Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

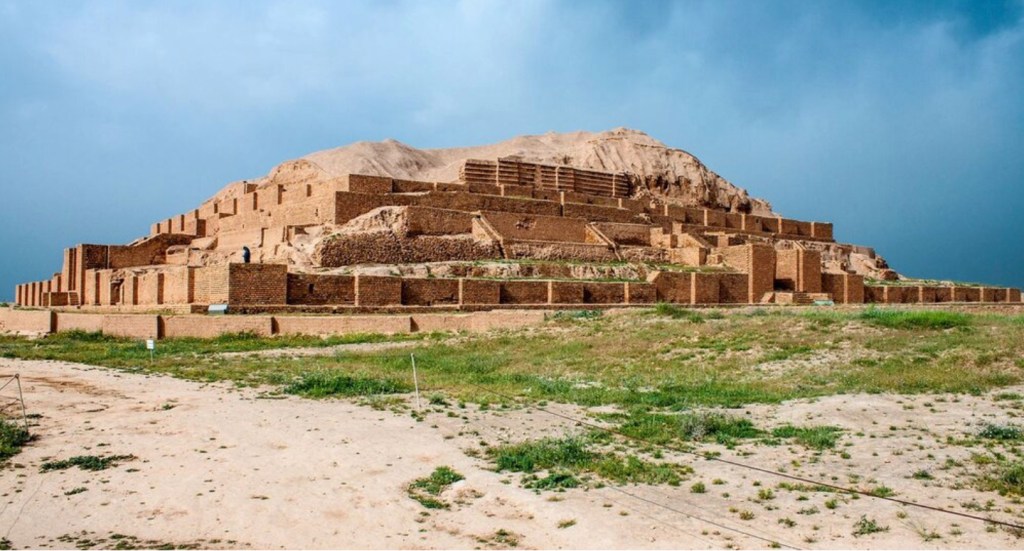

The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550 to 330 BC)

Every nationality has a particular, often narrow and culturally filtered, view of history. When I was at school in the 1950s and 60s Latin was firmly on the curriculum and ancient Greek was an optional after school class; history lessons started in classical Athens and quickly progressed to the Romans who conveniently invaded Britain where history stayed firmly rooted apart from occasional forays into Europe along with various medieval kings.

As a result whole swathes of the world were just ignored, including the Achaemenid Persian Empire whose only appearance in my school days was as the bad guys at Thermopylae and Salamis but who got their comeuppance when Alexander conquered them.

The Achaemenid Persian Empire, expanded through conquest, from the Persian Gulf around 560 BC until by 486 BC, it included around 5.5 million km2 as shown in the map above. An empire ruling over around 50 million people, which was 44% of the population of the world in around 480 BC. 3 It remained unsurpassed for its geographical scale until 1,700 years later when the Mongolian Empire ruled most of Asia.

The Persian Empire was advanced, sophisticated, well organised and rich but given the wide range of peoples it embraced it was also culturally diverse and complex with many regional variations. However, there were some common threads throughout the empire.

The economy was underpinned by agriculture carried out on a mixture of peasant-owned small farms and large estates in the hands of the royal family, the nobility and military leaders who collectively formed the ruling class. Some trade and industry was in private hands but many workshops were on royal or elite estates. Merchants benefited from empire-wide legal, administrative and financial systems and a common currency.

In the 5th century BC Babylonian documents refer to household slaves and workers in the homes of the royal family and the nobility. They were collectively referred to as kurtaš; the overwhelming majority were foreigners and many were probably enslaved prisoners of war. The meaning of kurtaš is therefore unclear, it may have started as meaning “household slave” and evolved into the more generic “worker”. 5

As new regions and towns came under Persian rule and the size and number of the estates owned by the elites grew “hostage” men, women and their children, also often referred to as kurtaš but, at other times as douloi (slaves), were taken and relocated across the empire to work on the estates of the elite. This was a period of a more intensified utilisation of foreign workers of whom some were semi-free people settled on royal land but others were undoubtably slaves.

