the caravan initially travelled northeast to Tabora and then on to the Indian Ocean at Bagamoyo.

They entered the town to be greeted by crowds of Arabs, Hindus and Swahili with much shooting and drumming. They had traveled 8,000 kilometres since leaving Dar-es-Salaam fourteen months earlier, the returning men were well dressed, well fed and in good spirits. When they called the final roll-call the only man who had been lost was Johnston, the original expedition leader.

On 16th July they landed back in Zanzibar and marched through the town to the British Consulate where they performed the war-dances they had learnt on their journey. The Sultan gave the men a present of 80 rupees.

Johnson’s account of his journey reveals a man who never preached to or judged his men, he accepted them as colleagues, not slaves or indentured servants and accepted their human failings and minor transgressions with good humour. He took no offence at being called Chuma’s white man which suggests a man comfortable in his own skin. It is easy to forget that he was only just twenty-one years old when they set out.

He had formed a close working relationship with James Chuma:

“Chuma and my second headman Makatubu have worked like heroes, and I should indeed be but a poor mortal if I did not acknowledge the fact that the success of the expedition has been to a large extent due to them. …… (Chuma) was ever at my elbow, with his ready tact and vast stores of information, ever ready to guide and direct me.”

I have written before about the dreadful slaughter of elephants in east and central Africa, a slaughter than fuelled and turbocharged the slave trade (here).

Johnson’s caravan walked for 8,000 kilometres from Dar-es-Salaam to the northern tip of Lake Malawi, north to the southern tip of Lake Tanganyika, half way up the western shore of the Lake and then back to Zanzibar via Taboro; a huge area of east Africa. Yet, they did not see a single elephant; he rejects the, then, acquired wisdom that the slave trade could be suppressed and replaced by the ivory trade. He points out the obvious flaw in this argument:

“Less than ten years ago Livingstone spoke about the abundance of elephants at the south end of Tanganyika how they came about his camp, or entered the villages with impunity: Not one is now to be found.

The ruthless work of destruction has gone on with frightful rapidity. There are few corners of Africa where they have not been harried out. ……. Not one great area can now be pointed out where the elephant can be said to roam unmolested.

The ivory trade has certainly reached its turning-point. Each year less ivory will be got, and the date is not far distant when hardly a tusk will find its way to the coast.”

The Temple Phipson-Wybrants Expedition 1880

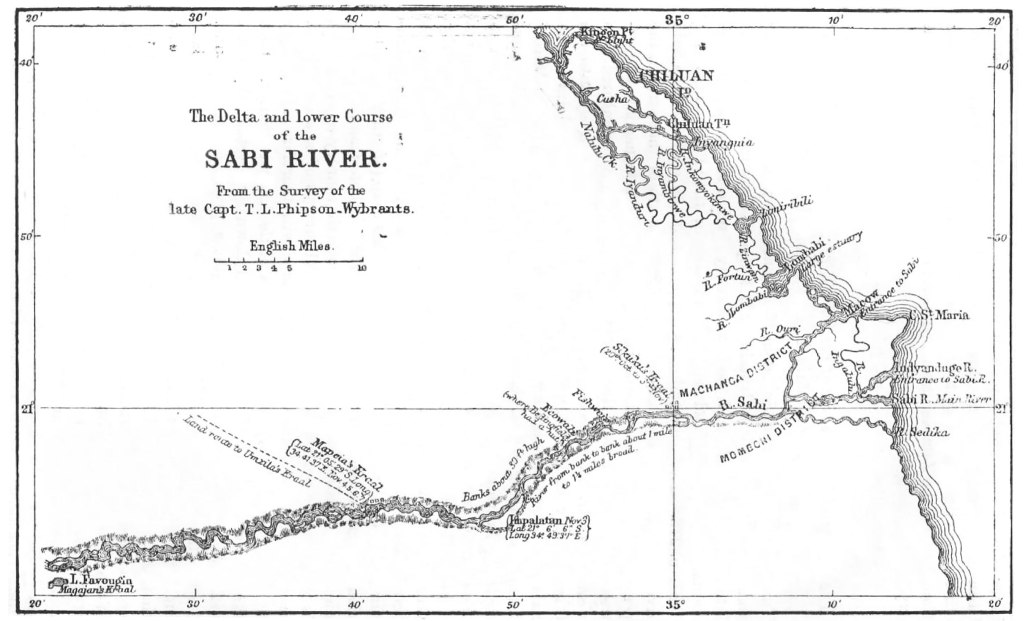

James Chuma was not home for long. In July 1880 he was employed as the caravan leader of one hundred men accompanying Captain Temple Phipson-Wybrants late of the 75th Regiment of Foot (The Gordon Highlanders) and four other Europeans on an expedition to explore the country between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers.

