In May 1854 Lieutenant Richard Francis Burton arrived in Aden having convinced the Royal Geographical Society to fund an expedition to explore Somaliland with the objective of discovering the upper reaches of the Nile.

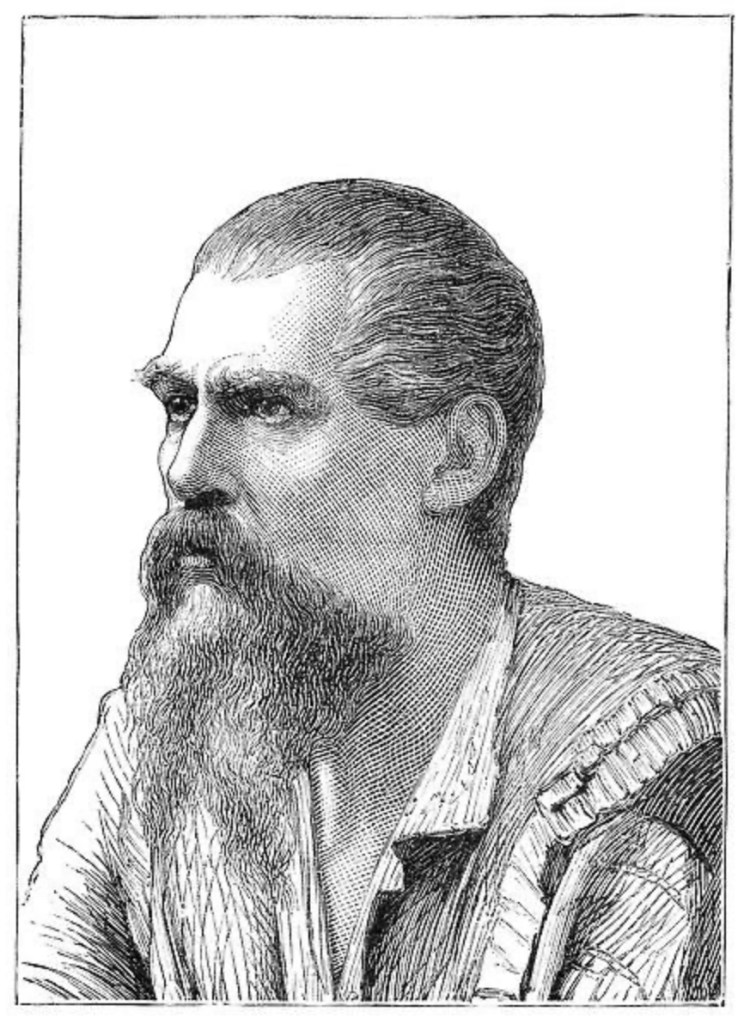

Burton was an officer in the Bombay Infantry of the East India Company, an accomplished geographer, linguist, ethnologist, surveyor and writer who had become a skilful intelligence officer often operating disguised as an Indian.

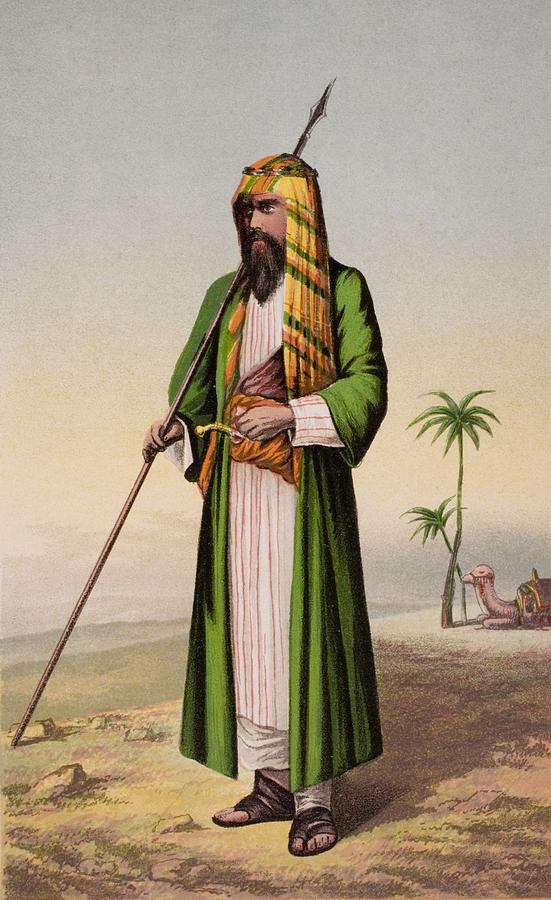

At the age of thirty-three he had already written ethnological studies of the Sindh, mastered half a dozen of the twenty-nine languages he would eventually learn and had travelled in disguise to Mecca and Medina (see right) to document the Hajj.