Contemporary Greek writers offer a picture of these mass deportations carried out by the Persians associated with military activity. Whole families were forcibly relocated to the estates of the elite or to work on major state sponsored construction sites and irrigation projects in different parts of the Persian Empire. Their status is unclear but whether they were slaves or being forced into some form of serfdom is rather a moot point; they were owned, exploited and dependant upon rations being issued by the authorities. 6

In 526 BC The Persian Great King Cambyses II (see right) took the Egyptian pharaoh, Psamtik III and 6,000 captive Egyptians to Susa before declaring himself pharaoh the following year.

The 6,000 were put to work on state construction projects.

Herodotus, the Greek historian, gives a further example of people being enslaved by the Persians from Greek polis (city state) of Barca and being re-settled in Bactria in a village that they renamed Barca in memory of their origins. To Herodotus’ knowledge they were there for at least 60 years working on the royal estate.

The women and children of Ionian Miletus, another Greek polis, were deported to Persia, and it is possible, based on the Persian’s address to the Ionians that the boys were destined for castration and the girls to be taken to Bactria.

Using classical writers as his source Miroslave Izdimirski 7 provides many more examples of mass deportations from towns and cities taken by the Persians or who had rebelled against them. Often the captives were women and children, the men having been killed in battle or executed; in many cases they were taken to Susa and then distributed by the king across the agricultural estates or mining operations owned by the ruling elite.

Herodotus tells the story that Darius I (see left) was encouraged to invade Greece by his wife, Queen Atossa, who was keen to possess some Greek slaves as handmaidens.

This may just be a story to show the king as weak and influenced by women, something a strong Greek man would never let happen, but it does underline that slaves were not just taken in war but were a purpose for war. 9

It is clear that the Achaemenid Persian Empire, if not dependent upon slavery, was using enslaved prisoners of war and rebels in large numbers to support the growth of their economy as the empire expanded. Recent historians have suggested that the role of slavery has consistently been underestimated in the Persian Empire.

Muhammad Dandamaev estimates:

“……. that slaves may have constituted between a quarter and a third of the population of Babylonia under the Persian Empire; in terms of its social location, many households owned a few slaves, with wealthier families owning dozens and sometimes hundreds, and the Royal household owning considerably more.” 10

Classical Greece (510 to 323 BC)

The Classical Age of Greece is the period between the end of the Persian Wars in 479 BC when the Greeks defeated the Persians at the Battle of Salamis and the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC.

Greece was the birthplace of western civilisation, the mother of democracy, philosophy, medicine and scientific theory. The region where architecture and the arts reached such new heights that the classic Greek style became the model for many later societies. Greek philosophers, statesmen, artists, scientists and mathematicians debated, theorised and formalised ideas that have stood the test of time.

Given that the economies of the loose collection of culturally and linguistically related city states that made up the Hellenic world were predominantly agricultural, how could elite Spartan men be full time warriors; how did Plato, Socrates, Aristotle et al find time to think, debate and teach; why were they not tending sheep, tilling fields, treading grapes or picking olives?

The simple answer is that Greek society was utterly dependant on slaves. Slaves worked much, maybe most, of the land in Attica, probably all of it in Sparta, mined the silver that paid for the Athenian fleet, worked and often ran businesses, acted as business agents and traders for their masters and worked in nearly every household as well as fulfilling the roles of concubines, musicians, dancers and prostitutes.

It is often said that coal powered the British industrial revolution; in classical Greece slaves powered the economy that created the “leisure” time needed to bring about the achievements the ancient Greeks are remembered for.

However, it is easy to fall into the trap of treating classical Greece as if it is a federated state, a “country” where, give or take a few regional differences, society operated in a particular and singular manner. This is far from the truth. Classical Greece was a geographical region not a political entity with over 1,000 “polis” or city states varying in size from small towns to cities although the cities were small by modern standards. Each polis had a hinterland of farms to sustain the population, its own laws and form of government.

To consider slavery in classical Greece it is interesting to focus on just two, contrasting, city states:

Coastal Athens, the most populated of the classical city states, a fledgling democracy and the home of great artists, architects, writers, historians and philosophers who are still remembered today.

