In 1810 a slight-figured, personable, young English naturalist travelled northwards from Cape Town in a huge 7,242 km loop into what is now the Northern Cape and beyond before returning via modern day Port Elizabeth and the Garden Route to Cape Town in 1815. He travelled about the same distance as Cape Town is from Alexandria in Egypt.

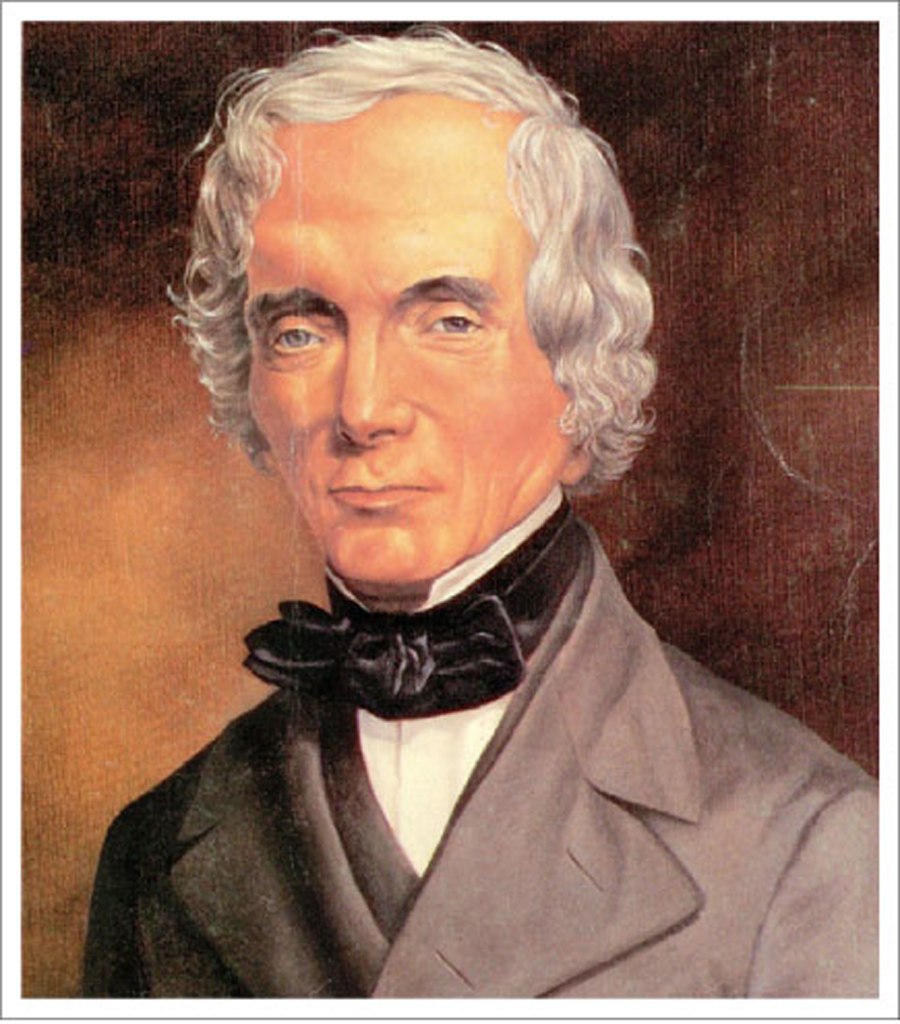

William John Burchell may have been the greatest explorer-naturalist in Africa in the 19th century collecting 63,000 specimens and recording, in colourful and highly readable detail, not just his observations of the natural world, but of the indigenous people of Southern Africa before the subsequent waves of immigrants pushed beyond the old boundaries of the Cape Colony and changed everything.

His great journey is well documented not just by himself but by many other writers over the years; however, I am most interested in his first encounters with the large mammals of the continent and the creatures that two hundred years later still bear his name.

The Cape Colony

When William Burchell finally stepped onto African soil the Cape Colony had been back in British hands for four years, but like the Dutch before them, they had no particular interest in Southern Africa other than holding onto Cape Town and its immediate hinterland as a secure anchorage, resupply depot and staging post for ships sailing between Britain, India and the east. It was the maritime equivalent of motorway service station.

Within a few days of landing in November 1810 he is exploring everywhere within walking or riding distance of Cape Town, and is astounded by what he finds:

“To give some idea of the botanical riches of the country, I need only state that, in the short distance of one English mile, I collected in four hours and a half, one hundred and five distinct species of plants, even at this unfavourable season ; and I believe that more than double that number may, by searching at different times , be found on the same ground.”

Over the following weeks and months he continued to explore the hinterland of the colony and carried out expeditions to the outlying villages of the colony constantly observing, collecting and drawing.