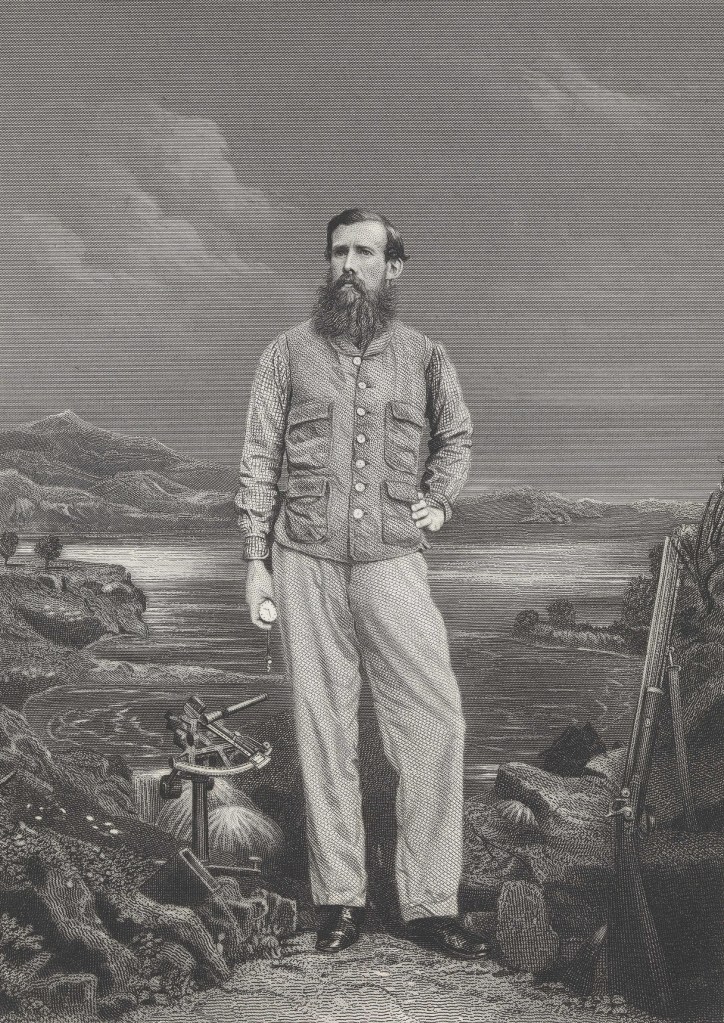

In Aden he was joined by his friend Lieutenant S. E. Herne, Lieutenant William Strain and Lieutenant John Hanning Speke of the Bengal Native Infantry. Speke was just twenty-seven and had fought in several campaigns and battles in India but he considered himself to primarily be a “sportsman”. He was on three years furlough having completed ten years service in India and had arrived in Aden to undertake a hunting expedition.

“My plan was made with a view of collecting the fauna of those regions, to complete and fully develop a museum in my father’s house, a nucleus of which I had already formed from the rich managers of India.”

However, Colonel Sir James Outram, the British Resident refused to grant him permission to travel into the interior. He was advised to attach himself to Burton’s expedition. It was now October, Burton had devised a plan to follow a caravan route south and to eventually reach the coast near Zanzibar but they could not start the main expedition until the following March. In the meantime Burton planned to travel to the mysterious city of Harar, a city in modern day Ethiopia; he sent Lieutenant Herne to Berbera, a port on the Somalian coast and Speke to explore east to Wadi Nagur and to Join the others in Berbera by January 15th of 1855.

Burton had engaged two men to accompany Speke. Sumunter (or Mohammed Sammattar), a Warsangali Arab, was to be his “Abban”, a protector, guide, agent and interpreter, what we might today call a “fixer”. He also was given another Warsangali, Ahmed, who spoke a “smattering of Hindustani and acted as the interpreter between Speke and Sumunter.

Speke then recruited two men of his own: a Hindustani butler named Iman and Farhan, a “Seedi”:

“This latter man was a perfect Hercules in stature, with huge arms and limbs, knit together with largely developed ropy-looking muscles. He had a large head, with small eyes, flabby squat nose, and prominent muzzle filled with sharp-pointed teeth, as if in imitation of a crocodile.

As a boy Farhan had been captured by an Arab ship’s captain somewhere on the Swahili coast so was probably either Swahili or Bantu; Burton later described him as a Negro

“This captain one day seeing him engaged with many other little children playing on the sandy seashore, offered him a handful of fine fruity-looking dates, which proved so tempting to his juvenile taste that he could not resist the proffered bait, and he made a grab at them. The captain’s powerful fingers then fell like a mighty trap on his little closed hand, and he was hurried off to the vessel, where he was employed in the capacity of “powder-monkey.”

