Where Did all the Lions Go?

We are all too aware that the demise of wild life in Africa is as a result of human activity and it is well recognised that this started in the colonial era but, naively I had always thought that, apart from the ivory trade, the elimination of Africa wildlife mostly started in the late 19th century with the notorious Scramble for Africa.

My eyes were opened when researching William Burchell’s remarkable journey of 1810 to 18151 from Cape Town to the Kalahari and back via the Eastern Cape; I was struck that the animals I expected him to see are never mentioned or are first encountered nearly 1,000 kilometres from the Cape; and, that many of the iconic African mammals that he does observe are obviously already in serious decline as early as the very beginning of the 19th century.

We know which medium and large mammals were living on the coast of southern Africa during and after the last ice age and, outside of wildlife reserves, just about none of them survive in the Western or Eastern Cape, the area of the old Cape Colony.

This level of localised extinction is not unconnected to universal extinction. The last bluebuck was shot by settlers at the Cape in 1799, the quagga which was once common there was extinct by 1878, the Cape mountain zebra is vulnerable to extinction, the white southern Rhino was within a hair’s breadth of global extinction before the great Ian Player stepped in and the list goes on.

So, when were the seeds of extinction first sown?

The Arrival of Us

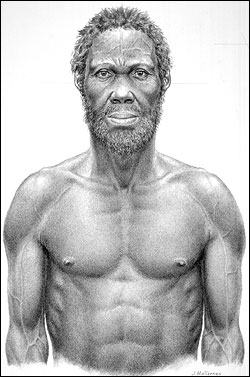

Homo Sapiens, evolved in Africa about 200 ka2 (200,000 years ago), maybe even earlier. No one is quite sure where in Africa this happened as fossil evidence is sparse but most scientists favour East Africa with the earliest remains found so far being in Ethiopia.

As this reconstruction of Homo sapiens idaltu to the left shows, they really were us.

We now know that this new hominin was a wanderer and evidence has been found across Africa as well as in the Middle East and, as far away as China showing they wandered far and wide long before the well recognised out-of-Africa expansions starting 50 to 60 ka to which everyone can trace their DNA. It appears that those early migrants died out.

Around the same time as these first hominins were living in Africa and making those early forays into the wider world there were abrupt and significant changes to the climate as the world entered a protracted ice age. From 195 to 123 ka Africa became cooler and drier, deserts got bigger, forests shrunk and Homo Sapiens, whom from now on we will just call people, found that their Eden was fast becoming a challenging place to live with much of North, East and West Africa becoming inhospitable and probably uninhabitable.

The First Inhabitants of the Cape

©Steve Middlehurst

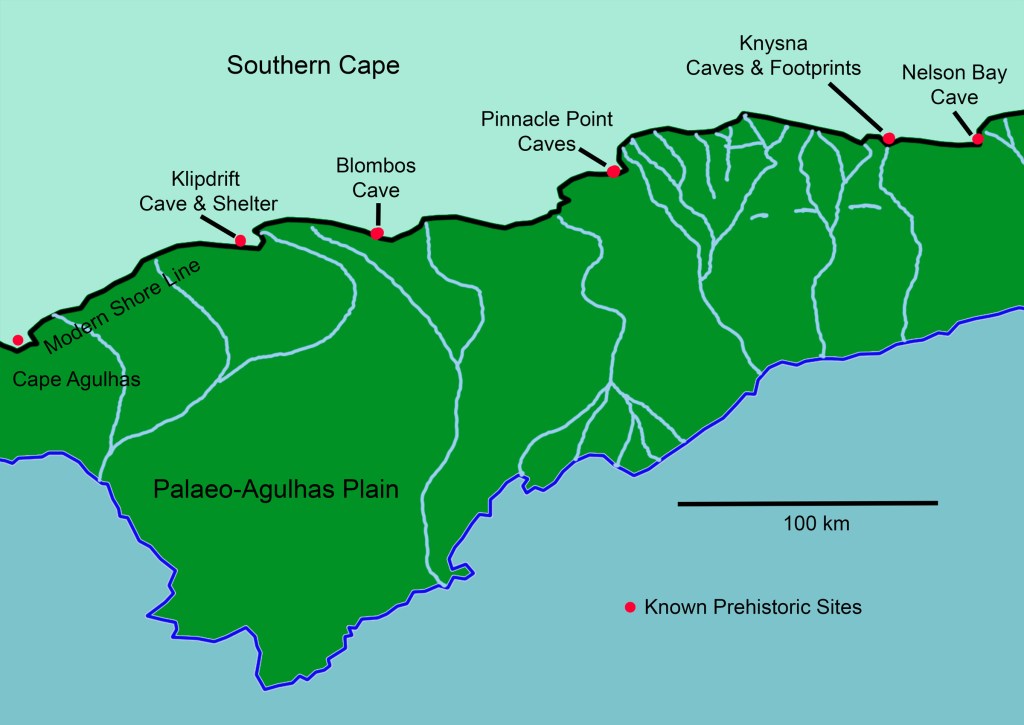

One theory suggests that the people who survived this 70,000 period when most of Africa was uninhabitable did so by moving south ahead of the changing landscape. They arrived on the southern coast of Africa some 164 ka and settled in caves where they and their descendants continued to live for the next 130,000 years. The southern coast was blessed by the warm Agulhas current that brought warmth and ample rainfall in contrast to the cold and dry interior.

Curtis Marean, who developed this theory, and found a number of these caves at Pinnacle Point, near Mossel Bay on the Southern Cape, believes that at its lowest ebb the human race was down to just a few hundred individuals living along this coast and that all humans outside Africa descend from this group.

©Steve Middlehurst

This theory is emotionally compelling not least because we can visit these caves and consider the idea that our ancestors once lived here, cooked food on the hearths, designed and used new tools, created decorative art, developed language, looked out at the sometimes near and sometimes distant ocean, learnt about tides, collected shellfish and, no doubt as they were human, argued about all these things around their fires.