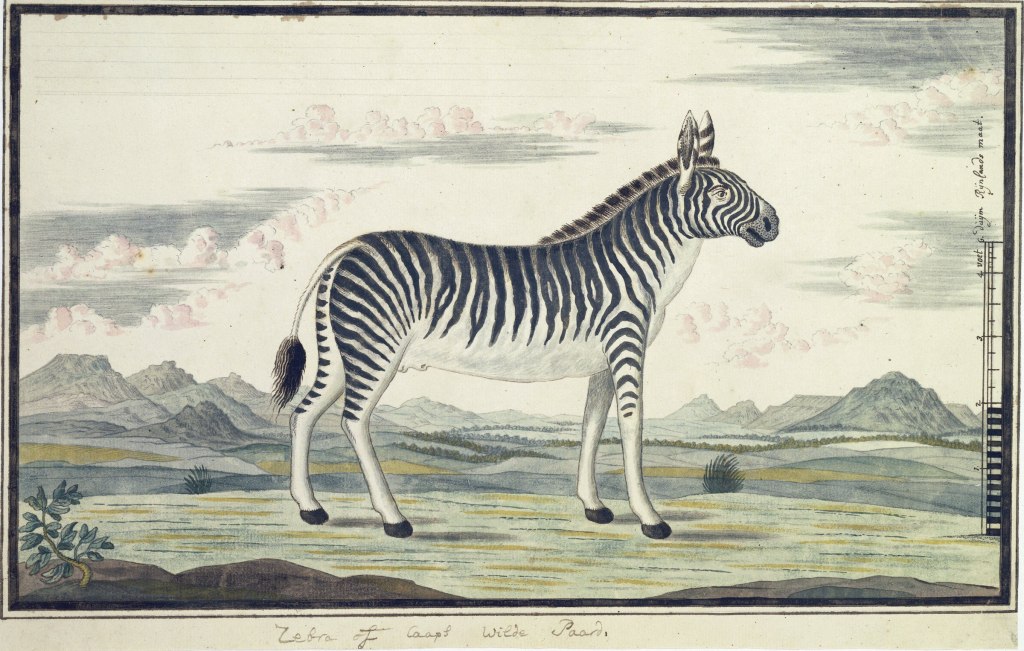

Zebras and Quaggas

In mid-April, two months before he starts his great journey north, he is riding inside the borders of the Cape Colony from Cape Town towards Paarl in the Swartland. He observes the Paardeberg or Horse Mountain which is a 5 to 6 km long series of granite hills in a wide plain that in his time would have been cloaked in fynbos3 and is now a wheat and wine growing region. He tells us that Paardeberg was named after the “wilde paard” (wild horse) which once lived on the mountain.

The Rijksmuseum collection

Burchell explains that the wilde paard is not a horse but a zebra that he suggests should be named “equus montanus”. He describes it as “beautifully” covered with single black and white stripes over every part, even down to its feet, that it lives in mountainous areas and had once inhabited Paardeberg but was now gone.

The animal he describes is the Cape mountain zebra and his proposed name of equus montanus was adopted in 1822 and is still in use.

The Cape mountain zebra was driven into mountainous areas as settlers moved onto the plains; historically it had roamed freely across the grasslands of the Cape but the fact that, by 1810, it was no longer in the area of Paardeberg shows how quickly it was being exterminated.

He goes on to describe two other and very different animals that he points out are often confused with the mountain zebra and with each other.

Smithsonian Institution Library

The first of these is the quagga (he calls it the quakka) which was a sub-species of the plains zebra, he explains that the quagga has brown stripes on its head and the fore-part of its body but has white legs.

In the 18th century herds of quagga roamed the grassy plains of southern Africa but as the settlers moved steadily north from Cape Town they exterminated the quagga partly to harvest their meat and skins and party because they competed for grazing with domesticated sheep and cattle, and not least because, in the words of the sixties rock band Love, “they were on my land”.

Burchell records shooting quagga for meat on many occasions while he is in the area of the mission at Klaarwater but the fact that he doesn’t mention them as he journeys from Cape Town to the Great Karoo suggests that they had already been exterminated in the Cape Colony.

It is believed that the last wild quagga was shot in 1878 and the last captive specimen died in an Amsterdam Zoo in 1883. The zoo only discovered it was extinct when they ordered a replacement.

© Steve Middlehurst

The last of his three descriptions is referred to as the “zebra” which he describes as having double-brown and white stripes on its head and body but with white legs and that it lives on the plains. We now know this as the plains zebra or Burchell’s zebra (Equus quagga burchellii)2. On his journey north he often mentions zebra, sometimes in herds of thirty animals, but sometimes just as skins.

Although Burchell’s zebra is the most common of all the zebras the IUCN Red List still classifies it as “near threatened”. Its range is now just 17 countries and it is in decline in 10 of those.

