- First Contact

- Forming Strategies to Stop the Slave Trade

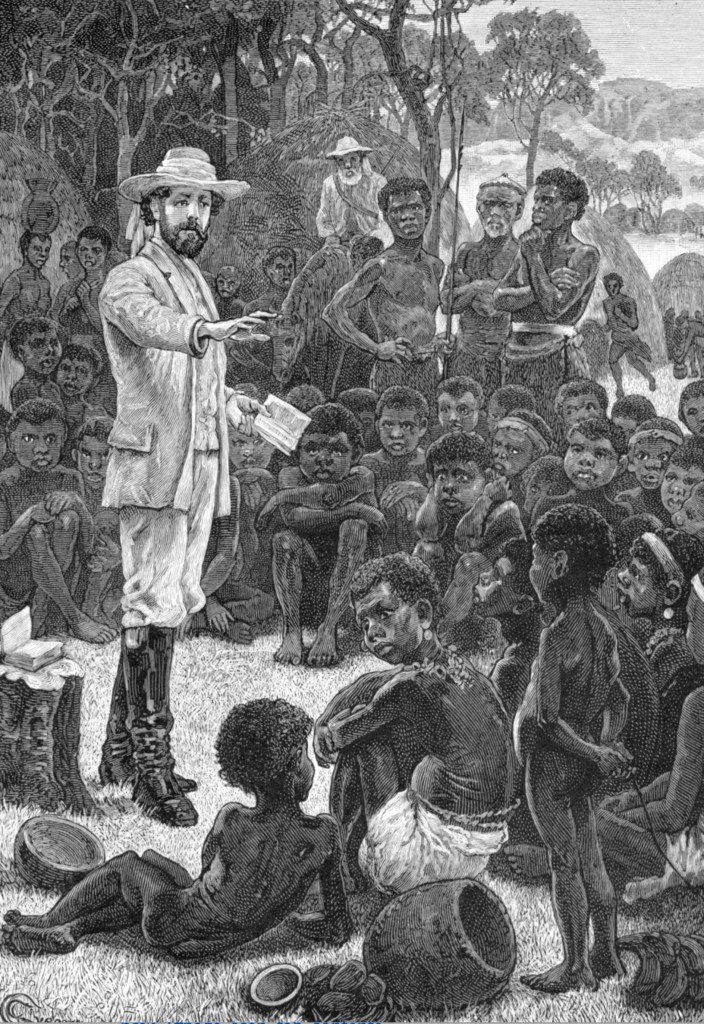

- The Bishop’s Congregation

- July 22nd 1861 – First Armed Conflict

- The Militant Bishop and the Second Battle

- The Battle of Sasi Hill, Zomba 14th August 1861

- The Aftermath

- Retreat

- The Consequences

- Footnotes and References

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, New Haven: Yale University Press 2010

The slave trade in Africa was buyer driven. It was complex and fragmented trade but generally the Europeans took enslaved people from the west coast and from south of the Zambezi River in the east while the trade on the rest of the east coast responded to demand from Arab countries and for workers on plantations on islands in the Indian Ocean including Zanzibar and as far afield as India and Ceylon.

There was also a significant trans-Saharan trade through Timbuktu to Morocco which was still active as late as 1922 and a trade through the Nile Valley that primarily took women and girls from the Sudan and Ethiopia and that the British endeavoured to suppress in the 1870s and 80s.

The west coast trade was eventually stopped because, in the nineteenth century European countries passed anti-slave trade and or anti-slavery laws1. After 1807 the British transformed themselves from the leading buyer and transporter of West African slaves to become an anti-slavery police-force running down and capturing 1,600 slaving ships and freeing 150,000 slaves2.

