- Introduction

- Being Owned

- Being Sold

- Living Conditions

- Being Freed

- Retirement

- Markets and Traders

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

Being Owned

A slave was property, a possession no different than any of the other items a Roman citizen had inherited or purchased.

The little plate to the left was found in Rome and dates to the 4th century AD. It was designed to be attached to metal collar and is similar in concept to the tag on a pet dog with the owner’s phone number or post code.

That analogy perfectly describes the relationship between master and slave.

The tag, which is 5.8 cm in diameter, so much bigger than a dog tag, says:

“Tene me ne fugia(m) et revoca me ad dom(i)num Viventium in ar(e)a Callisti“

“Hold me, lest I flee, and return me to my master Viventius on the estate of Callistus” 1

It is probable that the slave wearing this collar and tag had previously tried to escape but collars and tags like this are frequently found across Rome and in North Africa. It is possible that the practice developed after the Emperor Constantine banned the practice of tattooing the forehead of slaves with details of their ownership.

Harder to interpret is a gold bracelet in the form of a coiled snake that was found on the body of a woman at Moregine, a settlement near Pompeii that was also destroyed in the eruption. It is inscribed inside with the words Dominus ancillae sure, from the master to his slave girl. Was this a man infatuated with his slave and were those feelings reciprocated or was she a freedwomen wearing her patron’s expensive gift?

Anyone looking to find excuses for slavery in Rome should consider that there is no evidence that the Romans ever seriously questioned the institution of slavery nor did they make any attempt to restrict it until the role of slavery in the economy began to decline in the Eastern Roman Empire after the Western Empire collapsed in 476 AD. And, even then, it was replaced by coloni or serfs which were slaves in all but name.

Punishment

Slaves were often treated with great brutality, flogging a slave appears to have been common practice along with branding and even the breaking of bones or eye-gouging as punishments.

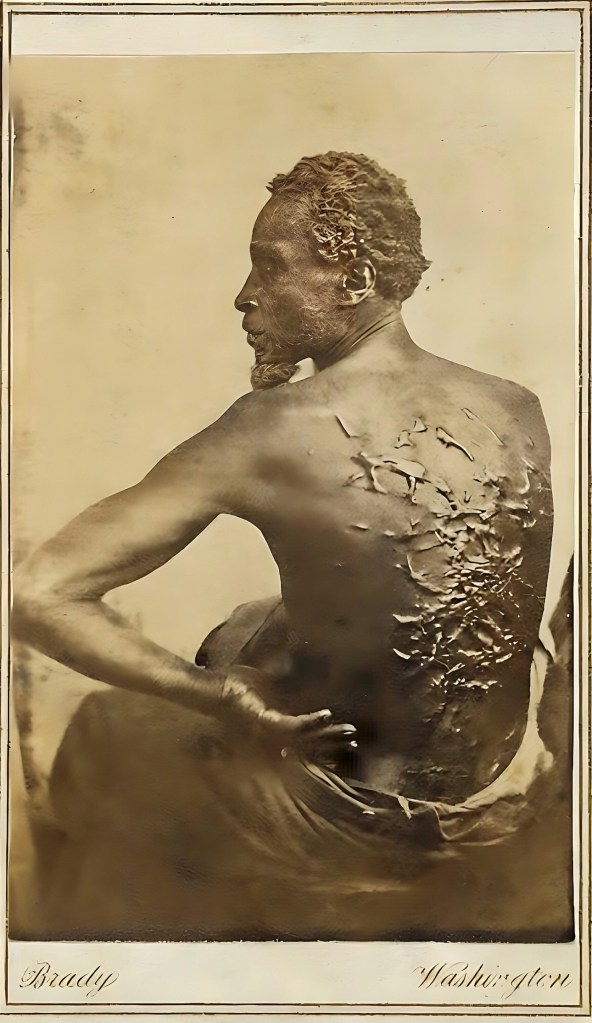

There are no mosaics or sculptures showing the effect of flogging in Rome but consider the image on the right of Mathew Benjamin Brady flogged when a slave in the Southern States of America. This photograph was take at Baton Rouge during the American Civil War in 1863.

Slaves were powerless and treated differently in Roman law receiving more severe punishments than a free person for the same crime and being valued less in that a crime against a slave received a lesser punishment than the same crime committed against a free person. These dual standards had existed from the early days of the Republic when a thief would be flogged and handed over to their victims but if a slave committed theft they were flogged and then thrown to their death from the Tarpeian Rock.

Gratuitous cruelty is mentioned by several writers, Pliny the Elder, for example, said that Publius Vedius Pollio, who was a friend of the Emperor Augustus, used to throw slaves that he had sentenced to death into a pond of lampreys so he could enjoy the sight of them being torn to pieces.

Seneca, who was born a decade after Vedius’ death in 15 BC was close to the imperial family and would have heard the story first hand:

“When one of the slaves had broken a crystal cup, Vedius ordered him …… to be thrown to the huge lampreys which he kept in a fish pond ….. the lad slipped from his captors and fled to Caesar’s (Augustus’) feet, begging only that he might die in some other way – anything but being eaten. Caesar, shocked by such an innovation in cruelty, ordered that the boy be pardoned, ….. that all the crystal cups be broken before his eyes, and that the fish pond be filled up.” 2

Seneca uses this anecdote to make a point that gives us a insight to at least one Roman’s attitude to slavery:

“Even slaves have the right of refuge at the status of a god; and, although the law allows anything in dealing with a slave, yet, in dealing with a human being, there is an extreme which the right common to all living creatures refuses to allow.”

Tactitus tells a chilling tale of an event that occurred during the reign of Nero but one that reveals that not all Romans had a total disregard for the lives of slaves:

“The city prefect, Pedanius Secundus, was murdered by one of his own slaves; either because he had been refused emancipation after Pedanius had agreed to the price, or because he had contracted a passion for a catamite, and declined to tolerate the rivalry of his owner.

Be that as it may, when the whole of the domestics who had been resident under the same roof ought, in accordance with the old custom, to have been led to execution, the rapid assembly of the populace, bent on protecting so many innocent lives, brought matters to the point of sedition, and the senate house was besieged.”

The public had risen up to besiege the Senate because the old law called for all the slaves living under the ex-consul Pedanius’ roof to be put to death including the women and children.

Caius Cassius spoke for the majority of senators when he put forward the argument that it was impossible that none of the other 400 slaves living in Pedanius’ house knew of the murderer’s plan yet none of them had prevented what he called “the treason of one slave”. In his view the only way the slave owner was safe was by his slaves policing each other knowing the awful vengeance that would befall them if their master was murdered.

“…….. you will never coerce such a medley of humanity except by terror.”

His arguments won the day but the angry crowd outside the senate still prevented the punishments being carried out causing Nero to order soldiers to line the route that the condemned walked to their execution. 4

Another murder, this time described by Pliny the Younger, reveals the contradictory nature of the Roman view of slaves. Pliny tells his friend Acilius that he has heard of the murder of Largius Macedo, the son a freedman who had risen to the rank of praetor. 5 Pliny says:

“He was known to be an overbearing and cruel master, and one who forgot — or rather remembered to keenly — that his own father had been a slave.”

When bathing at his villa near Formiae he was set upon by his slaves and beaten. He was left for dead and his slaves fled; some had been recaptured and punished before Macedo died but, given his reputation for cruelty, the intriguing feature of this story is Pliny’s reaction to the event:

“Do you realise how many dangers, how many injuries, how many abuses we may be exposed to? And no one can feel safe, even if he is a lenient and kind master.

Slaves are ruined by their own evil natures, not by a master’s cruelty.” 6

The Romans were fearful of slave uprisings, Nero is reputed to have rejected the proposal that slaves should wear uniforms on the basis that the slaves would realise just how many of them there were. And as shown in Caius Cassius’ arguments above they were firm believers in management by terror. When Spartacus, the Thracian gladiator, rebelled and was defeated in 73 BC his 6,000 captured followers were crucified along one hundred miles of the Appian Way from Rome to Capua to make quite certain that everyone got the message.