The Great Journey

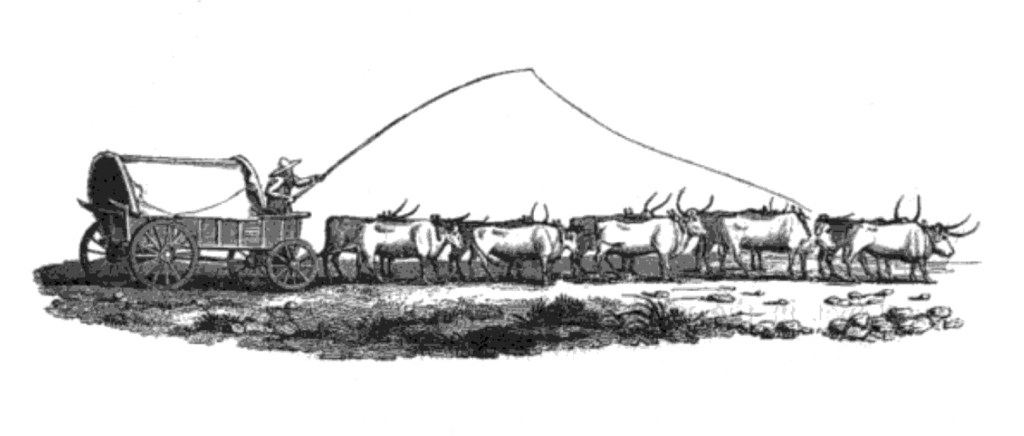

While in Cape Town he recruits two Khoisan1 men, Magers and Jan Kok, who have recently arrived in Cape Town from the mission station at Klaarwater (modern day Griekwastad or Griquatown) and a Khoisan soldier, Philip Willems, whose discharge from the army is arranged by the local commander. Willems is made foreman and the driver of Burchell’s wagon.

Having taken delivery of a wagon he has had built to his own design but along the lines of the Dutch settlers’ ox drawn transport the expedition team pack-up a remarkable list of items, that Burchell calls a “multitude and variety of goods” ranging from trade goods, arms and ammunition, tools, spare parts for the wagon, food, medicines, books and stationary that all fitted into five large chests that would also form the base of his bed. He admits that packing was difficult and that the wagon proved to be overloaded.

Magers and Jan Kok head off to collect the oxen and following a chance meeting in town Philip Willems introduces an old comrade Stoffel Speelman who along with his wife, Hannah, joins the expedition.

On the 18th of June 1811 they inspan the oxen and depart Cape Town.

Hippos

Burchell reaches the mission station at Klaarwater, modern day Griekwastad, on 30th September and bases himself there for four months. He writes to a friend at the Cape that so far he has collected 163 birds, 400 insects, a few small quadrupeds, 1,000 species of plants, some mineralogical specimens and 110 drawings.

He makes several side trips from Klaarwater including a loop to the east to a spot on the Ky Gariep River (now the Vaal) where it joins the “Modder” river (the confluence of the Rietrivier and the Vaal) where some of his party shoot two hippos, he continues north up the Vaal and reports that there were “many” hippo in this area, they shoot two more for food.

First Rhinos

Burchell’s biggest problem by the time he reaches Klaarwater is his lack of men. He had hoped to recruit Khoisan people along the way but with no success. He decides to leave his wagon and ride across country to try to recruit men in Graaff Reynét (Graaff-Reinet), 400 km as the crow flies southeast of Klaarwater and back inside the Cape Colony.

No European had previously made this journey across the territory of the San people who, in 1812, were the only inhabitants of the region. Burchell calculates that he can make the journey in eleven or twelve days but it takes a month to work their way through inhospitable terrain in conditions that range from extreme heat to freezing cold. Burchell is helped along the way by the San whom he respects, admiring their way of life, and describing them as “men of lively manners and understanding”; a feeling that seems to been reciprocated as he is invited to visit their kraals along the way.

A few days after leaving Klaarwater whilst heading south following the Brak River he meets Kaabi, a San Chief whose kraal lies in their direction of travel so they agree to travel together. Five days later they arrive at the kraal and are encouraged to stay for a day or two and join the villagers on a rhino hunt as four have been seen in the vicinity. The hunt is delayed and when it eventually starts Burchell is too busy writing his journal to join them but the news soon comes back that Speelman, who has proven himself an excellent marksman, has shot a rhino. This causes great excitement in the kraal with the villagers “half-crazy with joy ….. old women skipping and dancing …… laughing and clapping their hands.”

Burchell rides twenty odd kilometres to the site of the kill taking several San and the oxen he has been using as pack animals with him. On reaching the hunters he hears fromSpeelman that he has shot a second rhino and he is very keen to describe his technique.

His explanation highlights the fact he is hunting with a single-shot, muzzle loading, flintlock musket so the first and only shot needs to count; the fact that he despatches two rhinos with one musket ball each is testament to his skill and bravery.

The hunter needs to approach downwind to try and get within range of a musket-shot4 but if the rhino sees or otherwise senses the hunter it is impossible to escape so the man must stand still and then, as it charges, “spring suddenly to one side to let it pass”.

