I was reminded this week of the remarkable story of the Bontebok, the first African antelope to be saved from extinction, dragged back from the precipice when there were just 17 left in South Africa.

©Steve Middlehurst

I feel very privileged to have encountered this magnificent animal twice. The first time was in 2008 and very much by accident; on our first visit to Cape Town we were driving from Simon’s Town to the rocky headland that forms the Cape of Good Hope. As we drove through the southern corner of the Table Mountain National Park we saw eight antelope standing in the Fynbos close to the road and with the Atlantic Ocean in the background. These were the first African antelope we had seen outside of a zoo but we had no idea what species they were and don’t recall trying to find out.

Fourteen years later, and by now very engaged with wildlife photography and Africa we visited the Bontebok National Park at Swellendam which is the smallest of South Africa’s national parks.

It is a beautiful little park easily explored by car in half a day.

With a little help from the rangers we found a small group of Bontebok near the fenced airfield. It was only then that I realised we had met before.

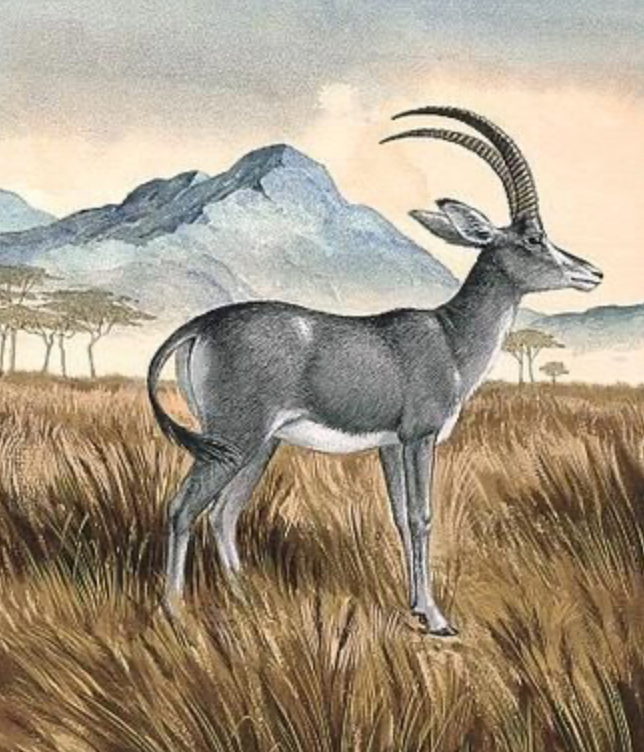

The Bontebok’s coat is a rich, glossy, chocolate-brown so deeply coloured that the top of its hind legs boast a purple sheen. Its lower limbs to above the knee, belly and backside are bright white.

The broad face is similar to the hartebeest to which it is related but the Bontebok sports a striking white blaze stretching from above its black nose to just below its eye sockets above which it narrows to a white stripe running up to and between its strongly ridged black horns.

The horns curve out and then backwards above elegant grey-brown ears. The male, who is easily recognised by his distinctive white scrotum is around a metre high at the shoulder and can weigh up to around 80kg, the female is a little smaller. It is a beautiful and elegant creature.

Map by Hugo Ahlenius, UNEP/GRID-Arendal

The Bontebok is an African antelope that few people have heard of and even fewer have seen. This is hardly surprising as there are only around 3,500 left in Africa and their natural habitat is the Fynbos Biome which is a unique plant kingdom occupying a narrow strip of land running round the bottom of Africa like a chinstrap beard.

©Steve Middlehurst

The Fynbos covers 85,000 km2, which sounds a lot but represents less that 7% of the Republic of South Africa and 0.3% of the African continent as a whole, Yet it is home to 9,600 plant species of which nearly 70% occur nowhere else on Earth.

Around 2,000 years ago the San people, who had lived here since the first humans arrived in southern Africa and whose way of life had little impact on their environment, were joined by the Khoikhoi people who were semi-nomadic herders. Their herds of cattle and sheep needed both grazing and water and the Khoikhoi used fire to clear areas of the Fynbos to promote the growth of grasses and so began a destructive process that was accelerated by successive waves of settlers.

Last year I wrote about how the seeds of extinction were sown long before the modern era (see here) and perhaps the most startling fact is that by 1700, just 44 years after Europeans had arrived at the Cape, settlers had exterminated every animal weighing over 50 kg from within a 200 km radius of Cape Town.

Some were wiped out to the point of extinction.