The alternative theory which appears equally compelling is that although this southern group were fundamental in developing new technologies and a culture which, post ice age, spread north again the out-of-Africa migrations of 50 to 60 ka carried the DNA of eastern African rather than southern African survivors.3

Beginning to Change the Wilderness

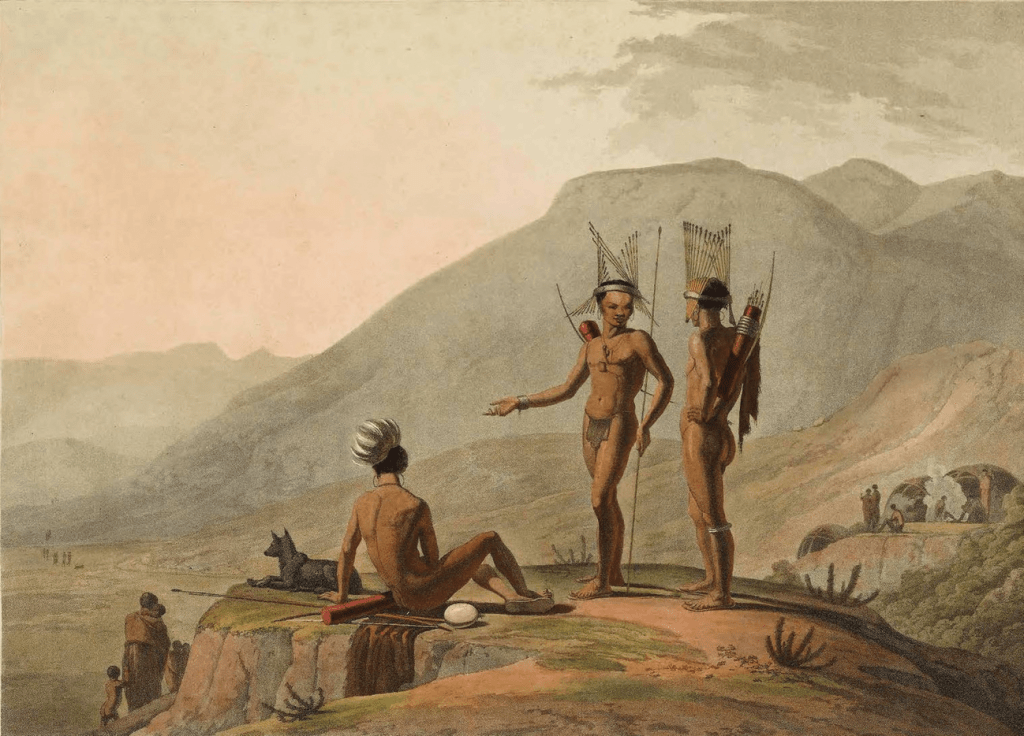

The cave dwellers on the southern coast were the direct ancestors of the hunter-gatherer San people who were still in what is now South Africa when the first Europeans arrived in 1652. Although by then they had been mostly displaced by the Khoikhoi people who had brought their herds of sheep and cattle to the Cape around 2,000 years ago.

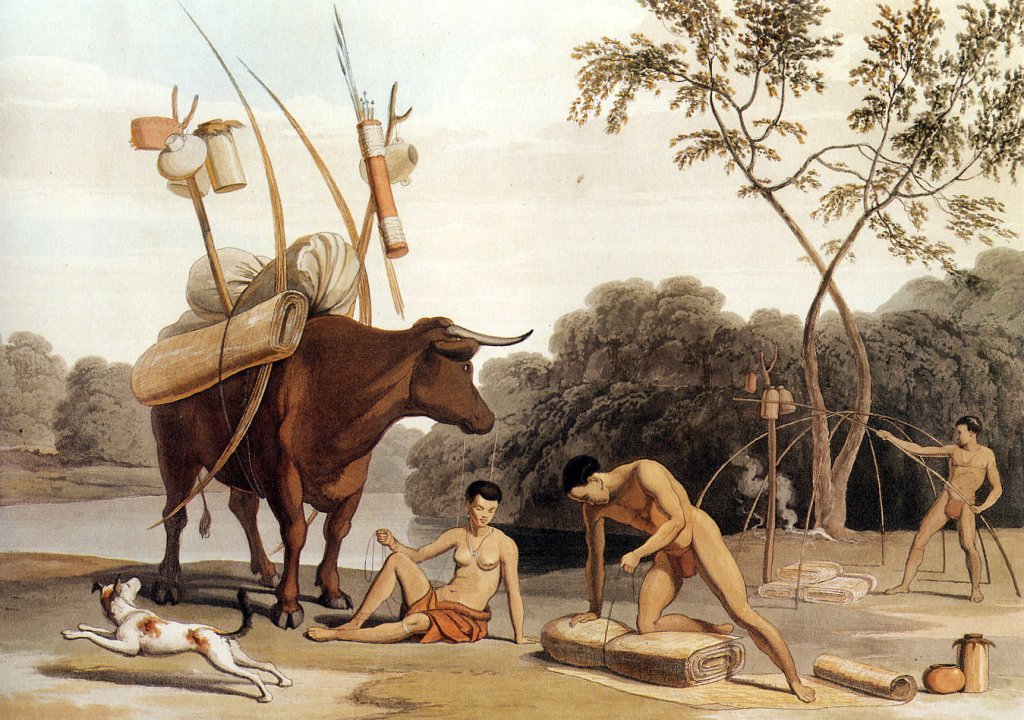

Samuel Daniell 1804

Initially the San’s ancestors’ survival, and indeed success, on the Southern Cape came from exploiting the resources of the ocean and the fynbos landscape. They were the first people to harvest shellfish which is a high-quality source of protein and the omega-3 fatty acids that are essential for brain development; for carbohydrates they turned to the land.

The plants in this region are fire-adapted; many create a dry woody mat of old and dead growth below their greenery which ensures that when a spark lands or lighting strikes the fynbos burns easily and rapidly. This clears the land and lays down fertiliser in the form of ash. Some plants release their seeds after the fire has passed, some need fire to crack open their seed cases, some re-shoot from burnt stumps and some have stored energy and water in underground bulbs or tubers known as geophytes from which a new plant develops.

The simple invention of a weighted digging stick, as shown to the left, enabled the San to harvest these geophytes to provide a vital source of carbohydrates.

The small number of San living along this coast would have had an intimate knowledge of their hinterland and there is evidence that they were using fire, on a small scale, to encourage bulb production.