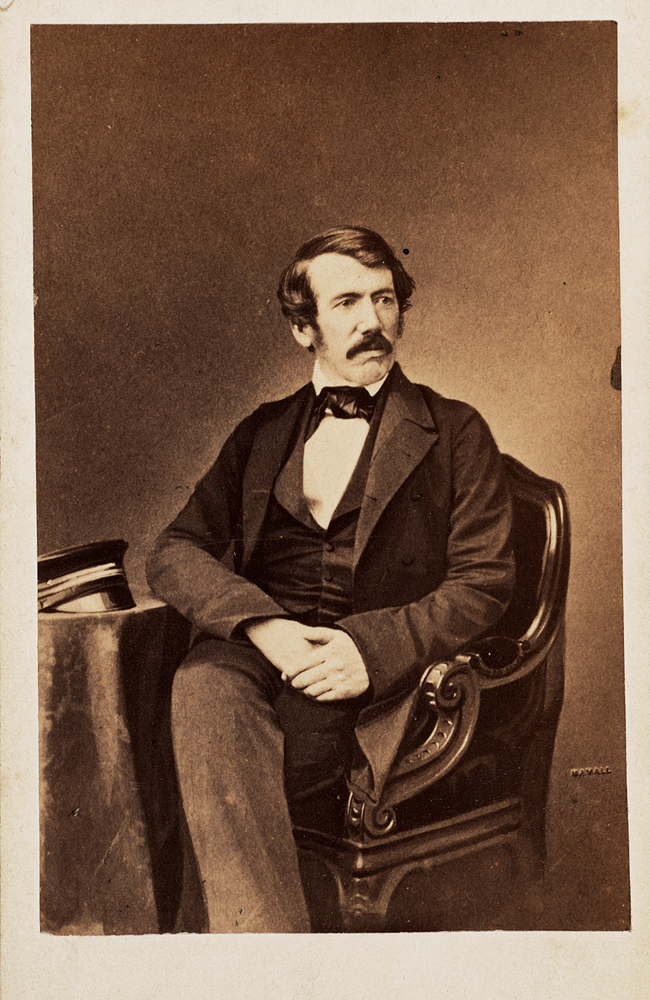

This about-face was powered by the flames of public opinion, flames that were fanned from the pulpit and kept alight by men such as Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce and David Livingstone.

The Bishop of Oxford in November 1859 captured the public mood:

“England can never be clear from the guilt of her long continued slave trade till Africa is free, civilised and Christian”

At the end of the 18th century The Enlightenment3, calling for reason to achieve knowledge, freedom and happiness for humanity, had become a major influence on educated society, religion and politics. These new ideas combined with other more pragmatic considerations4 and the realisation that a slave based economy was unsustainable in the long-term; slaves made up 80% of the population of the West Indian colonies and there had already been uprisings in places such as Haiti.

On the east coast there was an element of political suppression with the British Government forcing the Sultan of Zanzibar into closing the long established slave market5 there in 1873 and subsequently forcing him to prohibit slavery in his domains in 18976.

This was an important step towards ending the east coast slave trade as it severely disrupted the market. Christopher Rigby, Her Majesty’s Consul in 1860 and 61 estimated that 25,000 slaves were being transported each year to Persia and the Arab states and “many others to Reunion for the French and to Cuba for the Spaniards”7.

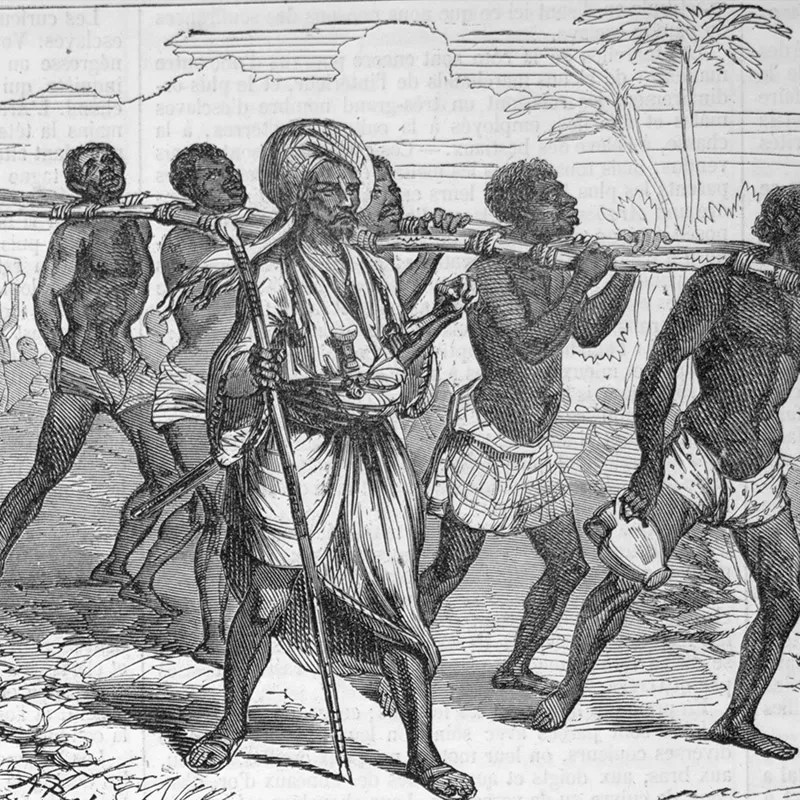

Engraving by Edwin Stocqueler

However, the east coast trade survived these moves, and it was force of arms or the threat of force that finally shut-down the last of the major traders. Some of this force was at the instigation of the British government such as the short-lived patrols by the Royal Navy in the Mozambique Channel8 and the more successful Cape Squadron in the 1860s.

