- Introduction

- The Gildas Myth

- Events Elsewhere

- The British Garrison in the 5th Century

- Was Britain Isolated after 410?

- Did Agriculture and Industry Decline?

- Romano-British or Just British?

- England Becomes Englisc

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

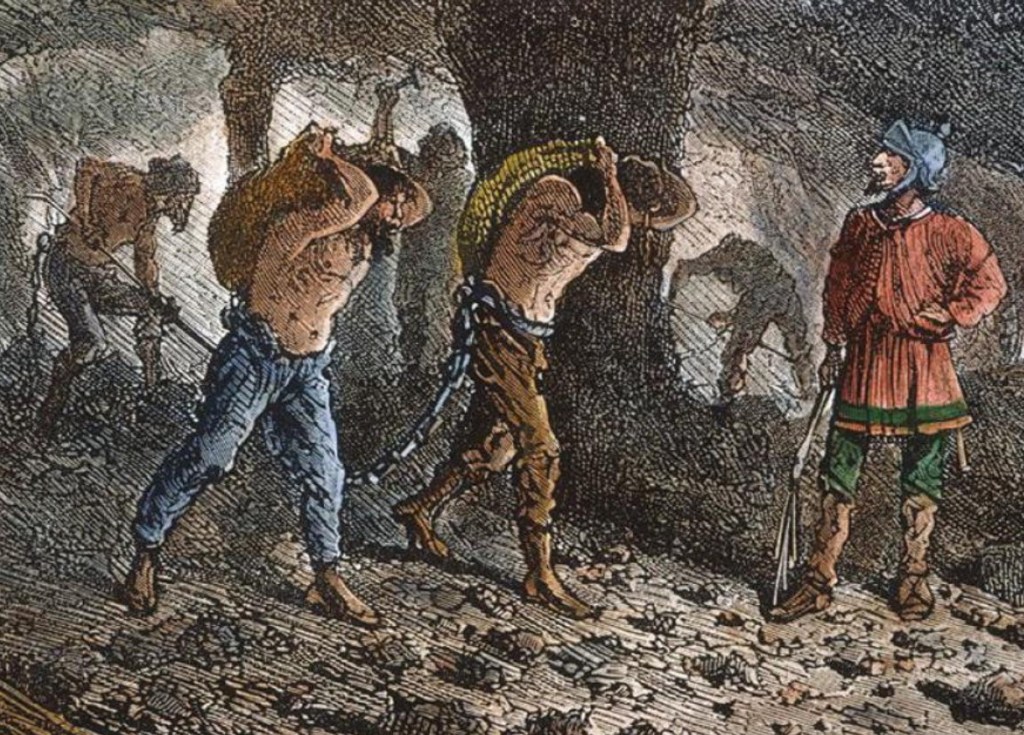

Previously I have looked at slavery in the ancient civilisations from Old Babylonia through the Minoans and Greeks to the Romans. Along the way I have touched on slavery in pre-Roman Europe. This article focusses on Britain and acts as a bridge between discussing slavery in the Roman and Post Roman world.

In Britain this is a transitional period that starts sometime in the 5th century AD and continues into the 7th century and that has been inaccurately and misleadingly labeled the Dark Ages.

The Gildas Myth

Late in the 5th or early 6th century AD, around 25 years after Romulus Augustus the last Roman Emperor of the West was desposed, Zosimus a Byzantine historian living in Constantinople mentions, pretty much in passing, that, in AD 410 Honorius, the Emperor of the Western Roman Empire:

“sent letters to the cities in Britain urging them to defend themselves“. 1

Romulus Augustus, considered to be the last Emperor of the Western Empire, ruled for around 10 months before being deposed in September AD 476.

His father, who placed the 14 year old Augustus on the throne in 475 was the “Master of Soldiers” (commander of the western Army) under the Emperor Julius Nepos.

Historians like to know when things happen so, based on Zosimus, AD 410 became established as the specific date for the end of Roman Britain.

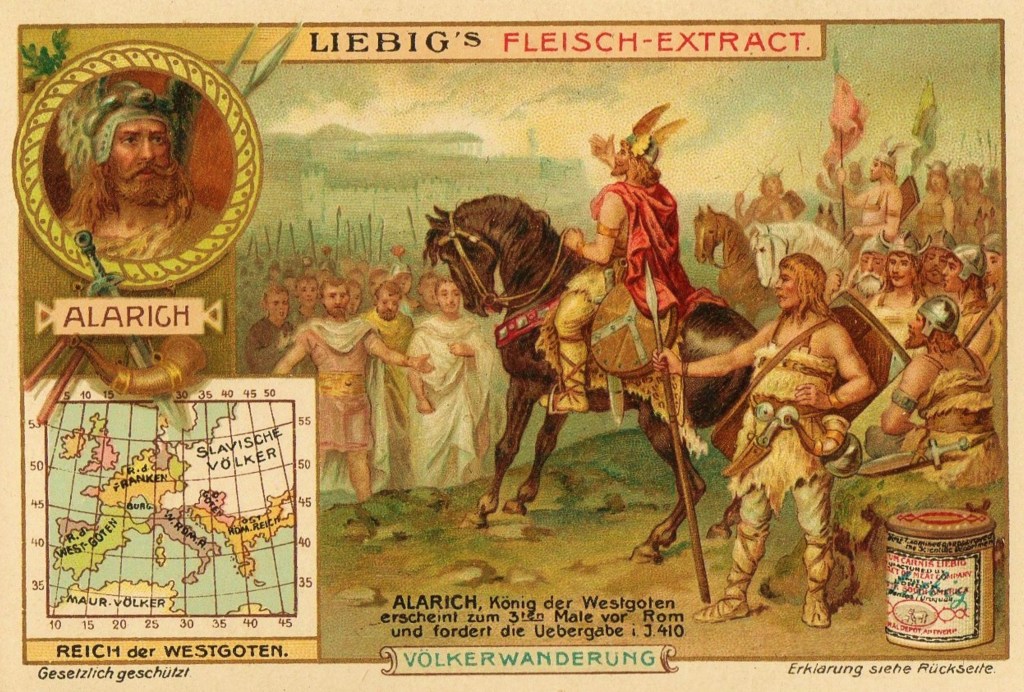

However, David Woods convincingly argues that Zosimus’ original Greek text has been consistently mis-translated and Honorius’ letter was in fact addressed not to Britain but to Raetia, the province north of Liguria. In 410 Alaric the Goth, who had sacked Rome that year, was in Liguria so it seems eminently logical that the citizens of Raetia were warned to get ready to defend themselves. 2

So, if Zosimus was not even writing about Britain, we need to look at the second source used by historians to show that Honorius refused to help Britain in 410. They point to Gildas Bandonicus, a 6th century British monk, who, in his history the De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain), said:

“The Romans therefore informed our country that they could not go on being bothered with such troublesome expeditions ; the Roman standards, that great and splendid army, could not be worn out by land and sea for the sake of wandering thieves who had no taste for war. Rather, the British should stand alone, get used to arms, fight bravely, and defend with all their powers their land, property, wives, children, and, more important, their life and liberty.” 3

Unfortunately, Gildas was not only writing in the 540s, 130 years after the alleged event, he is a notoriously unreliable source with a political agenda; he doesn’t mention Honorius or 410 nor offer any other dateable reference. But, he paints a picture of the weak and cowering Britons helpless against the marauding Picts, Scotts and Saxons begging the Roman Empire for help on multiple occasions; in a second instance:

“… the envoys set out …. to beg help from the Romans. Like frightened chicks huddling under the wings of their faithful parents, they prayed that their wretched country should not be utterly wiped out.” 5

Left to their own defences Gildas writes that the Britons:

“…. abandoned the towns and the high wall. Once again they had to flee: once again they were scattered, more irretrievably than usual; once again there were enemy assaults and massacres most cruel. The pitiable citizens were torn apart by their foe like lambs by the butcher; their life became like that of the beasts of the field.” 6

Gildas’ account, which rather than a history, is a sermon against the behaviour of the ruling classes and religious leaders of his own day, includes references to known events such as the building of Hadrian’s Wall and the development of the “Forts of the Saxon Shore” but he fits these events into the decades between Honorious’ alleged letter in 410 and the time when Flavius Aetius was commander of the Western Roman Army in 433 to 454. Hadrian’s wall was built in 122 and reenforced in 165; the “Forts of the Saxon Shore” were built at different times between around 225 and 285 and were very possibly fortified warehouses rather than part of a defensive military network. Gildas’ history is inaccurate in terms of both content and chronology, the latter by hundreds of years.

Gildas describes in some detail the collapse of British society: weak and incapable of defending itself against the Picts and the Irish but awash with luxury goods and engaged in:

“….. fornication as it is not known even among the Gentiles … Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we must die.”.

And, according to Gildas, they “stupidly” hire three boat loads of Saxons to fight off the Picts and other raiders triggering the beginning of the Anglo Saxon invasion and subsequent settlement of England.