Speke describes Héis as “very small. composed, as usual, of square mat huts, all built together, and occupied by a few women.”

He had escaped some years later. It seems likely that he was offering his services as a guard as Speke says he was an ex-soldier and had seen action but unfortunately does not elaborate. Speke’s little expedition finally left Aden in a dhow on 18th October 1854 taking nine days to cross the Gulf of Aden and finally landing at Héis (Heis or Xiis) in the Warsangali Sultanate on the coast of Somaliland.

They tacked east along the coast to Bunder Gori (Las Khorey or Laasgoray) where they had to wait eleven days for the Sultan to grace them with his presence.

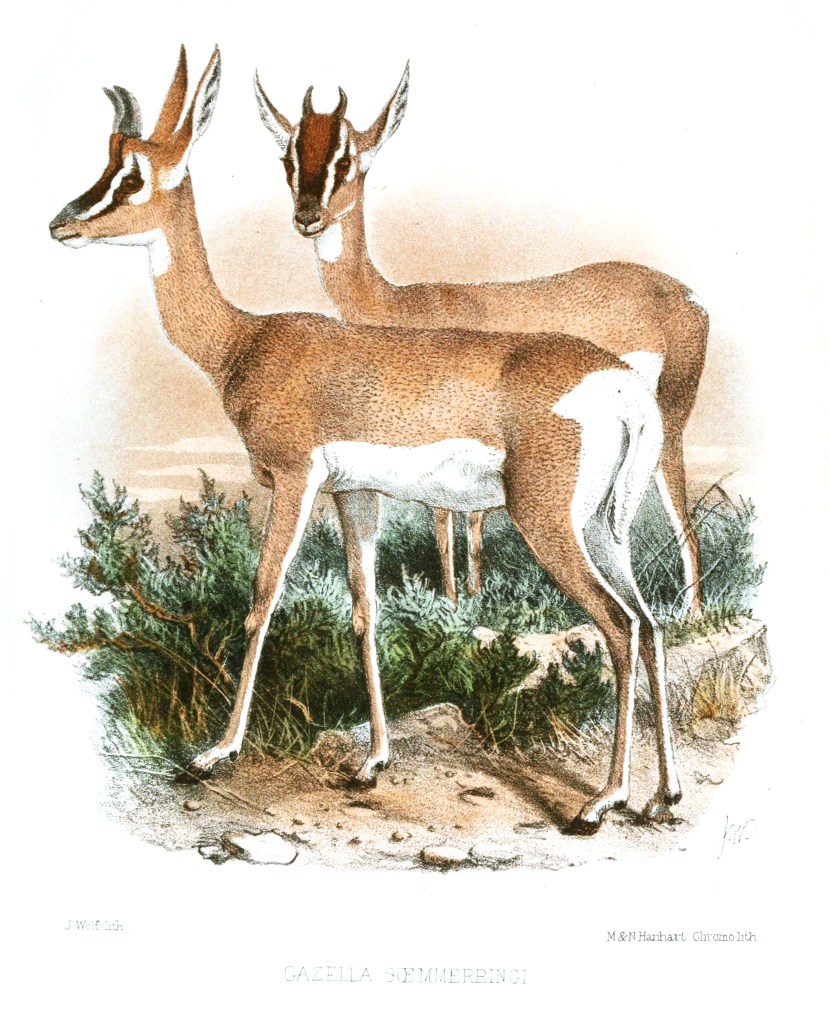

As a so-called “sportsman”, Speke filled in the time slaughtering the local wildlife mentioning the local gazelles (perhaps Soemmerring’s) and Salt’s antelopes.

The Sultan eventually appeared and several more days drifted by as the explorer and the royal party feasted and discussed Speke’s mission.

Speke had been tasked with purchasing camels for the Burton expedition and it appears that he was rather out of his depth and receiving little help from Sumunter, who was of course also a Warsangali, and who had been directly involved in extorting money to buy salt that never materialised. To add insult to injury Farhan reported that Sumunter had tried to bribe him to desert.

Delay followed delay and Speke was only free to move his little expedition when the Sultan believed there were no more gifts or payments to be extracted. Having arrived on the coast in late October, it was early December before they proceeded inland.

There are occasional glimpses into Farhan’s character, he had proved his loyalty back in Gori, but a few weeks into the march we learn that:

“Farhan, ……. delighted at the prospect of showing his skill in any manner – for he styled himself professor of all things.”

By Christmas progress was again stalled in the village where Sumunter’s mother and brother-in-law lived and where Speke learnt that the road to Berbera was blocked by a local conflict. By the end of the year nearly everything he owned in the way of trade goods had been stolen, used as currency or given away.