They took four months to reach the mouth of the Sabi River near Sofala and in October Phipson-Wybrants wrote to his mother assuring her that he was fit and healthy.

The expedition found it impossible to recruit guides and additional porters when at the mouth of the Sabi River without the express permission of Umzila, the senior chief, whose kraal was 250 miles away. Frustrated by the wait Phipson-Wybrants set off up river on the expedition’s steamer with Dr Mayes, one of the Europeans, and a Hindi pilot.

We know he surveyed the River in great detail as his hand-drawn maps were later published by the Royal Geographical Society. He returned to the main expedition party at Mapeia’s on 10th November.

The whole party then set out to reach Umzila’s kraal which lay in a northwesterly direction. They advanced in stages of around 15 miles a day but as the rains started Captain Wybrants died of “fever and sun-stroke” on 29th November at Macoupi’s. The expedition was now commanded by Dr. Ward Carr and returned to the mouth of the Sabi River but Carr died on February 14th 1881.32

Sometime in February 1881 the reports of Captain Wybrants’ death reached the outside world and on March 1st the Portuguese Governor of Mozambique Island sent the corvette Rainha de Portugal and the British sent HMS Wild Swan to find the expedition. 33

His gravestone, where he is buried in the Woolwich Old Cemetery (right) states that he died on November 29th 1880 aged 34 and his body was “recovered through his mother’s devotion”. 34

James Chuma survived the expedition but was away from Zanzibar from around July 1880 until, at least, March 1881.

At some point in 1880 his first wife N’taéka died.

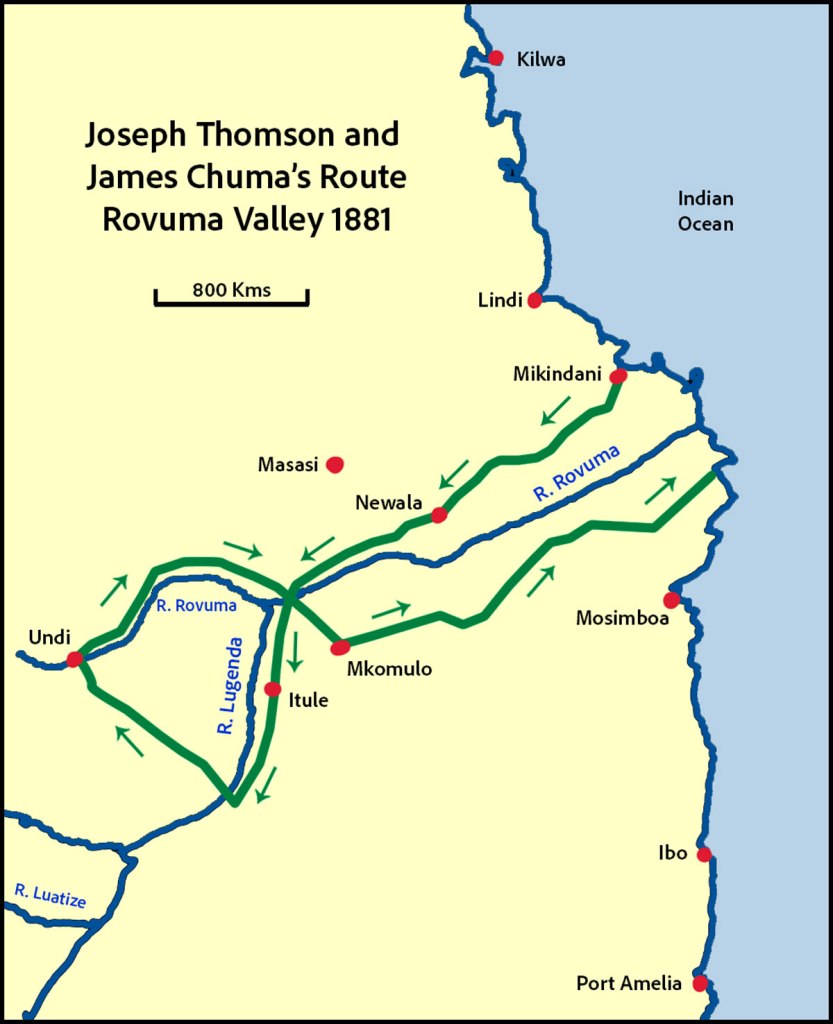

Joseph Thomson and the Rovuma Valley 1881

In June 1881 James Chuma’s old friend Joseph Thomson was back in Zanzibar and commissioned by Seyed Barghash, the Sultan of Zanzibar, to survey the Rovuma Valley to establish the “nature, extent and economic value” of the coal deposits that were said to exist there.