The essence of Gildas’ sermon is that Britain was lost by the Romano British because of their laziness and sinful behaviour. The arrival of the pagan Saxons is, in effect, a punishment from the Christian God.

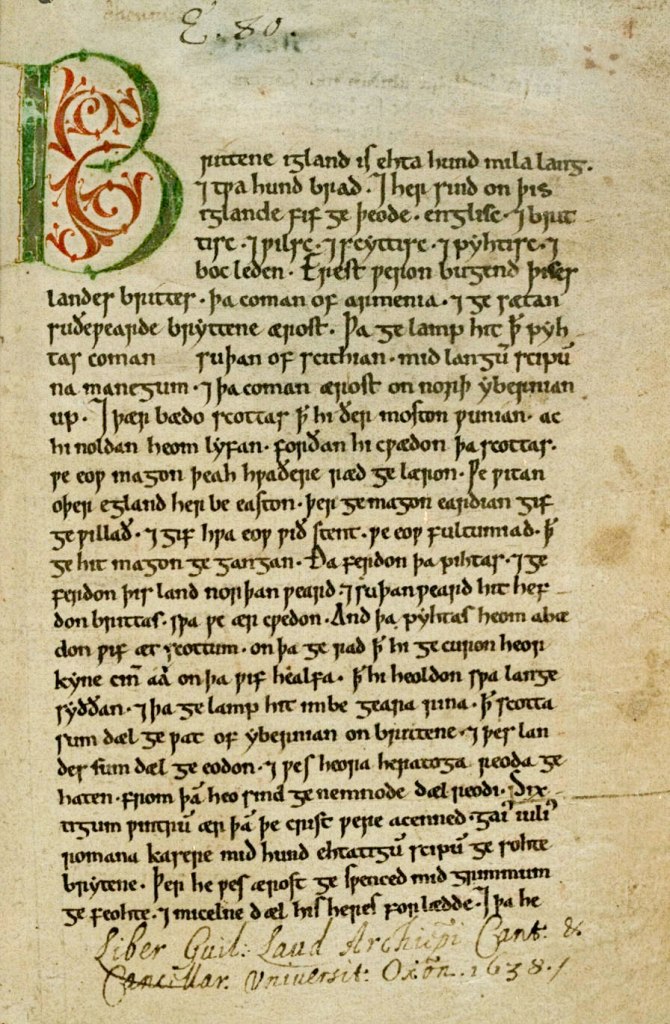

In around 731, Saint Bede (or the Venerable Bede), wrote Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) he used Gildas as his source for the fifth and six centuries.

Bede adds the date 449 for the arrival of the Saxons, Angles and Jutes and tells us they were led by Hengist and Horsa who were direct, and recent dependents of the Norse god Woden.

“It was not long before such hordes of these alien peoples vied together to crowd into the island that the natives who had invited them began to live in terror…..

In short, the fires kindled by the pagans proved to be God’s just punishment on the sins of the nation….

For, as the just judge ordained, these heathen conquerors devastated the surrounding cities and countryside, extended the conflagration from the eastern to the western shore without opposition and established a stranglehold over nearly all the doomed island.” 9

A century and a half later the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, which was first being circulated in around 890 relied heavily on Bede and repeats Bede’s description of the Saxons arrival.

The Chronicle does add that they landed at Ypwinesfleot or Ipwinesfleet which could refer to Ebbsfleet on Thanet.

Consequently Gildas’ account of the fall of Roman Britain including how and when the Saxons arrived was repeated by sources that, on most other matters, were considered reliable and authoritative. In therefore comes as no surprise that until archeologists began to doubt the conventional wisdom regarding this era historians continued to promote the idea that the last Roman left Britain in 410 and the Anglo Saxons poured in in 449.

Events Elsewhere

Roman Britain did not disappear overnight in 410 leading to chaos, conflict and the collapse of all social order but there was plenty of turmoil in the late 4th and early 5th centuries in Britain and across wider Europe.

Barbarian incursions in the 360s culminated with the Barbarian Conspiracy in 367, when Picts, Attacotti, and Scots overran northern and eastern Britain while Franks and Saxons invaded Gaul.

The invaders were eventually repulsed and order restored by Flavious Theodosius who was despatched to Britain by the Emperor Valentinian I.

The Roman infantryman of the 4th century was no longer the legionnaire who conquered western Europe. With their trousers or leggings they look more German than Italian. (see right 10)

In 368 one of Theodosius’ junior officers was Magnus Maximus, a Spaniard, who distinguished himself fighting the barbarian invaders. In 380 he was sent back to Britain as a senior commander and suppressed another invasion of Britain by the Picts in 381.

He became a favourite of his troops and the Romano British so when the British garrison became disillusioned with the Emperor Gratian, they proclaimed Maximus Emperor.

The gold solidi (left) depicting Maximus was one of the last Roman coins minted in Britain.

Maximus subsequently took a large proportion of the British garrison and invaded Gaul. For a brief time he ruled Britain, Gaul and Spain but was executed by his old boss’ son, the Emperor Theodosius I, in 388 following his failure to add Italy to his portfolio.

In 405 the Roman General Stilicho recalled troops from both Britain and Gaul to defend Italy against the Gothic invaders. Stilicho was the power behind the throne of Honorius who had succeeded his father Theodosius in 395 when aged just eleven. In 407 the British garrison proclaimed Flavius Claudius Constantinus, a common soldier, as Emperor Constantine III and he subsequently invaded Gaul with a large contingent of the British garrison. For a short time, he ruled the western edge of the old Roman Empire, Britain, Gaul and Spain, before being defeated and executed in 411 by one of Honorius’ generals.

In 410 Alaric I, King of the Visigoths, sacked the City of Rome. The Goths probably originated in Sweden before, over two or three centuries they migrated south to the southern shores of the Baltic and then down through Europe until they reached modern Poland and Ukraine. In the 4th century they were settled around the Black Sea but in the 320s the Emperor Constantine crossed the Danube and defeated the Goths in a series of battles. He forced them into submission as vassals of Rome.

Fifty years later around 370 the Huns crossed the Volga River and began to attack the Goth’s eastern flank. The Goths had no answer to the Hun’s mounted archers and many moved west until they reached the Danube. This group, who now called themselves the Valiant Goths or Visigoths, called upon the Romans to help them and Valens, the Emperor of the Eastern empire, probably recognising that he had little choice, let them into the empire in 376.

This was never a comfortable situation and within a couple of years the Visigoths who had been starved and exploited by Roman officials and merchants rebelled and began raiding Roman settlements in Thrace; Valens rushed to confront the rebels but he was ill prepared and at the Battle of Adrianople, the Visigoths slaughtered in excess of 10,000 men, two-thirds of the Eastern Empire’s field army and killed the Emperor Valens. It was Rome’s most costly defeat since Publius Quinctilius Varus led three legions to their annihilation in the Teutoburg Forest in the year 9.

Vandals, Alans and Sebum crossed the Rhine between 405 and 407 eventually settling in Gaul, Spain and North Africa. The Franks and Burgundians took control of northern Gaul and Alaric’s Visigoths sacked Rome in 410. The Western Empire was now in real and comparatively rapid decline. the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus was deposed in 476.

The British Garrison in the 5th Century

Despite the various recalls and departures of the military Britain still had a garrison and the various barbarians beyond the wall or on the European mainland had no easy access to rich pickings.

This is likely because the Roman army had long been reorganised into two distinct groups – the strategic field armies (Comitatenses) who, in Britain, were mostly heavy cavalry based at Caerleon and York and the frontier troops (Limitanei) who manned Hadrian’s Wall and the so-called “Saxon Shore Forts” on the east and south coasts. It was only the Comitatenses who had left and, after the death of Constantine III, remained stationed in Gaul. This made sense as the greatest threat to the empire was from the various peoples living along their northeastern and eastern borders.

The British Garrison were probably quite literally the descendants of the legions. Over the four hundred years of Roman Britain the Empire had sent legions and auxiliary units who had been recruited across the empire from Germania to Thrace, Syria and North Africa. Many of these soldiers officially or unofficially married local women and their children were often recruited into the army in the 3rd and 4th centuries.

Another source of Romano-British recruits would have been young men growing up in the coloniae, the official colonies established for retiring soldiers. These included Colchester, Lincoln and Gloucester and York where ex legionnaires received a cash bonus and a land grant to settle; many would have married local women and their sons probably preferred joining the army to life as a farmer.

There is evidence that the Limitanei were still in place as late as 428/9 when they were victorious in a battle against the Picts; this suggests that a military command structure and a way of paying and equipping professional soldiers remained long after 410. Alexander Canduci argues that the Limitanei existed as a coherence force until around 435 or as late as 440.