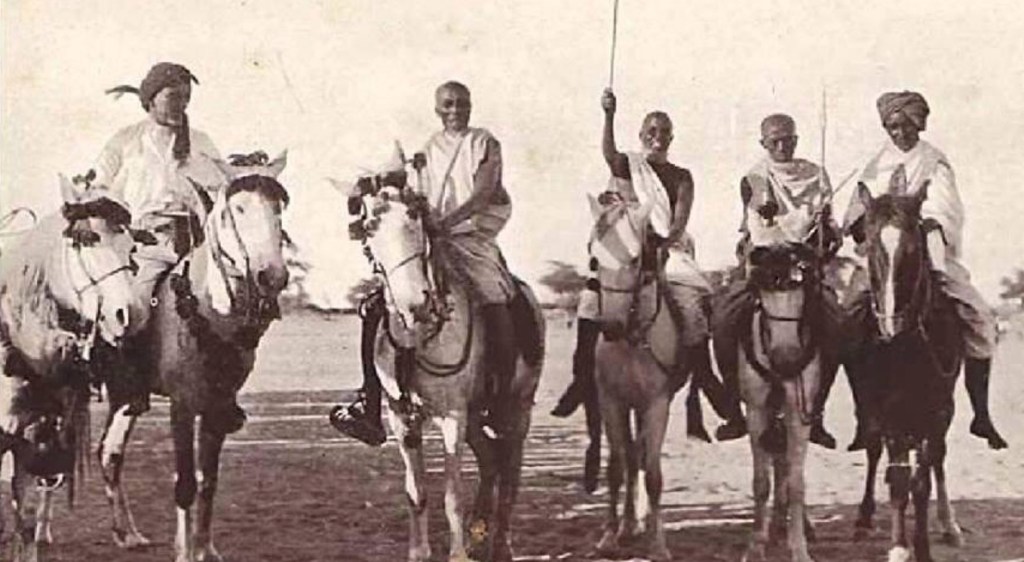

His disputes with Sumunter had reached a critical stage and the local, Dulbahantas tribesmen had turned against him. Sumunter and the other Warsangali loaded the camels and begin to ride away leaving Speke and his servants and a stalwart Farhan surrounded by angry Dulbahantas.

The situation was defused by Sumunter who stopped on the edge of the village to tell Speke that if he would just give some gifts to the Dulbahantas and ask him (Sumunter) nicely to lead them to Berbera they could all get underway.

Handing over his last musket and some other items Speke was miraculously free to go.

Inevitably they got just a few more days along the route before being again delayed; in Speke’s words:

“It would be needless to account all the varied incidents of the next five days that were wasted here, by the thousand and one stories which the Abban produced to fritter away my time near his home, and to swindle me out of my property……….

In final despair I faced about, and marched north-easterly, by a new route, to reach Bunder Gori again, to ship to Aden.”

As they traveled north, at one point they were confronted by robbers who threatened to take the camels. Farhan was in his element and “boisterously” began a war dance while cocking and pointing his gun; as a result the robbers were chased away.

Finally on 15th February 1855 they arrived back in Aden. Sumunter was taken before the Aden Police Court and sentenced to two months imprisonment and fined 200 rupees.

Before leaving Aden Speke recruited a new guide, Mahmud Goolad or El Bayyuz (the Ambassador) who came highly recommenced and who proved to be honest and straightforward. He also recruited a dozen guards of mixed nationalities including Egpytians, Nubians, Arabs and Seedis.

On March 21st 1855 Speke, “Imam the butler”, and “Farhan the gamekeeper”, departed Aden to land at Kurrum (Ras Karrum?) from where they marched to Berbera arriving on 3rd April to be greeted by Herne and Stroyan.

They watched a great caravan prepare to leave for the forbidden city of Harar and a few days later Burton (see right) arrived to a great fanfare.

On April 18th two seemingly unimportant events occurred that probably saved the lives of the expedition leaders. The first event was the arrival of a dhow whose captain they invited to supper; the second was the presence on board of four Somali women who were hoping to get to Harar. Finding the caravan had left they asked to join the expedition and made themselves useful about the camp.

