The Bombay Africans

The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) tells us:

“Originally forced into slavery in Africa, the group who came to be known as the ‘Bombay Africans’ were liberated by the British Royal Navy from Arab slaving boats and taken to Bombay (India) or Karachi (Pakistan).”

In practice the RGS description has been stretched to include four quite distinct groups of people:

- The Zambesians

- The Nasik Boys

- The Magomero Boys

- And, the Siddi People

The Zambesians

These were Africans from the Zambesi River who were probably never enslaved but travelled from Africa to India and spent some time there before returning to Africa.

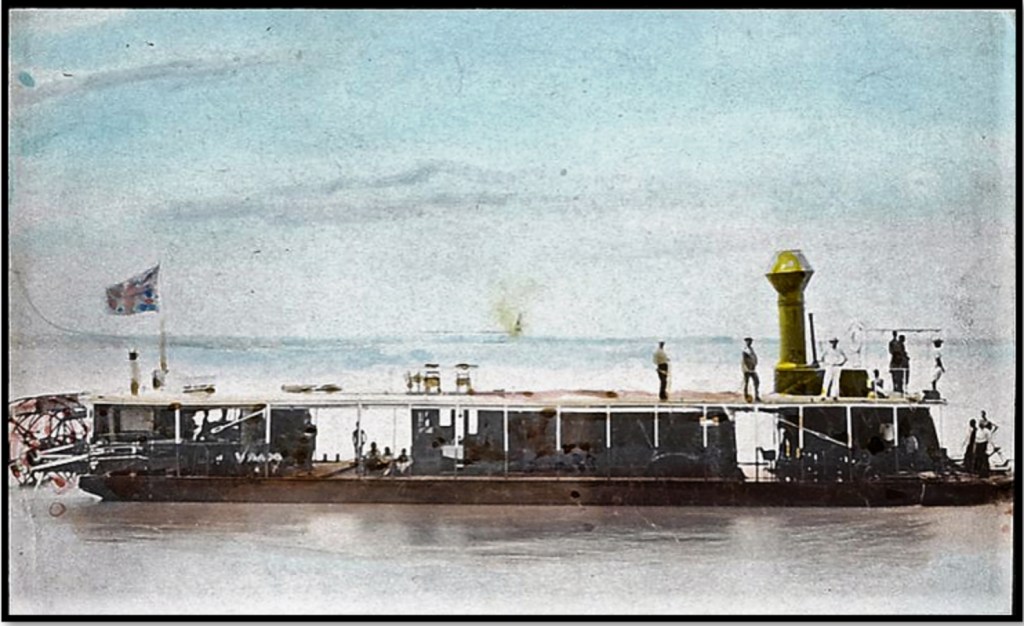

They include Abdulla Susi and Hamoydah Amoda who along with five other “Zambesians” had served as crew on Livingstone’s little steamer Lady Nyassa when she sailed from the Zambesi River to Bombay in 1864.

Susi and Amoda were from the El Balyuz (Chupanga) on the Zambezi River which is around 200 km inland from the Indian Ocean. They had previously been employed by Livingstone as wood cutters on his Zambesi expedition (1858 to 1864).

The Nasik Boys

The group who best fit the RGS definition are the Nasik Boys who were liberated as children from Arab dhows in the Indian Ocean by the Royal Navy and schooled at the Church Missionary Society (CMS) mission at Sharanpur. Fifteen of these boys returned to Africa to join Livingstone’s last expedition either in the initial party or as part of Stanley’s relief column.

The CMS and other missionary organisations believed that educated Christian Africans could play an important part in taking Christianity to Africa and this idea was part of the raison d’être for Sharanpur. Many boys and girls from here joined the mission at Rabai or the liberated slave settlement at Frere Town near Mombassa in Kenya.