The San lived in this way on the Southern Cape for tens of thousands of years.

They neither made a significant impact on the environment nor on the abundant wildlife that lived, not just in the fynbos, but on the San’s third natural resource: the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain.

The Palaeo-Agulhas Plain

The cyclical ice ages that took turns to hold Africa in a cold and arid state locked up vast amounts of water, not just at the poles but over a large part of North America and Northern Europe and in glaciers on mountains across the globe. Sea levels fell and coast lines moved away from the continents.

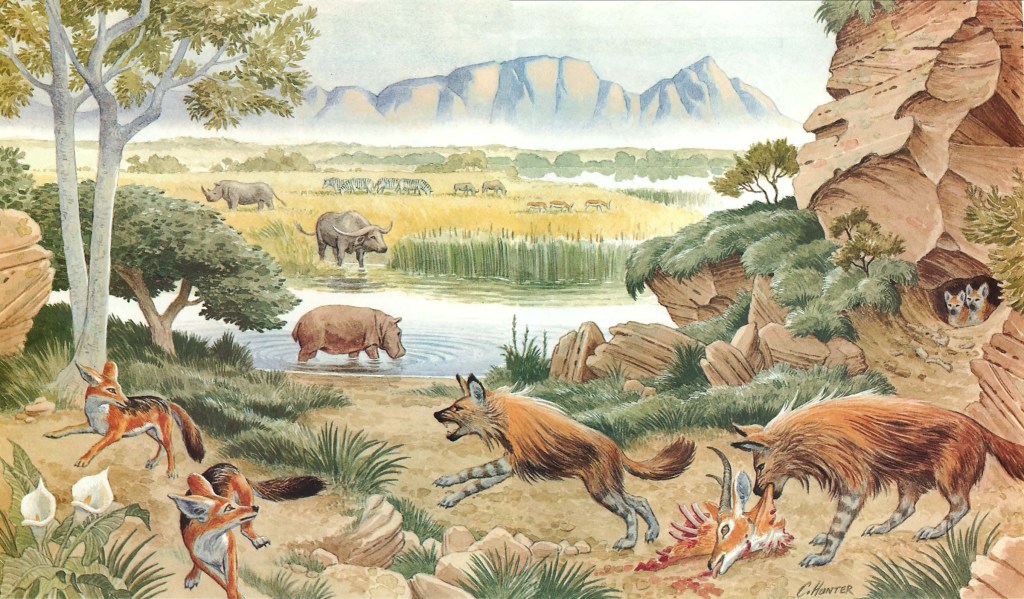

After C.W.Marean and Others

The low sea levels created a vast lowland, the size of Ireland, extending out from the southern coast of Africa: the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain, nourished by the warm Agulhas current, was probably as close to the mythical Eden as humans have even known.

Painting by C.Hunter

This, now submerged, ecosystem boasted heavily wooded rivers and streams, abundant nutritious grasslands and savanna-like floodplains. It was teeming with wildlife similar, in terms of wildlife diversity and density to the modern day Serengeti.

The nature of cyclical ice ages mean that sea levels rise and fall over lengthy 50,000 to 70,000 year cycles as the polar ice caps grow and contract so the size of the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain (PAP) changed dramatically from warm periods where the coast would be where it is today and cold periods where it retreated 100 km south.

During the warm periods, such as our current era, when the PAP shrank and then disappeared, animals were forced to move from its abundant grass and woodlands onto the modern mainland where the fynbos offered nutrient-poor and unpalatable vegetation and where they would have been trapped between the coast and the Cape Fold mountains with the dry regions beyond them.

Most mammals adapted so that, at worst, small populations, so-called refugee species, survived in this comparatively narrow belt of land during the warm periods and then recolonised the PAP as it re-emerged in the next ice age.

About 14,000 years ago around the beginning of the current warm period a small number of mammals did become extinct: the giant cape zebra, the giant wildebeest, the giant long-horned buffalo and the southern springbok. It is probable, but not certain, that this was due to the loss of the PAP, their preferred environment and an inability to adapt to less nutritious grasslands.

Those are probably the last four large mammals in southern Africa to become extinct as a result of habitat loss that was not caused by humans.

The First Herders

The Khoikhoi people who were semi-nomadic herders arrived on the Southern Cape some 2,000 years ago bringing their herds of cattle and sheep. These herds needed both grazing and water and the Khoikhoi learnt to use fire to clear the fynbos and promote the growth of grasses.

When Vasco da Gama passed the Cape in 1495 he named it tierra del fume, the Land of Smoke, after seeing billowing smoke from fires inland. This was quite possibly the Khoikhoi’s clearance fires.