In a society that included rape in its foundation myths as in the rape of Rhea Silva by the god Mars and the rape of the Sabine women by Roman men it is not wholly surprising that sexual violence towards women and especially slaves was common. Male and female slaves were sexually abused and raped by their owners and many would have been purchased specifically for that purpose.

Female slaves were expected to provide sexual services to their masters as a matter of course but they ran the risk of being punished if caught by a jealous wife despite having had no choice in the matter.

Mary Beard, as ever, puts it very succinctly:

“It was not simply that no one minded if a man slept with his slave. That was, in part at least, what slaves were for.” 9

Social Death

The phrase “social death” has been used to describe the slave’s status, they did not exist as people within Roman society; they were the butt of jokes, consistently characterised as stupid and regularly compared with “other” dumb animals. A person who becomes a slave, as opposed to being born into slavery, is stripped of every element of their previous identity including being renamed. They are now just an object.

Roman law and custom consistently reflected the fact that slaves were inferior to both freedmen and citizens. This was regardless of the role they played in society; there were many Greek doctors, teachers and architects who were slaves and despite having skills and often an intellect their owners lacked they remained inferior.

Keith Bradley perfectly sums up a slave’s status in Rome:

“The inferiority of the Roman slave was complete and unqualified.” 10

By law slaves could not marry or have families although many had informal, lasting relationships and it was usually in their masters interest for slaves to have children as they automatically became slaves. However, slave relationships were insecure as a master could sell either party or move them to another of his properties. There is evidence that some slaves were sold with the express condition that they were to be taken elsewhere. 11

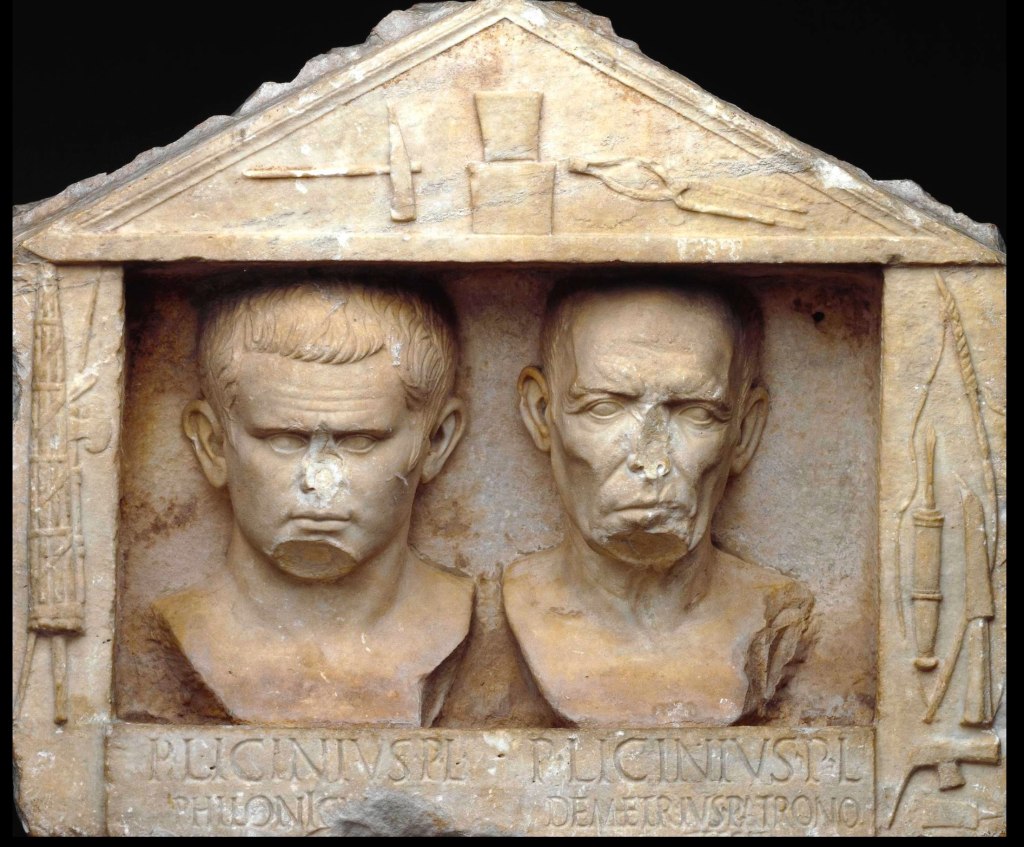

One of the fundamental aspect of Roman society was for an individual to present themselves in the context of their ancestors; elite Romans kept death masks of their forebears in niches inside the family home as proof of their status 12 because ancestry was important to Romans, it was referenced in their name and confirmed their position in society.

A slave had this basic privilege taken from them; when they were sold the trader had to declare their origin but not who their parents were or their family name. The slave was thereby separated from their ancestry, they had no family, no tribe, no heritage and were formally a non-person. Bradley gives an example of a slave sale document:

“The man who sold the girl was Artemidorus, sone of Aristotle’s, the man who bought her Pamphilos, otherwise known as Canopus, son of Aegyptos.”

But she was merely:

‘the slave girl Abaskantis, or by whatever other name she may be known, a ten-year-old Galatian.’” 13

The household slave whose ancestry and identity had already been taken from them was usually given a new name by their owner. When hearing that a slave had no right to own property recognise that this extended to having no right to their name. Robert Knapp believes this was:

“……. the most symbolically laden act of identity management. The act of naming re-identifies the slave as the property of the new owner; it embodies the attempt to eliminate that person’s former self and to show that identity is under the control of the new master.” 14

In the early days of Rome slaves were mostly referred to as puer, boy or lad, in the same way that “boy’ was used as an insulting and demeaning name by white colonists for a black African man of any age. Over time puer became por and, to differentiate between slaves and until the late days of the Republic, por was attached to the owner’s name so a slave called Marcipor simply meant Marcus’ slave.

Eventually the number of slaves owned by an individual made this system unworkable and owners began to choose names for their slaves; these often referred to the slave’s ethnicity and quite often suggest a level of black humour or a way of reminding the slave of their duties or expected demeanour: such as Felix, happy; Eros, the Greek god of love; Hermes, the swift messenger of the gods; Onesimus, helpful; Melissa, honeybee or busy; Vitalio, lively.

In the late Republic the naming system became more sophisticated and the slave’s given name was added to his or her master’s name appended with servus which had replaced por. So, Tiro, a slave owned by Marcus Tullius Cicero, would have had a full name of Tiro Marcus Tullius servus and when he was manumitted become Marcus Tullius Tiro. 15