Like so many actions in the days of colonisation and Empire, suppression inside what is now Malawi grew from seeds planted by an adventurer, in this case Livingstone, was nurtured by religious missionaries, escalated into physical force by commercial interests and concluded by government-endorsed military action.

Tens of thousands of people were caught up in this story but only a tiny minority left any written records and nearly all of these were written by the British missionaries, traders, senior soldiers and colonial administrators who were involved. The notorious Tippu Tip is the only east coast trader whose memories are recorded, and he was never in Malawi; we hear nothing but some distant whispers from the freed slaves, the villagers and the colonial troops who played an active part.

This is the story of the first attempt to suppress the slave trade by force; it is the story of Doctor Livingstone and Bishop Mackenzie and the Magomero mission 1861 to 1862..

First Contact

In September 1859 David Livingstone reached what is now Lake Malawi which he named Lake Nyasa. A local chief, Mosauka, invited the expedition party to camp under a great banyan tree which can still be seen today inside Liwonde National Park. A large Arab9 slaving party was camped nearby and in time the leaders of that party came over to meet them and to try and sell some children. On discovering the explorers were English the slavers promptly left, broke camp and disappeared during the night10.

In his journal Livingstone says less about this caravan than we might expect; he tells us:

“They had been up to Cazembe’s Country 11 the past year, and were on their way back, with plenty of slaves, ivory, and malachite 12 ….. They were armed with long muskets, and, to our mind, were a villanous-looking lot.”

He explains that his camp near the southern end of the lake was one of the great slave trade routes passing through the lake area from the interior and that there was a steady trade of ivory, slaves, malachite and copper ornaments between Cazembe and Katanga’s country and Kilwa on the Swahili coast and with the Portuguese in the South.

Livingstone wrote that Colonel Rigby at Zanzibar13 believed that nearly all the slaves sold in Zanzibar came through the “Nyassa District”.

Over the course of the 19th century the Lake became a major hub for the slave trade with multiple routes connecting the Luangwa Valley and the Congo Basin to the Swahili ports on the Indian Ocean and the Portuguese on the Zambezi River.

Slaves might have walked over 2,000 kilometres to reach the lake and still had another 600 left to reach the coast.

Forming Strategies to Stop the Slave Trade

Livingstone uses the experience of meeting this slave caravan to expound upon his theory for suppressing the trade, a theory that he says “all the intelligent (British) officers on the coast agree with.

He argues that if the British based a small steamer on the lake and purchased all the ivory on offer then the salve trade would no longer be profitable. John and Fred Muir, who founded the African Lakes Company, twenty years later, had the same idea, or Livingstone’s idea still had credibility.

We can look back now, with the benefit of hindsight, and wonder why this idea became fashionable and how it survived for so long. Livingstone appears to recognise the connection between the ivory trade and the slave trade but he must have believed that they could be delinked.

However, as E.D.Moore14, the ex-ivory trader, argued so strongly, it was the ivory trade that drove the slave trade in East Africa. Once the elephants on the coastal strip had been hunted to extinction the ivory traders or their agents were forced deeper inland to buy ivory; given the prohibitive economic and logistical practicalities of bringing porters from the coast to the interior the only way to transport the ivory was to buy slaves. The chiefs selling ivory soon learnt to have both available and when the traders became better armed and more militant, they raided the interior enslaving fit, strong men and women to carry the ivory they hunted or stole.15

As the African Lakes Company were to find when they started buying ivory in the 1880s, the traders arrived at their depots with the slaves who had carried in the ivory and remained camped there until they had been paid; they then returned to the Luangwa Valley or the Congo Basin to find more ivory. It is unclear whether they took the same slave-porters back to the interior and it is more likely they were sold to traders such as Mlozi or Jumbe who had bases on the lake where they collected together slave caravans before passing them on to the coast.

It is less than obvious how the policy of buying a product that required slaves to transport it was ever going to delink the two trades and stop the slave trade..

The Bishop’s Congregation

In July 1861 Livingstone was back but this time he was guiding the first Scottish Mission, the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) under the leadership of Bishop Charles Mackenzie.

Mackenzie had been consecrated in Cape Town as the first Bishop of Central Africa. He was 36 years old.