This evasive action is designed to give the hunter time to reload before the animal finds him again.

This is Burchell’s first encounter with a rhino and he carefully records his first impressions. The first animal was a male black rhino, Diceros bicornis, and when they butchered it for meat they found more musket balls than they had fired showing that the creature had been previously hunted inside the Cape Colony and had “sought refuge beyond the boundary.”

The San continue to be very excited about the kill and consume a remarkable quantity of meat spending the whole night “broiling, eating and talking.”

© Steve Middlehurst

Having dipped as low at 2,300 wild black rhino numbers have slowly increased due to conservation efforts. There are now around 6,500 in the wild. There were once hundreds of thousands.

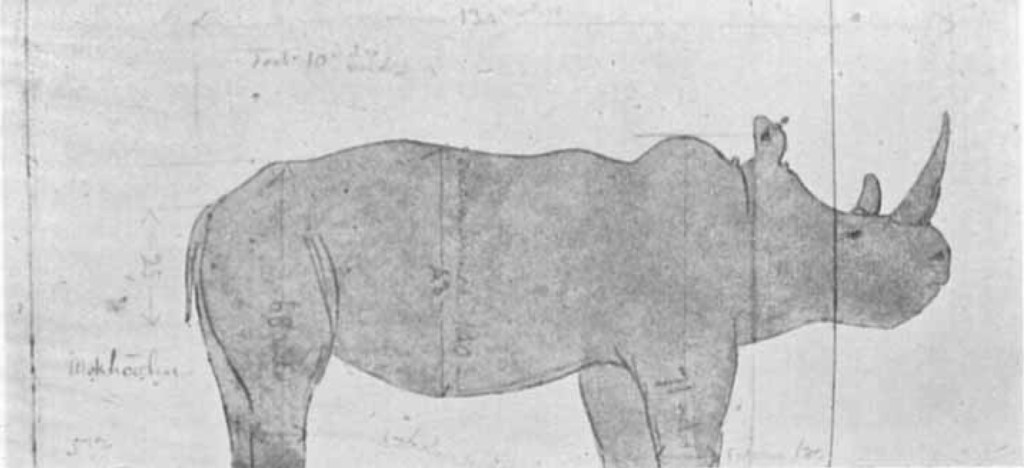

The next morning Burchell proceeds to the second kill, a female, which he measures, sketches and records before the San arrive to butcher it. He says on first view it is like an enormous hog but on closer inspection its “shapeless, clumsy legs and feet” resemble the hippopotamus and the elephant. He goes on to describe the animal in some detail mentioning that because he has run out of ink he has to record his observations in his notebook in the animals own blood.

The most interesting part of his lengthy description concerns the horn which remarkably he quickly recognises and proves to be hair not bone. He observes that at its base the horn is “rough and fibrous like a worn-out brush”. It is a great shame that our inability to universally communicate such a simple fact 220 years after Burchell first recognised it has nearly led to the extinction of this wonderful animal and its cousin the white rhino.

It is worth noting that these two animals and eight other black rhinos his men shot were killed to provide meat. These first two were shared, and probably mostly eaten by the San people from Kaaba’s kraal.