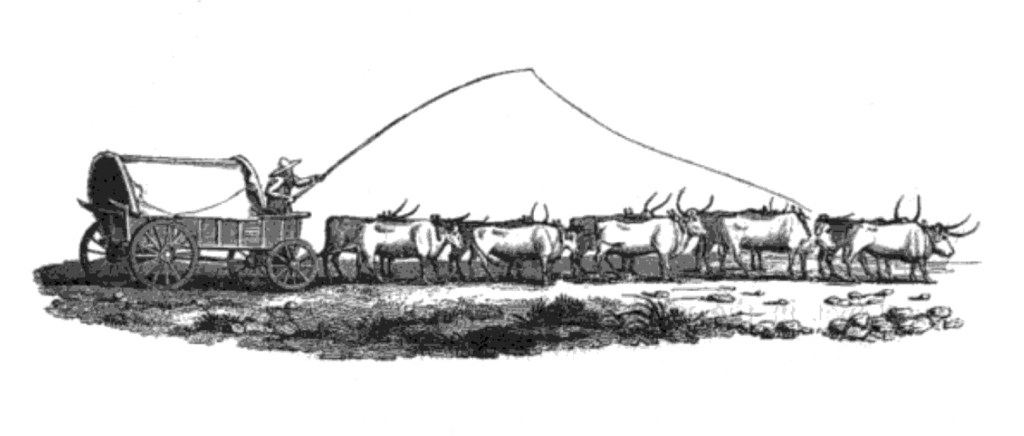

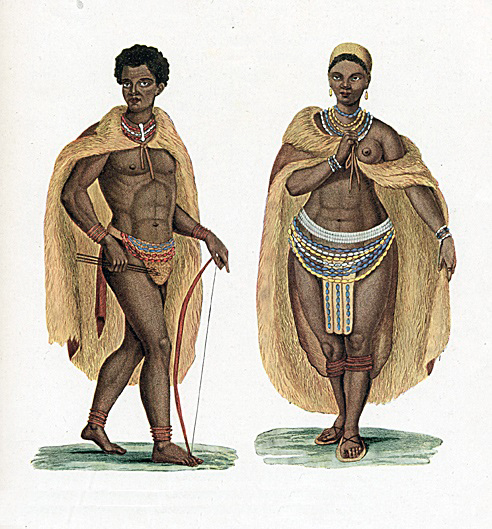

Samuel Daniell 1805

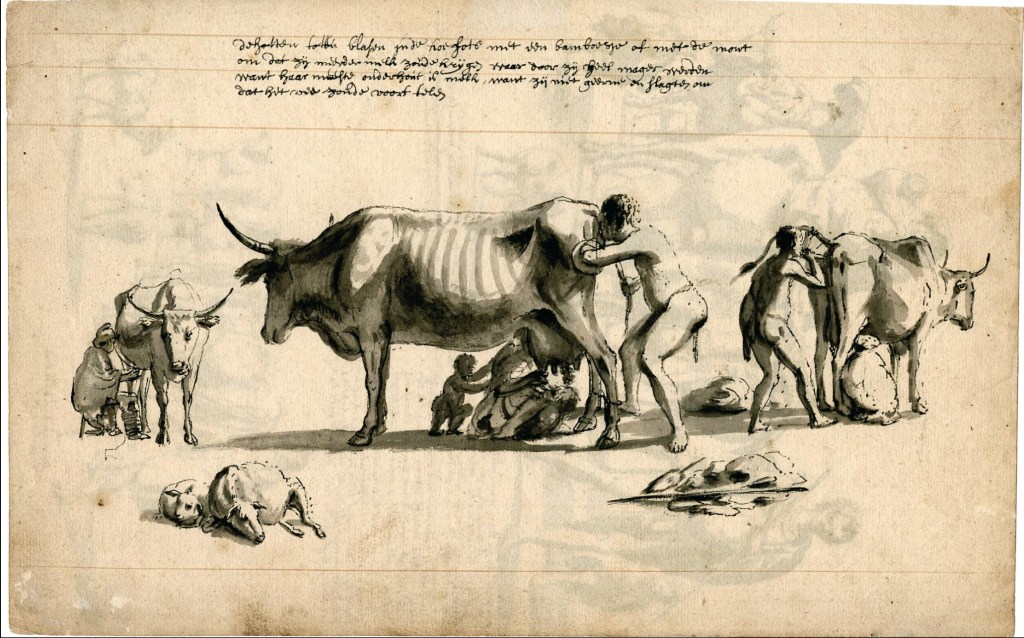

Conflict arose between the Khoikhoi and the San who were competing for resources that required diametrically opposed approaches to land management. The Khoikhoi herds were large, settlers arriving in 1652 describe herds of 20,000 sheep and cattle, which grazed out new grass in a matter of weeks forcing the herders to move and clear more fynbos with fire.

By 1652 there were around 50,000 Khoikhoi living in the southwestern Cape so we might argue that, whilst they were manipulating the environment by burning the fynbos to create grazing the impact on the ecosystem was still limited.

However, the Khoikhoi’s cattle were dairy herds which meant each family needed large numbers of cattle to provide an adequate supply of food. It is estimated that a family group of eight people needed 40 lactating cows, plus one or two bulls as well as calves to sustain the herd and sheep for meat. Simple mathematics suggests that 50,000 people could easily have had 500,000 domesticated animals.

From an environmental perspective the vegetation, and thereby insects, small lizards and small mammals, would have been significantly impacted by domesticated ungulates rather than the wild grazers who had evolved coextensively with the fynbos over tens of thousands of years.

The San, who had retained their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, were now under significant pressure from the pastoralists who were not only clearing the fynbos which provided their carbohydrates, but were depleting their sources of protein by killing or evicting wild ungulates who were competing for the limited grazing.

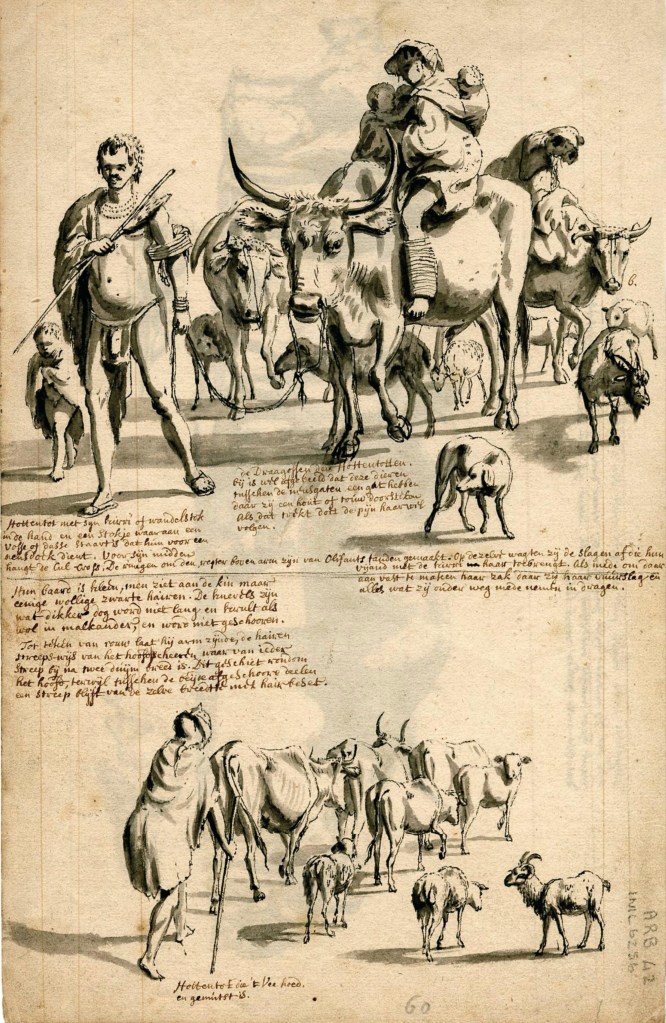

Library of Congress

As wildlife populations diminished the San began to steal Khoikhoi sheep and cattle as a source of protein which in turn brought the two groups into direct conflict. One study argues that it would have taken very few thefts to initiate “widespread warfare” and the San would have increasingly retreated into more remote areas.