Canduci believes that there was little or no reason for the Western Empire to cut off Britain or for the Romano British to rebel and distance themselves from the Imperial Court at Ravenna. He believes that the real watershed was the loss of the Province of Africa to the Vandals in 430 and with it the loss of the Western Empire’s “breadbasket”. This would have been an economic catastrophe resulting in Ravenna’s inability to maintain armies, which by this point were mostly mercenary, to defend against barbaric invasions.

Canduci suggests that until about this time the Imperial Court were still sending Roman officials to Britain and the Church in Rome remained in control of appointing British Bishops. Unfortunately, there is no archaeological evidence to support this view but Canduci’s point is that there is also no evidence to refute it. 15

It is worth considering that many of the forts along Hadrian’s wall continued to be occupied into the sixth century. Birdoswald, Housesteads and Vindolanda all show evidence of continued use, ongoing maintenance and refortification. Of course, we cannot be certain who controlled these sites but it is not too far fetched to think that the descendants of the early 5th century Roman British garrisons retained control of the forts providing security to a local population in return for some form of taxation.

Was Britain Isolated after 410?

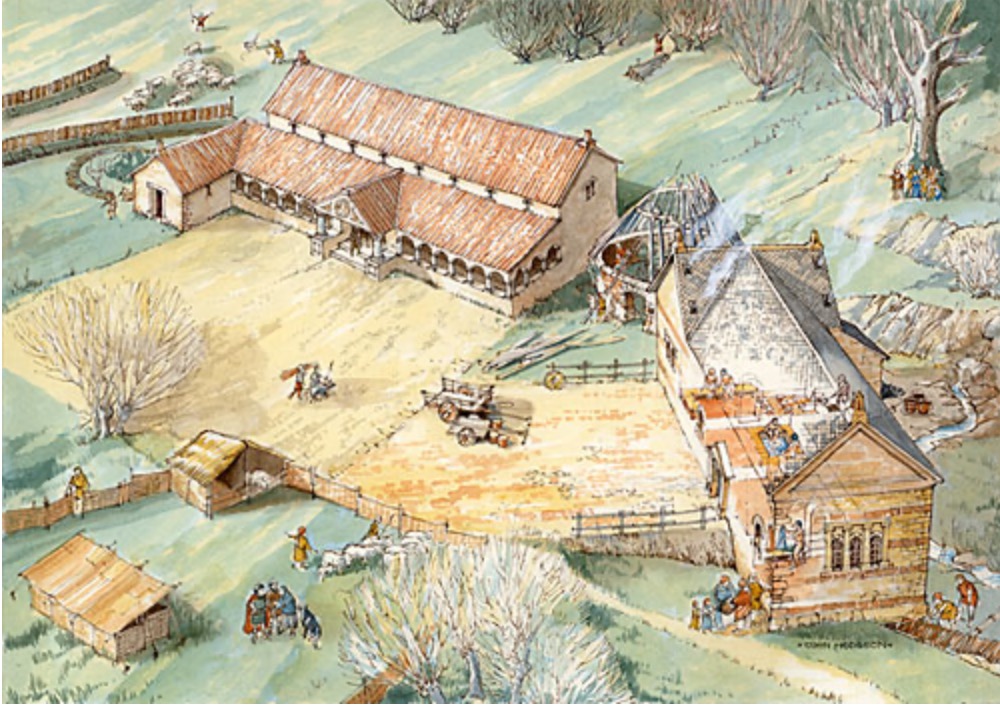

In the 4th century rural Britain away from the frontier zones was booming; wealthy Romano British were investing in enlarging and enhancing their country estates; villa owners were adding rooms with painted wall plaster and elaborate mosaic floors were being laid above hypocaust heating systems. This a period that Guy de la Bédoyère calls “The Golden Age of Roman Britain.” 17

A seemingly typical example of bucolic Roman Britain is modern day Gloucestershire with its two main Roman towns of Colonia Glevum (Gloucester) and Corinium Dobunnorum (Cirencester), the latter being Roman Britain’s second largest town. This was one of the richest parts of Roman Britain with at least fifty villas having been discovered in the Cotswolds.

It was important militarily as it lay on the borders of the troublesome west with a legionary fort at Glevum guarding the Severn Estuary, and which became a colony for veterans in AD 97, .

The Fosse Way ran south through Aqua Sulis (Bath) and connected to the port of Abona (Bristol) and on to Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter); to the north it reached another major hub at Lindum (Lincoln) linking Corinium to the North and East.

The Ermin Way ran West to Glevum (Gloucester) and into Wales whilst to the East it connected Corinium to Londinium (London) and ultimately to Gaul. Akeman Street took soldiers, administrators and traders to Camulodunum (Colchester) the Roman capital of Britain

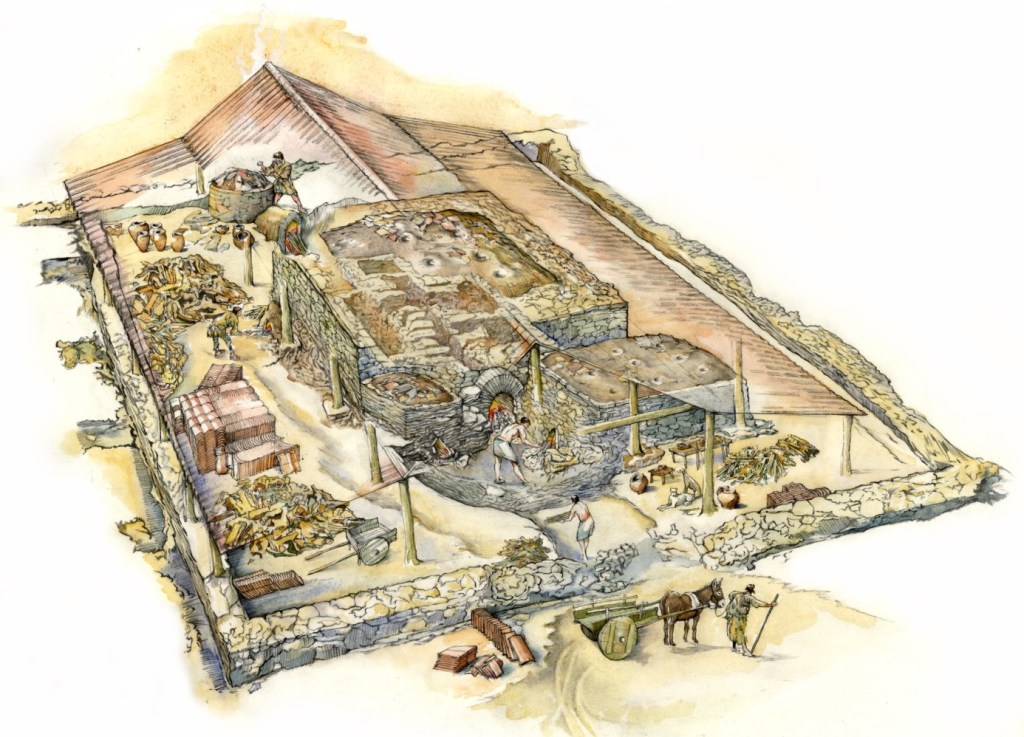

It was a vital centre of industry with iron production in the Forest of Dean and lead mining to the south in the Mendips, limestone and gravel quarrying and extensive potteries distributing product across the province through Corinium.

In addition to military and industrial activity this part of the west country was blessed with rich farmland and many of the villas were at the centre of large agricultural estates.

Remarkably there is increasing evidence that owners continued to invest in these properties well into the fifth century.

The villa at Chedworth, about 8 miles from Cirencester, was originally built around AD 120 and by the end of the fourth century had evolved into a grand country house with three ranges, two courtyards, a bath house and mosaic floors in at least 14 rooms. Recent discoveries at Chedworth suggest that its owners were still enjoying the Roman way of life not just in the 5th century but well into the 6th. Fragments of Palestinian, Cypriot and Turkish amphora dating to the 6th century have been found containing traces of olive oil and wine.

Perhaps most remarkably a mosaic in a room that was excavated in 2017 can be dated to no earlier than 424 and most probably was constructed towards the end of the fifth century 21, long after the Romans are alleged to have abandoned Britain and the well into the so-called Dark Ages.

This tells us that a luxury, Roman style lifestyle was still being enjoyed and trade with the eastern Mediterranean was occurring in the 6th century. The fact that a mosaic industry was still functioning well in to the 5th century shows there must have been industry, commence and quite probably urbanisation as a highly specialist craft such as this could not have existed in isolation.

Professor Alice Roberts points out the significance of this find:

“This is so exciting and it’s unlikely to be unique. It’s unlikely this is the only villa that carries on into the fifth, maybe sixth centuries. We have to go back and look at all the rest. It’s one of those times when we can genuinely say, this is re-writing history.” 22

Chedworth is not the only example of post Roman trade with the Mediterranean. Tintagel on the north Cornish coast, in Roman Dumnonia, was either a high status settlement or a major trading hub in the 6th century.