The Anthill Tiger

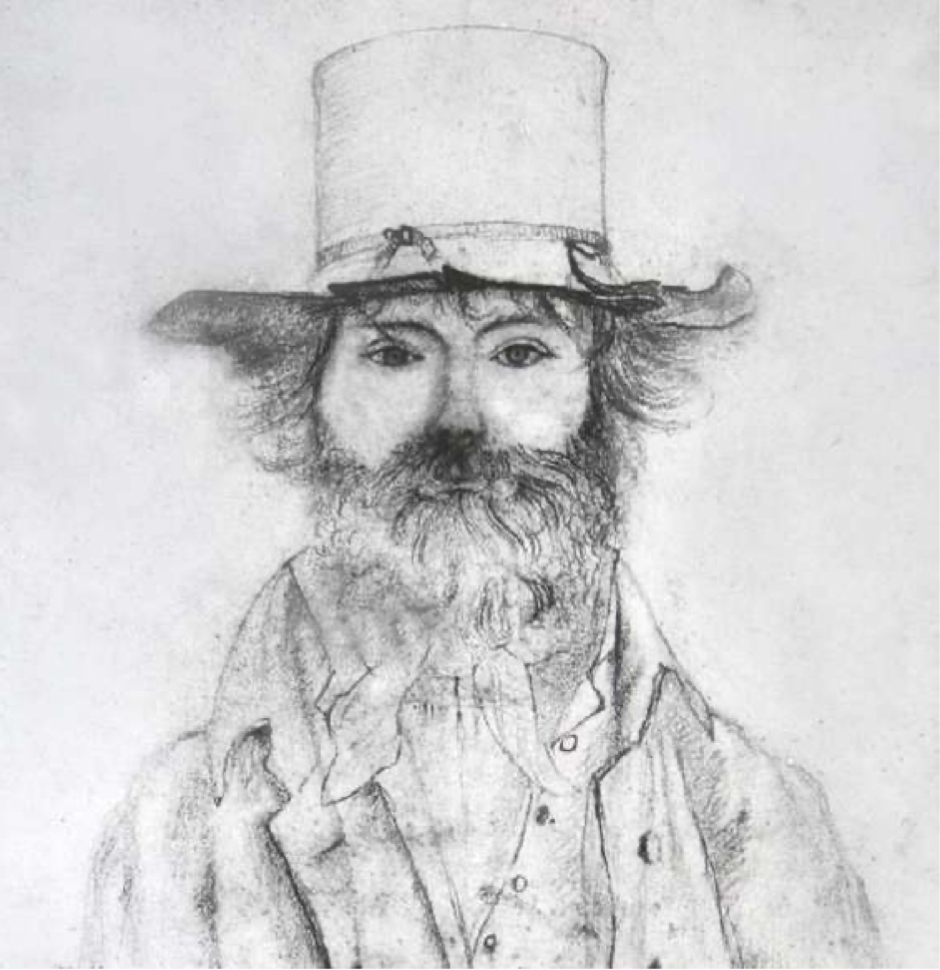

After returning from his recruitment drive in Graaff Reinet Burchell leaves Klaarwater again at 4pm on the 6th June 1812.

As can be seen in his self portrait of around this time he looks a little less fresh faced than when he started.

The next leg of his journey will take him further north than any other European.

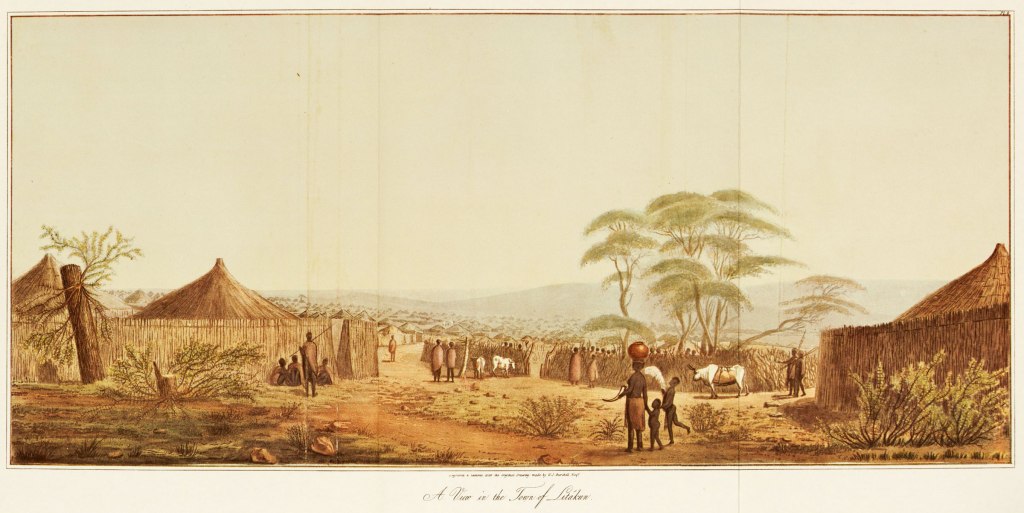

In the middle of July they reach Litakun, near present day Dithakong, which he describes as the chief town of the Bachapins and where he stays for two weeks before looping south again for most of August to replenish their food supplies.

He returns to Litakun on the 9th September where he sees many skins of a small wild cat that had not previously been scientifically described.

The black-footed cat (Felis nitriles) is the smallest wild cat in Africa; it is only found in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa living in areas of short grass, scrub desert and sand plains where it preys on rodents and birds.

They are famously aggressive earning the nickname anthill tiger.

The remaining population size is estimated at < 10,000 mature individuals with a declining trend due to loss of prey base, non-target poisoning, and persecution.

The Greatest Zoological Discovery of his Life

We are now reaching the point where his two volumes of Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa come to an end.5 Much of our knowledge of the next part of his journey comes from his carefully annotated map. On the 29th September he leaves Litakun and follows the Moshowa River north west for a day before turning onto the plains and heading north towards the Kalahari Desert.