(Left: a Roman copy of a bust of Pericles (495 – 429 BC), an Athenian politician and general, originally found in Lesbos. British Museum) 11

And, landlocked Sparta, the largest city state by territory, their great opponents, an insular, conservative society; ruled by two kings and an oligarchy, who oversaw a highly militaristic state where all Spartan men trained and served as warriors from the age of 7 until they were 60.

(Left: a bust of a Spartan warrior, usually referred to as Leonidas who was King of Sparta in 480 BC. Museum of Sparti.) 12

Athens

The Good Life

Classical Athens is often described as an ideal society where its citizens could meet in the agora 13 in the mornings to conduct business and later in the day, at the gymnasium and public baths to exercise, socialise and play games including marbles, dice and an early form of backgammon.

Philosophy, politics and the arts would often have been the topic of both casual and group discussions in either place and the great philosophers of the time have been remembered, quoted and have provided the basis for modern political thinking for nearly 2,500 years.

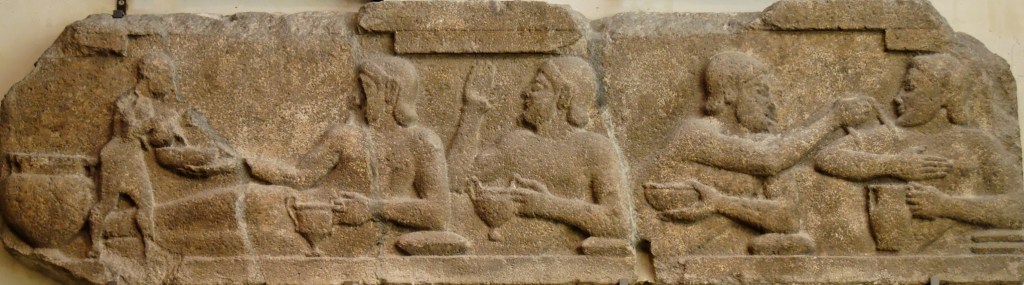

An Athenian could visit one of the many temples in the city to ask favours of the gods and later in the day meet friends at a sumposion (symposium) or drinking party, to enjoy fine dining, music and philosophical discussion; although such gatherings often descended into heavy drinking and sex with the hired entertainers and prostitutes hired for the occasion.

In March and April Athenians could attend a five-day festival of drama at the Theatre of Dionysus on the slopes of the Acropolis where three dramatists would compete against other for prizes by presenting four new plays including three tragedies and a bawdy satyr.

This idyllic lifestyle was pursued in the pleasant climate of the Eastern Mediterranean in a city famous for its beautiful architecture and favourable location sheltered by mountains and just a short distance from its harbour at Piraeus. Here, a new form of political system, democracy, gave male citizens a previously unheard of say in the running of their city.

Athenian Aristocracy

However, only a small proportion of people, perhaps just 10% of male citizens, were wealthy enough to enjoy this lifestyle to the full. They were, in effect, an aristocratic class, wearing distinctive and expensive clothing, hunting, engaging in horse and chariot racing, meeting wealthy friends for evenings of heavy drinking and joining elite cavalry regiments instead of serving on foot as hoplites, armed infantrymen, like other young citizens.

However, because of their wealth, they were often obliged to pay special taxes and undertake public services or sponsor state projects. 19 It is intriguing that the classical Athens society that we know best was the world of a small minority, a few thousand men out of the whole population.

Population and Slave Ownership

It is impossible to present definitive numbers regarding the population of any ancient city but it is generally accepted that, at the height of its powers in 431 BC, the total population of Athens, including rural Attica, was around 300,000.