On the headland archeologists have found evidence of nearly 100 small, rectangular buildings, a shape that is unusual for 5th to 7th century Cornwall. However in 2016 massive stone walls dating to the same period were also discovered suggesting the existence of a high status hall or defensive structure on the site.

The importance of Tintagel is the discovery of over 2,000 fragments of 5th and 6th century pottery and glassware originating from various parts of the Mediterranean world but predominantly from the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium as it is usually called. These same types of pottery have been found in significant quantities at Bantham and Mothecombe in South Devon, South Cadbury and Cadbury Congresbury in Somerset, Dinas Powys in the Vale of Glamorgan and Rhynie in Aberdeenshire.

Bantham seems particularly relevant in the context of understanding late and post Roman Britain as some of the finds date to 475 or even as early as 450 suggesting that trade been the Eastern Mediterranean and the West of Britain was uninterrupted throughout the second half of the 4th and into the 5th centuries. 24 In exchange it is likely that the British were exporting tin, iron and wool to the Mediterranean.

However, it is unlikely that all the Byzantium or Eastern items dating to the 6th century and found in Britain came through trade. The collection of grave goods excavated at Sutton Hoo and at Prittlewell includes many items from the Eastern Mediterranean and as far afield as India and Sri Lanka.

The burials are of elite men who were laid to rest in monumental graves, fully clothed with their weapons and surrounded by vast arrays of valuable and exotic grave goods. The burials date to the late 6th and early 7th centuries. Conventional wisdom has associated these graves with the beginning of Kingship in Anglo Saxon Britain; some historians suggest that King Raedwald, the king of the East Angles, was the warrior buried at Sutton Hoo. Other less significant collections have been unearthed elsewhere that, whilst of a smaller scale, contain similar items.

Helen Gittos 27 puts forward a believable and well argued alternative to these graves containing great, early kings surrounded by luxury goods from Byzantium and further east that were obtain by trade or gift giving. He believes that there is strong case for these men being aristocratic, elite horsemen, knights or equestrians if you like, who had fought as mercenaries for the Eastern Roman Empire. He argues that these men were part of the Foederati recruited by the Emperor Tiberius in 575 to fight in wars on the Eastern Empire’s eastern front.

“Those who returned brought back with them metalwork, and other items including textiles, which were brand new, and distinctive, and not the kinds of things that were part of normal trading networks. They were buried with military equipment and armour associated with their military status, perhaps in part paid for with the annual grants for weaponry, horse equipment and armour they received when serving.” 28

Did Agriculture and Industry Decline?

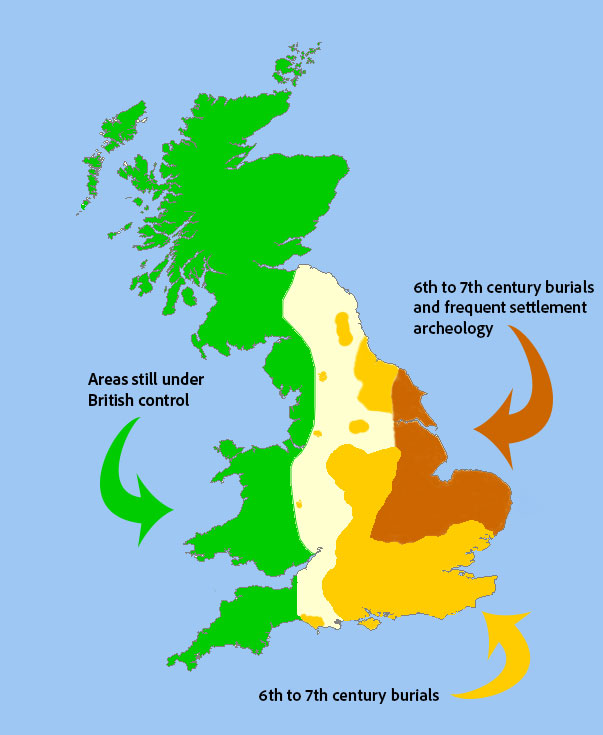

The archeologist, broadcaster, writer and farmer Francis Pryor has been an important voice in the debate of how Britain transitioned from Roman to Anglo Saxon. His book and Channel 4 TV series Britain AD 30 presented the argument that British society gradually evolved from being Romano British to, what became labelled, Anglo Saxon and, most importantly, that the men and women of England who made up the majority of the population of Anglo Saxon Britain were the same people who lived in pre-Roman Iron Age Britain and who had become Romano British.

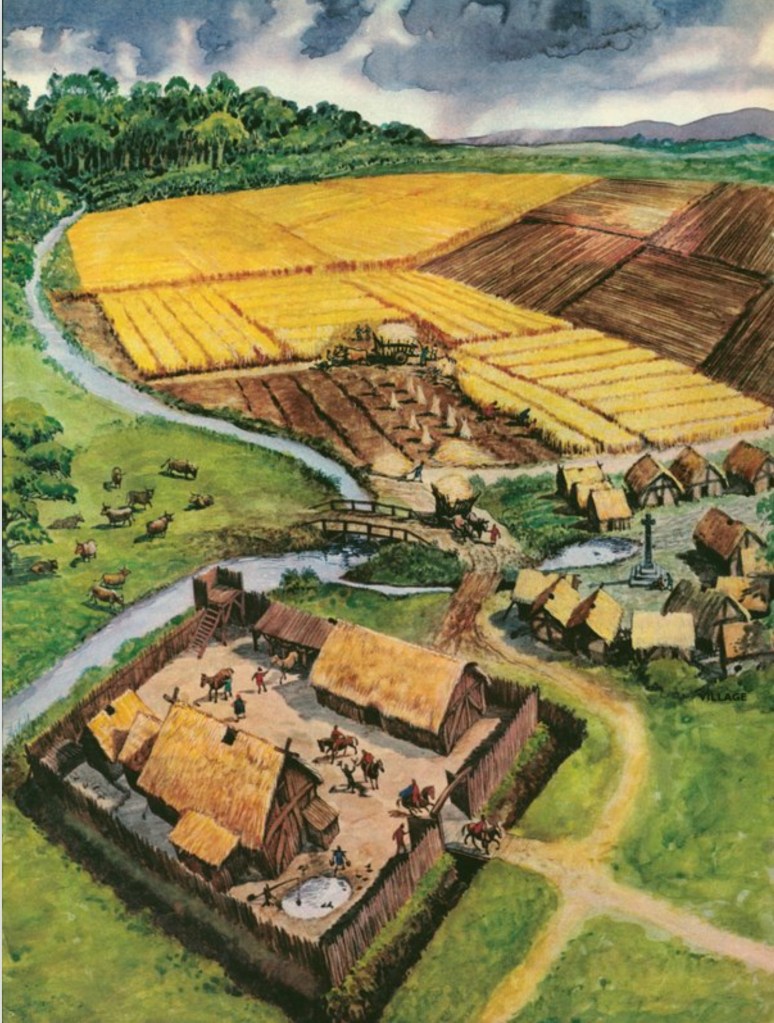

In Pryor’s view the Anglo Saxon invasion was not so much a mass migration of people, violent or otherwise, but more of a gradual invasion of ideas. To support his arguments Pryor points to the continuous occupation of farm land in several areas in eastern England without any signs of violent take over; bearing in mind that any rampaging Angles, Saxons and Jutes would have got here first as they swept through England. Based on field patterns with their associated ditches and hedges and the location of trackways, droves and houses from each era through to and including the Anglo Saxons Pryor sees the landscape being farmed without interruption. Roman buildings respecting Iron Age field patterns and Anglo Saxon houses built on the alignment of Roman ditches.

Elsewhere, archaeologists from Nottingham and Cambridge Universities extracted a five-metre-long sediment core from the River Ure near Aldborough in Yorkshire, Roman Isurium Brigantum. The core revealed a 1,600 year and continuous record of metal production in the town. Within those results the researchers reported that the sample showed low levels of lead and iron production in the 4th to early 5th centuries but then a large increase in iron production in the 5th to mid-6th centuries using the same sources of iron ore and coal as had been used in the Roman period.

This shows that, far from the metal industry in Isurium Brigantum collapsing in 410, it continued without any breaks and increased output until setback by the European wide plague between about 550 and 600. Professor Christopher Loveluck of Nottingham University summaries the implications of this evidence:

“The results show the value of truly interdisciplinary research, linking evidence from archaeological excavations, textual sources and the unique continuous record of metal production at Aldborough, to overturn some long-held notions of when post-Roman industrial collapse occurred in the early Middle Ages” 32

Tin, which was much in demand as a component of pewter was much in demand as a competent in the production of pewter in Europe, the Middle East, Arabia and Persia. Mining continued in Devon and Cornwall and was traded to the Mediterranean probably overland via Gaul and the Rhone River.