The Blue Antelope or Bluebuck was already in decline before settlers hunted it to extinction in the 18th century. It is possible that its preferred habitat had been the Pale-Agulhas Plain, the continental shelf south of Africa that becomes nutritious grasslands and savanna-like floodplains when global seas levels are low. (see here)

The Quagga, a sub-species of the plains zebra, hung on longer; William Burchell’s expedition shot them for food in the area of the Klaarwater mission (modern Griekwastad) but he makes no mention of them as he journeyed well over 700 kms to get there from the Cape including crossing the Karoo where they had once roamed in great numbers.

They were still seen in large herds as late as late as 1837 near the Vaal River but were ruthlessly hunted for meat, skins and to protect the grasslands required for domestic animals. The last wild Quagga was shot in 1878 and the last captive specimen died in Amersham Zoo in 1883.

The Southern Black Rhino, the largest sub-species of the Black Rhino was another large mammal that had been plentiful across what is now South Africa, and southern Namibia before the Europeans arrived. Little is know about this animal as no photographs exist but we do know that it was extinct as early as 1850.

©Steve Middlehurst

The Bontebok appeared destined to follow the Blue Antelope, Quagga and the Southern Black Rhino; its natural habitat was the Fynbos and its habitat requirements are very specific.

The Bontebok could no more leave the Fynbos than a Polar Bear be relocated to the Amazon.

As a species it appeared doomed, trapped by its dependance on a very particular and shrinking habitat. Its natural behaviour to migrate, in herds of up to 1,000 animals, across the Western Cape grazing areas of grassland brought it into constant contact with the settlers.

The settlers saw it as a direct competitor to their sheep and cattle; nourishing grassland was in short supply and the farmers saw the Bontebok, and everything else that lived on, or near their farms, as pests, vermin to be exterminated, in the same way as they had eradicated the Blue Antelope and the Quagga.

©Steve Middlehurst

By the early 1800s the Bontebok was thought to be extinct; despite walking 7,000 kms across the southern African veld between 1812 and 1815 William Burchell saw and shot just one Bontebok to add to his collection of specimens. He noted that they were already very scarce.

In 1837, Alexander van der Bijl, the owner of Nacht Wacht Farm in Arniston, a small seaside settlement community in the Western Cape, fenced off an area of his farm to protect a small herd of Bontebok. Van der Bijl’s motivations are lost in the mists of time but it is the earliest recorded example of direct action to save a threatened species from extinction.1 Apparently the fence can still be seen.

Van der Bijl’s efforts would have come to naught if the Bontebok had learnt to jump like many of its cousins. A Springbok can leap over 2 metres high and travel 15 metres in a single bound, the much heavier Kudu also does well in the animal olympics with 3.5 metre leaps and can easily clear a 2 metre fence from a standing jump.

The comparatively lightweight Bontebok, which is not much more than half the size of a Kudu, didn’t evolve to jump and so it never escaped from the basic livestock fencing at Nacht Wacht Farm. Eighty years later there were 30 Bonteboks at Nacht Wacht and when, in the late 1920’s, Peter Kuyper (“PK”) Albertyn, the 15th Captain of the Springboks, make 700 hectares available on Zeekoevlei farm to create a Bontebok reserve 17 Bontebok were rounded up and transferred to Zeekoevlei.2

The Bontebok survived rather than thrived at Zeekoevlei in what became the first Bontebok national Park in 1931 but the habitat was not ideal and to help preserve the species a number were moved to Thornkloof Farm at Grahamstown. In 1960 a new Bontebok National Park was established outside Swellendam and the Zeekoevlei population and a few animals from Thornkloof were moved to this new park which provided and still provides an ideal Fynbos habitat.

Other Bontebok from Thornkloof were relocated to, what is now, the Table Mountain National Park and to the De Hoop Nature Reserve. There are now thought to be 3,500 Bontebok living inside various parks and reserves and on private land in the landscape around Bredasdorp.

The Future

The original settlers in South Africa saw wildlife as a threat, vermin to be eradicated to enable the primacy of their domestic animals; the slaughter of indigenous wildlife continued unabated for three hundred years. These settlers were not exceptional, far from it.

Across the world our destruction of habitats and wildlife began as we transitioned from hunter gatherers to pastoralists and farmers. In a small country like England successive waves of farmers with ever improving tools and techniques slowly but surely cleared the forests until by the Roman period most of the lowlands were already covered by adjoining farms.3

The remnants of the forest fell to the axe in the 16th and 17th centuries to build ships or to produce charcoal for the fast growing iron industry.

Auroch, brown bear, wolf, wild boar, lynx and wild cat went locally extinct along with the trees.

Whether through farming, forestry, industrialisation, urbanisation or the search for minerals this process has been replicated across most of the world and more depressingly continues unabated. Few habitats remain intact and those that do are usually adversely affected by adjoining human activity or a changing climate that is probably also our fault.