Being Sold

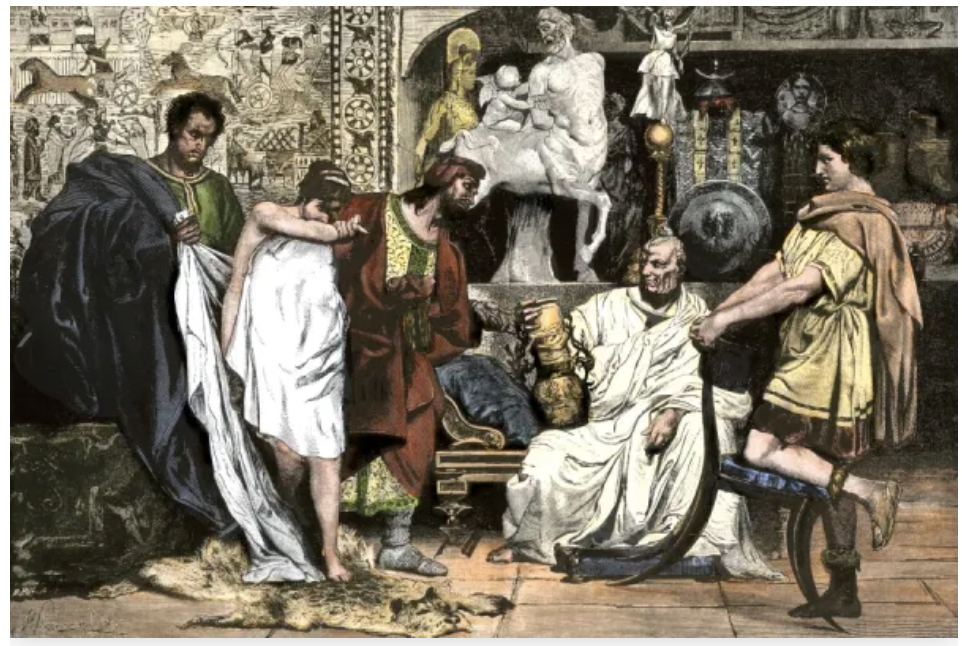

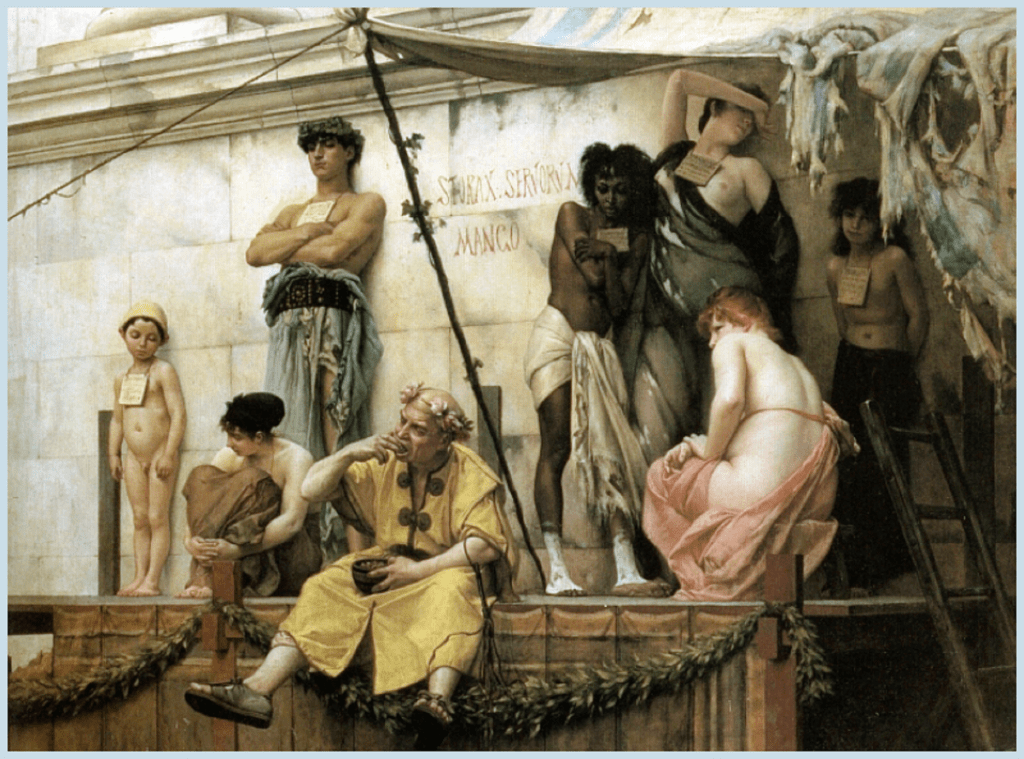

When a person was put up for sale the trader had to declare whether they suffered from any disease or defect that might effect their usefulness, and whether they were prone to running away or loitering when running errands. Two other declarations provide an insight to the slave’s lot in life; the dealer had to declare whether they had attempted suicide or had been sent to arena to fight wild animals.

All of this information was written on a sign hung around the slaves neck as they stood on a raised platform (catasta) in the market place. If they were freshly imported their feet were whitened with chalk.

Some of the mandated declarations directly effected the salves value. For example a slave labelled servi soluti, free slave, was worth more than one labelled servi vincti, chained or fettered slave. Some slaves were sold in chains because according to Pomponius, a jurist who lived in the time of Hadrian, if a slave had been chained in the past it was better to sell them in chains as this avoided the seller declaring that history. 17

The buyer could ask for the slave to be undressed and he was free to prod and poke as much as he wished. For someone born into slavery the humiliation of the catasta would have been something they, to some degree, were used to, they were bred to know that they had no rights of ownership of their own bodies but we cannot imagine the feeling of despair, shame, powerlessness and violation felt by enslaved victims of war, piracy or the frontier slave trade standing naked with their chalk whitened feet on a wooden box in the middle of a busy market.

Varro, in his treatise on agriculture, gave advice on buying slaves for the farm which we will return to when considering the work undertaken by slaves but he also explains there are six ways in which slaves can be acquired:

- Inheritance;

- Mancipatio, mancipation, from one who has the legal right to transfer: a formal act of purchase in the presence of five Roman citizens, the purchaser laid their hands on the object being purchased, asserted their ownership, struck the scales held by one of the witnesses with a copper or bronze ingot and then gave the price to the seller; 18

- From someone who has a right to cede;

- Usucapio: right of possession, which in the case of moveable property was one year as long as the slave had been acquired in good faith and not stolen;

- Purchase of war booty at auction;

- Sectio: purchase of confiscated property.

His advice to the buyer was:

“In the purchase of slaves, it is customary for the peculium 19 to go with the slave, unless it is expressly excepted; and for a guarantee to be given that he is sound and has not committed thefts or damage; or, if the transfer is not by mancipation, double the amount is guaranteed, or merely the purchase price, if this be agreed on.” 20

The Romans detached themselves from anything other than the job they needed the slave to undertake.

A concubine needed to be pretty, a herdsman strong enough to protect the herd and live in mountains all summer, a tutor had to be proficient in Greek and classic literature, etc.

Right: a statue of a slave who appears to be African. Race was rarely an issue to Roman buyers who were focussed on practical functionality. 21

The slave was a tool, a machine, a piece of equipment that was selected mostly on their ability to perform a specific role.

Living Conditions

It is impossible to generalise regarding the living conditions of slaves as they lived and worked in a wide variety of environments from villas to town houses, farms to factories and mines to dockyards. The limited evidence available suggests that the innate practicality of Romans meant that owners provided the minimum required to keep the slave able to perform their function.

In her study of the excavations at Pompeii Mary Beard wonders if household slaves mostly slept where they worked, outside their master or mistress’ door, on the floor of the kitchen or on an upper floor in rooms that also acted as storage areas. 22 And, it does seem likely that the absence of obvious slave quarters in most archeological sites points to household slaves finding a place under the stairs, in a store room or in a corridor to roll out a sleeping mat.