Pottery had always been a significant industry in Roman Britain, the Roman Army owned its own potteries and several centres of the industry thrived in the 2nd to 4th centuries. It has long been thought that this industry all but collapsed at the end of the 4th century but this is now being questioned. There is evidence that pottery continued to be produced using Roman technology in the 5th and sometimes into the 6th century in Lincolnshire, Somerset, Dorset, Yorkshire and Hertfordshire. Some of the shards that have been studied reveal designs that were in use in the Romano British period but there is also evidence of Anglo Saxon style cremation urns being made using Roman techniques. 34

It is easy to forget that we are separated from Roman Britain by around 1,600 years so the evidence available for any given facet of 5th century life is not only scattered across the country but as often as not ploughed, built over, robbed out, submerged or otherwise destroyed. This means that most theories are based on relatively small pieces of evidence so we often have to report to common sense to make a best guess of what was happening.

In that context it is worth summarising what seems to have survived Britain’s eviction from the Roman Empire.

Security: given the record of the Picts and Scotts in the last decades of Roman Britain it seems unlikely that they stopped raiding as soon as the Roman military is alleged to have left. Britain was not overrun by people from Ireland or Scotland so along with archeological and historical evidence we can safely say that there were still professional soldiers guarding the northern border and perhaps elsewhere.

- Trade: olive oil and wine continued to be imported into the 6th century.

- Markets: trade only exists where there is a market to buy product so a significant number of people, maybe the tribal elite, must have still been buying wine and olive oil and whatever other luxury goods the traders carried.

- Connectivity & Infrastructure: trade also requires communication, transport, a place to store goods and a place to sell them. The Roman road system remained in use with some forming the basis of modern roads 2,000 years later. Markets would have existed in Iron Age Britain and even if Romano British forums had fallen into disuse markets would have sprung upon to replace them.

- Villas: at least one huge country estate was operating in the west country into the 6th century. (And surely there were many more) Perhaps they were only in the southwest but there is no evidence either way.

Specialist Trades: if society was in the process of collapsing it might be expected that specialist suppliers to the rich villa owners would have been one of the first things to go. A mosaic industry survived in the Cotswolds which not only must have been servicing more than one villa but suggests other specialist industries might of survived.

- Agriculture: farming obviously survived at Chedworth and other villa estates but across the fens and the rich agricultural land of eastern England it not only survived but was uninterrupted with farm building styles evolving from Iron Age to Roman to Anglo Saxon in the same farmyards. As discussed below we know of at least 100,000 Romano British farms that were unconnected to villa estates. There is evidence that wool and textiles were being exported.

- Industry: iron, lead tin mining, smelting and working continued uninterrupted. Locally distributed pottery was still being made using Roman techniques and technology.

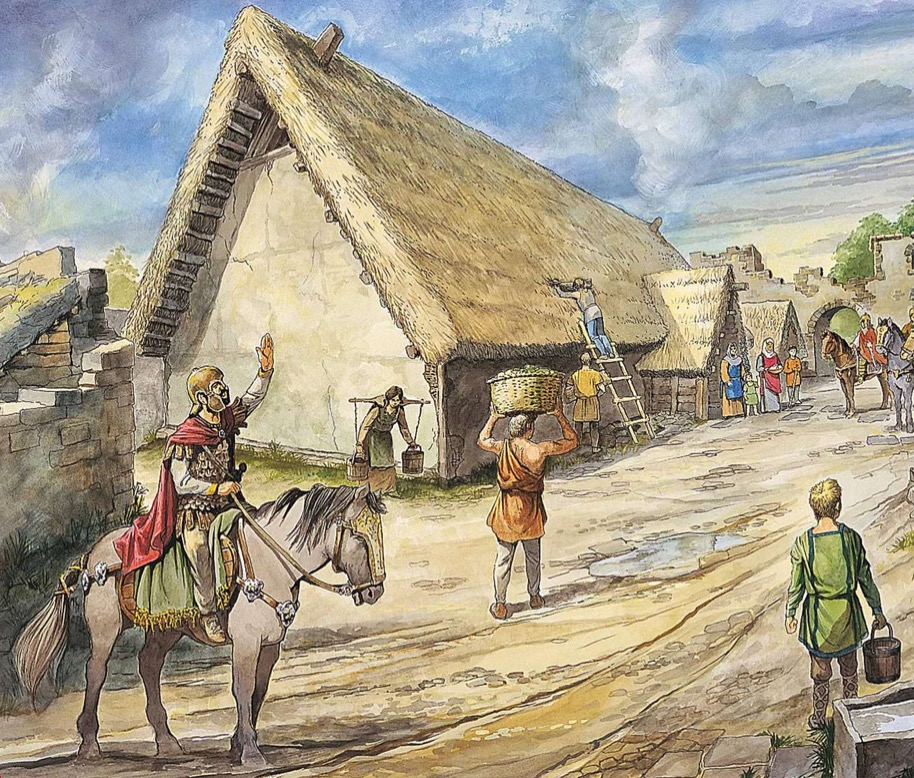

Post Roman Britain was different than Roman Britain. Industry probably became more localised, urban centres declined but rural life seems to have continued much as it always had. Realistically life probably changed very little for the average farmer, small holder, farm worker or agricultural slave from the Iron Age right through to Post Roman Britain.

Romano-British or Just British?

The very term “The Dark Ages” which is used to describe the first two hundred years after the collapse of Roman rule, promotes the idea that after 410 the British regressed, from some sort of cultural high under the Romans, to become less cultured, more ignorant and less sophisticated. Under this, long accepted, theory Britons deserted the towns and returned to the countryside to live in muddy squalor until wiped out, or pushed into Wales or Cornwall, by the Saxon invaders.

The strategic field armies, the Comitatenses, left with Constantine III in 407 and whilst it is highly unlikely that Honorius told Britain to go it alone in 410 the whole provincial administration had probably ceased to function by about that date.

In the early 5th century there was a Romano British population of around 4 million; some people were still living very Roman lifestyles with under floor heating, mosaics and imported wines but de la Bédoyère 37 thinks there were never more than 40,000 people living in villas.

It appears that the population in towns was declining, probably accelerated by the collapse of the political and administrative system so by 410 the elite people still living in villas were a tiny minority but who, other than the military, left the largest archaeological footprint in the landscape.

The whole island was never conquered or occupied and very few of the Romans who came to Britain were Italians. The British tribal elite, who probably owned many of the villas, appear to have aspired to adopt Roman culture but they had few, if any, Italian Romans to mimic. Their idea of Roman culture would have been based on the military colonies, the trading centre of London and the spa town of Bath but, according to the British Museum,:

“These models themselves drew heavily on prototypes in Roman France and the Rhineland. Consequently, Romano-British towns and villas, for example, were British reinterpretations of Gallo-Roman adaptations of Italian ideas. These places were modelled on Roman Gaul and the Rhineland .” 39

The population of Roman Britain had always been predominantly rural, so even if 200,000 people were still living in urban centres that still left around 3.5 million people living in the countryside. Mining, pottery, tile making, metal working and forestry were usually rural industries but the majority of rural Romano British were living and working on farms.

It is estimated that there were 2,500 villas, often centred on large agricultural estates and many Britons would have worked on these estates as slaves, employees or tenants. However, the number of these stately homes and their managed farms pales into insignificance when compared to the 100,000 Romano British farming settlements that have already been found in Britain.

Many of these were located far from any towns or villas, often remote and probably quite detached from mainstream Roman Britain and some were part of extensive settlements, Max Adams describes one such settlement on Salisbury plain:

“At Charlton Down, on the far northeastern edge of Salisbury Plain, at least 200 house compounds can be identified from their grassy earthworks, covering no less than 26 hectares – the size of a substantial Roman Town. ……..Charlton must have been a buzzing, productive community – larger, more industrious and more populous than any settlement, anywhere in Britain during the 300 years after Rome’s fall.” 41

These farming families are likely to have embraced new Roman introduced, crops such as cabbages, onions, leeks, and turnips, new markets such as the Roman army and urban centres and new technology such as a better plough when they could afford to invest. New crops, markets and enhanced technology might have made farms of all sizes more productive but it would be surprising if British farmers and farming altered dramatically across the many decades of Roman rule.

These farmers presumably learnt enough vulgar latin to deal with administrators, tax gatherers and non-British buyers but they were probably not people who were, or wanted to be, Romanised, they were farmers who lived and worked within farming communities probably speaking their local language and dialect whilst carrying on farming the same land in a similar way to their forefathers.

A post Roman grave marker found near Ffestiniog in North Wales.

The Inscription reads – “Cantiori Hic Jacit Venedotis Cive Fuit Consobrino Magli Magistrati“

“Cantiori lies here; he was a citizen of Gwynedd, a cousin of Maglus the magistrate”

It shows that Latin and Roman administrative titles survived the departure of the Romans. 43

The Romano British in the settled south are likely to have spoken Vulgar Latin, similar to the Latin dialect spoken in Gaul that eventually evolved into French but we cannot know if this became the predominant first language but, for the farming community at least, it seems more likely that they continued to speak their native Brythonic, the Celtic language from which Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Cumbria and possibly Pictish is derived.