The Bishop, with his bishop’s crozier in one hand and a loaded rifle16 in the other, strode into Malawi followed by porters carrying trade goods looking for a site to build his mission station based on Livingstone’s advice. Their journey from the mouth of the Zambezi to the Shire Highlands had been gruelling and instead of the quiet agricultural communities Livingstone had told them to expect they found fortified villages and armed villagers who treated them with suspicion.

They learnt that the villages of the local population, the Mang’anja17 were being regularly raided by the Yao People18 who had moved into the area at the south of the lake in the 1830s and that the “slave-trade was going on briskly.”

On July 16th, as they worked they way towards the Shire Highlands, the expedition stopped at Chief Mbame’s village which is where the Blantyre Mission Church, St Michael and all Angels stands today.19

Mbame tells them that a slave caravan will soon pass through the area on its way south to the Portuguese settlement at Tete20 in modern day Mozambique.

Livingstone says he discussed with his colleagues whether to intervene taking into account that some of their baggage had been left in Tete and might be confiscated in retaliation.

He argues that there are now slavers where they had not been before and that they had arrived here by following in the footsteps of “our discoveries.”

“We resolved to run all risks, and put a stop, if possible, to the slave-trade.“

“A few minutes after Mbamé had spoken to us, the slave party, a long line of manacled men, women, and children, came wending their way round the hill and into the valley… The black drivers, armed with muskets, and bedecked with various articles of finery, marched jauntily in the front, middle, and rear of the line; some of them blowing exultant notes out of long tin horns. They seemed to feel that they were doing a very noble thing, and might proudly march with an air of triumph.”

Livingstone’s account is typically self-serving, particularly the suggestion that the decision to interfere was somehow democratic. Only four Europeans were at Mbame’s when the slave caravan appeared; Livingstone, who was too ill to continue up the road and was resting in a hut; the other three were: his brother Charles, Dr. John Kirk21 and Horace Waller22. Waller wrote an account of the event in his journal that differs from Livingstone’s and provides a little more detail.

“I went to see the Dr who was lying down in his hut and found he had heard the report also. I could see he had a great mind to interfere although it would of course involve most serious interests.”

Wood engraving by J.W. Whymper after J.B. Zwecker

Waller goes on to describe how the slavers appeared uneasy at the sight of the Europeans and seemed intent on passing straight through the village. However, Livingstone in his blue coat stood in their way and put his hand on the shoulder of the leader whom he recognised as the servant of “a worthy in Tete”. This appears to have been enough and Waller says the slavers snatched up their guns and bolted.

Both Waller and Livingstone describe the process of cutting the cords that restrain the females and sawing off the 6 foot long forked “slave-sticks” that shackled the men. (see right)

They now have 84 freed slaves, some of the slavers’ guns and a collection of trade goods including beads and hoes on their hands.

Waller offers a touching description of how the newly freed slaves react:

“They crouched down in a closely packed group and witnessed what was going on. One by one they seemed to get a glimpse of its import and then, slowly at first, but in its own unmistakable way, rose the measured sound of thankfulness. None who have not heard a multitude clapping the hands together in time hollowed in the palm to make a low deep sound – and at what is called slow time in marching – can understand the effect it produces. Slowly it rose, louder and louder till its solemn sound told gratitude was coming to hearts whose hope was well night dead in its long long sickness.”23

As previously mentioned we rely heavily on European witnesses throughout this era but very occasionally they record what has been told to them by Africans.

Livingstone writes that one little boy said:

“The others tied and starved us, you cut the ropes and tell us to eat; what sort of people are you?—Where did you come from?”

Waller passes on that some of the “liberated slaves” told them:

“Three of the drove had had their throats cut on the route, they being an encumbrance to the march from their weakness. One poor women unable to carry her child, had it taken away and its brains were dashed out on the spot. Two refractory ones were shot we were told also, this served as a warning to the rest.”

There is a pleasing end to Waller’s account. He says they told the freed slaves to gather up the thongs and slave-sticks that had held them and to make a fire upon which they could cook their evening meal.:

“We had the satisfaction of hearing the laugh so long unheard amongst them as they cooked their night’s meal by the blazing poles.”

Livingstone’s decision to intervene was probably the first direct action taken on land by any European to inhibit the slave trade in the Lake Malawi region and possibly all of East Africa.24

It was to put in train a series of events that would, not only decide the success or failure of the UMCA mission, but would alter the political map of the Shire Highlands and the the Shire Valley and all the area that is now Malawi.

Livingstone tells us that when the Bishop rejoined the party, he had been bathing in a steam below the village, he heartedly approved of the action and enthusiastically adopted the freed slaves to start the mission’s congregation. Until this point, despite having purchased and started carrying a rifle, Mackenzie had been firmly against using force to dissuade the slavers, however, the events of 16th July seemed to have dramatically changed his mind:

“I am clear that in such case it is right to use force, and even fire if necessary to rescue captives. I should do so myself if necessary.”