Of these 160,000 were citizens 20 made up of 40,000 men, 40,000 women and 80,000 children. Of the remaining 140,000 people it is thought that 25,000 were metics, free foreign residents, and 120,000 were slaves. 21

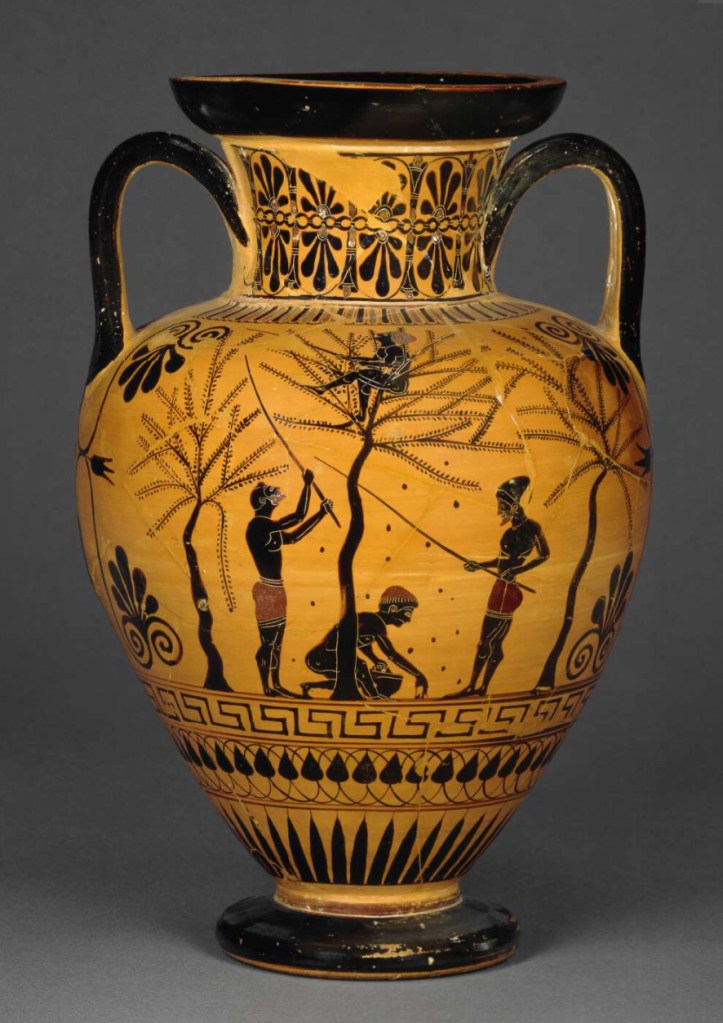

The Athenian economy in the classical era was underpinned by agriculture .

The land was owned by one of three entities: the state, who leased publicly owned farms to citizens and metics; the wealthy elite citizens whose farms were operated with slave labour and a large number of citizen farmers.

(Olive picking. Attic black-figured neck-amphora, ca. 520 BC) 22

The non-elite citizen farmers ranged from people just below the elite in terms of wealth to subsistence farmers eking out a living on the rocky soil of Attica. Other than on the farms of the very poorest citizens the agricultural workers were predominantly slaves.

On average wealthy Athenians owned around 10 slaves and slave ownership probably extended to at least a third of all citizens, although many would only own a single slave or a very small number. There were exceptions to these averages including workshops employing tens and mines employing thousands of slaves. Many slaves would have worked in households undertaking all the labour intensive duties that freed their owners to play a role in Athenian society.

To understand slavery in Athens we need to keep in mind that all male citizens probably aspired to partake in all or part of the lifestyle enjoyed by the wealthy elite; he took no pleasure in work and to have worked for a wage would have been tantamount to being a slave. As a result, he had to confront the paradox of not working, or working very little, yet having enough money to enjoy a life of leisure and maintain or elevate his place in society.

One way to achieve this and to supplement any income from their land, was by training a commercially astute slave to become a trader or to act as a business agent on their behalf. Citizens set up slaves in small businesses that were then left to the slave to manage and run, usually in a quite independent manner.

Slave Roles and Occupations

There were slaves employed as farmers, traders, artisans, barbers, masseurs, hairdressers, shop assistants and even bankers 24 who were often financially rewarded by their masters and in time might afford to buy themselves out of slavery. In time of war citizen warriors, hoplites, took at least one slave with them to care for their weapons and to help them arm for battle like a medieval squire or a twentieth century batman.