Despite the time the Romans were in Britain it seems equally unlikely that the attitudes, language, religious beliefs, tribal loyalties, way of life, i.e. the core culture of the huge rural population changed significantly between AD 43 and AD 410.

If we have found 100,000 Romano British farms there must be far more lying hidden under the suburban sprawl of modern towns or ploughed out by modern agriculture or still waiting to be discovered. These farms following the British Iron Age model, would have been occupied by an extended, multi generational family, perhaps between 10 to 20 individuals on each farm. That is 1 to 2 million Romano British farmers and their families on the 100,000 known farms and it would be easy to argue a case for doubling that estimate to account for the farms we have not yet found.

The Romans never appear to have seen the British as truly Romanised; a wooden tablet found at Vindolanda refers to the British as Brittunculi, which roughly translates as nasty little Britons or wretched natives; we cannot know whether this derogatory term refers to northern or all Britons or even Britons serving in the Roman army. John Lambshead writes:

“In short, after three centuries of Romanisation one gets a distinct impression that educated Romans still regarded Britons as semi-barbarians, unlike their close cousins from Gaul whose elite were civilised and respected citizens.” 44

It is probable that this was a two way street and that the majority of the population of Britain was never Romanised, spoke a pre-conquest language, took whatever advantages Rome had to offer but lived in much the same way as their Iron Age ancestors.

England Becomes Englisc

Gildas, Bede and everyone who subsequently promoted their ideas of an Anglo-Saxon invasion were coming up with an easy and simple explanation how Roman Britain became Anglo Saxon Britain in a comparatively short time.

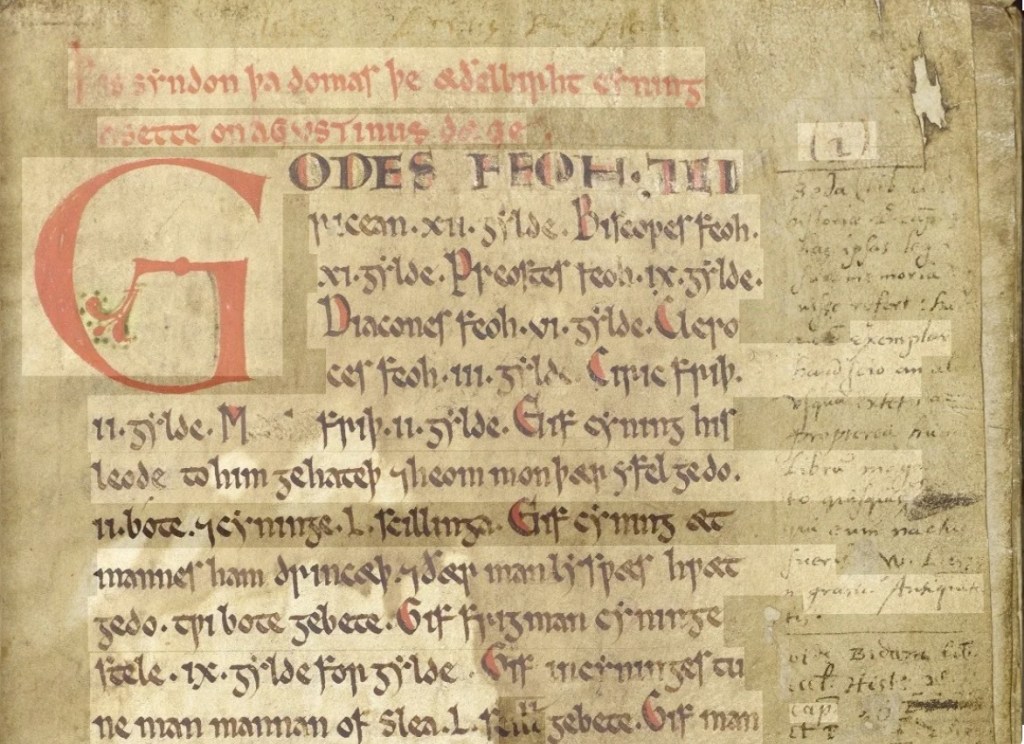

The first document written in Old English, the language of Anglo Saxon Britain, was the Law Code of Æthelberht of Kent written in about 600. It seems that Old English was in wide use by the middle of the 6th century and it appears to be hardly influenced by other Vulgar Latin or Brythonic, the two languages we assume the British were speaking in the mid 5th century. Invasion seems an easy answer but as previously mentioned there is absolutely no evidence of settlement burning, battlefield graveyards, sacked and ruined towns or any of the other traces that invasion should leave in the archeological record.

“No British town or fort of the late fourth or early fifth century has yielded any proof of having been comprehensively razed. ……… No Roman town in Britain was comprehensively abandoned in a hurry. Building materials, metalwork, furniture, pottery and domestic fittings continued to be recycled by inhabitants. …… Britons did not, so far as one can tell, run away en masse” 46

It is possible that Gildas and Bede were right in saying that a British King paid Saxon mercenaries to fight off the Picts and Scots and having done so stayed and defeated the lazy Britons to claim Britain for the themselves. It is not unreasonable to think that this story is partly true and that Jute, Angle and Saxon mercenaries were employed to help fight off the raiders from north of the wall and Ireland but that afterwards they stayed as settlers rather than as conquerors.

Another interesting idea is that the Forts of the Saxon Shore and Count of the Saxon Shore (comes litoris Saxonici) were not describing defending Britain from the Saxons but that Saxon mercenaries were stationed in the Forts under the command of the comes litoris Saxonic. Archeological finds, including Romano-Saxon pottery and the type of male jewellery associated with Angles, Jutes and Saxons has been found in the vicinity of the forts. 47

By the 5th century a significant proportion of the Roman army were men from outside the borders of the Western Empire; Olympiodorus of Thebes, an Egyptian historian and Roman diplomat writing for the Emperor of the East in the early 5th century, said that there was a heavy reliance on “barbarian” allies, foederati, and there is archeological evidence that substantial numbers of gold coins were flowing from Italy to both sides of the lower Rhine in the 5th century. 48

There were German speaking soldiers in many different parts of Britain and at different times. Many german speaking auxiliary units served on Hadrian’s Wall. Cremation cemeteries have been found near Roman towns, forts and roads containing pottery made in Britain but in a German style suggesting it was marketed to German soldiers. 49

All of this suggests a possible scenario of many German speaking soldiers being posted to Britain over the life of the occupation who, like all soldiers everywhere in any era, spent much of their free time in the settlement that grew up outside the walls, the vicus. If a German speaking auxiliary unit was in the fort it is certain that the men and women servicing the soldiers would have soon learnt their language. Some soldiers would have “married” local women leaving them with their children when they were posted elsewhere but others would have retired in Britain and at the end of the occupation many were just left here. These settlements could have been the seeds from which more permanent and German speaking settlements grew.

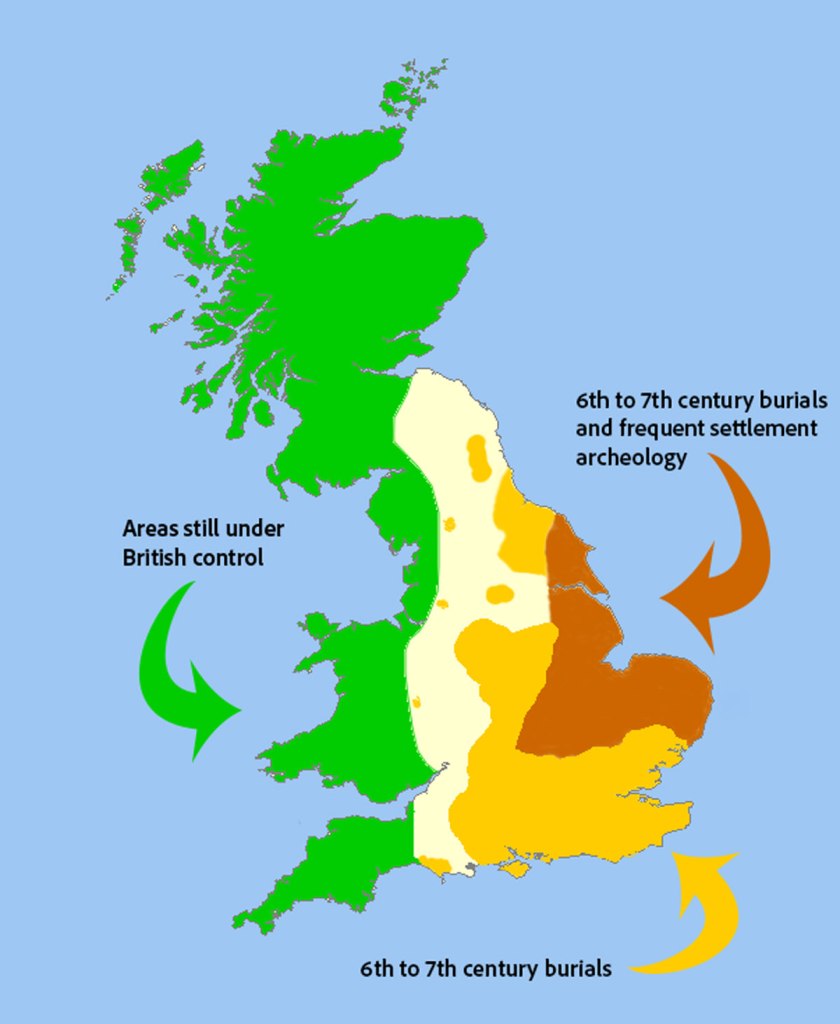

We begin to find archaeological evidence of different cultural practices such as cremation burials and grave goods in eastern British rural settlements from as early as 430. These were both typical Saxon customs that had not recently been seen amongst the Britons.