No doubt the expedition with the Bishop’s new flock of eighty-four freed slaves in tow was in good spirits when it set off the next day towards Soche’s village which lay on the edge of what is now Blantyre.

Mackenzie wrote that during this short journey they came across another six slaves, three women and three boys and again the slavers ran away and the newly freed slaves joined the expedition. Livingstone writes that a other slavers and their captors were at Soche’s but fled before the expedition arrived. He sends Dr Kirk and four of “his” Kololo after them but they are unsuccessful.

Livingstone then tells us:

“Fifty more slaves were freed next day in another village; and, the whole party being stark-naked, cloth enough was left to clothe them, better probably than they had ever been clothed before.”

The frequency with which they meet or hear of slave caravans suggests that large numbers of slaves were on the move throughout the region at any one time. The expedition’s experience was of one slave-trade route that ran down the Shire Valley to Tete yet we know, even south of the lake, that there were at least two other routes.

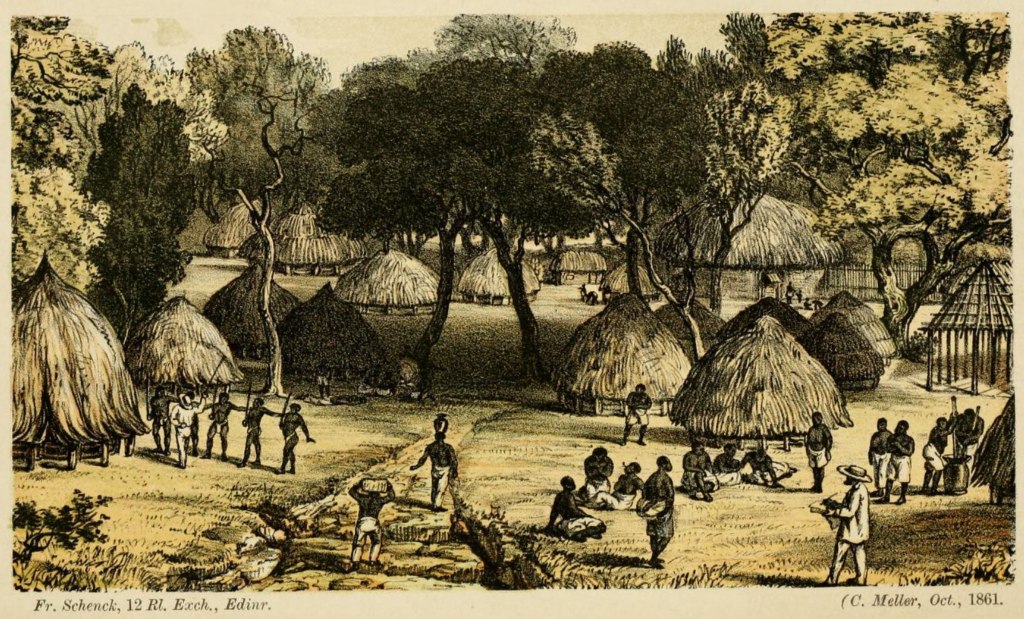

Showing the approximate location of the villages mentioned in the text

Leaving all the freed slaves at Soche’s most of the original expedition continued on in their search for a mission site. Horace Waller and Charles Livingstone scouted ahead and entered Mbona’s village near Chiradzulu Mountain which they ransacked finding another six slaves.

Soon after they reached Chigunda’s where Livingstone had hoped to see Chibaba who had been “the most manly and generous Manganja chief we had met with on our previous journey”. But, Chibaba was dead and Chigunda was now the chief. On hearing that the Bishop was looking for a mission site Chigunda invited them to stay and offered an area in a bend of the river that was called Magomero.

It was pointed out that the mission already comprised a large number of people who would need land for their gardens but Chigunda, who was frightened of the Yao who had already raided and razed many Mang’anja villages in the area, saw the mission with their men and weapons as much needed protection. He assured them there was room for everyone.

There is no mention in Livingstone’s record or Mackenzie’s letters of the expedition leaders or Mackenzie himself going through any kind of assessment process or even discussing whether Magomero was the best location. Livingstone says the Bishop was swayed by Chigunda’s “hearty and spontaneous invitation”. As ever Livingstone shifts the blame for, what proves to be a bad decision, onto someone else. Colin Baker, writing in 1960 says:

“The question of precisely where to place the station was one which, because of his superior knowledge of Africa, was left to Livingstone, “the only man who was in a position to say what was the best thing to be done”.”