Thomson had arrived in Zanzibar just in time to help John Kirk, the Consul, distribute Royal Geographical Society medals to his erstwhile followers including James Chuma and Makatubu for their part in his expedition to Lakes Nyasa and Tanganiyka. They had just returned from Captain Wybrands’ fateful expedition to the Sabi River.

On 14th July they landed at Mikindani and two days later headed inland with sixty porters. Once away from the coast Thomson noticed that many of the villages that Livingstone had seen along the Rovuma had now gone and large areas of the country had been depopulated. As a consequence the country is “literally swarming” with waterbuck, bushbuck, eland, kudos, wildebeest, hartebeest, buffalo, quagga, zebra, warthog, lions, leopards, wild dogs and hyenas as well as “many of the larger animals” which tantalisingly he doesn’t list.

Thompson completes his survey as they walk in a large loop around the Rivers Lugenda and Rovuma. He makes interesting observations about the various people they encountered:

“There were the massively tattooed Makondè, with their curious combination of sexual morality with periodical pombe (native beer) debaucheries. There were the Maviti, the raiders and bullies of the region, with their Zulu war customs and destructive genius.

There were the intelligent and industrious Wayao [Yao] (to which tribe Chuma belonged), with their cleanly habits and keen trading instincts. There were the Makua with their advanced ideas on the rights of woman.

The image right is a modern Makonde mask 35

They returned to the coast south of Cape Delgado on 10th September 1881. 36

A Short but Stirring Life

I have found no record of Chuma travelling again after arriving back in Zanzibar in September 1881.

He had married Salima binti Sitakishauri 37 sometime after N’taéka died but the dates are elusive.

James Chuma died of tuberculosis in Zanzibar in 1882, his will was dated 25th September ’82, and he appointed Abdullah Susi as one of his executers and to whom he left half of his estate.

On his death Joseph Thomson wrote:

“A loss, however, I felt more immediately than that of Dr. Steere, was that of the well-known Chuma whom I hoped to have again with me as head-man. He also had died after a short but stirring life, having in his own special way, done so much to open up Africa to science and communication.” 38

James Chuma was one of most widely travelled of all the black explorers. Starting with a six hundred kilometre walk from Magomero to the Indian Ocean and finishing with the Thompson Rovuma Valley Expedition, he probably walked around 25,000 kilometres across east and central Africa. He made a return voyage across the Indian Ocean, took a trip to Britain and sailed many times between Zanzibar and the mainland.

A modern tourist would have passport stamps from Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, The Democratic Republic of the Congo, the United Kingdom and India.

He traveled with some of the most famous adventurers and explorers of the age: David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley, Keith Johnston and Joseph Thomson and knew Dr. John Kirk well. He lived and travelled with the first UMCA Bishops: Mackenzie, Tozer, Steere and Maples.

Yet he was just 32 when he died, a short but stirring life indeed.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Footnotes

- To the Editor of the Times – https://onemorevoice.org/html/transcriptions/liv_020012_TEI.html ↩︎

- Council for World Mission archive, SOAS Library © Council for World Mission, CWM/LMS/Livingstone Pictures/Box 1, file 8 ↩︎

- A.E.M. Anderson-Morshead (1899) The History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa 1859-1898. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001117/00001/2x ↩︎

- A National school was a school founded by the National Society for Promoting Religious Education. ↩︎

- Anita McCullough () Rev. Horace Waller: Dr David Livingstone’s friend in Leytonstone http://www.leytonhistorysociety.org.uk/Horace%20Waller%20-%20Dr%20Livingstone’s%20friend%20in%20Leytonstone.pdf ↩︎

- Gertrude A. T. Frere (1902) Where Black Meets White: The Little History of the UMCA. London: UMCA (Forgotten Books Edition) https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/WhereBlackMeetsWhite_10052176#6 ↩︎