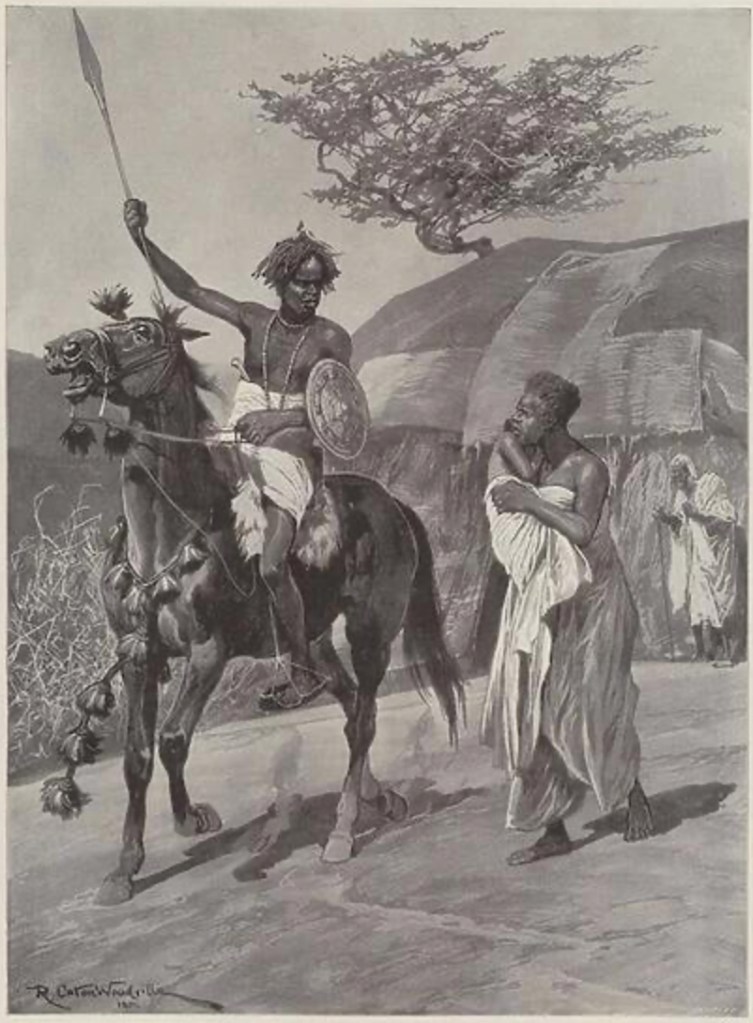

That same evening three horsemen arrived in camp saying they had come to meet the dhow on suspicion that it was part of an invasion fleet intent on taking Berbera.

Unfortunately they were more likely to have been scouts surveying the camp and its defences.

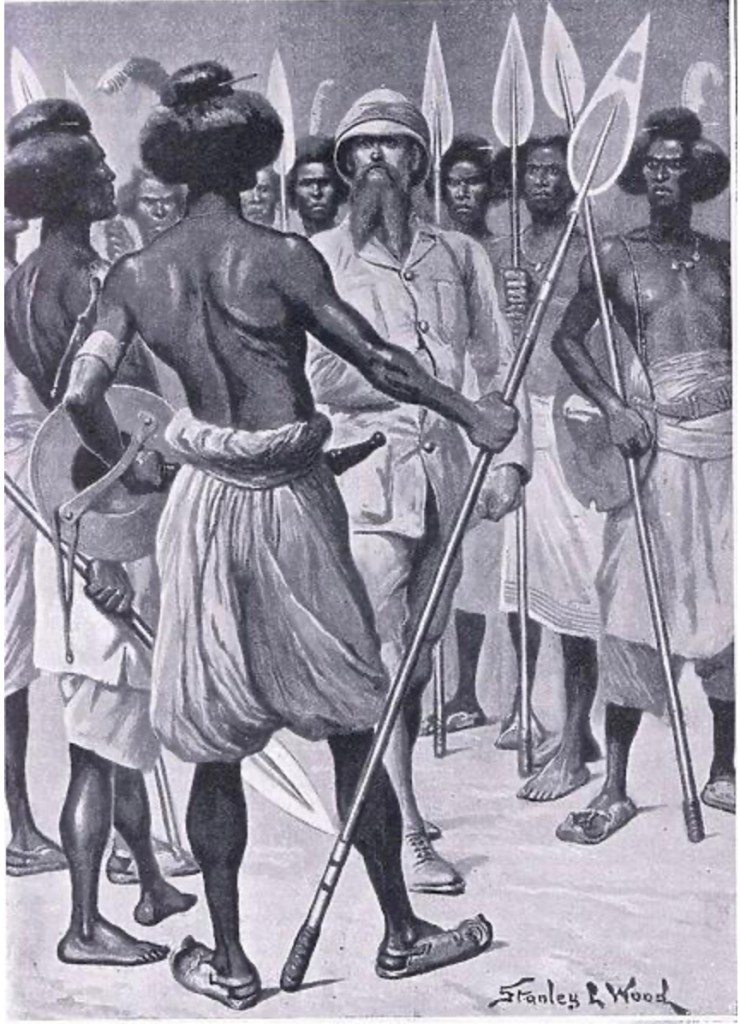

On April 19th at around two in the morning Speke heard gunfire and ran to Burton’s tent to find him loading his pistol. Burton had been woken by El Balyuz and had already sent Herne to hold off a number of attackers at the rear of the camp. Herne soon returned to inform Burton that their servants had run and that “the enemy was in great force”.