There is no way back to the Garden of Eden. The solutions to protecting habitats, wildlife and the natural world are multifarious and complicated, lots of little threads that, when woven together, form small patches, but no more than patches, that can be applied to the ravaged surface of the planet.

Huge new areas are unlikely to be set aside solely for wildlife and the long term success of existing wildlife parks and reserves will increasingly depend upon how effectively they interact with and benefit their local communities. Commercially operated private reserves and parks will play a part and so, it appears, will hunting concessions however counterintuitive and repellent that idea might seem.

On the continent of Africa 19% of the landmass is protected as:

“a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.4“

However, when you look country by country it becomes obvious that few countries can afford to effectively manage their officially protected land.

The Republic of the Congo has set aside 42% of the country as protected but effectively manages less that a quarter of that, Zambia manages less than half of its 41%, Malawi about half of its 23%, and Mozambique less than a quarter of the 22% it has set aside.

According to Protected Planet only 37.7% of the total protected land is effectively managed and protected. By my simple calculation that means there is nearly 4 million square kilometres of officially designated protected land that is waiting, crying out, to be managed.

That is a land mass larger than India (2.97 million km2) and nearly as large as the whole of the EU (4.18 million km2).

Clearly this is a herculean task but as the charity African Parks has shown progress can be made when there is a political will inside any given country and financial support from outside. African Parks was formed in the year 2000, it now manages 200,000 km2 across 23 protected areas in 13 countries.

Efficiently managed protected land is vitally important but does not mitigate the need for humans to learn how to coexist with the rest of the natural world in the spaces, i.e. most of the surface of the planet, that we have already claimed as human habitat.

Alexander van der Bijl was exceptional and became one of the earliest conservationist-farmers by allowed a few wild animals that he saw were becoming rare to cohabit on his land. We know little of his motivations, he may have been purely altruistic or perhaps he wanted to breed Bontebok to eat or hunt but either way the model he found by accident is the template that progressive landowners and conservationists have adopted in the 21st century. Initiatives that preserve habitat and protect wildlife alongside or inside commercial farms and human settlements.

In his important book “Flowers for Elephants” Peter Martell describes how farmers, reformed poachers and cattle rustlers, wildlife vets and communities came together in Northern Kenya to heal the land bringing wild life, humans and domestic animals together in the same spaces.

Creating wildlife corridors to connect conservancies allowed free roaming and natural breeding patterns.5

Another micro-example, because all these initiatives will be microscopic in comparison with the scale of the problem, is the Bontebok’s home range in South Africa, where landowners and the residents of towns have come together in a manner similar to the Kenyan conservancies.

The Nuwejaars Wetlands Special Management Area (NWSMA) brings together 25 landowners and the town of Elim to protect the 47,000 hectare landscape that constitutes the hinterland of Cape Agulhas, the most southerly tip of Africa and where they farm and live.

Their aim is to pursue sustainable farming whilst protecting the landscape and wildlife of the Agulhas Plain. The Bontebok is one of many species that now thrives on the private land that makes up the NWSMA and where they are actively monitored and managed. They coexist with humans, and reintroduced leopards and hippos.

The IUCN continues to classify the Bontebok as “Vulnerable” having upgraded its status from “Critically Endangered” following conservation efforts. However it remains threatened by loss of habitat and cross breeding with Blesbok which are often kept on the same game farms.

Bontebok may never again roam in herds 1,000 animals strong but through the foresight of one Dutch farmer, the generosity of an international rugby captain, the work of South African National Parks and the NWSMA it has survived against all the odds and can still be seen roaming in the Fynbos Biome.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Footnotes and References

- Various places claim to be the first wildlife parks. The French colonists on Tobago established the Main Ridge Forest Reserve in 1783 to combat deforestation of the island. Between 1805 and 1821 Charles Waterton protected part of his estate at Walton Hall in Yorkshire to conserve native and migratory wildlife. Many ancient and medieval rulers declared large tracts of land to be exclusive royal hunting grounds and somewhat ironically a few have survived to this day as national parks that preserve local flora and fauna such as the New Forest in Southern England and the Hlane Royal National Park in Eswatini. ↩︎

- PK Albertyn’s house and farm at Cape Agulhas was incorporated into the Agulhas National Park in 1999. ↩︎

- Oliver Rackhan (2000) The History of the Countryside. London: Orion Publishing. ↩︎

- https://africageographic.com/stories/which-african-countries-have-the-highest-percentage-of-protected-land/ ↩︎

- Peter Martell (2022) Flowers for Elephants. London: Hurst Publishers ↩︎

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.