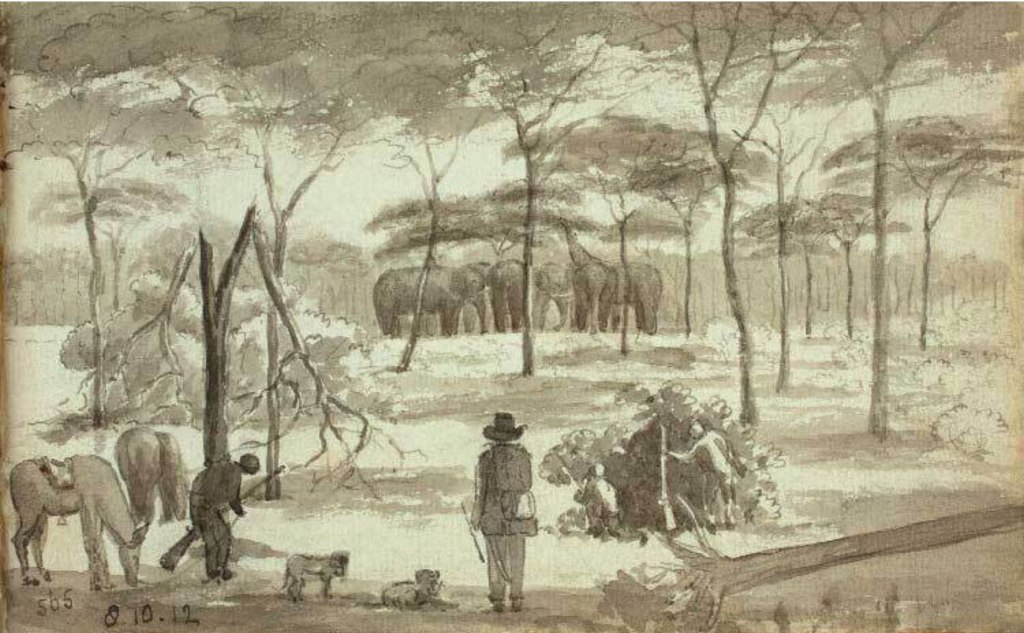

This is dry bush country, the lack of water is evident from the notations on his map; “Last Water Station” and “Desert Station” but on the 3rd October and now 900 km from Cape Town as the crow flies he sees his first Camelopardalis (giraffe) and eight elephants. We know that he was excited by this encounter that generates in him “a strange and peculiar interest at the sight.” Unfortunately any drawings he might have made here have been lost but a little later when he is exploring the mountains north of Chúe he sees six elephants feeding and makes a charming little sketch with himself in the foreground.

On the 3rd October after seeing the giraffe they turn west reaching Chúe Lake and Chúe Spring on the 4th. This is modern day Heuningvlei, a small village once associated with asbestos mining on the edge of the Kalahari Desert and about 60 km from the Botswana border.

Burchell soon heads off to explore the Makuba Range of mountains and on his return to camp on the 16th October he discovers that Speelman has shot another rhino but when he looks more closely at the carcass he realises that this animal is not the doubled horned, black rhino but a species new to science.

©Steve Middlehurst

Having dipped as low as just 30 wild southern white rhinos conservation and anti-poaching efforts have helped the population grow to around 16,000 animals but they are still being poached at a rate of 500 a year in South Africa alone.

He named it Rhinoceros simus and for a time it was known as Burchell’s rhino and is now usually referred to as a white or square-lipped rhino (Ceratotherium simum).6 He described his find to a French zoological society saying he met the white rhino:

” inhabiting immense plains, which are arid most of the year, but every day frequenting the springs not just to drink but to roll in the mud, which, adhering to the hairless skin, forms a protection against the scorching heat of the sun.”

Like his observation of the black rhinos horn being formed of hair not bone I find his recognition that the white rhino rolled in mud to protect it from the sun surprisingly perceptive. He has a remarkable ability to spot important fact based on very limited information.

He goes on to describe the animal in great detail and points out that the Khoisan people had always known there were two species and had given them different names. mokhohu for the white rhino and killenjan for the black rhino

They knew that the white rhino ate grass whilst the black rhino ate trees and bushes which Burchell realises is an observation supported by the different shape of their mouths.

The Natural Philosopher

William John Burchell’s remarkable journey continued for another two and a half years and by the time he returned to Cape Town he had 63,000 specimens and 500 drawings in his trusty wagon. The fact that his published work finishes so abruptly and so far from the end of his journey deprives us from fully understanding how the journey changed Burchell. We know that he arrived in Africa as a botanist and horticulturalist and as an accomplished draftsman and artist but once there he shows, not just an interest, but often expertise in a wide range of natural sciences including zoology, ornithology, astronomy, cartography, geology and anthropology.