Another strategy was to own slaves that were then rented out to other people who either could not afford their own slaves or who needed short term labour. The state-owned but privately operated silver mines at Laureion were fundamental to the economy of Athens and to the city’s security; silver from here funded the fleet that overcame the Persians at Salamis. The mines were worked by as many as 20,000 slaves, including child miners, and many would have been rented to the mine operators. Owning these slaves could yield a return of 30% on the original purchase so the income on a slave lasting more than three years was pure profit. 26

State owned slaves were employed as clerks and bureaucrats and the playwright Aristophanes alludes to a “police force” of 300 enslaved Scythian archers who worked under direction of the city magistrates.

(Left: a red-figure vase painting of a “Scythian archer”) 27

The breadth of roles carried out by public slaves is remarkable and included the public executioner, prison guards, the workers in the state mint, the keeper of the inventory of the Chalkotheke, the treasury on the Acropolis, and the ‘auditors” checking the quality and authenticity of coins in circulation. 28

The final sector of society in which slaves commonly worked were the entertainment and sex industries which were often one and the same; slave singers, musicians and dancers were expected to provide sexual favours as part of an evening’s entertainment.

(Kylix with a Prostitute Preparing to Bathe – Attica 480 BC) 29

The city was well supplied with brothels and prostitutes. Concubinage was common and, as with all slave societies, masters exploited their female slaves.

Given their role in nearly every economic activity it is not difficult to see why nearly half the population of classical Athens were slaves but it does raise the question of where did they all come from?

The Source of Slaves

As early as the 6th century BC Athens developed laws that prohibited debt slavery and there is no record of citizens being enslaved as punishment for crimes. As a result, most slaves in Athens were foreigners but “foreign” included Greeks taken in war from other city states. The children of slaves were slaves but Athenian households were small and relationships between slaves of different households is unlikely to have been common in the city but perhaps more often occurring at the mines or in rural farming areas.

Athens, was connected by trade routes across the whole eastern mediterranean and regularly acquired slaves from Asia Minor (Anatolia, modern-day Turkey), the Levant (modern-day Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel), Thrace (southeast Europe from southern Bulgaria to the Bosporus), regions along the upper reaches of the Danube (from the Black Forest in Germany to the Carpathian mountains in Slovakia), and all around the Black Sea. There is some evidence of African slaves, such as Ethiopians, being highly valued because of their rarity.

David Lewis 31 who has researched this subject in great detail believes that the Thracians may have been the largest ethnic group but with Phrygians (central Turkey), Carians (southwest Turkey on the Aegean opposite Kos and Rhodes), and Syrians in large numbers. This shows that the majority of slaves in Athens came from inside the Persian Empire. Some were acquired through raiding, Xenophon tells of a raid in northern Lydia where the Athenians captured 200 slaves, but it is likely that most were purchased at coastal markets on the fringe of the Persian Empire.

Less frequently, Greek slaves were taken in wars against other Greek city states. For example Athens besieged the island city of Melos in the Cyclades in 416 BC and on its surrender executed “as many men as they captured” and enslaved the women and children. 32

Whatever their source slaves were brought to market in Piraeus within days of having being captured or purchased. Because the sailing distances in the eastern Mediterranean are comparatively short there was no need for specially equipped slave ships; slaves could be carried on the decks of tasting vessels.

Conclusion and What if?

There is evidence to suggest that slaves in classical Athens cost much the same as the annual salary of a skilled craftsman which is less than in other ancient societies such as Rome or Mesopotamia. 33 For the owners of farms, mines, shops, brothels or the small-scale industries that existed in classical Athens slave ownership clearly made economic sense.

As we have seen not all Athenian citizens were wealthy, many would have been subsistence farmers but most historians believe that, even if they worked alongside them in the fields, most poor farmers owned a slave. This depth of ownership may be unique in any ancient society.

Slavery was imbedded deeply in Athenian society allowing it to function at the most fundamental level; without it, Athens could never have produced its great philosophers, architects, poets and playwrights, they would have all still been eking out a living on the rocky soils of Attica.