The Mangomero Boys

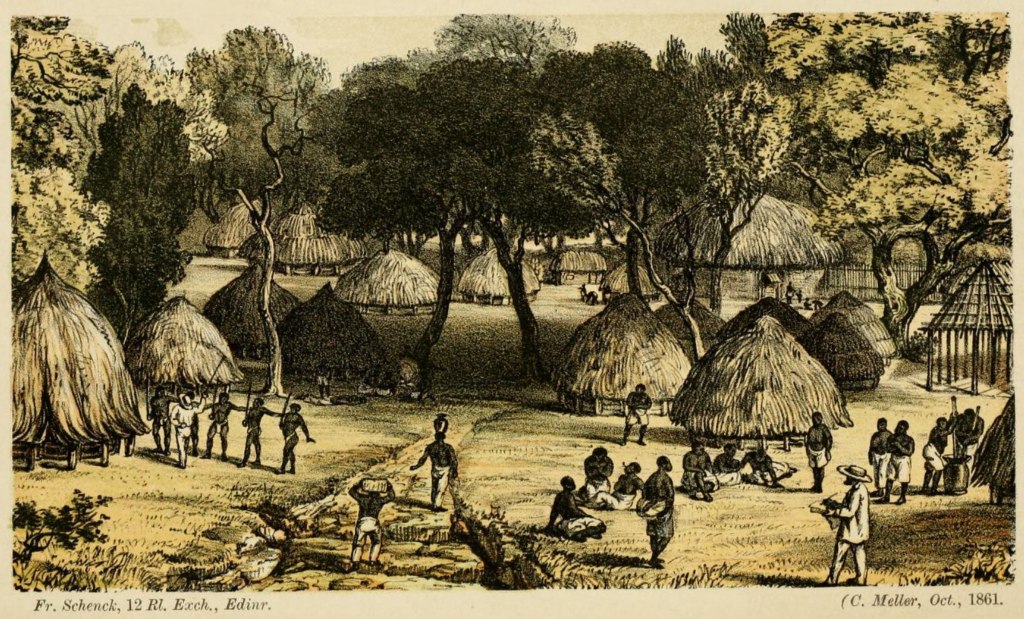

Then there are the Mangomero Boys: Chuma and Wekatani, who were rescued from slavers in Malawi; they initially lived at the Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) mission at Magomero and stayed with the missionaries when they withdrew to the Shire Valley and later to Mozambique.

Eventually they were taken to India by David Livingstone, schooled for a short time at Wilson’s College in Bombay and then returned to Africa as part of Livingstone’s expedition in search of the Nile (1866 to 1874). (For their stories see here and here)

The Siddi People

The Siddi people are a unique tribal group who live today as marginalised communities across India, in Goa, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat and in Karachi, Pakistan where they are known as Sheedi people. Their ancestry includes African, South Asian and European components but their heritage is predominantly Bantu from East and East Central Africa.

Some of their ancestors arrived on the Indian sub-continent with Arab slavers from as early as the seventh-century or as part of a second wave in the thirteenth-century with Portuguese slavers. The flow of slaves from Africa to India lasted for as long as thirteen-hundred years with some estimates suggesting that, in the nineteenth-century alone, as many as 347,000 enslaved people arrived in India via the Arabian Peninsular.

Some slaves rose to become nobles such as Malik Ambar (1548 to 1626) (see left), a slave from Ethiopia, who was purchased in Baghdad by the Chief Minister of Ahmadabad an Indian State in Gujarat.

The Chief Minister was himself a slave but on his death Ambar was freed and subsequently rose to rule Ahmadnagar, a State to the east of Mumbai.

Another freed African slave was Malik Raihan (see above) who became an advisor to a sultan’s son and progressed to high status and the command of the state’s army when the son became Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah.

Between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries the Janjira dynasty (see right) who were of African descent ruled a three-hundred kilometre stretch of the coasts between Mumbai and Goa.

The Janjira royal family were of Abyssinian (Ethiopian) descent whose ancestors had originally been in service to the Kings of Ahmadnagar, themselves ex-slaves. They rose to prominence as soldiers with a reputation of being great warriors and took possession of Dandarajpuri and the island of Janjira in 1490 initially on behalf of Malik Ahmad Shah.

They referred to themselves as “Siddis”, a term of respect with origins in Arabic, Marathi and Urdu.

Royal Academy of Arts

In 1843 Hosh Muhammad Sheedi (see right) commanded a 30,000 strong Talpur army against British East India Company forces under the command of Sir Charles Napier at the Battle of Hyderabad, sometimes called the Battle of Dubbo, which took place about twenty-five kilometres east of Hyderabad.

Napier won the day and the province of Sindh became a possession of the East India Company.

The slaves who rose to powerful positions were exceptions and African slaves were more often used as pearl divers, dock workers, miners, wet-nurses, concubines, domestic slaves, plantation labourers or as sailors, bodyguards and soldiers.

However, not all Africans settling in India were slaves or ex-slaves. Trade had existed between India and Africa since time immemorial carried by the monsoon winds that created one of the world’s oldest and most consistently reliable trade routes in the age of sail. Blowing anticlockwise from India, around the south coast of Arabia and down the east coast of Africa in winter and clockwise north up the African coast to the Arabian Sea and back down the west cost of India in the summer and autumn.