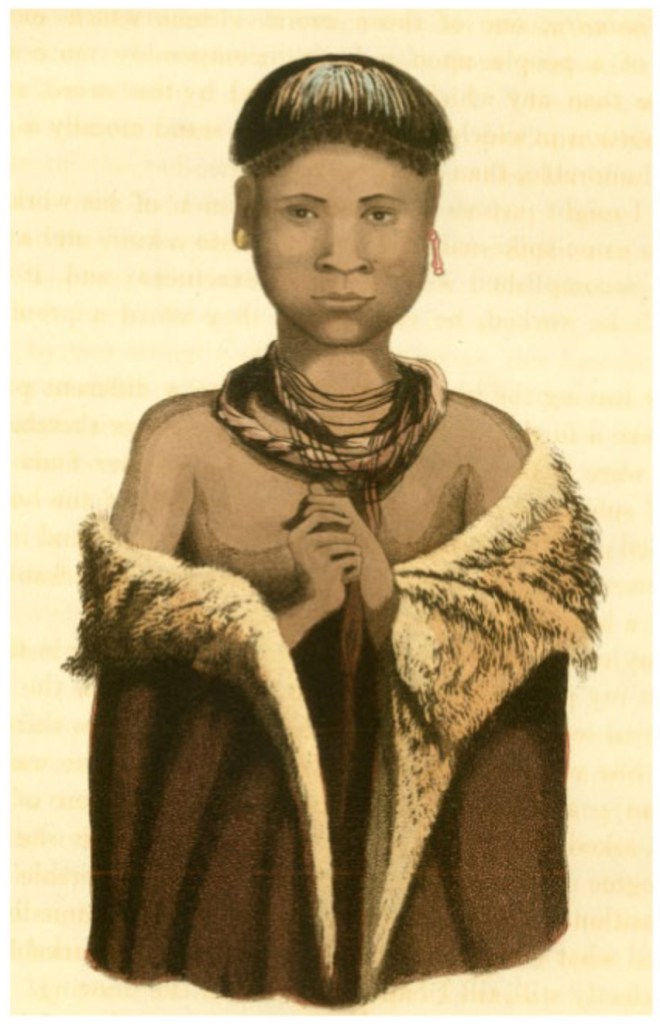

In reading his books it is his empathy with the indigenous people living north of the Cape Colony, in the Great Karoo and up to the edge of the Kalahari Desert that shows his humanity and, in my mind, sets him apart from many of the settlers and missionaries of the time and those that had come before them.

We are quick to lament the near extinction of southern Africa’s large mammals and recognise how the settlers drove them ever further north by hunting, pest control and habitat loss into less and less suitable habitats. We are less ready to recognise that the process of European settlement in southern Africa drove the San and other ethic groups to near extinction in exactly the same way and without doubt destroyed their culture and way of life.7

Burchell, with his normal energy and dedication, starts to study and learn indigenous languages soon after arriving in the Cape and consistently shows respect and understanding of the people he travels with and meets. When he first meets Kaabi, from whose kraal the first rhino hunt departs, they quickly agree to travel together, with Kaabi guaranteeing their safety and Burchell from then on referring to them as “our bushman friends”.

After spending time in the San kraal he describes their approach to life:

“Ambition never disturbs the peace of the Bushman race. And I believe that in this people no existence can be traced of the sordid passion of avarice or the insatiable desire of accumulating property , for the mere gratification of possessing it. Between each other they exercise the virtues of hospitality and generosity ; often in an extraordinary degree.”

Of course, as must be expected of a man of his time, he feels superior to the indigenous people and is patronising in the way he views and describes them but he respects them and their way of life and is critical of the missionaries who are trying to suppress their culture, including their joyful singing and dancing by calling it the work of the devil.

After his great African journey Burchell’s strength, in being the complete natural philosopher, became his weakness as he struggled to write his books quickly enough to catch the public’s interest and was overwhelmed by the task of cataloging his huge collections from St Helena and now South Africa. One senses that this led him to “run away” to Brazil to reprise his first great adventure.

In 1830, in a letter to Sir William Hooker, the first director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew he reveals the mindset that

“I cannot bring my mind to abandon any branch of natural history for the sake of giving more time and attention to any one in particular, although I know this is wrong and can never lead to perfection in any. Still, the contemplation of the whole system of created objects is so fascinating that it is very difficult to turn away from all but a few.”

Final Thoughts

I set out to learn about Burchell’s first meetings with zebras, giraffe, rhinos and elephants and how, for a while at least, two of these iconic creatures were named after him. Like Burchell I have been easily distracted and have, at times struggled to keep on track but I feel in reading his own words and in trying to understand the world he lived in I have come to understand him a little better.

He was a perfectionist with an interest in the minutiae of the whole natural world and this lack of specialisation and his obsessive attention to detail and correctness meant that he never published the learned papers that would have gained him recognition and fame in his lifetime. He remains far better known in South Africa than in his native Britain.

©Steve Middlehurst

He was the first scientist to identify and name many species of plants and brought several back to Britain to be grown in the traditional English garden.

He named, not just the white rhino for the first time but other iconic creatures such as the white-headed vulture, the black-footed cat and the blue wildebeest (see left).

No doubt he will be decolonised at some point, we have already discarded Burchell’s rhinoceros and we will at some point no longer have Burchell’s bustard, Burchell’s coucal, Burchell’s courser, Burchell’s gonolek, Burchell’s sandgrouse or Burchell’s starling in the world of ornithology or Burchell’s zebra, Burchell’s sand lizard and an army ant and a few plants in zoology and botany.

But, that will be a shame as he loved Africa, its people, its animals and its landscapes and his writings give us a wonderful and I suggest unequaled, insight into South Africa at the beginning of the 19th century before the settlers moved north from the Cape Colony and changed everything for ever.