The evidence found to date does not support a single migration model. The end result is not disputed, by the 6th century there are significant numbers of Saxons, Jutes, Angles and other Germanic or European people in what is now England and it would be rash to argue for a single answer for how they cameo be here.

Isotope and DNA analysis has not been conclusive but it suggests that some 5th and 6th century settlements in various parts of Britain had a mixed population. Most people were raised locally, a small minority came from the Mediterranean (perhaps slaves) and some from continental Europe and or Scandinavia. The results of isotope analysis for the extensive Anglo Saxon or Anglian settlement at West Heslerton suggests that the migrants from Scandinavia or Germany came over several generations and that 20% of the population were Anglian migrants and 80% local Britons. 51

It was a large, 220 building, settlement founded by local people who had probably farmed the land in the Roman ere but that adopted the ideas that are associated with Anglo Saxon Britain such as building styles, burial practices, jewellery design and fabrication and farming. One also assumes that by sometime in early 6th century they were speaking Old English, a derivative of Old German.

However, other historians suggest that both man and female Germanic immigrants arrived and found rural areas that were deserted or semi-deserted. Here they founded settlements where they lived with limited contact with the Britons. Under this model East Anglia may have already formed a distinct Germanic identity by the end of the 5th century.

Conclusion

The transition from Roman Britain to Anglo Saxon Britain is complicated, history always is and there are no simple answers on how and when it happened. We are pretty clear on when Britain was Roman and equally sure that it became, what we call Anglo Saxon: what happened in between is unclear.

Firstly, the term Anglo Saxon Britain is a distraction as unlike Roman Britain it was not a region occupied by a foreign regime and kept under military control. The Jutes, Angles and Saxons didn’t meet at some huge conference in the 5th Century and decide to invade or settle Britain and when they got here there is no credibility to the idea that they conquered the place by defeating and evicting the native Britons..

Some probably came by invitation, some with the Roman Army and some were descendants of the soldiers on the walls and in the forts. There were probably a few raiders, opportunists and pirates and many came as peaceful settlers fleeing a chaotic post Roman Europe and or looking for new land to farm.

In total there were enough to spread far and wide, assimilate into British society, marry into British families and strongly influence the exiting culture. Others came as family groups and settled in the spaces between the old occupied Roman British farming communities, here they developed a distinct identity and in time this spread into Brythonic communities.

Left: Anglo Saxon farm 53

But, non of the alternative or combined models really explain how a Germanic language and culture became dominant in such a short time.

Britain was culturally vulnerable post Rome as the culture of the man and women in fields was fundamentally Iron Age with Roman influence. I am reminded of my time in the Philippines where people used to say that its culture was a blend of 400 years in the convent and 50 years in Hollywood reflecting the Spanish and then American occupation of the islands. Max Adams argues that the Briton’s eager and rapid adoption of Anglo Saxon culture was more a rejection of Roman culture than a new found love of all things Saxon or Jute.

John Lambshead puts forward another explanation which could be overlaid on Max Adam’s thoughts or the idea that Britain was culturally vulnerable. He believes that the Germanic warriors moved into existing farming settlements displacing the British owners, not by eviction or slaughter but by taking ownership of the land and forcing the Britons into working that land as labourers or slaves.

This model explains how, as the culture of the land owners, Saxon culture became predominant and of higher status to Brythonic British. It also paves the way for the creation of the hierarchical society that we know existed by the time of the petty Saxon kingdoms. This idea also allows Britons to become Anglo Saxon as within a single generation of mixed marriages and the adoption of a higher status culture it would not have been about ethnicity or regional origin. Lambshead writes:

“What defined a ‘Saxon’ as opposed to as “Welshman’ was purely a matter of culture. One was a Saxon if one spoke Old English, dressed as a Saxon, used Saxon artefacts and behaved as a Saxon. early medieval culture lacked a bureaucracy recording peoples’ past family histories: only the elite families had ancestors beyond living memory.” 55

Genetically the British have a complicated ancestry that reflects the mix of people who have migrated here via continental Europe since the last ice age. In Eastern England there is plenty of Anglo-Saxon DNA but not enough to suggest they arrived and slaughtered the Britons, it is probable that however they got here, most migrants were males who married local women, an idea that’s supported by finding 40% Anglo Saxon DNA in some areas.

Dr Garrett Hellenthal explains:

“The majority of eastern, central and southern England is made up of a single, relatively homogeneous, genetic group with a significant DNA contribution from Anglo-Saxon migrations (10-40% of total ancestry). This settles a historical controversy in showing that the Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations.” 56

We cannot be sure how the Germanic people found their way to Britain or how their culture and language became dominant but we can be certain that starting in the early to mid 5th century the old Roman province of Britannia, saw the arrival of a significant number of Jutes, Angles and Saxons from northwest Germany and Denmark.

England and to a greater or lesser degree Britain was politically and culturally dominated by the descendants of these people and of Britons who adopted what we now see as Anglo Saxon culture and a language derived from Old German that we call Old English. This mix of Danes, Germans and Britons became the English.

Footnotes

- Alexander Canduci (2022) The Roman Withdrawal from Britain – 410 or 435? A Fresh Perspective. Canduci-202 ↩︎

- David Woods (2021) On the Alleged Lettersof Honorius to the Cities of Britain in 410. Woods-2021 ↩︎

- Michael Winterbottom (1978) Gildas: The Ruin of Britain and Other Works, edited and translated. Winterbottom-1978 ↩︎

- Kevin F. Kiley (2022) An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of the Uniforms of the Roman World. Dayton Ohio: Lorenz Books ↩︎

- Winterbottom (1978) ↩︎

- Winterbottom (1978) ↩︎

- An artist’s reconstruction of Poltross Burn milecastle on Hadrian’s Wall © Historic England (illustration by Peter Lorimer) Hadrians-Wall ↩︎

- Medieval Cronicles. Top 10 Steps Towards the Creation of England Medieval-Chronicles ↩︎

- Bede (1990) Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price, revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin Random House ↩︎

- Kevin F. Kiley (2022) An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of the Uniforms of the Roman World. Dayton Ohio: Lorenz Books ↩︎

- Herbert Booker (1901) Aetius, Alarich, Atilla, Geiserich, Odoaker and Theoderich Trading Cards Booker-1901 ↩︎

- © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative-Commons. – British-Museum-Valens ↩︎

- Deborah Croker (2020) 20 great memories of Portchester Castle over the years Portchester ↩︎

- Northeast Museums Arbeia ↩︎

- Alexander Canduci (2022) The Roman Withdrawal from Britain – 410 or 435? A Fresh Perspective. Canduci-2022. ↩︎

- A reconstruction showing the timber building built on the site of the north granary in the 5th century © Historic England (illustration by Philip Corke) Birdoswald ↩︎

- Guy de la Bédoyère (1999) The Golden Age of Roman Britain. Stroud: Tempus ↩︎

- Corinium Museum Roman-Corinium ↩︎

- Sasha Trubetskoy (2017) Roman Roads of Britain. Trubetskoy-2017 ↩︎

- The Past (2022) Chedworth Roman Villa, a drawing by Tony Kerrins. The-Past-2022 ↩︎

- Martin Papworth (2023) Back to Chedworth and the 5th century mosaic of Room 28 Papworth-2023 ↩︎

- Alice Roberts as quoted in the Daily Mail (2024) Rewriting the history of life in Britain after the Roman Empire: 5th century mosaic at a villa in Gloucestershire proves sophisticated life continued long into the Dark Ages, experts say. Daily-Mail-2024 ↩︎

- English Heritage. Tintagel ↩︎

- Maria Duggan – Internet Archaeology (2016) Ceramic Imports to Britain and the Atlantic Seaboard in the Fifth Century and Beyond. Duggan-2016 ↩︎

- The British Museum. Replica of the Sutton Hoo helmet with leather lining. British-Museum-Helmet ↩︎

- The British Museum (2011) The Byzantine silver bowls in the Sutton Hoo ship burial British-Museum-2011 ↩︎

- Dr Helen Gittos is a Fellow and Tutor in Medieval History at Balliol College and Brasenose College. University-Oxford ↩︎