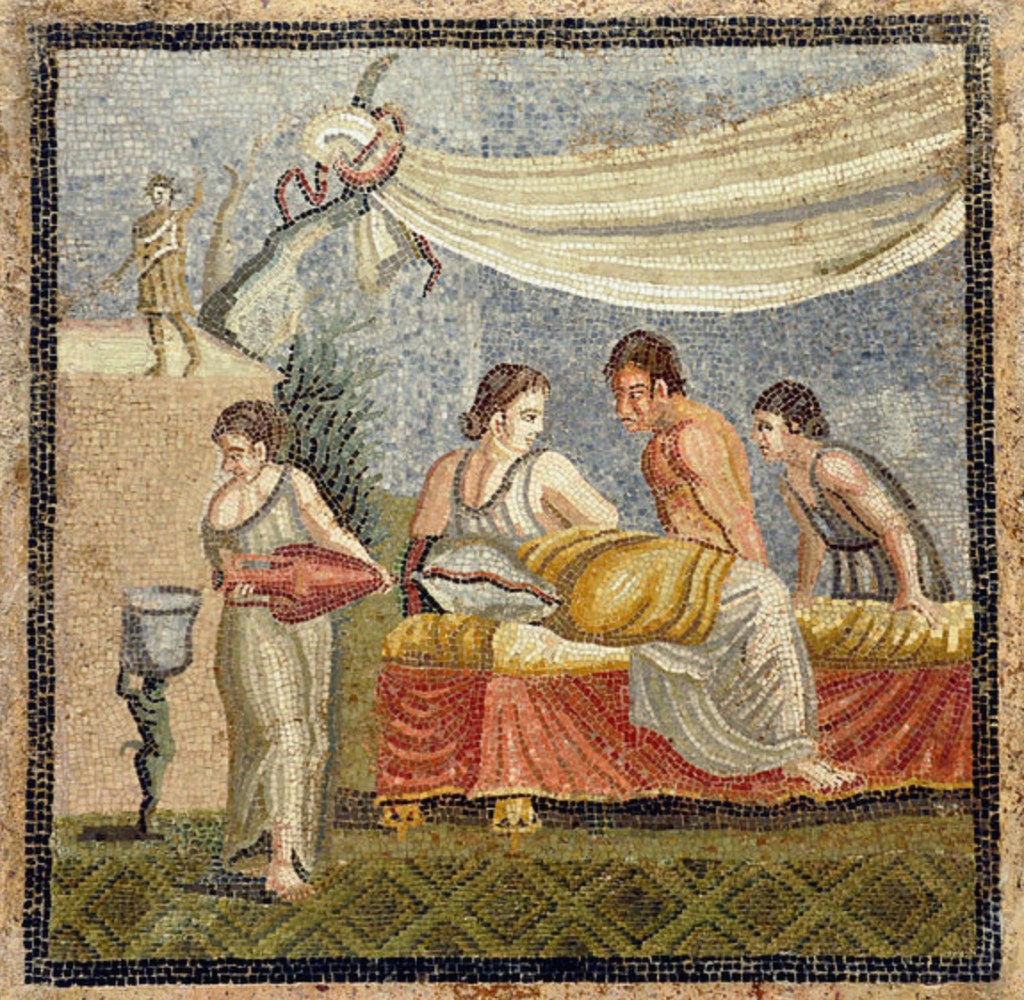

One of the murals in the house of Caecilius Jucundus at Pompeii potentially provides some insights; it is a mildly erotic scene showing a naked couple in bed but the interesting component is a pale female figure behind and to the left of the naked woman. It seems likely that this depicts a slave, a bedroom attendant or ladies maid. She stands close to the lovers and although she is averting her eyes she has witnessed or will witness their love making.

The second image of love making is displayed on a mosaic found in Centocelle near Rome. The scene appears to be outdoors and the couple recline on a bed wrapped in colourful cloths under a white shade. In the distance we can see a statue of the god Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and fertility, and in the foreground a slave girl pours wine into a bowl held by a satyr, best known for their wild and lecherous behaviour. The couple are flanked by a second slave girl. The symbolism is not difficult to interpret yet, once again there are two demurely dressed slaves who will be witness to their love making.

These are two examples of the ubiquitous nature of slaves, they are with their master or mistress at their most intimate moments and to the Roman viewer were probably no more surprising to be included in a love scene than the bed or the amphora of wine.

It is pure speculation but not unreasonable to assume that these ladies’ maids probably never left their mistress’ side, accompanying her twenty four hours a day and sleeping on the floor at the foot of her bed in the same way that a maid would sleep at the foot of Queen Elizabeth I bed.

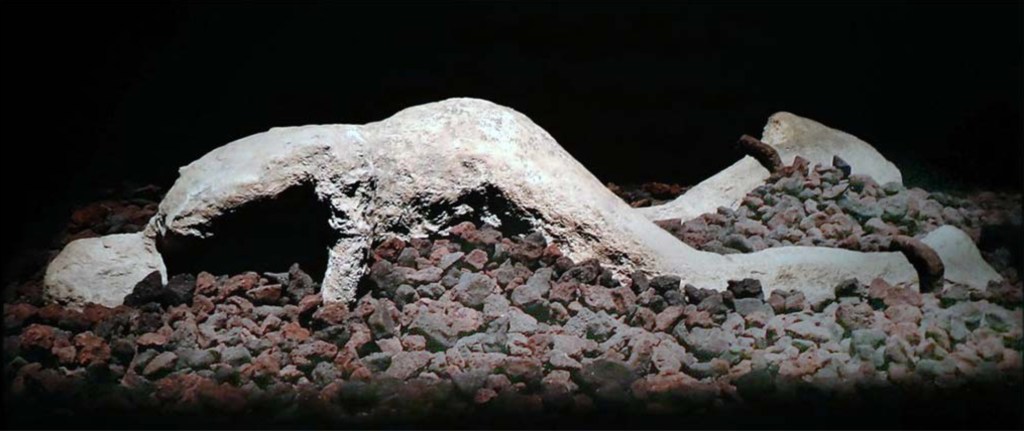

The two rooms shown above have been excavated at Civita Giuliana, a villa outside Pompeii, and are assumed to have been slave quarters. In both cases the rooms are small with rough un-plastered walls and although both are furnished with simple beds they appear to double as store rooms. Excavations at Civita Giuliana have perviously revealed a saddled horse and a ceremonial chariot so it is argued that the room with the horse harnesses was used by the grooms and potentially a charioteer.

The second room is a little different in that one of the beds is of a more expensive design and has a mattress which suggests some hierarchy amongst the slaves within this household. However, the discovery of two mice and a rat in the same room shows that the slaves’ living conditions were far from luxurious.

There is some evidence of the conditions that deep-vein miners, including children, had to survive. Diodorus of Sicily, who wrote his histories between 60 and 40 BC, described the working and living conditions of slave miners in the gold mines of Egypt:

“…… they are a great multitude and are all bound in chains — work at their task unceasingly both by day and throughout the entire night, enjoying no respite and being carefully cut off from any means of escape; since guards of foreign soldiers who speak a language different from theirs stand watch over them, so that not a man, either by conversation or by some contact of a friendly nature, is able to corrupt one of his keepers.

And since no opportunity is afforded any of them to care for his body and they have no garment to cover their shame, no man can look upon unfortunate wretches without feeling pity for them because of the exceeding hardships they suffer. For no leniency or respite of any kind is given to any man who is sick, or maimed, or aged, or in the case of a woman for her weakness, 28 but all without exception are compelled by blows to persevere in their labours, until through ill-treatment they die in the midst of their tortures.” 27

Farm slaves mostly worked in the open air which must have given them some chance of a longer lifespan than mining but there is evidence that the conditions under which they worked and lived could be miserable. Columella describes the farm slave quarters as being cubicles that appear to be part of the kitchen but he also advises how to design the slave prison or ergastulum or carcer rusticus:

…… there will be placed a spacious and high kitchen, that the rafters may be free from the danger of fire, and that it may offer a convenient stopping-place for the slave household at every season of the year.

It will be best that cubicles for unfettered slaves be built to admit the midday sun at the equinox;

……. for those who are in chains there should be an underground prison, as wholesome as possible, receiving light through a number of narrow windows built so high from the ground that they cannot be reached with the hand.” 28

The ergastulum was probably originally designed to confine barbarian 29 war slaves who were often newly enslaved, captured warriors and too dangerous to have unconstrained around the farm. But the prison was also used to punish unruly slaves. Pliny the Elder mentions slaves imprisoned in the ergastulum as working the land in chain gangs during the day. 30

It is not clear how common chained gangs of farm workers could have been given the nature of farm work. It is possible to imagine a chain gang digging ditches or hoeing a field but much harder to think that this would be practical when the slaves were pruning olive trees or vines or, for that matter picking olives or grapes. It is possible that the leg irons found on some skeletons and, at least one, body at Pompeii were attached to a chain at night but unattached during the day and it is equally possible that chaining slaves was a time limited punishment rather than a permanent way of managing them.

Agricultural workers were not then only slaves to be chained, Suetonius writes of Lucius Voltacilius Pilutus, who became a freedman teacher but had been a doorman chained to the door post to stop him running away. Apparently this was quite normal. 32

Being Freed

Roman society was full of contradictions and it is intriguing that a non person, a slave, could be freed, given their erstwhile owner’s family name and become a productive member of society. Not only could a freedman become successful in administration or commerce their sons could vote and hold public office. One, Pertinax, even became emperor albeit for just three months in AD 193. This is not the place to be sidetracked by a discussion on the comparative merits of slave systems but to argue that this meant the Roman system of slavery was somehow benevolent because they freed slaves is lazy and misleading.