In the sixteenth-century the Sultans of Gujarat were employing African soldiers in their armies and it is open to debate whether these were slaves, ex-slaves or free mercenaries or a mixture of all of these. It is likely that the Africans who rose to power subsequently imported African mercenaries to bolster their military forces.

Liberated African Slaves and the Advent of Steam

In 1830 the East India Company began to convert its merchant fleet from sail to steam and in 1840 the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) sailed their first steamship, the S.S. Hindostan, from Southampton to Calcutta.

The voyage of the Hindostan heralded a new era of communication: soldiers, administrators, politicians, diplomats, merchants and young single women seeking husbands started to travel from Britain to its Empire and particularly to India, the so-called, Jewel in the Crown. Before long the official reports, government and military orders and the multitude of correspondence that kept the Empire running was on board P&O ships along with the passengers and private letters.

The age of sail in the Royal Navy was coming to an end and HMS Dee, the Navy’s first paddle steamer was launched in 1832 and was patrolling the Mozambique Channel hunting for slavers by 1849 (see here).

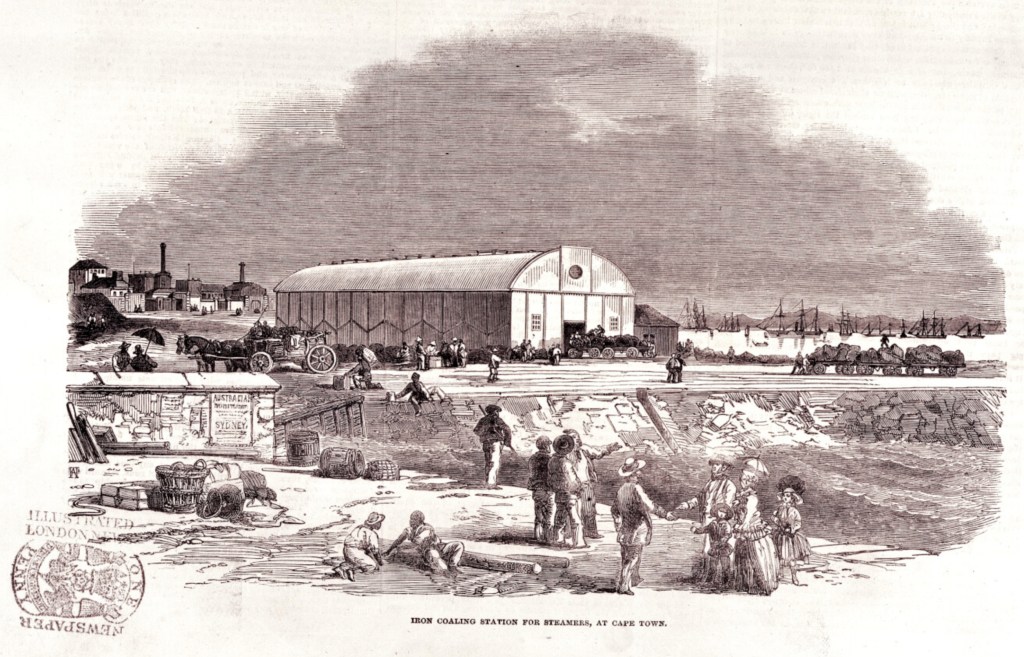

At the beginning of 1854 Messrs. Walton and Bushel, merchants, of the Cape, had a large iron building erected at the end of the Central Jetty, intended to hold 2500 tons of coal. The Governent gave them every assistance by a grant of land on which it stands. Iron. tramways were laid down direct from the interior of the building to the end of the jetty, so the steam-ships cain now be coaled in Table Bay, with almost as great facility as London.”