Nor, is it likely they would have built an Empire or even survived as a city state as the silver to finally defeat the Persians at the Battle of Salamis was mined and turned into coinage by 10,000 slaves and no doubt slaves built the ships the money purchased. If that battle had been lost Athens, Sparta and all the other city states would eventually have been absorbed into the Persian Empire; no Alexander the Great, no Ptolemaic Egypt and maybe no Roman Empire.

Sparta

Origins

Sparta and Athens had little in common, chalk and cheese with their contrasting political systems and a fundamentally different approach to just about everything in their societies.

Athenians believed they were descended from the indigenous tribes of Attica who had sprung from the soil as children of the earth goddess Gaia. This origin myth supported their self proclaimed racial superiority over foreigners, including Greeks who had descended from invaders such as the Spartans, who were believed to have descended from the Dorians who allegedly invaded Greece around 950 BC.

There is no archaeological evidence to support a Dorian invasion but wherever the Spartans came from or whether they were the remnants of the Mycenaean age population that had been all but destroyed by an earthquake in around 1200 BC they had conquered Laconia on the Peloponnese by around 950 BC and by 700 BC had expanded to dominate neighbouring Messenia to create the largest classical age polis.

By 650 BC the Spartan army was the most powerful land force in Greece and remained so until it was defeated by the Thebians at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC.

Above: A fully armoured warrior wearing a Corinthian- type helmet, a cuirass and short tunic, a wristband and an armband on his right arm, and greaves. As is usual on figurines of this type, the warrior held a shield, its grip only partly preserved on his forearm and a spear in his right hand. 35

Spartiates

Another significant contrast between classical Athens and Sparta is the abundance of contemporary literature describing Athenian society written by the Athenians themselves and the scarcity of contemporary documents written by Spartans.

To further muddy the waters much of what we do know about Sparta was written by their arch-rivals the Athenians so, given their mutual animosity, it has to be taken with a pinch of salt. Athenian writers promote the view that Sparta was an illiterate society focused only on military training but recent studies have proved this to be a fallacy.

Ellen Millender concludes her study of literacy in Sparta by warning against:

“…… resorting to the easy and all too common stereotype of Sparta as a society whose political structure naturally bred hostility to the written word.

As a society which focussed on war, discouraged individuality, and put a premium on the total integration of its members into the state, Sparta did not promote the fill alphabetic literacy that blossomed in fourth-century Athens.

Nevertheless, the Lacedaemonians’ frequent and skilful conduct of war and diplomacy made the written word a necessary tool for full Spartiate citizens.” 37

So, taking Millender’s warning to heart I will endeavour not to resort to the stereotypical descriptions of Spartan society.

We do know they had a rigid social structure with Spartiates, as the elite class; like the Athenians they maintained racial purity by insisting that a Spartiate was born to two Spartan parents.

At the age of seven Spartan boys were taken from their parents and placed into the educational system, agoge , which was preparation for military service but where they probably also learnt reading, writing and some level of mathematics, all of which were useful skills for an elite warrior. They lived in communal age groups which were no doubt highly competitive environments and toughened up though military and physical training.

At the age of 30 men who had completed their agoge education became full citizens but they continued to live in barracks in a mess made up of their peers.

They now had full rights as a citizen but remained soldiers until too old to fight at the age of 60.

Spartiate men and boys made up a small percentage of the population of the polis, perhaps 10% to 30%

Left: a Spartan officer in bronze from c. 500 BC.

Perioikoi

In addition to the Spartiates there was another significant group of freemen and women, the Perioikoi, a word meaning “those who dwell around”.