Judge Robert M. Toms presided over ten of the Nuremberg Trials that tried Nazi war criminals after World War II during which he established the principle that good treatment of slaves could not be used as a mitigating argument:

“Slavery may exist even without torture. Slaves may be well fed and well clothed and comfortably housed, but they are still slaves if without lawful process they are deprived of their freedom by forceful restraint.

We might eliminate all proof of ill treatment, overlook the starvation and beatings and other barbarous acts, but the admitted fact of slavery – compulsory uncompensated labour – would still remain.

There is no such thing as benevolent slavery. Involuntary servitude, even if tempered by humane treatment, is still slavery.” 34

Dionysius in Roman Antiquities, his history of Rome, describes how Sevius Tullius, the 6th king of Rome 578 – 535 BC introduced the concept of freeing slaves into Roman law. Tullius argued that owners could be trusted to only free good men, that slaves would work harder hoping that they would prove themselves worthy of freedom and that the freemen and their sons would ensure that :

“The state would never lack for armed forces of its own, but would always have sufficient troops, even if it should be forced to make war against all

the world.” 36

If these advantages to the public didn’t persuade his patrician audience he casually mentioned that, of course, the elite Romans would benefit from having freedmen and the children of freedmen as their clients to vote for them and to help increase their wealth.

From the 6th century BC until around AD 1000 Romans continued to free slaves, manumission was an important component of a complex society and the social structures that made the Roman world function. However, freedom was only a realistic possibility for a tiny percentage of slaves and many groups had very limited or non-existent chances of freedom including most agricultural slaves who made up as many as a third of all Roman slaves, miners who carried out hard labour in dreadful conditions and probably most industrial trades including bakery, pottery and brick making.

The majority of slaves had little or no hope of manumission.

Manumission was was taxed by the state to the tune of 5% of the slave’s value and was carefully regulated, in the 2nd century AD the law stood as:

Someone who had more than two but not more that ten slaves was permitted to free up to half their number;

Someone who had more than ten but not more than thirty slaves was permitted to free up to one third.

Someone who had more than thirty but not more than one hundred was allowed to free up to a quarter.

Someone who had more than one hundred but not more than five hundred was permitted to free not more than one-fifth.

Someone owning more than five hundred ……. may [not] lawfully free more than one hundred slaves. 38

Beard 39 estimates that Cicero had “an absolute minimum” of two hundred slaves; under the law he could free 40 which would be commendable if it didn’t mean that thye other 160 remained enslaved. Pliny the younger owned at least 500 slaves so could only have freed 100 leaving 400 as slaves. Caecilius Isidorus, the wealthy freedman who left 4,116 slave in his will could only have freed 100 leaving over 4,000 enslaved.

With arguments that have a striking similarity to the arguments against immigration on the 21st century Dionyssus lamented that by his day, in the early years of the Imperial Age, slaves were engaged in theft, housebreaking, prostitution and all sorts of other crime allowing them to save up the money to buy their freedom. Others were in cahoots with their masters in nefarious activities and were freed as a reward or were freed on a whim to gain popularity or just to increase the number of freemen in their patron’s funeral procession.

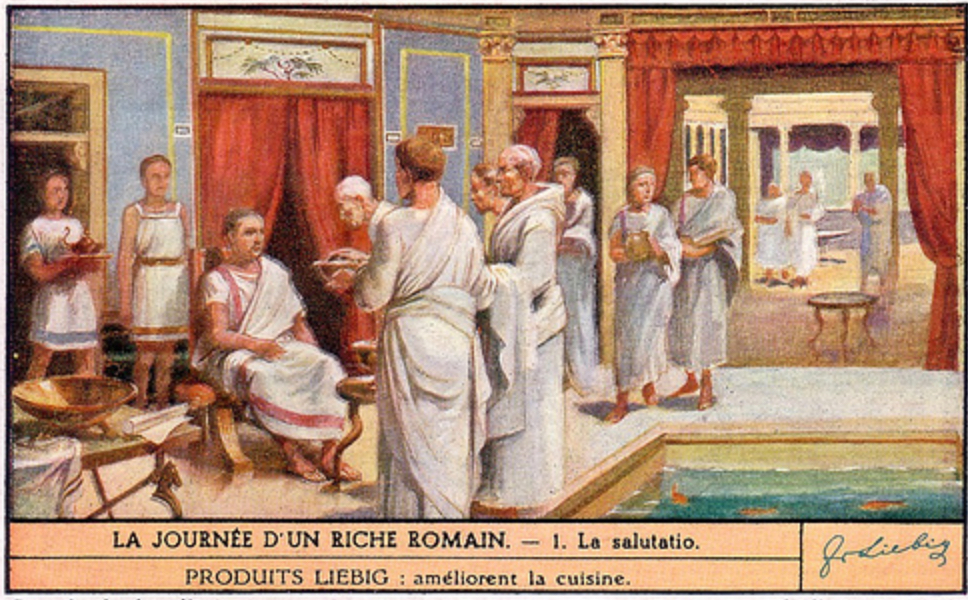

The other factor to bear in mind is that freeing a slave did not release them into the Roman world to make their way totally independent from their erstwhile master. Typically the freeman became a client of his original owner, now his patron, and expected to call on him twice a day; if a freeman died intestate his property reverted to his patron. A client was typically running a business for, or in partnership, with his patron so at their first meeting of the day, the morning salutatio he would give his patron a business update and quite possibly hand over his share of the takings.

For an elite Roman, for whom trade was seen as beneath his status, the patron client relationship allowed him to finance his lifestyle whilst keeping his source of funds at arms length. One assumes this is how Vespasian engaged in the unpleasant trade in castrated slaves.

The patron client relationship had many facets, wealthy Romans flaunted their wealth in many ways and visiting the forum or the senate followed by a gaggle of clients was one of those. A client would canvas for his patron at election time and as some accrued great wealth running their businesses they were called on and able to finance their patron’s political career.

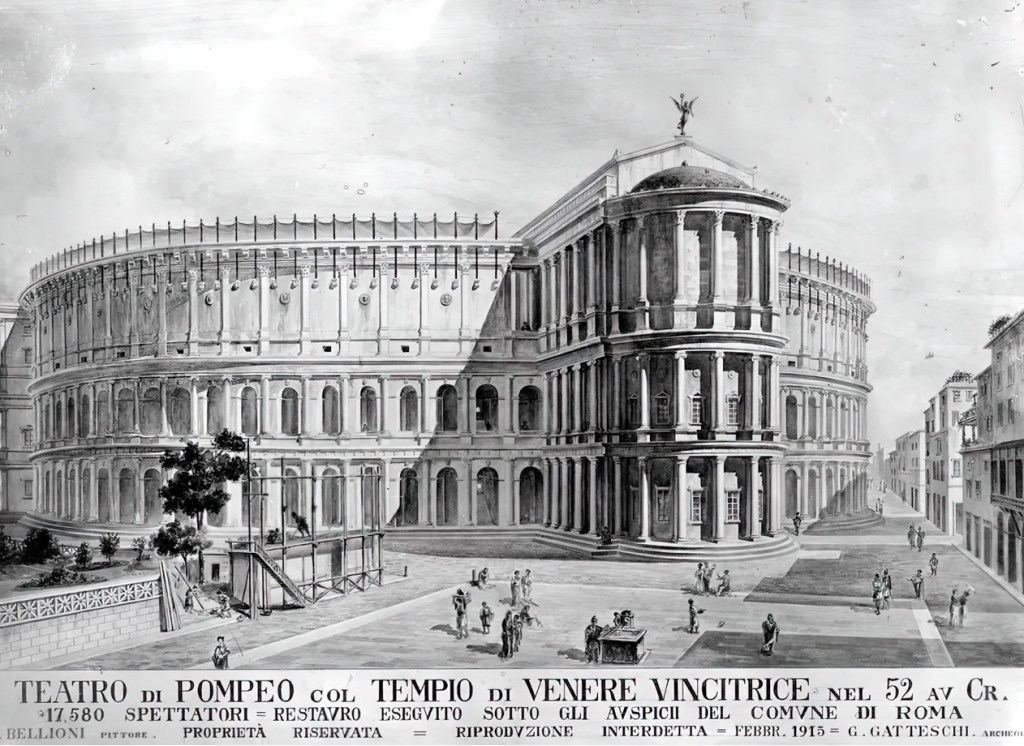

Remarkable examples include a freedman by the name of Demetrius who is reported to have financed the construction of Pompey’s theatre in Rome and who, when he died left a fortune of 24 million denarii which could total equate to over 1.5 billion British pounds. 41

Whilst these and many other examples present a positive picture of being a freedman or freedwomen, and no doubt it was better than being a slave, the legal obligations of a client to their patron lasted a lifetime. He, or she was obliged to provide services to their patron for free and this was often extended to include the patron’s friends or people he washed to influence.