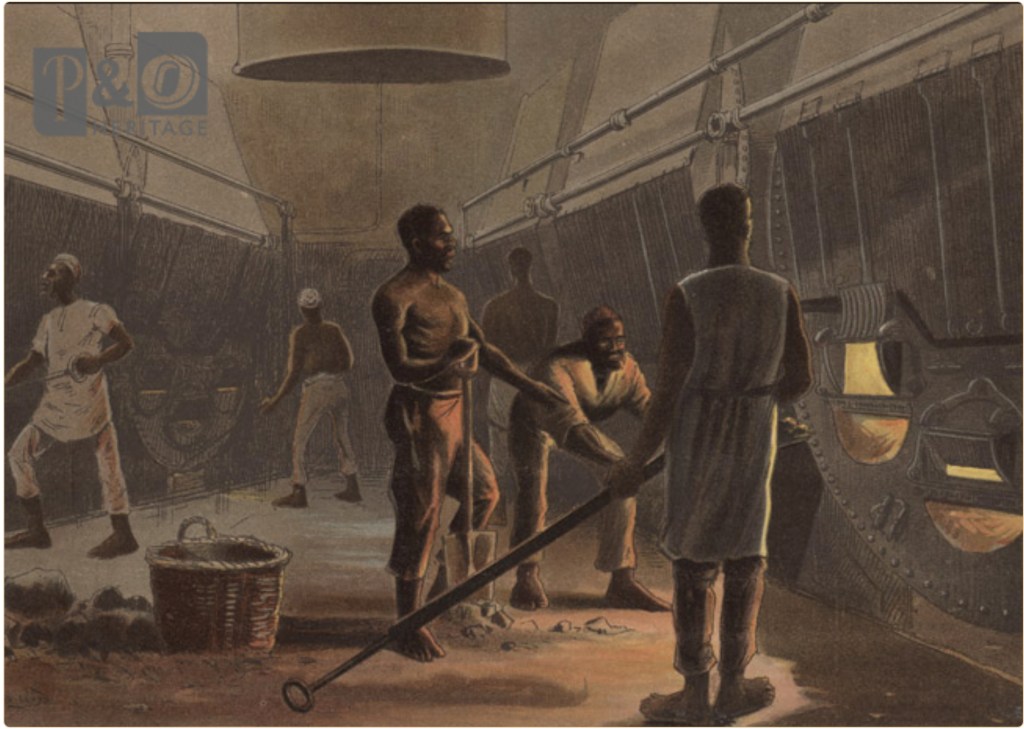

The Empire’s military and commercial communication network was supported and enabled by defended coaling stations which, on the India route, included Gibraltar, Sierra Leone, Simon’s Town (Cape of Good Hope), Durban, Aden, Mauritius and all the major ports in India. The new ships ran on coal, huge quantities of coal, that had to be replenished at every opportunity, loaded by hand and deep below decks, in the stokehold, shovelled into the boilers by hand.

The arrival of liberated African slaves in Bombay, Aden and Cape Town coincided with this particular facet of the industrial revolution. They found employment in the dockyards and coaling stations as labourers and mechanics and on ships as stokers, firemen and engineers’ assistants.

Across the ports and coaling stations of the Indian Ocean there were Siddis of African descent, mixing with Africans and Madagascans who by fair means or foul had found their way to these ports seeking employment as migrants or liberated slaves. And, of course, many other people including Pathans and Punjabis Indians, Somalis and Yemeni Arabs also found employment in these same ports.

Aden had been absorbed into the British Empire in 1839 and established as a coaling station. Its strategic position on the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsular, close to the entrance to the Red Sea and halfway between the Africa and India meant it developed into one of the busiest ports in the world.

Between 1839 and 1856 the population of the port grew from 1,300 to 21,000 and many of those people were Sidis (or Seedies) who had come to Aden, not just from India, but as escaped or manumitted slaves from Arabia and Arabian ships, runaway slave-pearl-divers from the Red Sea and freed or escaped African slaves from the Swahili Coast and Zanzibar. They were all seeking employment.

All at Sea

The same model was repeated in Durban where a “Sidee” community grew up around the docks and at Simon’s Town on the Cape where “Siddees” or “Sidhis” arrived from East Africa, the Seychelles and Zanzibar as freed slaves, indentured labour, and off Royal Navy ships. They mixed in with Kroomen who were freemen from West Africa with a long history of serving on British warships.

The British Admiralty had employed Kroomen at Simon’s Town since 1838 when the first West African Kru people were landed there from HMS Melville.