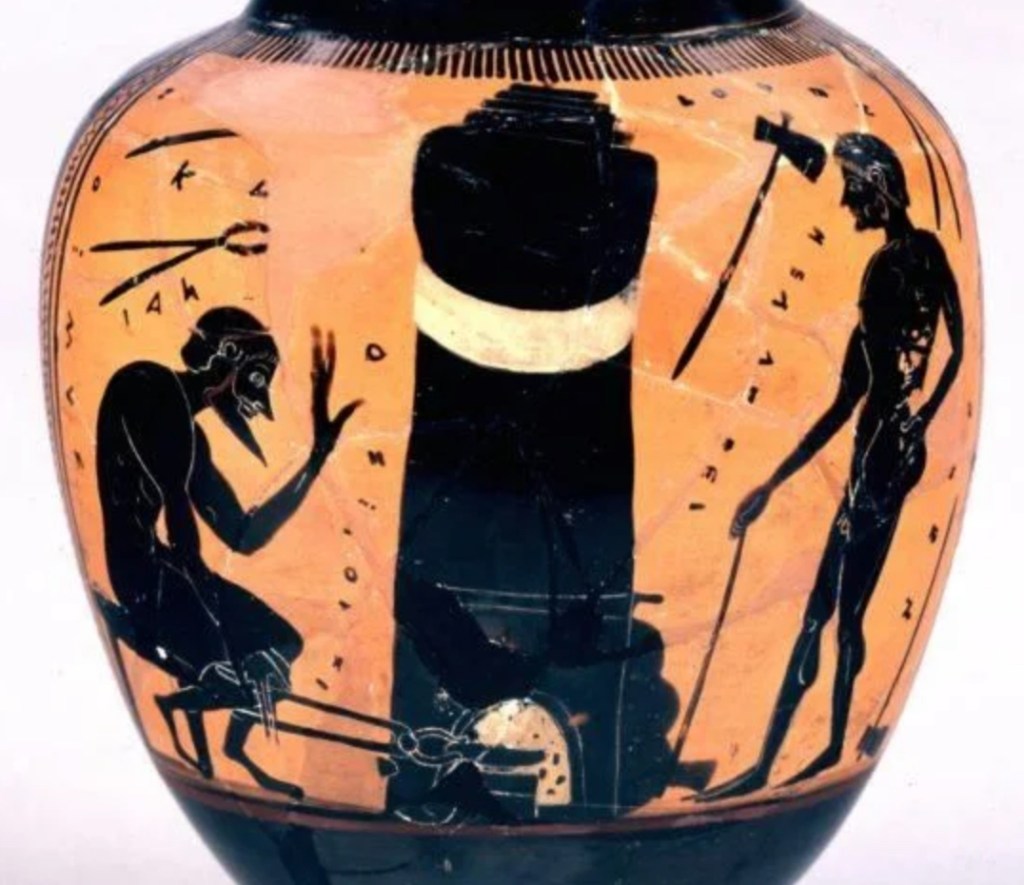

Left: Athenian wine jug depicting a metal workshop with two men at a furnace. 500–475 BC 39

The Perioikoi are only mentioned in passing in contemporary sources and usually in a military context as they served, and appeared to play a vital role, in the Spartan army.

Silva argues

“…….that perioikoi were indistinguishable from the Spartans in battle. In all probability, they trained in a similar fashion, dressed in a similar fashion and fought in a similar fashion. As Lacedaemonians in the Lacedaemonian army, the perioikoi could not afford to be second-rank soldiers, and the evidence ultimately shows that they were not.” 40

Beyond their contribution to the military the role of the Perioikoi is a little mysterious. The Spartiates were barred from any commercial enterprise so the conventional view has been that the Perioikoi were artisans engaged across the wide range of crafts necessary for daily life, everything from potters to blacksmiths.

Sparta was rich in natural resources, including; marble, iron ore, lead and gold and it seems likely that the Perioikoi dominated the processing of these raw materials as well as the manufacture of clothes and footwear.

Ridley argues that if the Spartiates could not engage in industry then the only people they could trust to make and maintain their weapons were the free Perioikoi who, as we have already seen, served in the army alongside the elite Spartans. 42

Right: Bronze helmet of Corinthian type in the British Museum 43

Helots

Which leaves the third tier of Spartan society, the Helots. Since classical times there has been differing options of whether we should consider helots as slaves. There seems to be general agreement that they were the original inhabitants of Laconia and Messenia who were conquered, or otherwise were absorbed into, the Sparta state by 700 BC.