By the time the first Dutch settlers landed on the Cape the San were nearly invisible having retreated far inland to an area historically referred to as Bushmanland which is an arid area south of the Orange River, west of Kenhardt and east of Springbok in the Northern Cape around 500 km north of Cape Town. An area where William Burchell interacted with the San in 1811.

So, by the time the settlers arrived, the Khoikhoi had already fundamentally altered the ecosystem of the southern Cape, large areas of fynbos had been converted to poor grassland, the original human inhabitants had been evicted and the mammal population had been reduced.

The seeds of extinction had already been sown well before 1652 but the Khoikhoi’s impact paled into insignificance when compared to what came next.

The Seaway to the East

From the 17th century European navigators and sea-born traders were drawn to China and India like moths to a lamp. Since Roman times spices and silk had been sought after luxury items among the European elite but in the 17th century the land routes to India and China were controlled by the Ottoman Empire. Bartolomeu Dias rounding, what he called, the Cape of Storms in 1487 was a significant event as in 1498 and by following Dias’ route Vasco da Gama reached India. For the next 100 years Portugal dominated the so-called Cape Route to India and beyond.

The Portuguese made an attempt in 1503 and then again in 1510 to establish a trading post at the Cape but the Khoikhoi chased them back to their ships on both occasions and they seemingly lost interest as they already had a provisioning port at St Helena and then later at trading ports established in Mozambique. They were presumably still anchoring in Table Bay to refill their fresh water barrels as they named the area Rio Duce or Sweet River.

In 1600 a number of Khoikhoi people broke away from their semi-nomadic lifestyle and established the Camissa settlement.

It stood near where the Cape Town waterfront is today, and the Khoikhoi began to trade fresh produce with the passing mariners.

The Empty Land

In 1652 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) appointed Jan van Riebeeck to lead an expedition to establish a provisioning station at the cape of Good Hope. He arrived with five ships and ninety followers on the 6th April and followed his orders to built a small fort, protect sources of fresh water and lay out a small garden to grow vegetables.

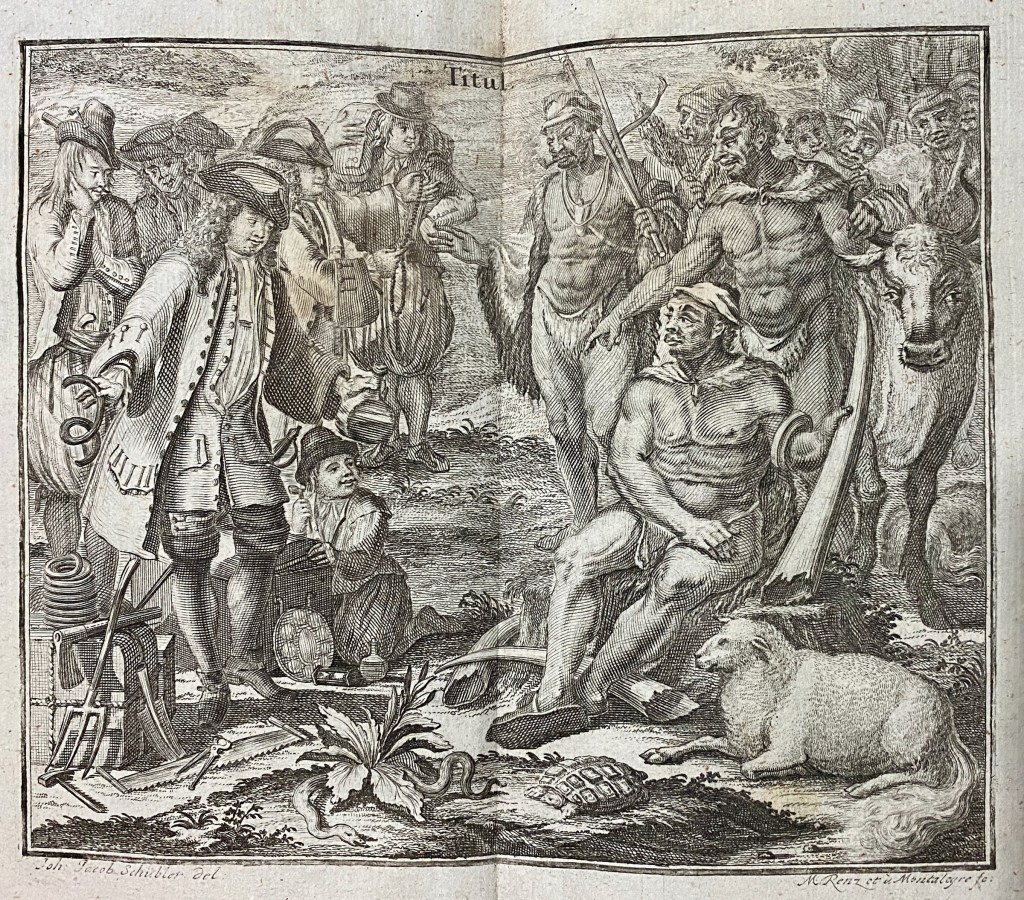

Painting by Charles Davidson Bell

Initially the intent was to maintain a small operation that could also trade for meat with the Khoikhoi and then provision the VOC’s ships en-route to Java in the East Indies. This policy was gradually eroded and finally discarded.

The seated Khoikhoi holds an ivory tusk which the European appears to be attempting to trade for alcohol, in his left hand and tobacco in his right.

The small, contained provisioning station grew into a settlement and the settlement expanded to become a colony encompassing the well watered and fertile land around modern day Stellenbosch and then even further to find grazing for the settlers’ sheep and cattle. The Khoikhoi found themselves prevented from grazing their cattle on the best land and violence soon erupted.