Even the Dean of Ely. Harvey Goodwin, who knew MacKenzie personally and became his biographer, questions why he chose this site. There was a good supply of water but the later over-population of the peninsula led to pollution and an outbreak of dysentery that killed fifty of the Bishop’s congregation over the summer of 1861/2. The only other advantage appears to be the bend in the river that enabled them to build a stockade across the open end and use the river as their defence on the other three sides. However, the river was shallow at the best of times and offered little protection.

Instead of selecting a site in the highlands, such as at Soche’s which Baker says both Dr Kirk and Mackenzie preferred, where malaria was less prevalent and where they were only 50 kilometres “from the head of navigation on the Shire”, they were basing themselves in the lowlands where the disease was at its worst. They would be at least seventy kilometres from the Shire River at Walker’s Ferry which, being above the Murchison Cataracts25, only offered navigation north to the lake as opposed to south to the Zambezi River and from there to the Indian Ocean. Even today Magomero is isolated, it is around forty kilometres to Zomba and fifty kilometres to Blantyre.

Henry Rowley who had been left with the boat and only came up to Magomero at the end of July, he expressed his disappointment in his memoirs:

“Magomero was not a large village: nor was it so pleasantly situated as Soche’s or Mongazi’s. It was in a hole in the plain; approach it from what quarter you would, you must descend to it. I felt much disappointed when I saw it; for, in a sanitary point of view, it seemed the worst place that could have been chosen. It was enforced upon the Bishop by Dr. Livingstone …..”

Livingstone had suggested this site long before they arrived here so, for all his African experience, he appeared to believe the presence of Chibaba, a friendly chief who had anyway died before they got there, more important than any other consideration. Landeg White makes the point that Livingstone was a political innocent:

“He was a reliable and often acute observer of people, plants, animals and geographical features. But as an interpreter of local structures of power he was reliable only in the sense that he was usually wrong.”

His reputation was based mostly on his first book and his lectures in Britain; he was a master of self promotion with an uncanny ability to deflect blame onto any convenient companion. For Mackenzie, the mission staff and his newly acquired congregation this was a disastrous combination. The renowned expert gave the Bishop poor advice, quickly dissociated himself from any decisions that went wrong and disappeared as quickly as he could to get on with his misguided mission to find the source of the River Rovuma to prove that he had been right about a navigable route from the Indian Ocean to Lake Malawi.

Their next move continued to dig them into a deeper hole.

July 22nd 1861 – First Armed Conflict

Goodwin, Mackenzie’s biographer, who had access to Mackenzie’s letters and diaries, suggests that their mindset was one of being in the lands of the Mang’anja whilst the lands of Yao were “at a distance”. The Yao raids in the area south of the Chikala Hills were, in their view, anomalies and could be stopped by showing a “firm front”; the Yao would then retreat back to their settlements further north.

Livingstone writes that a decision was made to “seek an interview with these scourges of the country” i.e. with the Yao. So, on Monday 22nd July 1861, they set off towards Zomba and found themselves marching through streams of refugees that were running away from burning villages.