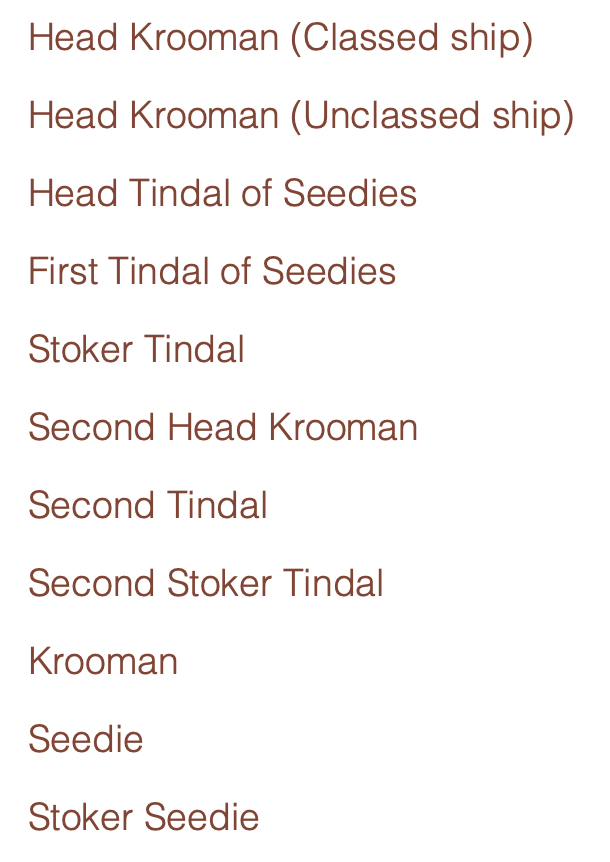

The Royal Navy depended on order and the ranks assigned to Kroomen (see left) not only reveal the hierarchy and structure of life on a British warship but show that Siddi (Seedie) stokers were in the mix albeit starting on the bottom rung.

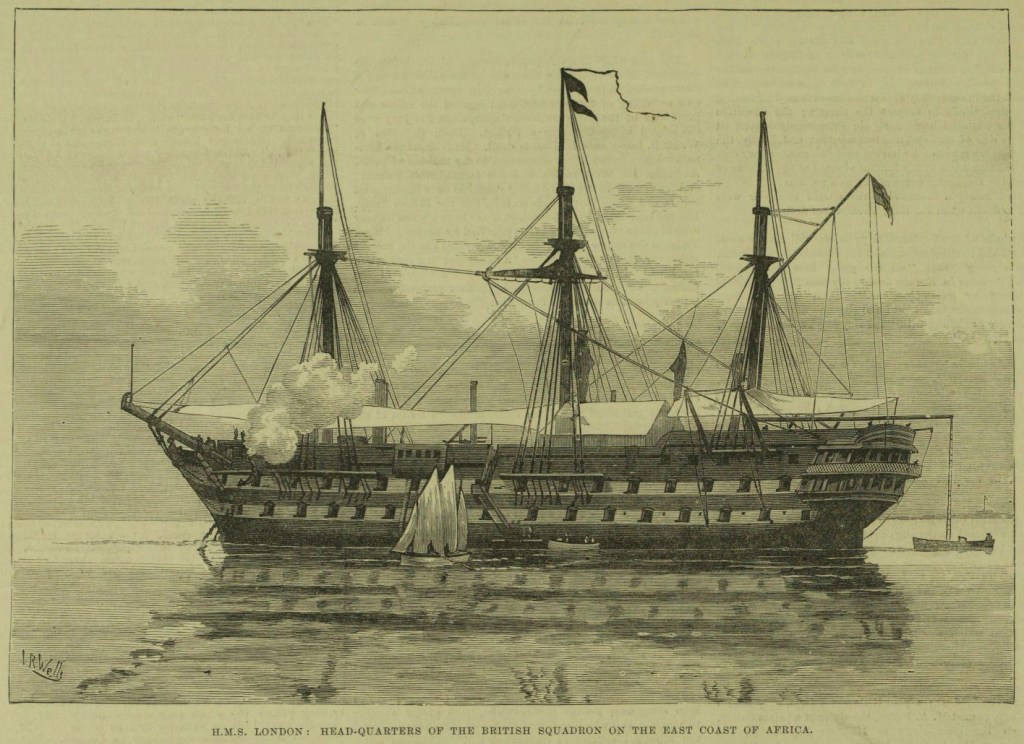

HMS London, based in Zanzibar, played an important role in the Royal Navy’s anti-slaving operations in the Indian Ocean in the second half of the nineteenth century and her crew included both locally recruited Krooman and Seedies (Siddis).

“Kroomen” was the Royal Navy’s name for Kroo or Kru people from the coast of Liberia and the Ivory Coast who were initially recruited as pilots.

They were skilled fishermen and accomplished boatmen and became an essential part of the West Africa Squadron’s efforts to suppress the slave trade.

Over time the terms “Seedies” and “Kroomen” seem to have become synonymous.

The image left is of Kroo fishermen by Elisée Reclus

In the Royal Navy the terms Krooman, Tindal and Seedie were still in use as ranks for ” Locally Entered Personnel” at the beginning of the First World War. In 1913 a Krooman was paid one shilling a day as compared to a British ordinary seaman who was paid one shilling and three pence a day. (£0.05 versus £0.0625, so 20% less).