They traded away some of their cattle to the Dutch but lost far more to seizure by the government of the Cape as reparations for war and through theft by the European freemen who had been awarded land. In the early 18th century as the colony spread further the majority of the remaining Khoikhoi were dispossessed of the last of their pastures, their access to water and ultimately their herds. Three times in the early 18th century smallpox epidemics swept through the colony having a dramatic impact on the previously unexposed Khoikhoi and the remaining San in the region.

Khoikhoi living on the fringes of the colony took to cattle raiding and quickly became labelled as vermin that could and should be exterminated. White farmers, especially on the north-eastern frontier, took to raiding Khoikhoi settlements outside of the colony, killing the menfolk and carrying off women and children into slavery.

Europeans saw the land as empty, populated by near-naked savages who knew no god that a European could recognise, who built no proper towns, did not understand how to conduct commerce and had developed no useful technologies.

Cape Town Museum

The Khoikhoi had no farming skills and weren’t domesticated so they held little value as employees or servants. But, beyond the argument that they were uncivilised and of no economic value the first settlers saw the indigenous people as sub-human, variously describing the Khoikhoi as “dull, stupid, and odorous,” as “stinking dogs” and as “the reverse of human kind.”

The pro-slavery faction in Britain at the end of the 18th century employed the same tactics; by dehumanising the black African they excluded them from all societal, legal or religious protection. As they were not human they could be owned and traded as commodities like any beast of burden. Following identical logic, if a black African is not human they cannot own land, so appropriating African land was perfectly acceptable, no humans lived there.

The demise of the San and the Khoikhoi suited the then popular, official and politically expedient European view of the southern Cape and ultimately of all of sub-Saharan Africa. The empty-land myth was ultimately convenient and self-serving.

It was to van Riebeeck’s and the VOC’s advantage to depict southern Africa as an empty land and to justify the murder and displacement of its indigenous people as mere pest control.

But, it was not just the humans who were in the way of progress.

The Early Settlement and the Environment

The Dutch were dismayed by the abundant wildlife they found at the Cape. To them it was a hostile and dangerous environment that needed to be tamed. There were a significant number of lions in the immediate vicinity of the original provisioning post and van Riebeeck himself comments on a dog being taken by a lion from inside a house.

In 1656 a bounty was placed on all large carnivores and they were systematically exterminated in the whole Table Bay area.

Their view of wildlife depended on the nature and habits of the animal in question but generally animals fell into one or more categories of dangerous, edible, good sport or vermin. In each case the settlers set out to exterminate them.

By 1700, just 44 years after their arrival, the settlers had exterminated every single animal weighing over 50 kg within 200 km of Cape Town.

To put this in perspective, according to Google Maps it would take nearly 3 hours to drive from Cape Town to Lambert’s Bay or Matjiesfontein and nearer 4 to get to Witsand which is just past the De Hoop Nature Reserve in the east or Wupperthal to the north.

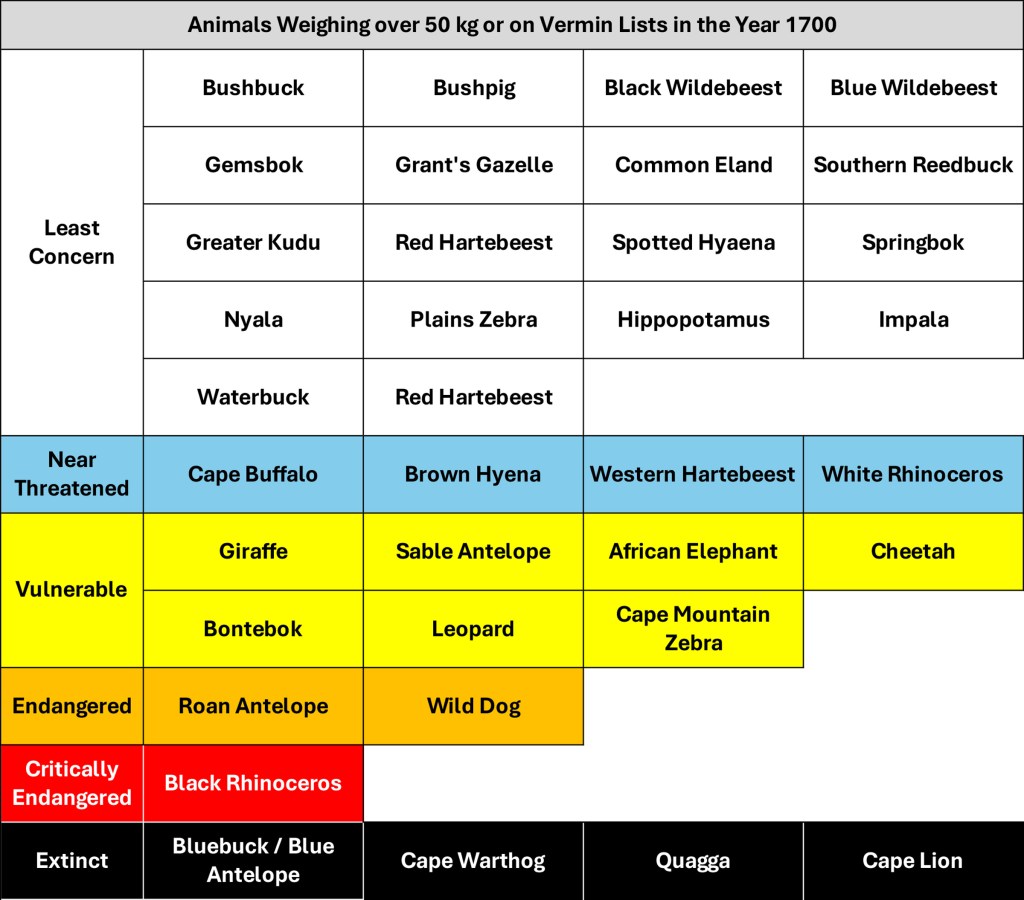

And to further contextualise their disturbing achievement the following table shows the animals known to be have been in this area at the beginning of the colonial age that are over 50 kg; I have included wild dogs as they were hunted as vermin. 36 mammals of which half are now either extinct or in danger of extinction according to the IUCN,

We now understand at least some of the interdependencies that exist in a healthy ecosystem so the demise of all the apex predators would have, for example, had a significant knock-on effect on vultures who remain extinct in the Western Cape other than a small population in the De Hoop nature reserve.