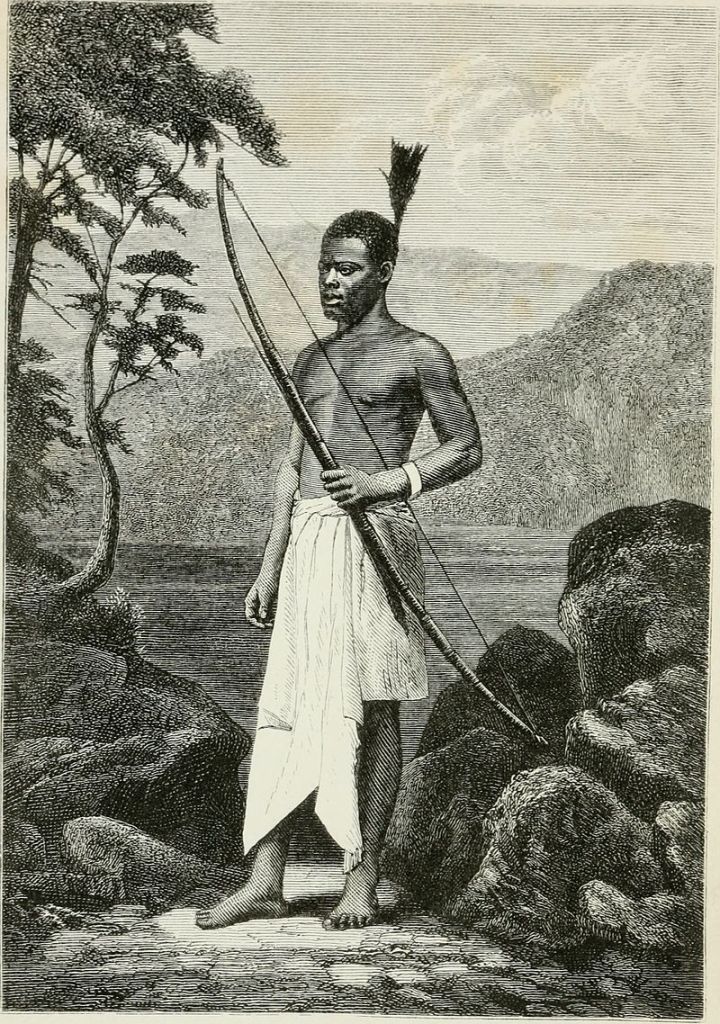

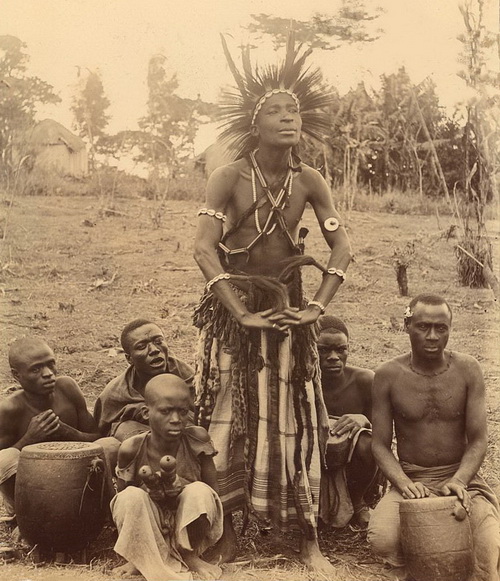

As they near Marongwe’s village they saw a caravan of Yao with their captives. The Kololo (see right) and men of Senna who had accompanied Livingstone from the Zambezi and the Mang’anja who had come with them from Chigunda’s rushed ahead firing their guns.

The Yao ran off and another forty-three slaves were freed and added to the Bishop’s congregation.

Livingstone tells the story a little differently:

“A long line of Ajawa warriors, with their captives, coming round the hill-side. The first of the returning conquerors were entering their own village below, and we heard women welcoming them back with “lillilooings.” The Ajawa headman left the path on seeing us, and stood on an anthill to obtain a complete view of our party. We called out that we had come to have an interview with them, but some of the Manganja who followed us shouted “Our Chibisa is come:” Chibisa being well known as a great conjurer and general. The Ajawa ran off yelling and screaming, “Nkondo! Nkondo!” (War! War!)

We heard the words of the Manganja, but they did not strike us at the moment as neutralizing all our assertions of peace …….. and a large body of armed men came running up from the village, and in a few seconds they were all around us, though mostly concealed by the projecting rocks and long grass. In vain we protested that we had not come to fight, but to talk with them. They would not listen, having, as we remembered afterwards, good reason, in the cry of “Our Chibisa.” Flushed with recent victory over three villages, and confident of an easy triumph over a mere handful of men, they began to shoot their poisoned arrows, sending them with great force upwards of a hundred yards, and wounding one of our followers through the arm.

Our retiring slowly up the ascent from the village only made them more eager to prevent our escape; and, in the belief that this retreat was evidence of fear, they closed upon us in bloodthirsty fury. Some came within fifty yards, dancing hideously; others having quite surrounded us, and availing themselves of the rocks and long grass hard by, were intent on cutting us off, while others made off with their women and a large body of slaves.

Four were armed with muskets, and we were obliged in self-defence to return their fire and drive them off. When they saw the range of rifles, they very soon desisted, and ran away; but some shouted to us from the hills the consoling intimation, that they would follow, and kill us where we slept. “

The British men present at this first armed conflict with slavers knew that this was a significant event that changed the relationship between the explorers, missionaries and the inhabitants of the Shire Highlands. In Livingstone’s memoir he declines to accept any responsibility for the action and blames the Mang’anja for calling out their war cry.

Intriguingly the excerpt from Mackenzie’s letter written on the 22nd July gives a very brief description of the event saying anything longer “would weary you”.

He writes:

“On our way towards meeting the Ajawa, and meeting many persons running away from the war, we learned at one village that some Tette people who had come up to buy captives yesterday, were on their return, with a great many slaves, and were close at hand : having got one or two natives to shew us where they were, we turned aside, and after two miles’ march came upon them, freed more than forty captives, and took three Tette slavers prisoners.”