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Footnotes and References

- I have not found any source that sheds light upon the ethnicity of the three men Magers, Jan Kok and Philip Willems whom Burchell employs. He refers to them as “Hottentots”, which is now, quite rightly, recognised as being a racial slur, but in the 19th century was used to refer to the indigenous nomadic pastoralists, the Khoekhoen people of southern Africa. However, San and possibly other nomadic people were living in the Great Karoo in Burchell’s time. I believe that Khoisan (or Khoe-San) is the accepted and non-insulting collective term used to describe the indigenous peoples of southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages. I will therefore use Khoisan to describe the people Burchell meets on his travels.

- When researching the post I wrote about Crawshay’s zebra (Travelogues-Crawshays+Zebra)I spent a lot of time reading about the three different species of zebra (mountain, Crevy’s & plains) and the disputed number of sub-species of the plains zebra. Disputed because naturalists and scientists have changed their minds several times over the years as to what constitutes a species and a sub-species and whether the differences are, in fact, just local variations in stripe patterns.

- Fynbos: the name originates from the old Dutch words for “fine bush” and is the collective name for the plants that naturally occur in the mountains of the Cape region. It is a heathland characterised by low growing shrubby plants such as its 652 species of heather but also proteas, irises, daisies, orchids and citrus. 70% of the plants in this region are unique.

- Brown Bess the British Army standard issue musket used at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, officially called the India Pattern Model, could penetrate 3 x 1″ thick deal planks set 12″ apart at a range of 60 yards. A professional soldier of the era was trained to fire 3 rounds per minute, i.e. once every 20 seconds. Of course Burchell may have been using a different musket but this gives some idea of the range of these weapons.

- Volume 1 was published in 1822, seven years after his great journey finished and volume 2 in 1824. Interest in his adventures had waned and his publisher was allegedly disappointed with sales. The suggestion is that he lost his publisher so no volume 3. To compound the problem only one of his journals survive so his movements from Litakun north and then his two year journey back to the Cape are well recorded on his wonderful map but otherwise poorly documented.

- Wildlife guides will generally tell you that “white” is a corruption of the Afrikaans name “wijd” or wide given to the animal in the 1830s but Kees Rookmaaker of the Rhino Resource Centre is adamant that this is a myth and that it is highly unlikely that anyone in the Cape Colony in the 1830s had ever seen a white rhino given that they lived in remote areas far from the Cape as shown by William Burchell who is 900 km from the Cape before he sees one. Rookmaaker suggests that the colonists called it white because it is the opposite to black. See Kees Rookmaaker 2019 Debunked: the name of the White rhinoceros. Pachydermjournal.org

- There is a myth that southern Africa was practically uninhabited when the first Europeans arrived at the Cape but in truth the region supported a significant population of around 250,000 Khoisan living in the region in small family-based groups. They were decimated by smallpox in the 17th century and those that weren’t pushed north as the colony expanded were mercilessly persecuted in the 18th and 19th centuries. They were exploited as slave labour, systematically hunted as “vermin”. In the district of Graaff-Reinet that Burchell visits twice during his journey 2,500 San were killed and 654 captured in the period of 1786 to 1795 by Dutch East India Company “commandos”.

- William John Burchell 1822 Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa. Vol 1. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Ore & Brown https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=4r8NAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PR2&hl=en

- William John Burchell 1824 Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa. Vol 2. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Ore & Brown https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Travels_in_the_Interior_of_Southern_Afri.html?id=_78NAAAAQAAJ

- Roger Stewart & Marion Whitehead 2022 Burchell’s African Odyssey: Revealing the Return Journey 1812 – 1815. Cape Town: Struik Nature

- Leonard Thompson 2001 A History of South Africa. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/file%20uploads%20/leonard_monteath_thompson_a_history_of_south_afrbook4me.org_.pdf

- Desmond T Cole 1971 William John Burchell’s Lithops https://www.jstor.org/stable/42791285?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Jason Woodcock 2020 Lost Forever Quagga https://naturenook.co.uk/2020/08/12/lost-forever-quagga/

- Professor E.B. Poulton 1905 William John Burchell https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA00382353_10350

- A.J.E. Cave 1961 Burchell’s Original Specimens of Rhinoceros Simus http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/130/1300833513.pdf

- A.J.E. Cave 1947 Burchell’s Rhinicerotine Drawings http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/131/1311733162.pdf

- Elana Begin 2000 Representing the Bushmen: Through the Colonial Lens https://www.jstor.org/stable/40238891

- Fay Anderson and Richard Geary-Cooke. Willian John Burchell. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA00423203_4333

- Roger Stewart and Brian Warner 2012 William John Burchell: The multi-skilled polymath https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0038-23532012000600015

Leave a reply to The Fall and Rise of the Bontebok – Travelogues and Other Memories Cancel reply