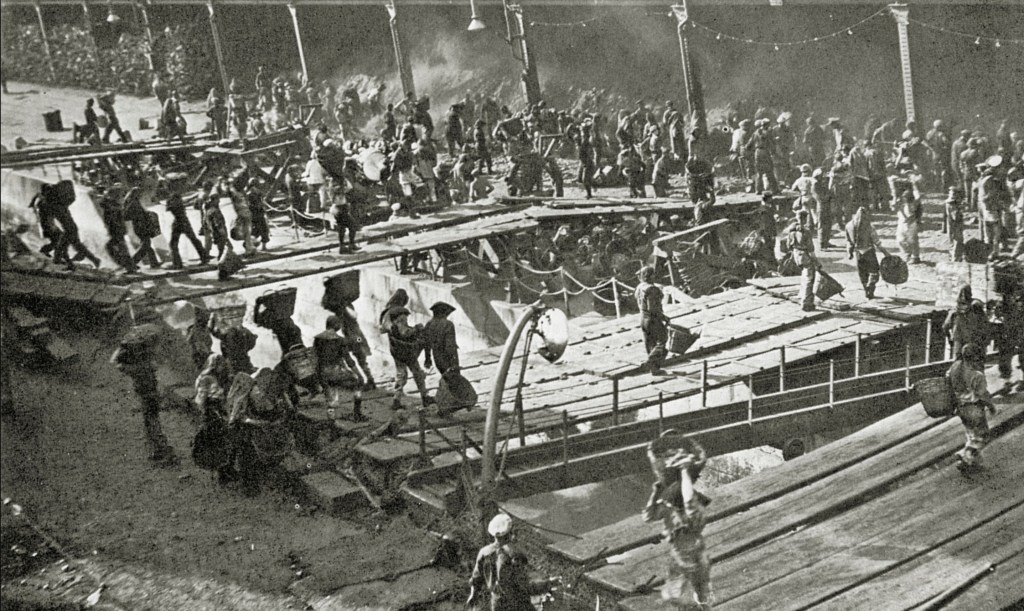

In the 1860s and 70’s Siddi dockworkers were joining the ships that filled the harbours of the coaling stations around the Indian Ocean and “more than half the two thousand Africans living in Bombay earned their living as sailors or in related maritime work.“

A British purser working on a British merchant or passenger ship employing stokers in the 1860s was unlikely to be too fussy about accurately recording ethnicity so, Africans could be taken on board as Siddis (Seedies) or as “lascars”, the generic term for sailors recruited by British ships east of the Cape of Good Hope and as, we have already seen in the Royal Navy, Siddis were often confused with Kroomen.

Published by P&O with the caption: “For steamers, you had to have coal. That was difficult and dirty enough. Then you had to have stokers, frequently “seedies” from East Africa, and the “stoke-hole” where they had to work was indescribable.’

Drawing by W.W.Lloyd first published in 1890.

The British Government had a long history of controlling maritime industries and the employment of lascars and Siddis on British merchant and passenger ships was carried out under “Asiatic Articles” which set their wages at one-fifth to one-third of European sailors, defined the length of their contracts and prohibited them from staying-on in British ports.

Not only were they cheap labour but they were easier to manage, less prone to drunkenness and cost less to feed than a British sailor; so, as a consequence, by the middle of the nineteenth-century ten to twelve thousand lascars were sailing on British ships with sixty percent having been recruited in Indian ports.

By the end of the nineteenth-century ten percent of all the sailors on British merchant and passenger ships were lascars and by the beginning of the First World War this had risen to over seventeen percent or nearly 52,000 sailors.

A Forgotten History

By depositing freed slaves in Bombay, Aden and Cape Town and by giving them employment as sailors under the Asiatic Articles the British created a peripatetic workforce with no fixed abode. Many Siddis drifted from port to port and ship to ship whilst others became soldiers and bodyguards in Arabia and Zanzibar and eventually absorbed into new communities.

There are still marginalised Siddi communities in India and Pakistan as well as displaced settlements in Kenya and South Africa. It seems that the their history is generally ignored or forgotten.