- Helen Gittos (2025) Sutton Hoo and Syria: The Anglo-Saxons Who

Served in the Byzantine Army? Gittos-2024 ↩︎ - Roger Massey-Ryan. Iron Age Settlement at Lofts Farm, near Maldon, c.850 BC Massey-Ryan ↩︎

- Francis Pryor (2004) Britain AD, A Quest for Arthur, England and the Anglo-Saxons. London: Harper Collins ↩︎

- Dr. John Hodgson. Whitehall Roman Villa and Landscape Project John-Hodgson ↩︎

- University of Nottingham Press Release (2025) Changing the narrative on the ‘Dark Ages’ – earth-core evidence reveals British economy did not collapse on departure from Roman Empire and a Viking-Age industrial boom Nottingham-Uni-2025 ↩︎

- Roman Pottery Kiln Replica at Vindolanda Roman Fort Vindolanda-pottery ↩︎

- Caitlin Green (2016) Romano-British pottery in the fifth- to sixth-century Lincoln region Green-2016 ↩︎

- A Landscape of Curiosities: The Priors Hall Roman Villa Estate Priors-hall ↩︎

- Kevin F. Kiley (2022) An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of the Uniforms of the Roman World. Dayton Ohio: Lorenz Books ↩︎

- Guy de la Bédoyère (2013) Roman Britain A New History (revised edition). London: Thames & Hudson ↩︎

- Roman Britain, Relative degrees of Romanisation. Wikipedia-Romanisation ↩︎

- British Museum. Roman Britain: a consideration of the process of Romanization in Britain British-Museum-Romanisation ↩︎

- Cecily Marshall (2017) Drawing of a Roman farmstead at Great Glen. Cecily-Marshall ↩︎

- Max Adams (2021) The First Kingdom. London: Apollo Books, Head of Zeus Ltd. ↩︎

- The Romans in Britain. Farming and Agriculture. Roman-Plough ↩︎

- Cantiorix Inscription Cantiorix-Inscription ↩︎

- John Lambshead (2022) The Fall of Roman Britain. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword History ↩︎

- Æthelberht’s Code, c.600 CE Aethelberhts-Code ↩︎

- Max Adams (2021) The First Kingdom. London: Apollo Books, Head of Zeus Ltd. ↩︎

- William Bakken (1994) The End of Roman Britain: Assessing the Anglo-Saxon Invasions of the Fifth Century Bakken-1994 ↩︎

- Nico Roymans (2017) Gold, Germanic foederati and the end of imperial power in the Late Roman North. Roymans (2017) ↩︎

- William Bakken (1994) The End of Roman Britain: Assessing the Anglo-Saxon Invasions of the Fifth Century Bakken-1994 ↩︎

- Weald and Downland Museum anglo-saxon-hall-house/ ↩︎

- West Heslerton: The Anglian Settlement. West-Heslerton ↩︎

- A reconstruction by Peter Dunn of an Anglo-Saxon Royal hall at Yeavering, Northumberland © Historic England Archive Anglo-Saxon-Hall ↩︎

- Anglo-saxon-farm ↩︎

- Current Archeology Exploring Anglo Saxon Settlements Bishopstone-Settlement ↩︎

- John Lambshead (2022) The Fall of Roman Britain. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword History ↩︎

- The first fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles (2015) Genetic-Map ↩︎

- Current Archaeology (2014) Exploring Anglo-Saxon Settlement Current-Archaeology ↩︎

Other Sources and Further Reading

- Guy de la Bédoyère (2013) Roman Britain A New History (revised edition). London: Thames & Hudson

- Guy de la Bédoyère (1999) The Golden Age of Roman Britain. Stroud: Tempus

- Guy de la Bédoyère (2024) Populus: Living and Dying in the Wealth, Smoke and Din of Ancient Rome. London: Abacus Books

- Guy de la Bédoyère (2020) Gladius: Living, Fighting and Dying in the Roman Army. london: Little, Brown

- Francis Pryor (2003) Britain BC. London: Harper Collins

- Francis Pryor (2004) Britain AD, A Quest for Arthur, England and the Anglo-Saxons. London: Harper Collins

- Timothy Venning (2012) If Rome Hadn’t Fallen – What Might Have Happened if the Western Empire had Survived. Barnsley: Pen & Sword

- Kevin F. Kiley (2022) An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of the Uniforms of the Roman World. Dayton Ohio: Lorenz Books

- Bede (1990) Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price, revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin Random House

- Max Adams (2021) The First Kingdom. London: Apollo Books, Head of Zeus Ltd.

- John Lambshead (2022) The Fall of Roman Britain. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword History

- David A.E. Pelteret (2001) Slavery in Early Medieval England. Woodbridge: Boydell

- Simon Webb (2024) The Forgotten Slave Trade. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Book

- Jean Andreau and Raymond Descat (2006) The Slave in Greece and Rome (Wisconsin Studies in Classics) Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press

- Charles Freeman (1999) The Greek Achievement. London: Allen Lane

- Mary Beard (2015) SPQR A History of Ancient Rome. London: Profile Books

- Mary Beard (2024) Emperor of Rome. London: Profile Books

- Mary Beard (2008) Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town. London: Profile Books

- Keith Bradley (1994) Slavery and Society at Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Jérôme Carcopino (2004) Daily Life in Ancient Rome. London: The Folio Society.

- J.P.V.D. Balsdon [editor] (1965) The Romans. London: C.A. Watts & Co

- Nigel Rodgers (2008) Ancient Rome. London: Hermes House

- Peter Jones (2013) Veni, Vidi, Vici: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Romans But Were Afraid to Ask. London: Atlantic Books

- Jo-Ann Shelton (1997) As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Robert Knapp (2011) Invisible Romans: Prostitutes, Outlaws, Slaves, Gladiators, Ordinary Men. London: Profile Books

- Emma Southon (2020) A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: Murder in Ancient Rome. London: Oneworld Publications

- Harold Whetstone Johnston (1903) The Private Life of the Romans: Exploring Roman Daily Life and Customs in Ancient Civilization Kindle Edition.

- Alexander Canduci (2022) The Roman Withdrawal from Britain – 410 or 435? A Fresh Perspective. Canduci-2022

- David Woods (2021) On the Alleged Lettersof Honorius to the Cities of Britain in 410. Woods-2021

- Martin Papworth (2017 – 2020) Chedworth Roman Villa Excavation Blog. Papworth-2017-20

- Damian A Pargas and Juliane Schiel (editors) (2023) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery throughout History. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan The Palgrave Handbook

- Noel Lenski and C. Cameron (2019) Framing the Question: What Is a Slave Society? Lenski-2019

- W. O. Blake (1861) Slavery and the Slave Trade, Ancient and Modern, The Forms of Slavery that Prevailed in Ancient Nations, Particularly in Greece and Rome. Columbus, Ohio, H. Miller Blake-1861

- Sir Christopher Hawkins (1811) Observations on the Tin Trade of the Ancients in Cornwall Hawkins-1811

- Project Ancient Tin (2023) Tin-2023

- Trevor Davidson (2024) Culture, politics, and economics: Alcohol and the dynamic social environment of Celtic Europe Davidson-2024

- Karim Mata (2019) Iron Age Slaving and Enslavement in Northwest Europe Mata-2019

- Bettina Arnold (1999) Drinking the Feast: Alcohol and the Legitimation of Power in Celtic Europe Arnold-1999

- Barry Cunliffe (1985) Slaves, Wine and the Roman Conquest Cunliffe-1985

- Vincent J Rosivach (1987) Autochthony and the Athenians Rosivach-1987

- Jason Paul Wickham (2014) The Enslavement of War Captives by the Romans to 146 BC Wickham-2014

- Eleanor G. Huzar (1962) Roman-Egyptian Relations in Delos Huzar-1962

- Philostratus (translated by Frederick Conybeare 1912) The Life of Apollonius of Tyana Conybeare-1912

- Olga Pelcer-Vujačić (2019) Slaves and Freemen in Lydia and Phrygia in the Early Roman Empire Vujačić-2019

- Walter Scheidel (2024) Slavery’s Rome Scheidel-2024

- A. B. Bosworth (2002) Vespasian and the Slave Trade Bosworth-2002

- Laurie Venters (2019) Recovering Runaways; Slave Catching in the Roman World Venters-2019

- Guy D. Middleton (2023) The Horror of Pompeii. Middleton-2023

- Lincoln H. Blumell (2007) Beware of Bandits Banditry and Land Travel in the Roman Empire Blumell-2007

- Susan Treggiari (1975) Jobs in the Household of Livia Treggiari-1975

- Jon Gauthier (2013) Marcus Aurelius and slavery in the Roman Empire Gauthier-2013

- Greek and Roman Authors on LacusCurtius – “A good number of these classical texts by ancient authors, whether in the original language or in translation, are not to be found elsewhere online.” Penelope

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.