- Alastair Hazel (2011) The Last Slave Market. London Constable ↩︎

- G. Alex Bremner (2009) The Architecture of the Universities’ Mission

to Central Africa https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/8214946/The_Architecture_of_the_Universities_Mission_to_Central_Africa_Developing_a_Vernacular_Tradition_in_the_Anglican_MIssion_Field_1861_1909.pdf ↩︎ - Rev. R. M. Henley (1909) A Memoir of Edward Steere, Third Missionary Bishop in Central Africa. London: UMCA (Forgotten Books edition) https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/AMemoirofEdwardSteereDDLLD_10209024#4 ↩︎

- Edward A. Alpers (1969) Trade, State and Society Among the Yao in the Nineteenth Century. https://www.jstor.org/stable/179674?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Gindo is a surname common in the Congo Basin and to the east of Lake Malawi in Tanzania. ↩︎

- Makua https://www.101lasttribes.com/tribes/makua.html ↩︎

- Edward Steere (1876) A Walk to the Nyassa Country. Zanzibar: Universities Mission Press https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t71v5vf8k&seq=1 ↩︎

- Edward A. Alpers (1969) Trade, State and Society Among the Yao in the Nineteenth Century. https://www.jstor.org/stable/179674?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Gertrude A. T. Frere (1902) Where Black Meets White: The Little History of the UMCA. London: UMCA (Forgotten Books edition) https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/WhereBlackMeetsWhite_10052176#6 ↩︎

- https://dl.atla.com/concern/works/41687q71f?locale=en ↩︎

- Seemingly used here as a general description of southwest Tanzania, northwest Mozambique and Malawi ↩︎

- Mbweni was the settlement of liberated slaves on Zanzibar Island founded by Bishop Tozer. ↩︎

- The photo is of a termite mound furnace in Benin but one assumes that the furnaces in Tanzania would have been similar. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Examples-of-traditional-granaries-and-furnace-constructed-with-termite-mound-soil-a_fig5_321185445 ↩︎

- Ellen Maples (1897) Chauncy Maples, D.D., F.R.G.S. Pioneer Missionary in East Central Africa for Nineteen Years And Bishop of Lake Likoma, Nyasa A.D. 1895 https://anglicanhistory.org/africa/umca/maples/01.html ↩︎

- G. Alex Bremner (2009) The Architecture of the Universities’ Mission

to Central Africa https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/8214946/The_Architecture_of_the_Universities_Mission_to_Central_Africa_Developing_a_Vernacular_Tradition_in_the_Anglican_MIssion_Field_1861_1909.pdf ↩︎ - Joseph Thomson (1881) To the Central African Lakes and Back. Vol I. London: Sampson Low, Marston , Searle and Rivington. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081905519&seq=11&q1=chuma ↩︎

- Joseph Thomson (1881) To the Central African Lakes and Back. Vol I. London: Sampson Low, Marston , Searle and Rivington. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081905519&seq=11&q1=chuma ↩︎

- https://www.rgs.org/media/3xmh1tlx/storiesfromeastafrica.pdf ↩︎

- J.B. Thomson (1896) Joseph Thomson, African Explorer, a Biography by his Brother with Contributions by Friends. London: Samsom Low, Marston and Co. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=3J8tAAAAYAAJ&pg=GBS.PA2&hl=en ↩︎

- Joseph Thomson (1881) To the Central African Lakes and Back. Vol II. London: Sampson Low, Marston , Searle and Rivington. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044072252877&seq=9 ↩︎

- https://safarisoko.com/traditional-music-and-dance-in-east-africa/ ↩︎

- https://livingstoneonline.org/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/TDC-South-East-Manyema-op82-article.jpg ↩︎

- Horace Waller (1874) The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa. London: John Murray https://archive.org/details/lastjournalsofda01livi/mode/2up?q=chuma ↩︎

- https://www.britannica.com/art/African-dance/Dance-style ↩︎

- Further explorations in the Mashona Country – Rhino Resource Centre http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/127/1279936469.pdf ↩︎

- Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (May 1883): The Delta and Lower Course of the Sabi River, According to the Survey of the Late Captain T. L. Phipson-Wybrants https://www.jstor.org/stable/1800112?read-now=1&seq=4#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (April 1881): Obituary of Captain T.L. Phipson-Wybrants https://www.jstor.org/stable/1800748?read-now=1&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Find a Grave: Captain T.L. Phipson-Wybrants https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10845547/temple_leighton-phipson_wybrants/photo ↩︎