The three Englishmen walked towards the attackers firing their pistols; Herne and Burton were in the lead and forced their way through the mob but when Speke’s pistol jammed he was overwhelmed, hit in the chest with a club and forced to the ground. His hands were tied and he found himself being restrained on a lead by a single captor who initially appeared to dissuade others from harming him.

Burton spotted Stroyan’s body on the ground near the camel string and swinging his sabre in front of him he and El Balyuz tried to reach the body, but a thrown spear hit him in the face, entering through his jaw, “knocking out four teeth and splintering the roof of his mouth”. With El Balyuz’s help he joined Herne on the beach. Farhan was sent by either Burton or Herne to ask the dhow to come inshore to take them off

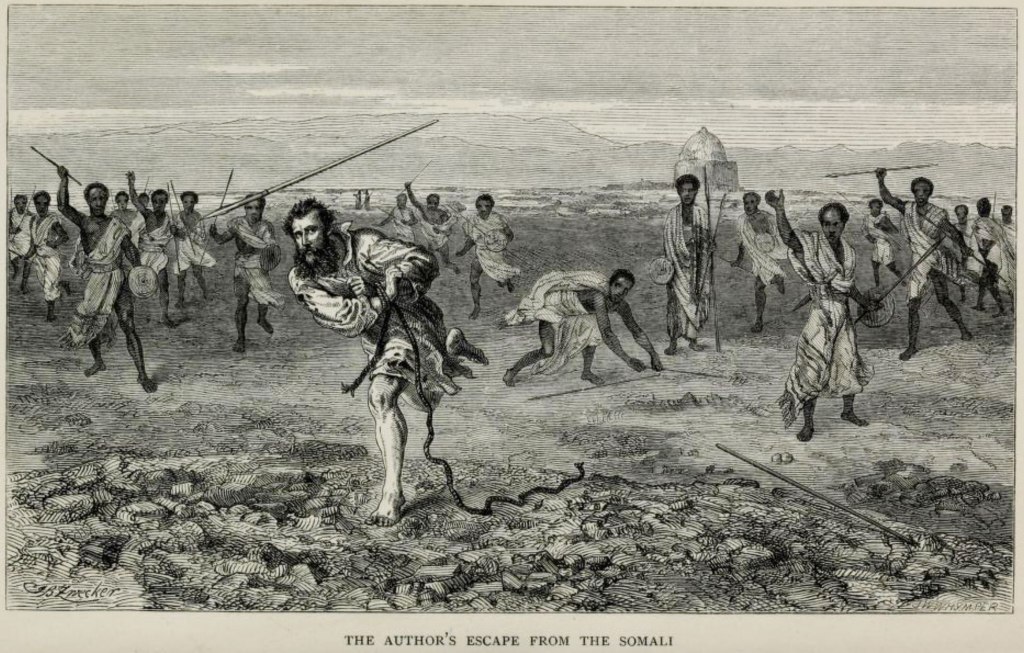

As dawn broke the camp was being looted not just by the original attackers but also by another group who had joined them wanting a share of the spoils. Speke’s captor began to stab him repeatably with a spear and hitting him with his club. Speke was forced to the ground but realising he was about to be killed he managed to get to his feet and land a blow with his, still tied, hands.

Temporarily disorientated the tribesman let go of the rope and Speke made a run for it. He swerved and side-stepped his way through forty men but on reaching the beach he slumped in despair in the realisation that he was still alone and losing a lot of blood.

However, he noticed a group of women beckoning him from some distance away and as he walked towards them he realised they were the four women who had joined the camp on the previous evening. As he neared them El Balyuz appeared with the guards that hadn’t run away.

They boarded the dhow; Burton and Speke were both badly wounded and Stroyan’s body was recovered showing he had been speared through the heart and across his forehead. He was buried at sea the next day. Farhan and four other guards were wounded but, according to Burton, acquitted themselves well. The other seven guards had deserted.

The whole expedition left Berbera and returned to Aden. After recovering from their wounds Burton and Speke found their way to join the British forces engaged in the Crimean war.