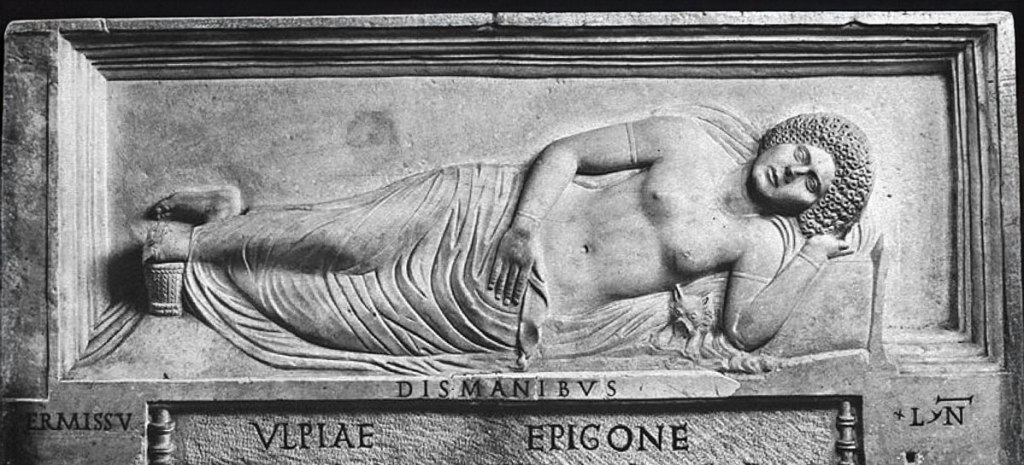

Retirement

Cato advised farm owners to sell off any damaged or broken equipment including old or sickly slaves so it is not surprising that when a slave grew too old or infirm to justify the cost of his or her upkeep many owners simply abandoned them at the sanctuary of Aesculapius, the god of medicine, healing, rejuvenation and physicians on Tiber island.

Left: Statue of Aesculapius 42

Suetonius 43wrote that, in AD 47 the Emperor Claudius decreed:

“When certain men were exposing their sick and worn out slaves on the Island of Aesculapius because of the trouble of treating them, Claudius decreed that all such slaves were free, and that if they recovered, they should not return to the control of their master; but if anyone preferred to kill such a slave rather than to abandon him, he was liable to the charge of murder. .”

Markets and Traders

The scale of slavery in the Roman world meant that slaves were always on sale in any large town or city yet only a few major markets are mentioned by the classic writers. This is possibly because the sale of slaves was so common it was unnecessary to even mention. Some historians compare slave ownership at the end of the Republic with car ownership in the modern western world; car dealerships are too common and mundane to be worthy of mention when describing a British city.

Whilst not all slaves would have been sold in the city of Rome it is quite probable that the majority were; Rome had the highest concentration of slave ownership and the wealthy landowners were based in the city for much of the year.

Taking this into account whilst accepting, as previously mentioned, that the number of captives taken in war was often exaggerated, on occasion there must have been incredible gluts in the market, although many would have been sold to the slave traders that followed the legions and sold nearer to their place of capture.

- 11,000 Italic people were alleged to have been enslaved in 290 BC

- 65,000 Sardinians were up for sale in 177 BC;

- 150,000 Greeks from the destruction of the cities of Epirus in 167 BC;

- 55,000 Carthaginians in 146 BC;

- 125,000 Gauls a year on average between 58 to 50 BC;

- 44,000 Salassi in 25 BC

- 97,000 Jews between AD 66 and 67

- 100,000 Jews between AD 132 and 35. 44

Rome

Given the scale of slave ownership by the average Roman citizen there must have been some form of permanent or occasional market 46 in every Roman city or town. In Rome there are two known sites; beside the Temple of Castor in the Forum for everyday purchases and the Saepta Julia 47 in the Campus Martius just outside the city if the buyer was looking for someone more exotic. Neither were purpose built slave markets.

Seneca says that there was a particular noise to be heard from near the Temple of Castor, the noise of “the regular, daily traffic in slaves”; we can imagine slave dealers calling out their wares like a Cockney barrow boys.

Ephesus

Philostratus 48 refers to Ephesus on the west coast of modern Turkey in the 1st century AD:

“…….one can buy here on the spot slaves from Pontus or Lydia or Phrygia, for indeed you can meet whole droves of them being conducted hither, since these like other barbarous races have always been subject to foreign masters, and as yet see nothing disgraceful in servitude; anyhow with the Phrygians it is a fashion even to sell their children.”

Pontus, Lydia and Phrygia were all parts of Roman provinces having been absorbed into the Republic between 133 and 62 BC. Pontos on the southern shore of the Black Sea fits the mould of a frontier area but Lydia and Phrygia were both in central Anatolia.

Varro (116 to 27 BC) describes Ephesus as a centre of the slave trade and it would be logical to assume that this wealthy city on the shores of the eastern Mediterranean was a intermediate market where slaves from across Asia Minor and the Black Sea were purchased by traders planning to sell them in the cities of Greece and Italy.

Gaius Sallustius Passienus Crispus was the proconsul, i.e. governor of Asia 49 between 42 and 43 AD and it is possible that he became the patron of the slave traders based at Ephesus. He was a man of immense wealth, one of the Roman elite and we can only wonder how much of his wealth came from financing the slave trade.

Delos

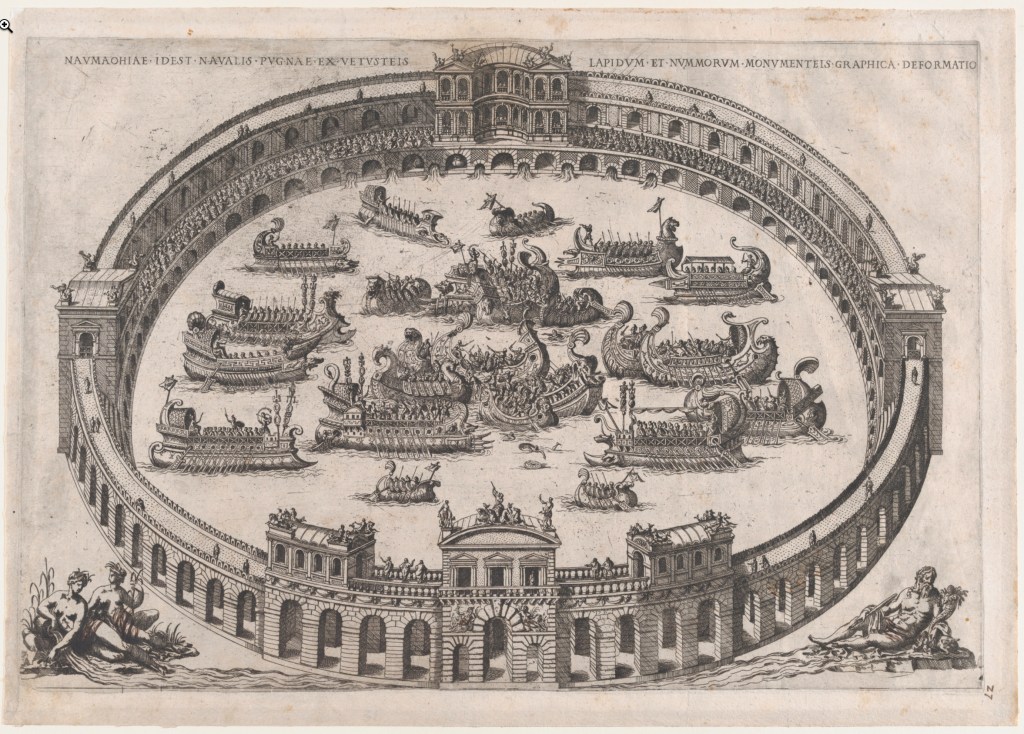

Delos is a small island in the Cyclades group of island in the Aegean Sea. I can testify that the short passage there from nearby Paros is a horrible crossing in a small boat fighting both wind and current. People always appear to have lived there and as the alleged birthplace of Apollo and Artemis it became an important as a place of worship as early as 700 BC and developed to be the religious centre of the Aegean.