- https://promptden.com/post/authentic-makonde-african-masks-tribal-tattoos ↩︎

- Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society Vol IV 1882 https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=TemfAAAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PP4&hl=en&q=rovuma ↩︎

- Donald Simpson (1975) Dark Companions: The African Contribution to the European Exploration of Africa. London: Paul Elek ↩︎

- https://www.rgs.org/about-us/our-work/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/black-geographers-past-present-future/hidden-histories-of-black-geographers ↩︎

Other Sources and Further Reading

- The Victorian Royal Navy is an incredible resource for anyone researching the nineteenth-century RN and/ or the slave trade. https://www.pdavis.nl/index.htm

- Rev. Pascoe Grenfell Hill (1844) Fifty Days on Board a Slave Vessel in the Mozambique Channel in April & May 1843. New York: J, Winchester, New World Press https://ia801307.us.archive.org/34/items/fiftydaysonboard1844hill/fiftydaysonboard1844hill.pdf

- Horrors of the Slave trade – The Progresso

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835-1869), 21 September 1843, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singfreepressa18430921-1.2.12.9 - Murder of Lieut. Molesworth The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835-1869), 15 August 1844 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singfreepressa18440815-1.2.6

- British and Foreign State Papers 1843-1844. London: J.Ridgeway and Sons https://archive.org/details/britishforeignst3218grea/page/n5/mode/2up?q=%22cape+of+good+hope%22

- Mrs Fred Egerton (1896) Admiral of the Fleet Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby. London: William Blackwood and Sons https://archive.org/details/cu31924027922479/mode/2up

- South African History Online – the Early Cape Slave Trade https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/early-cape-slave-trade

- Edward A Alpers (1970) The French Slave Trade in East Africa (1721-1810) https://www.jstor.org/stable/4391072?read-now=1&seq=43#page_scan_tab_contents

- Christopher Sanders (1985) Liberated Africans in Cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Gerald S. Graham (1967) Great Britain in the Indian Ocean: A Study of Maritime Enterprise 1810-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press https://archive.org/details/greatbritaininin0000grah/page/n7/mode/2up?q=slave

- A short description of Pascoe Hill’s life – https://www.wikitree.com/genealogy/Hill-Photos-39134/

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle.

- M.D.D. Newitt (1972) Angoche, The Slave Trade and the Portuguese 1844 – 1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/180760?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Brazil: Essays on History and Politics (2018) Britain and Brazil (1808–1914) https://www.jstor.org/stable

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle.

- Peter Collister (1980) The Sulivans and the Slave Trade. London: Rex Collings

- Christopher Saunders (1985) Liberated Africans in cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?seq=1

- Stephane Pradines (2019) From Zanzibar to Kilwa : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Omani Forts in East Africa https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343797763_From_Zanzibar_to_Kilwa_Eighteenth_and_Nineteenth_Century_Omani_Forts_in_East_Africa

- John Broich (2017) Squadron: Ending the African Slave Trade. London & New York: Overlook Duckworth

- Julien Durup The Diaspora of “Liberated African Slaves”!

In South Africa, Aden, India, East Africa, Mauritius, and the Seychelles https://www.blacfoundation.org/pdf/Libafrican.pdf - Philip Howard Colomb (1873) Slave Catching in the Indian Ocean: A Record of Naval Experiences. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Henry Rowley (1866) The Story of the Universities Mission to Central Africa, from its commencement, under Bishop Mackenzie, to its withdrawal from the Zambezi. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. https://archive.org/details/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/mode/2up

- David Livingstone (1865) A Popular Account of Dr. Livingstone’s Expedition to the Zambesi and its Tributies: and the Discovery of Lakes Shirva and Nyassa 1858 – 1864. Accessed at Project Guttenberg’s 2001 edition. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2519/2519-h/2519-h.htm

- Robert Keable (1912) Darkness or Light: Studies in the History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa Illustrating the Theory and Practice of Missions. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://missiology.org.uk/pdf/e-books/keable_robert/darkness-or-light_keable.pdf

- A.E.M. Anderson-Morshead (1899) The History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa 1859-1898. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001117/00001/2x

- E.D Young (1868) The Search After Livingstone, (A diary kept during the investigation of his reported murder). London: Letts Son, and co. The-Search-After-Livingstone

- Sir Henry M Stanley (1872) How I found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures and Discoveries in Central Africa. London: Samson Low, Marston and Company https://archive.org/details/howifoundlivings00stanuoft/howifoundlivings00stanuoft/page/n5/mode/2up?q=wellington