We know frustratingly little about the Helots partly because the Spartans left few accounts of themselves, so our information comes from outsiders observing a notoriously secretive society and partly because slaves were too common, too much part of the background of every day life to be mentioned at all.

It appears generally accepted that Helots were tied to the land, possibly as share croppers, solely responsible for farming a small holding and handing over a proportion of their crop to the state. This seems a likely model if we accept that the Spartiates were dedicated to their military training and the Perioikoi were predominantly craftsmen. There was obvious management structure to supervise the Helot farmers on a day-to-day basis.

The question that has troubled writers and historians since classical times is how many Helots were there and what percentage of Spartan society did they represent.

The excellent collection of essays on the Helots edited by Nina Luraghi and Susan Alcock in 2003 is a comprehensive and up-to-date source on these enslaved people. 47 Within those essays, and supported by detailed arguments based on land use and agricultural output, Thomas Figueira comes to the conclusion that in around 480 BC the Helot population was between 75,000 to 118,000 or about 3 to 5 times the number of Spartiates.

The second question that historians have debated is whether Helots were slaves or suffered some other form of servitude such as serfdom. Having spent a considerable amount of time researching the east African slave trade I flinch as soon as a writer begins to argue that there is a form of slavery that is less horrible, less degrading and therefore somehow “excusable”.

To repeat something discussed earlier Lenski and Cameron 49 define slavery as:

“…. the enduring, violent domination of natally alienated 50 and inherently dishonoured individuals (slaves) that are controlled by owners (masters) who are permitted in their social context to use and enjoy, sell and exchange, and abuse and destroy them as property.”

A comparatively tight definition that incorporates the ideas that:

- Slavery is an institution that endures over multiple generations of slaves:

- The slave is dishonoured, i.e. has any social standing denied to them;

- The master is the absolute owner of the slave as property and the sole beneficiary of the slave’s labour.;

- And, it also alludes, by mentioning natal alienation that, across history, the slave is typically “other”, a person taken from elsewhere, or bred from people taken from elsewhere.

Helots meet each of these components of the overall definition.

Their enslavement lasted from as early as 700 BC until, in the case of the Messenian helots, 370 BC and the Laconians as late as the 2nd century BC.

They were without doubt dishonoured and denied any social standing in Spartan society and whilst they may have had social standing within their own communities that is irrelevant.

Some writers have argued that to be enslaved a person must be owned by an individual. There is no obvious distinction between the master as an individual and the master as a state. The status and experience of the slave is not dependent on that factor of ownership. It is true that they could not be brought and sold but in the context of an entire indigenous race being enslaved and state owned this point seems irrelevant.

Finally the slave the idea that the slave is typically “other” and suffers natal alienation is less clear for the Helots who are assumed to been enslaved in their own lands but, by not being of Spartan blood, they were ethnically different and treated not just as “others” but as an inferior race. We cannot know whether they retained any of their original culture or beliefs.

Conclussion

In classical Athens the elite, having put a short period of military service behind them, had, and the non-elite citizen aspired to, a life style of philosophical and political debate, exercise and athletics, time to appreciate the arts and evenings of fine dining, drinking and sex. They delegated earning a living to slaves and were clothed, bathed, fed and serviced in every way by more slaves. 120,000 slaves made 80.000 adult citizen’s lives as pleasant as possible.

In Sparta the elite citizens played no part in industry and agriculture, they spent their time keeping fit and training as warriors to the exclusion of all else. They relied on large number of slaves to provide their food and wine, and, one might assume, mine the minerals from which their weapons were made. There were, as many as 118,000 slaves, helots, 3 to 5 times as many as there were Spartan citizens.

Two city states existing contemperaneously just 200 kms apart with radically different cultures but with societies organised around their elite citizens having no need to contribute to, what were still primarily agricultural, economies. Athens made this possible by harvesting prisoners of war and purchasing slaves from the Near East. Sparta achieved the same objective by enslaving the populations of the regions they conquered.

To be continued ………..

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.