Naxos, Paros and then Athens controlled the island at different times and when Athens created the navy league in 478 BC it became the headquarters of the federation with the temple of Apollo as its treasury.

The Seleucid king Antiochus III had inherited much of Alexander the Great’s conquests in Asia and had begun to call himself the king of kings. The Seleucid Empire and Carthage both had powerful fleets that dominated the Mediterranean but in 190 BC Lucius Scipio, with significant help from Macedonian and Greek allies, defeated Antiochus at the Battle of Magnesia forcing him to leave Anatolia and give up his Mediterranean fleet. Forty-four years later the end of the Punic Wars in 146 BC and the destruction of the Carthaginian fleet firmly established Rome as the dominant power in the Mediterranean despite its lack of a powerful navy.

Rome’s insatiable demand for slaves and other goods from the east realigned the trading patterns in the region. Rhodes had been an important port for centuries but in 166 BC Rome took Delos from the control of Rhodes and passed it to its ally Athens whilst making Delos a free port. Excluding Delos from the normal two percent harbour dues put Rhode’s economy into long term decline and the Athenians were hit with the cost of administering Delos without any income.

Historically Egypt had marketed its grain harvest through Rhodes but reduced harbour fees and an increasing number of Italian merchants settling on the Delos caused Egypt to switch and the island quickly became the most important trading hub in the Aegean.

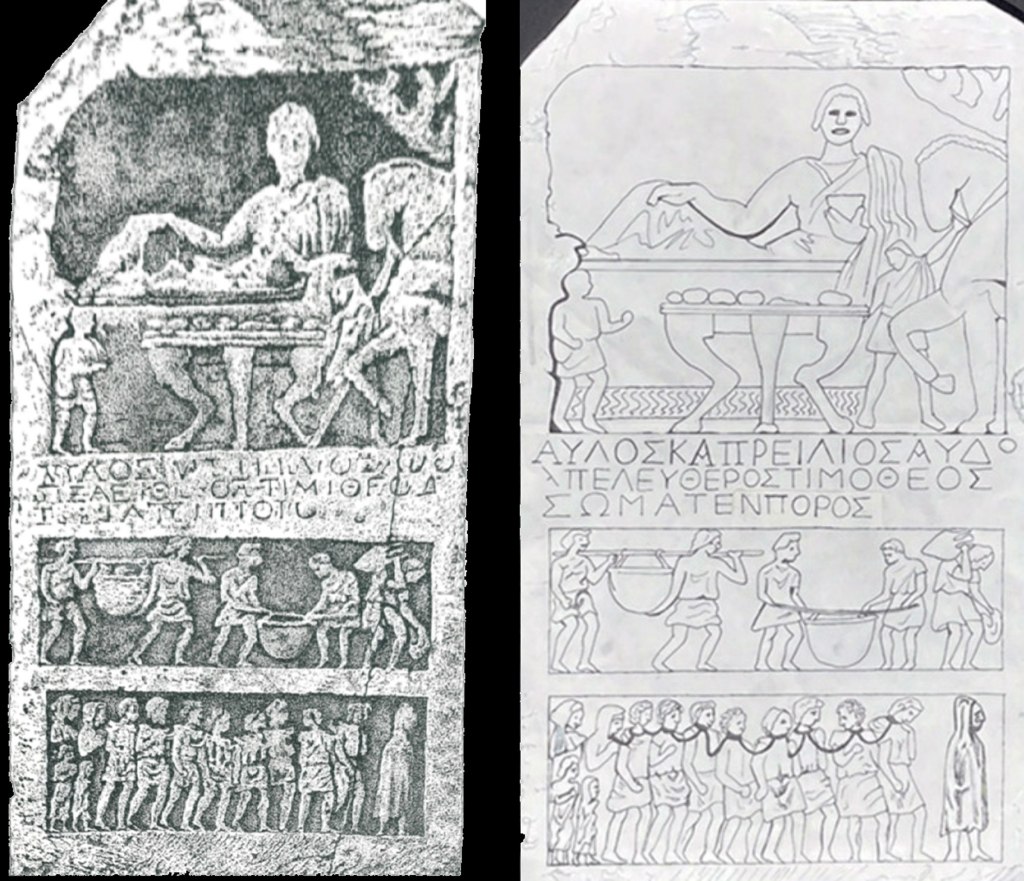

Its importance grew not just as general trading centre but as one of the largest slave markets of the ancient world. Many of the slaves sold at Delos were purchased from pirates operating in the eastern Mediterranean; but we cannot know how this compared in terms of scale with the slaves being captured and transported by traders from Anatolia, the Black Sea and all points east.

Strabo, the Greek geographer, wrote that it was the main hub of the slaves trade bringing slaves from the east to Rome with up to a 10,000 slaves sold in a single day. This number is much discussed and many historians suggest it is widely exaggerated 51 but perhaps Strabo was referring to the total sales at the annual festival on the island which had originally been religious but evolved into a trade fair.

Delos was attacked in 88 BC by King Mithridates of Pontus and again by the pirate Athenodorus in 69 BC. It subsequently fell into decline but Roman trade routes had already begun to move away from the island by that time.

Side

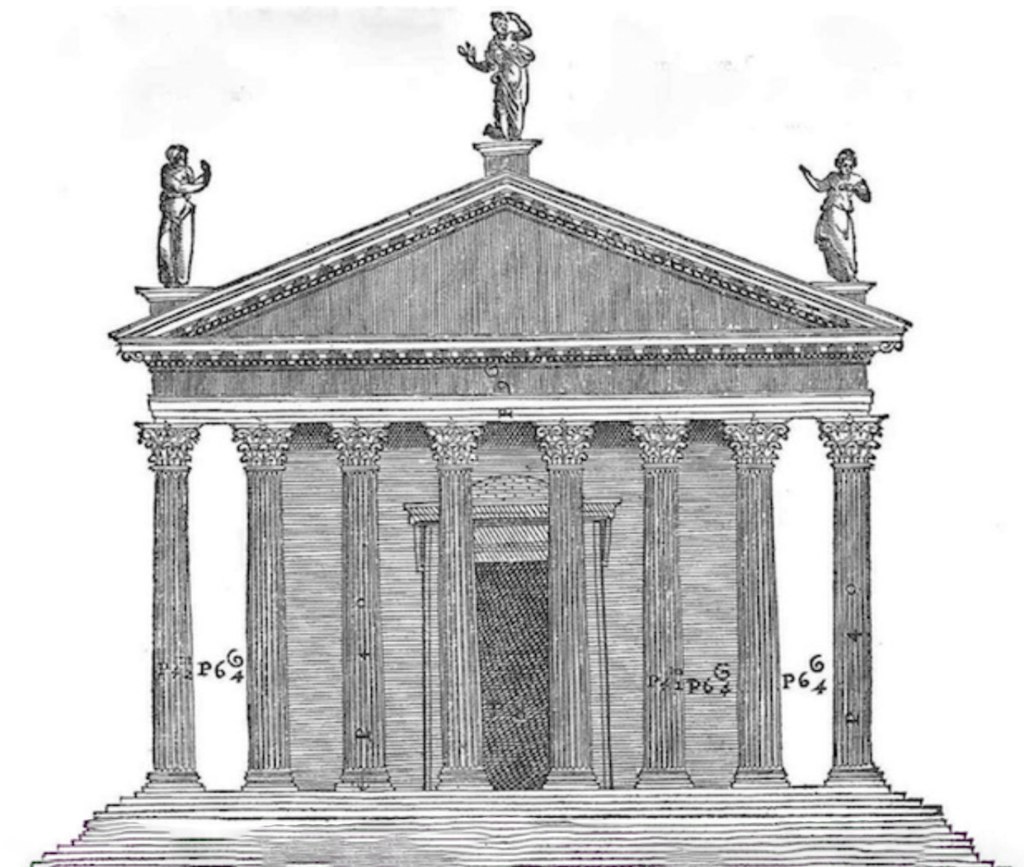

The city Side on the coast to the east of modern Antalya in southern Turkey was an ancient city that had been Hellenised by Alexander the Great.