The East African slave trade and its suppression left a long-lasting, dark shadow right across the Indian Ocean.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Sources and Further Reading

- The Victorian Royal Navy is an incredible resource for anyone researching the nineteenth-century RN and/ or the slave trade. https://www.pdavis.nl/index.htm

- Rev. Pascoe Grenfell Hill (1844) Fifty Days on Board a Slave Vessel in the Mozambique Channel in April & May 1843. New York: J, Winchester, New World Press https://ia801307.us.archive.org/34/items/fiftydaysonboard1844hill/fiftydaysonboard1844hill.pdf

- Horrors of the Slave trade – The Progresso

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835-1869), 21 September 1843, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singfreepressa18430921-1.2.12.9 - Murder of Lieut. Molesworth The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835-1869), 15 August 1844 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singfreepressa18440815-1.2.6

- British and Foreign State Papers 1843-1844. London: J.Ridgeway and Sons https://archive.org/details/britishforeignst3218grea/page/n5/mode/2up?q=%22cape+of+good+hope%22

- Mrs Fred Egerton (1896) Admiral of the Fleet Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby. London: William Blackwood and Sons https://archive.org/details/cu31924027922479/mode/2up

- South African History Online – the Early Cape Slave Trade https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/early-cape-slave-trade

- Edward A Alpers (1970) The French Slave Trade in East Africa (1721-1810) https://www.jstor.org/stable/4391072?read-now=1&seq=43#page_scan_tab_contents

- Christopher Sanders (1985) Liberated Africans in Cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Gerald S. Graham (1967) Great Britain in the Indian Ocean: A Study of Maritime Enterprise 1810-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press https://archive.org/details/greatbritaininin0000grah/page/n7/mode/2up?q=slave

- A short description of Pascoe Hill’s life – https://www.wikitree.com/genealogy/Hill-Photos-39134/

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle.

- M.D.D. Newitt (1972) Angoche, The Slave Trade and the Portuguese 1844 – 1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/180760?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Brazil: Essays on History and Politics (2018) Britain and Brazil (1808–1914) https://www.jstor.org/stable

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle.

- Peter Collister (1980) The Sulivans and the Slave Trade. London: Rex Collings

- Christopher Saunders (1985) Liberated Africans in cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?seq=1

- Stephane Pradines (2019) From Zanzibar to Kilwa : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Omani Forts in East Africa https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343797763_From_Zanzibar_to_Kilwa_Eighteenth_and_Nineteenth_Century_Omani_Forts_in_East_Africa

- John Broich (2017) Squadron: Ending the African Slave Trade. London & New York: Overlook Duckworth

- Julien Durup The Diaspora of “Liberated African Slaves”!

In South Africa, Aden, India, East Africa, Mauritius, and the Seychelles https://www.blacfoundation.org/pdf/Libafrican.pdf - Philip Howard Colomb (1873) Slave Catching in the Indian Ocean: A Record of Naval Experiences. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Henry Rowley (1866) The Story of the Universities Mission to Central Africa, from its commencement, under Bishop Mackenzie, to its withdrawal from the Zambezi. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. https://archive.org/details/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/mode/2up

- David Livingstone (1865) A Popular Account of Dr. Livingstone’s Expedition to the Zambesi and its Tributies: and the Discovery of Lakes Shirva and Nyassa 1858 – 1864. Accessed at Project Guttenberg’s 2001 edition. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2519/2519-h/2519-h.htm

- Robert Keable (1912) Darkness or Light: Studies in the History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa Illustrating the Theory and Practice of Missions. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://missiology.org.uk/pdf/e-books/keable_robert/darkness-or-light_keable.pdf

- A.E.M. Anderson-Morshead (1899) The History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa 1859-1898. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001117/00001/2x

- E.D Young (1868) The Search After Livingstone, (A diary kept during the investigation of his reported murder). London: Letts Son, and co. The-Search-After-Livingstone

- Sir Henry M Stanley (1872) How I found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures and Discoveries in Central Africa. London: Samson Low, Marston and Company https://archive.org/details/howifoundlivings00stanuoft/howifoundlivings00stanuoft/page/n5/mode/2up?q=wellington

- Fred Morton (1990) Children of Ham: Freed Slaves and Fugitive Slaves on the Kenya Coast 1873 to 1907 https://www.academia.edu/41463426/Slavery_and_Escape_Excerpts_from_Children_of_Ham_Freed_Slaves_and_Fugitive_Slaves_on_the_Kenya_Coast_1873_to_1907

- Horace Waller (1874) The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa. London: John Murray https://archive.org/details/lastjournalsofda01livi/mode/2up?q=chuma

- Mrs. Charles E.B. Russell (1935) General Rigby, Zanzibar and the Slave Trade with Journals, Dispatches, etc. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd https://ia801501.us.archive.org/18/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.34110/2015.34110.General-Rigby-Zanzibay-And-The-Slave-Trade_text.pdf