Siddi Farhan was paid off in Aden and that is the last we hear of him.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Sources and Further Reading

- The Victorian Royal Navy is an incredible resource for anyone researching the nineteenth-century RN and/ or the slave trade. https://www.pdavis.nl/index.htm

- Rev. Pascoe Grenfell Hill (1844) Fifty Days on Board a Slave Vessel in the Mozambique Channel in April & May 1843. New York: J, Winchester, New World Press https://ia801307.us.archive.org/34/items/fiftydaysonboard1844hill/fiftydaysonboard1844hill.pdf

- Horrors of the Slave trade – The Progresso

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835-1869), 21 September 1843, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singfreepressa18430921-1.2.12.9 - Murder of Lieut. Molesworth The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835-1869), 15 August 1844 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singfreepressa18440815-1.2.6

- British and Foreign State Papers 1843-1844. London: J.Ridgeway and Sons https://archive.org/details/britishforeignst3218grea/page/n5/mode/2up?q=%22cape+of+good+hope%22

- Mrs Fred Egerton (1896) Admiral of the Fleet Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby. London: William Blackwood and Sons https://archive.org/details/cu31924027922479/mode/2up

- South African History Online – the Early Cape Slave Trade https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/early-cape-slave-trade

- Edward A Alpers (1970) The French Slave Trade in East Africa (1721-1810) https://www.jstor.org/stable/4391072?read-now=1&seq=43#page_scan_tab_contents

- Christopher Sanders (1985) Liberated Africans in Cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Gerald S. Graham (1967) Great Britain in the Indian Ocean: A Study of Maritime Enterprise 1810-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press https://archive.org/details/greatbritaininin0000grah/page/n7/mode/2up?q=slave

- A short description of Pascoe Hill’s life – https://www.wikitree.com/genealogy/Hill-Photos-39134/

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle.

- M.D.D. Newitt (1972) Angoche, The Slave Trade and the Portuguese 1844 – 1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/180760?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Brazil: Essays on History and Politics (2018) Britain and Brazil (1808–1914) https://www.jstor.org/stable

- Captain G. L. Sullivan R.N. (1873) Dhow Chasing in Zanzibar Waters and on the Eastern Coast of Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle.

- Peter Collister (1980) The Sulivans and the Slave Trade. London: Rex Collings

- Christopher Saunders (1985) Liberated Africans in cape Colony in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century https://www.jstor.org/stable/217741?seq=1

- Stephane Pradines (2019) From Zanzibar to Kilwa : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Omani Forts in East Africa https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343797763_From_Zanzibar_to_Kilwa_Eighteenth_and_Nineteenth_Century_Omani_Forts_in_East_Africa

- John Broich (2017) Squadron: Ending the African Slave Trade. London & New York: Overlook Duckworth

- Julien Durup The Diaspora of “Liberated African Slaves”!

In South Africa, Aden, India, East Africa, Mauritius, and the Seychelles https://www.blacfoundation.org/pdf/Libafrican.pdf - Philip Howard Colomb (1873) Slave Catching in the Indian Ocean: A Record of Naval Experiences. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Henry Rowley (1866) The Story of the Universities Mission to Central Africa, from its commencement, under Bishop Mackenzie, to its withdrawal from the Zambezi. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. https://archive.org/details/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/mode/2up

- David Livingstone (1865) A Popular Account of Dr. Livingstone’s Expedition to the Zambesi and its Tributies: and the Discovery of Lakes Shirva and Nyassa 1858 – 1864. Accessed at Project Guttenberg’s 2001 edition. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2519/2519-h/2519-h.htm

- Robert Keable (1912) Darkness or Light: Studies in the History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa Illustrating the Theory and Practice of Missions. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://missiology.org.uk/pdf/e-books/keable_robert/darkness-or-light_keable.pdf

- A.E.M. Anderson-Morshead (1899) The History of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa 1859-1898. London: Universities’ Mission to Central Africa https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001117/00001/2x

- E.D Young (1868) The Search After Livingstone, (A diary kept during the investigation of his reported murder). London: Letts Son, and co. The-Search-After-Livingstone

- Sir Henry M Stanley (1872) How I found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures and Discoveries in Central Africa. London: Samson Low, Marston and Company https://archive.org/details/howifoundlivings00stanuoft/howifoundlivings00stanuoft/page/n5/mode/2up?q=wellington

- Fred Morton (1990) Children of Ham: Freed Slaves and Fugitive Slaves on the Kenya Coast 1873 to 1907 https://www.academia.edu/41463426/Slavery_and_Escape_Excerpts_from_Children_of_Ham_Freed_Slaves_and_Fugitive_Slaves_on_the_Kenya_Coast_1873_to_1907

- Horace Waller (1874) The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa. London: John Murray https://archive.org/details/lastjournalsofda01livi/mode/2up?q=chuma

- Mrs. Charles E.B. Russell (1935) General Rigby, Zanzibar and the Slave Trade with Journals, Dispatches, etc. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd https://ia801501.us.archive.org/18/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.34110/2015.34110.General-Rigby-Zanzibay-And-The-Slave-Trade_text.pdf