It was a major slave port from the early 2nd century BC until suppressed but not closed by Pompey in 67 BC.

It rose again as the main base for Cilician pirates in the time of Emperor Augustus.

After the demise of Delos it was not in Rome’s interests to completely close another slave port so in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD Side became fabulously wealthy on the back of the slave trade building many monumental buildings including the Temple of Apollo (see above), a 15,000 seater theatre, baths, a library and forum.

It continued to be an important slave market until the 4th century when it went into decline.

The Indian Ocean

Africa had been recognised as a source of slaves from at least the time that Caligula was Emperor of Rome between 37 to 41 AD.

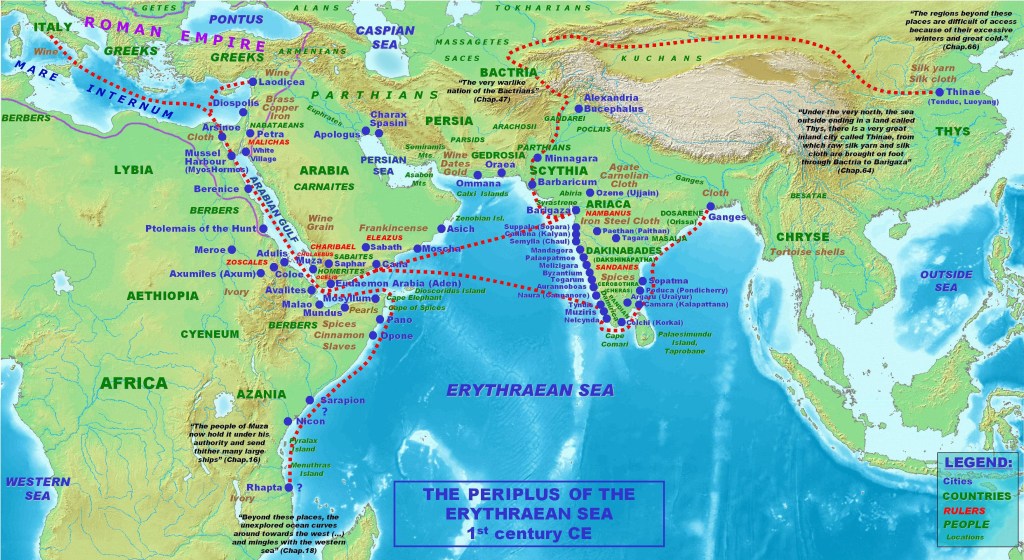

African slaves are mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a sailing guide for the merchants of the Roman Empire describing ports and trading opportunities through the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Indian sub-continent and as far east as modern day Bangladesh and Myanmar and, in the other direction, round the Horn of Africa and south along the east coast of Africa to Rhapta, a lost trading centre that was probably in the Rufiji delta in modern day Tanzania.

For each port along the vast coastline covered by the Periplus the merchants are given notes on navigation, a brief political overview and a list of commodities that can be traded.

The Periplus describes that a merchant sailing from the Red Seas and then round the horn of Africa could “buy and sell” slaves along the route. At Malaô he could obtain slaves “on rare occasions”, or find “better-quality slaves” at Opônê but he is warned they are mostly sent to Egypt. If he has been successful in obtaining slaves he could sail to the island of Dioscuridês where there was a demand for female slaves from the Greek, Arab and Indian merchants who were based there. Today this route would take him from Berbera to Xaafuun in Somalia and then to the Island of Socotra which lies about 230 kilometres to the east-northeast of the Horn of Africa.

Specialist Markets and Traders

Slaves were a commodity that filled many positions in the economy of Rome but, like any commodity, there were some buyers with special requirements who needed to go to a specialist supplier.

In the period immediately following Ceasar’s assassination a man, possibly a freedman, by the name of Toranius Flaccus became a famous mango, a slave trader, specialising in high quality slaves. Toranius could count both Gaius Octavius (later the Emperor Augustus) with whom he is known to have dined and Marcus Antonius, Mark Antony, who had a taste for both beautiful female slaves and handsome boys, as customers.

There are occasional references to the trade in handsome young boys, including mention of a trader at Hierapolis, in Phrygia, who was a specialist supplier. 53 Pliny wrote that the root of the hyacinth was used as an ointment by slave traders to prevent puberty and preserve the looks of enslaved boys, this horrible idea was arguably preferable to castration which was the other method used. 54

Eunuchs were niche and valuable market in Rome. The Persian Kings had large numbers of enslaved eunuchs to guard their harems but despite frowning on the habits of decadent easterners eunuchs were also known in Rome in Augustus’ reign (27 BC to 14 AD) when there were eunuchs in the service of a number of elite Romans.

Nero is alleged to have had his teenage male lover, Sporus, castrated and this may have triggered a fashion for owning eunuchs during his reign (54 to 68 AD), a period that coincided with suggestions that the Emperor-to-be, Vespasian, was rebuilding his finances by bank rolling the specialist trade in eunuch slaves. This allegation has the ring of truth as eunuchs was so expensive they could only be afforded by the very wealthiest Romans, the equivalent to wearing a Patek Philippe watch. Pliny noted that the most expensive slave of all time was a eunuch and there was concern among traditionalists that this fashion was decadent and undermining the masculinity of the Romans who owned one.

Domitian (81 to 96 AD), who was Vespasian’s youngest son, made castration illegal but this was not a decision based on his humanity but more likely because of a zealous dislike of his brother and predecessor Titus. Domitian himself was reputed to have owned large numbers of eunuchs and catamites 56 including Earinus, a young castrate cup bearer who was famous for his beauty.

The practice continued and Hadrian (117 to 138 AD) issued an edict to make castration a capital offence. This is another one of the many contradictions that arise when looking at the elite Romans because Prudentius, a Roman poet, wrote that Hadrian’s boyfriend Antinous was a eunuch. Much later when the Eastern Roman Empire was centred on Constantinople the main source of eunuchs for the imperial court was from Abasgia on the northeastern shores of the Black Seas.

The Roman elite created and followed fashion as mindlessly as the super-rich in any society and this created some horrific niche markets that slave traders pandered to. According the Longinus who wrote a treatise on the sublime in the 1st century AD there was, at one time, a fashion for dwarf slaves and traders kept children in small cages in the hope of stunting their growth. There were also fashions for slaves with physical differences that fuelled a market in slaves missing limbs.

Conclusion

When researching slavery, especially the East African slave trade of the 17th and 18th centuries the challenge is the lack of sources. The challenge with looking at the Romans is being overwhelmed by the available material. If you are interested in the Romans in general but don’t know where to start I’d recommend Mary Beard and Guy de la Bédoyére, both are brilliant scholars who write for us ordinary folk, their books are not just sources of information but full of wit and insightful comment.

This essay, part 6 of my history of slavery, has focussed on ownership and the selling of slaves in the Roman world. Part 5 mostly focussed on the sources of slaves in the Roman world. and Part 7 will look at Slaves and Work.

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.