By 1700 the myth of an empty land had come true. Some Khoikhoi lingered in the settlement as labourers but most of the wild mammals had gone.

The impact of the early settlers extended far beyond the borders of the Cape of Good Hope Colony. Settlers were actively encouraged to hunt elephants as a way of supplementing their income and as the settlement spread east the Europeans cleared the elephants in their path. One hunter, Jacob’s Botha, boasted that he was often shooting five elephants a day and on two occasions had killed twenty-two in a single day’s hunting. By 1760 there were no elephants within 800 km of Cape Town.

The Cape Colony

After a short-lived, false start in 1795 the British took possession of the Cape of Good Hope Colony in 1806 an it became known as the Cape Colony. The colony in 1806 had an area just short of 200,000 km2, a population of 60,000 people of whom 27,000 were Europeans, 17,000 Khoikhoi and 16,000 slaves.

Over time Britain despatched more immigrants and the colony grew, merino sheep gradually became the small-stock animal of choice and by the middle of the century there were around 20 million sheep on the grasslands and in the Karoo.5

William Burchell

I started this post by expressing my surprise regarding the distance Burchell travelled from Cape Town before he met Africa’s most iconic animals and that many mammals you might have expected him to have seen are absent from his journals. I accept that this is an anecdotal and unscientific form of measurement but he is famous for the accuracy and diligence of his record keeping so we can, at least, accept his journals as educated observations.

Burchell explores the Colony for several months before leaving its borders and heading north. During that time he rarely if ever mentions large mammals and when he does mention the Cape mountain zebra at Paardeberg it is to say that “at the present day, not one is to be found there”.

It is not until he leaves the borders of the colony that he begins to see large mammals; but, he is 300 km from Cape Town in the Roggeveld when they find and shoot “several” quagga for food. At the Brakke River, around 400 km from Cape Town his Khoikhoi hunters wound a lion and near Klaarwater, modern day Griekwastad, around 650km from Cape Town, he sees first hippopotamus, the tracks of a lion and notes that plains zebra and hartebeest are in the area.

He subsequently travels south east initially following the Orange River and eventually down to Graaf-Reinet.

It on this journey when staying with Kaabi, a San Chieftain, that he sees and draws his first black rhinoceros. He is still far outside the colony and in the area that the San settled when driven from the Cape by the Khoikhoi.

©Steve Middlehurst

After his return from Graaf-Reinet he travels north from Klaarwater to Litakun and Heuningvlei, 900 km from Cape Town and it is there that he sees giraffe and elephants for the first time and makes the greatest zoological discovery of his life when his Khoikhoi companion shoots a rhinoceros that has not previously been described by a European. We now know it as a white or wide-lipped rhinoceros but when it was first named it was known as Burchell’s rhinoceros.

His return journey takes him from the edge of the Kalahari to the Great Fish River where it flows into the Indian Ocean and along, what we now know as the Garden Route, and back to Cape Town. His published journals finish when he is still in the north but Roger Stewart and Marion Whitehead have pieced together the missing three years of his great journey in a wonderful and entertaining book.8

©Steve Middlehurst

Much of this part of his great journey is back inside the boundaries of the Colony so knowing that the Dutch settlers had eliminated the carnivores and all animals heavier than 50 kg a hundred years earlier it comes as no surprise that his mammal sightings continue to be few and far between.

He shoots an eland, sees a blesbok and describes a blue wildebeest; and arriving in the Eastern Cape he sees an oribi, a type of duiker. As he follows the coast back to the Cape collecting hundreds of botanical specimens he shoots a leopard near Knysna and sees Cape buffalo near George; it is possible that buffalo and elephant were in the Mossel Bay area as he finds and describes dung beetles and finally at Swellendam he spots a bontebok.

Final Thoughts

Three distinct groups of people had in turn dominated the southern coast of Africa by the end of the 18th century; the San, the Khoikhoi and the Europeans.

The San were hunter-gathers who survived there for 170,000 years and in that time had little or no adverse impact on the environment.

Library of Congress

They were displaced 2,000 years ago by the Khoikhoi who were semi-nomadic pastoralists and who created grazing for their herds of sheep and cattle by burning large areas of the natural vegetation. Wild herbivores competed with the domesticated herds so their local numbers were no doubt depleted from hunting and the pressure to move further from human settlement.

But, if the seeds of extinction were first sown by the early pastoralists the Europeans arrived and sowed far, far more.

When the Dutch arrived there was still enough wildlife in the immediate vicinity of Table Bay to horrify them and for the next 150 years they remorselessly hunted down and killed every animal weighing more than 50 kg in a radius of 200 km from Cape Town.

©Steve Middlehurst

By the time William Burchell walked from Cape Town to the Kalahari and back via the Eastern Cape all medium and large mammals were just about locally extinct. He is hundreds of kilometres from Cape Town before he sees rhino, zebra or elephants and his journals for the whole of his 7,000 km journey record sightings of animals in tiny groups or alone. He sees one bontebok, eight elephants, five zebra, one (dead) white rhino and so on and so on.

In just 150 years Europeans destroyed the ecosystem of the Western and Eastern Cape pushing the survivors far out to marginal habitats in the north and northeast. In the following decades the colony expanded to fill all of southern Africa and the view that wildlife was either dangerous, food, vermin or good sport prevailed but that’s another story.

©Steve Middlehurst

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Footnotes and References

- See my previous post about William Burchell’s great journey at https://travelogues.uk/2024/04/24/three-zebras-and-a-rhino/

- ka means kilo annum, a thousand years, so 100 ka means something happened 100,000 year ago.