- Rt. Hon. Sir Bartle Frere (1874) Eastern Africa as a field for missionary labour; four letters to His Grace, the Archbishop of Canterbury. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100371984

- Verne’s Lovett Cameron (1877) Across Africa Vol 1. London: Daldy, Isbister & Co https://archive.org/details/acrossafrica01came/page/n8/mode/1up?view=theater

- Eugene Stock (1899) The History of the Church Missionary Society: its environments, its men and its work https://archive.org/details/historyofchurchm03stoc/page/78/mode/2up?q=jacob

- Donald Simpson (1975) Dark Companions: The African Contribution to the European Exploration of Africa. London: Paul Elek

- Henry Rowley (1866) The Story of the Universities Mission to Central Africa, from its commencement, under Bishop Mackenzie, to its withdrawal from the Zambezi. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. https://archive.org/details/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/ofuniversitstory00rowlrich/mode/2up

- Albert Mwamburi (2024) Bombay Africans; Forgotten Builders of Frere Town Mombasa, 19th Century https://pwanitribune.com/index.php/2023/10/05/bombay-africans-forgotten-builders-of-frere-town-mombasa-19th-century/

- Sir Richard Francis Burton 1821 – 1890. Sindh, Mecca, Harrar, Tanganyika, Camden’s & the Arabian Nights. https://burtoniana.org/biography/index.html

- Richard Burton (1856) First Footsteps in East Africa or, An Exploration of Harar. https://burtoniana.org/books/1856-First%20Footsteps%20in%20East%20Africa/1856-FirstFootstepsVer2.htm

- Richard Francis Burton (1860) The Lake Region of Central Africa: A Picture of Exploration. New York: Harper and Brothers https://archive.org/details/lakeregionsCent00Burt/page/iv/mode/2up

- John Hanning Speke (1864) Journal of the Discovery of The Source of the Nile. New York: Harper and Brothers. https://archive.org/details/journaldiscover02spekgoog/page/IV/mode/2up

- John Hanning Speke (1864) What Led to the Discovery of The Source of the Nile. London: William Blackwood and Sons https://archive.org/details/whatledtodiscove00spek/page/n9/mode/2up?view=theater

- John H. Speke (1858) A Coasting Voyage from Mombasa to the Pangani River; Visit to Sultan Kimwere; And Progress of the Expedition into the Interior. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London https://archive.org/details/jstor-1798321/page/n1/mode/2up

- Quentin Keynes (1999) The Search for the Source of the Nile: Correspondence between Captain Richard Burton, Captain Jon Speke and others, from Burton’s unpublished East African Letter Book. London: The Cypher Press https://www.cypherpress.com/content/books/burton/burton.pdf

- Christopher Hibbert (1982) Africa Explored : Europeans in the Dark Continent 1769-1889. London: Penguin Books

- Tania Bhattacharyya (2023) Steam and Stokehold: Steamship Labour, Colonial Racecraft and Bombay’s Sidi jamāt https://brill.com/view/journals/hima/31/2/article-p161_7.xml?language=en

- Janet J. Ewald (2000) Crossers of the Sea: Slaves, Freedmen, and other Migrants in the Northwestern Indian Ocean, C.1750 – 1914 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2652435?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Francis Hitchman (1887) Richard F. Burton K.C.M.G. : his early, private and public life with an account of his travels and explorations Vol I. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington https://archive.org/details/richardfburtonkc01hitc/page/n7/mode/2up

- Francis Hitchman (1887) Richard F. Burton K.C.M.G. : his early, private and public life with an account of his travels and explorations Vol II. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington https://archive.org/details/richardfburtonkc02hitc/page/n5/mode/2up?q=bombay

- Thomas John Biginagwa (2012) Historical Archaeology of the 19th Century caravan Trade in North Eastern Tanzania: A Zooarchaeological Perspective. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/2326/1/Dr_Bigi_THESIS.pdf

- A. Le Roy (1884) Souvenirs Africains au Kilima Ndjaro. Paris: https://archive.org/details/aukilimandjaro00lero/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater

- P.P. Baur and A. Le Roy (1899) A Travers Le Zanguebar. Tours: Alfred Mame Et Fils https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6202059x/f13.item.r=.langEN

- Alexander Le Roy (1922) The Religion of the Primitives. Translated by Newton Thompson. New York: The Macmillan Company. https://archive.org/details/religionprimi00lerouoft/page/n5/mode/2up

- Elisée Reclus (1899) Africa and its Inhabitants. London: Virtue and Company. https://archive.org/details/africaitsinhabit02recl/page/n5/mode/2up

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.