- Rt. Hon. Sir Bartle Frere (1874) Eastern Africa as a field for missionary labour; four letters to His Grace, the Archbishop of Canterbury. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100371984

- Verne’s Lovett Cameron (1877) Across Africa Vol 1. London: Daldy, Isbister & Co https://archive.org/details/acrossafrica01came/page/n8/mode/1up?view=theater

- Eugene Stock (1899) The History of the Church Missionary Society: its environments, its men and its work https://archive.org/details/historyofchurchm03stoc/page/78/mode/2up?q=jacob

- Donald Simpson (1975) Dark Companions: The African Contribution to the European Exploration of Africa. London: Paul Elek

- Henry Rowley (1866) The Story of the Universities Mission to Central Africa, from its commencement, under Bishop Mackenzie, to its withdrawal from the Zambezi. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. https://archive.org/details/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/mode/2up

- Albert Mwamburi (2024) Bombay Africans; Forgotten Builders of Frere Town Mombasa, 19th Century https://pwanitribune.com/index.php/2023/10/05/bombay-africans-forgotten-builders-of-frere-town-mombasa-19th-century/

- Sir Richard Francis Burton 1821 – 1890. Sindh, Mecca, Harrar, Tanganyika, Camden’s & the Arabian Nights. https://burtoniana.org/biography/index.html

- Richard Burton (1856) First Footsteps in East Africa or, An Exploration of Harar. https://burtoniana.org/books/1856-First%20Footsteps%20in%20East%20Africa/1856-FirstFootstepsVer2.htm

- Richard Francis Burton (1860) The Lake Region of Central Africa: A Picture of Exploration. New York: Harper and Brothers https://archive.org/details/lakeregionsCent00Burt/page/iv/mode/2up

- John Hanning Speke (1864) Journal of the Discovery of The Source of the Nile. New York: Harper and Brothers. https://archive.org/details/journaldiscover02spekgoog/page/IV/mode/2up

- John Hanning Speke (1864) What Led to the Discovery of The Source of the Nile. London: William Blackwood and Sons https://archive.org/details/whatledtodiscove00spek/page/n9/mode/2up?view=theater

- John H. Speke (1858) A Coasting Voyage from Mombasa to the Pangani River; Visit to Sultan Kimwere; And Progress of the Expedition into the Interior. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London https://archive.org/details/jstor-1798321/page/n1/mode/2up

- Quentin Keynes (1999) The Search for the Source of the Nile: Correspondence between Captain Richard Burton, Captain Jon Speke and others, from Burton’s unpublished East African Letter Book. London: The Cypher Press https://www.cypherpress.com/content/books/burton/burton.pdf

- Christopher Hibbert (1982) Africa Explored : Europeans in the Dark Continent 1769-1889. London: Penguin Books

- Tania Bhattacharyya (2023) Steam and Stokehold: Steamship Labour, Colonial Racecraft and Bombay’s Sidi jamāt https://brill.com/view/journals/hima/31/2/article-p161_7.xml?language=en

- Janet J. Ewald (2000) Crossers of the Sea: Slaves, Freedmen, and other Migrants in the Northwestern Indian Ocean, C.1750 – 1914 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2652435?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Francis Hitchman (1887) Richard F. Burton K.C.M.G. : his early, private and public life with an account of his travels and explorations Vol I. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington https://archive.org/details/richardfburtonkc01hitc/page/n7/mode/2up

- Francis Hitchman (1887) Richard F. Burton K.C.M.G. : his early, private and public life with an account of his travels and explorations Vol II. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington https://archive.org/details/richardfburtonkc02hitc/page/n5/mode/2up?q=bombay

- Thomas John Biginagwa (2012) Historical Archaeology of the 19th Century caravan Trade in North Eastern Tanzania: A Zooarchaeological Perspective. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/2326/1/Dr_Bigi_THESIS.pdf

- A. Le Roy (1884) Souvenirs Africains au Kilima Ndjaro. Paris: https://archive.org/details/aukilimandjaro00lero/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater

- P.P. Baur and A. Le Roy (1899) A Travers Le Zanguebar. Tours: Alfred Mame Et Fils https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6202059x/f13.item.r=.langEN

- Alexander Le Roy (1922) The Religion of the Primitives. Translated by Newton Thompson. New York: The Macmillan Company. https://archive.org/details/religionprimi00lerouoft/page/n5/mode/2up

- Elisée Reclus (1899) Africa and its Inhabitants. London: Virtue and Company. https://archive.org/details/africaitsinhabit02recl/page/n5/mode/2up

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.