- The alternative theory, based on studies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is that a small number of people left their southern caves and spread up the eastern seaboard around 70 ka joining other pockets of survivors in eastern Africa. The arrival of these small groups possibly brought the technologies, culture and ideas that had developed in the south including painting, and new ways to make tools. This small group of southern migrants were subsumed over time by a much larger number of eastern survivors and whilst their arrival with new ideas and new technologies may have been a trigger for the earliest out-of-Africa migrations but the maternal lineage of all humans outside Africa derives from an eastern African population with any southern African ancestry significantly diluted.4

- Teresa Rito and others. 2019 A dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6426877/

- European breeds of sheep had been introduced by the Dutch which were cross bred with the Khoikhoi’s sheep to produce a “good mutton sheep with coarse wool”. However in 1789 fine-wool bearing Merino sheep arrived and thrived in the climate of the cape. By the middle of the 19th century there were around 20 million sheep on the grasslands of the colony and in the Karoo and the importance of small-stock farming in supporting an export economy meant that wildlife which had been already severely depleted under the previous regime was scheduled for extermination by the new government.

- William J Burchell 1822 Travels in the Interior of Africa Vol. I https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=4r8NAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PR2&hl=en

- William J Burchell 1824 Travels in the Interior of Africa Vol. II https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=_78NAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PP8&hl=en

- Roger Stewart & Marion Whitehead 2022 Burchell’s African Odyssey: Revealing the Return Journey 1812 – 1815. Cape Town: Struik Nature

- Curtis W. Marean 2010 Pinnacle Point Cave 13B (Western Cape Province, South Africa) in context: The Cape Floral kingdom, shellfish, and modern human origins http://in-africa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Marean-2010-JHE-pinnacle-point-flora-shellfish-and-modern-human-origins.pdf

- John W. Wilson & Richard B. Primack Extinction is Forever https://books.openedition.org/obp/10432?lang=en#:~:text=Nevertheless%2C%20Africa’s%20wildlife%20did%20not,the%20elephant%20relatives%20(Proboscidae)%2C

- Shannon L. Carto, and Others. 2009 Out of Africa and into an ice age: on the role of global climate change in the late Pleistocene migration of early modern humans out of Africa https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047248408001863

- Popular Archaeology 2016 Where Hominins Became Human https://popular-archaeology.com/article/where-hominins-became-human/

- Pippin M.L. Anderson and Patrick J. O’Farrell 2012 An Ecological View of the History of the City of Cape Town http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269089

- Sumner La Croix 2018 The Khoikhoi Population: A Review of Evidence and Two Estimates https://www.aehnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/AEHN-WP-39.pdf

- John Wright San History and Non-San Historians https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/8766683.pdf

- Andrew B. Smith 1986 Competition, Conflict and Clientship: Khoi and San Relationships in the Western Cape https://www.jstor.org/stable/3858144?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Mick D’Alton 2023 Our Changing Agulhas Plain: Life and Extinction https://nuwejaars.com/our-changing-agulhas-plain-life-and-extinction/

- Jan A. Venter and Others 2019 Large mammals of the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain showed resilience to extreme climate change but vulnerability to modern human impacts https://nuwejaars.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2019-VENTER-et-al-Quarternary-Science-Reports.pdf

- Lt. C.M. Meyer 1988 From Spices to Oil: Sea Power and the Sea Routes Around the Cape https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.ajol.info/index.php/smsajms/article/view/143245/132991&ved=2ahUKEwjVgd_a6fiFAxXDZkEAHS9qDQoQFnoECAwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3leoefyLMp3GMHnjdsS1ci

- Camissa Museum. the Camissa Settlement https://camissamuseum.co.za/index.php/orientation/meaning-of-camissa

- Shaw Badenhorst, and Others 2016 Large Mammal Remains from the 100 ka Middle Stone Sage layers of Blombos Cave, South Africa https://www.jstor.org/stable/24894826?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- South African National Parks. Table Mountain National Park https://www.sanparks.org/parks/table-mountain/explore/fauna-flora/mammals

- Dimple Lephaila 2020 Shining a Light on Fynbos Wildlife https://www.wwf.org.za/our_news/our_blog/shining_a_light_on_the_fynbos_wildlife/#:~:text=It%20may%20be%20hard%20to,environmental%20factors%20squeezed%20them%20out.

- Dominic Chadbon 2019 Fynbos and Fire: Why Does it Burn? https://thefynbosguy.com/fynbos-and-fire-why-does-it-burn/

- Lloyd Rossouw The Extinct Giant Long-Horned Buffalo of Africa https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA10162275_576

- Judith Sealy and Others 2020 Climate and ecology of the palaeo-Agulhas Plain from stable carbon and oxygen isotopes in bovid tooth enamel from Nelson Bay Cave, South Africa https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/271861

- Kyle D. Kauffman and Sumner J. La Croix 2005 Company Colonies, Property Rights, and the Extent of Settlement: A Case Study of Dutch South Africa, 1652-1795 https://escholarship.org/content/qt2q0704w6/qt2q0704w6_noSplash_08eea96ecde8666a80d0e252871e358e.pdf?t=krndfc#:~:text=Over%20the%20next%20143%20years,than%20of%20the%20Dutch%20government.

- Roger B. Beck 1998 Review of “The Cape Herders: A History of the Khoikhoi of Southern Africa by Emile Boonzaier, Candy Malherbe, Andy Smith, Penny Berens” https://www.jstor.org/stable/221155

- Susie Newton-King Background to the Khoikhoi Rebellion of 1799 – 1803 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/8766712.pdf

- Lance van Sitter 1998 “Keeping the Enemy at Bay”: The Extermination of Wild Carnivora in the Cape Colony, 1889-1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3985183?read-now=1&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents

- Rhodes University 2013 Bring Back the Springbok https://www.ru.ac.za/perspective/2013archive/bringbackthespringboks.html#:~:text=Until%20120%20years%20ago%20the,landscape%20in%20search%20of%20food.

- Pippa Skotnes 2022 People Were Once Springboks https://tswalu.com/people-were-once-springboks/

- Richard G.Klein 1986 The Brown Hyenas of the Cape Flats https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234046254_The_brown_hyenas_of_the_Cape_Flats

- Keith Somerville (2016) Ivory: Power and Poaching in Africa. London: C. Hurst & Co (Publishers) Ltd.

Leave a reply to The Fall and Rise of the Bontebok – Travelogues and Other Memories Cancel reply