- Fred Morton (1990) Children of Ham: Freed Slaves and Fugitive Slaves on the Kenya Coast 1873 to 1907 https://www.academia.edu/41463426/Slavery_and_Escape_Excerpts_from_Children_of_Ham_Freed_Slaves_and_Fugitive_Slaves_on_the_Kenya_Coast_1873_to_1907

- Horace Waller (1874) The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa. London: John Murray https://archive.org/details/lastjournalsofda01livi/mode/2up?q=chuma

- Mrs. Charles E.B. Russell (1935) General Rigby, Zanzibar and the Slave Trade with Journals, Dispatches, etc. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd https://ia801501.us.archive.org/18/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.34110/2015.34110.General-Rigby-Zanzibay-And-The-Slave-Trade_text.pdf

- Rt. Hon. Sir Bartle Frere (1874) Eastern Africa as a field for missionary labour; four letters to His Grace, the Archbishop of Canterbury. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100371984

- Verne’s Lovett Cameron (1877) Across Africa Vol 1. London: Daldy, Isbister & Co https://archive.org/details/acrossafrica01came/page/n8/mode/1up?view=theater

- Eugene Stock (1899) The History of the Church Missionary Society: its environments, its men and its work https://archive.org/details/historyofchurchm03stoc/page/78/mode/2up?q=jacob

- Donald Simpson (1975) Dark Companions: The African Contribution to the European Exploration of Africa. London: Paul Elek

- Henry Rowley (1866) The Story of the Universities Mission to Central Africa, from its commencement, under Bishop Mackenzie, to its withdrawal from the Zambezi. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. https://archive.org/details/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/mode/2up

- Henry Morton Stanley (1878) Through the Dark Continent Vol I. London: Samson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.173877/page/n1/mode/2up

- Horace Waller (1874) The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 to his Death Vol. II. London: John Murray. https://archive.org/details/lastjournalsdav01livigoog/page/n6/mode/2up?q=stanley

- H.B.Thomas (1950) The Death of Doctor Livingstone: Carus Farrar’s Narrative https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/UF00080855/00028/11x

- Frank Debenham (1955) the Way to Ilala: David Livingstone’s Pilgrimage. London: Longmans, Green and Co. https://archive.org/details/waytoilaladavidl0000fran/page/4/mode/2up

- Joseph Thomson (1881) To the Central African Lakes and Back. Vol I. London: Sampson Low, Marston , Searle and Rivington. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081905519&seq=11&q1=chuma

- Joseph Thomson (1881) To the Central African Lakes and Back. Vol II. London: Sampson Low, Marston , Searle and Rivington. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044072252877&seq=9

- Petina Gappah (2020) Out of Darkness, Shining Light. London: Faber & Faber

- Andrew Ross (2005) David Livingstone https://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/151?lang=en

- Gertrude A. T. Frere (1902) Where Black Meets White: The Little History of the UMCA. London: UMCA (Forgotten Books edition) https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/WhereBlackMeetsWhite_10052176#6

- Alastair Hazel (2011) The Last Slave Market. London Constable

- Rev. R. M. Henley (1909) A Memoir of Edward Steere, Third Missionary Bishop in Central Africa. London: UMCA (Forgotten Books edition) https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/AMemoirofEdwardSteereDDLLD_10209024#4

- Edward Steere (1876) A Walk to the Nyassa Country. Zanzibar: Universities Mission Press https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t71v5vf8k&seq=1

- Arthur Cornwalls Madan (1887) Kiungani, or Story and History From Central Africa: Written by Boys in the Schools of the Universities” Mission to Central Africa. London: George Bell & Sons (Forgotten Books edition) https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/KiunganiorStoryandHistoryFromCentralAfrica_10122067#4

- Rev. Chauncy Maples (1880) Masasi and the Rovuma District in East Africa. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society June 1880. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1800473

- Ellen Maples (1897) Chauncy Maples, D.D., F.R.G.S. Pioneer Missionary in East Central Africa for Nineteen Years And Bishop of Lake Likoma, Nyasa A.D. 1895 https://anglicanhistory.org/africa/umca/maples/01.html

- J.B. Thomson (1896) Joseph Thomson, African Explorer, a Biography by his Brother with Contributions by Friends. London: Samsom Low, Marston and Co. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=3J8tAAAAYAAJ&pg=GBS.PA2&hl=en

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.