Doctor John Kirk had returned to their boat on the Shire that had been left below Murchison’s Cateracts and missed the action on the 22nd so his report is second hand but is still interesting in its detail.

“The Bajawa seeing the party coming down the hill, threw away the booty they were taking their camp and fled. The Ajawa camp was in a very strong position. The pass is precipitous and strewn with rocks, which the Ajawa manned and sent poisoned arrows on our party. These were soon driven out and cleared.

There in front, lay the village on both sides of a ridge, the people first scattered and then on our party retiring, in order to induce them to come to terms, they rushed back, thinking it was a retreat. The fire now began in earnest. The Ajawa danced about and cut capers, firing their arrows with tolerable aim at 100 yards. None however struck except one in the arm of a Manganja, one of those who accompanied. The rifles took down about 6 men. The Makololo and Senna men took down 2 of these. The Ajawa fled to the hills while DR. L burned the village.”

It is interesting to compare the three reports, not so much in the differences in the detail but more the contrasting tone. Livingstone is keen to blame the Kololo and the Man’anja for starting the fight; the Bishop skims over the whole event and merely reports freeing another forty slaves: whilst Kirk gives a seemingly straight forward, factual report.

It is if both Livingstone and Makenzie are washing their hands of this first conflict with the Yao despite it being clear that it was their decision that drew them into direct action.

Soon after Livingstone and his expedition party left the mission and headed south to return to their boat on the Shire.

The Militant Bishop and the Second Battle

Magomero now has a population of 184 people the majority of whom are freed slaves.

The mission party set about laying out, what is now becoming a village, and building the stockade and huts.

Mackenzie is in his element, planning the mission station and beginning his work of civilising his flock before converting them to Christianity.

The senior chief of Mang’anja in the area was Chisunzi and he and some of his sub-chiefs visited the mission asking them to intercede with the Yao who continued to raid Mang’anja villages. Livingstone, before leaving, had counselled the Bishop not to become involved in the conflicts between tribes but, from Mackenzie’s perspective, the petitions from the Mang’anja and the atrocities being committed by the Yao were both becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

On August 7th Chisunzi brought his two most senior sub-chiefs; Kankhoma from west of Lake Chilwa and Barwe who was local to Magomero, and 150 other men whom Henry Rowley believed were also people in authority, perhaps elders or village headmen. A great conference, which Rowley says could not have been any more decorous or better ordered, was held close to the Bishop’s hut.

Chisunzi’s spokesmen described the blissful state of the country before the Yao had arrived and then:

“They spoke of villages burnt, of brethren slain, of wives and children carried away; and they concluded by describing the happy state of things that would again exist, if the English would only help them against their cruel enemies.”

Bishop Mackenzie told the delegation that he would take three days to consider their request. After Holy Communion on the following Sunday the missionaries conferred. They were conscious that to become involved would cause issues with the Church at home but they dealt with the problem of clergymen taking up arms and shedding blood by rationalising that in a civilised country they wouldn’t build their own huts either and there would be a civil authority to take such action.

Their decision to help the Mang’anja was unanimous and so the Universities Mission voted to go to war.

At the second great conference the Bishop told the Mang’anja that he would fight the Yao if the chiefs agreed to four conditions. In essence the conditions were that the Mang’anja would not engage in slave trading and would punish anyone who did, that captive slaves freed in the fight with the Yao were indeed free and could choose where they went and finally that the Mang’anja would drive off any Portuguese or other foreigners who arrived in their lands. The chiefs agreed but as any good lawyer knows the devil is in the detail and there were different perspectives on what had been agreed.

On August 13th The Bishop led out, the Reverend Rowley, Horace Waller, Scudamore the carpenter, Adams another layman, Hardisty the engineer, Gwillim the quartermaster, Hutchins a sailor, Johnson their black cook and Charles who had come up with them from the Cape. they were accompanied by around fifty of Chigunda’s men.

They were to join Chisunzi’s men in their village near Ulumba Hill south of Zomba. After their arrival various groups of Mang’anja drifted in until there were about 1,000 men in the village but even the few that had firearms had no ammunition so the main weapons were spears. The plan was to attack the substantial Yao village of Chilumba which was a spread out affair stretching from east of Ulumba to the slopes of Zomba the main Yao camp on the southern slopes of Mount Zomba.

Chisunzi wanted them to leave at midnight to ensure the Yao were surprised. The Bishop refused and agreed only to leave in the morning.

They rose at 4 am and when the order came to match pandemonium broke out as everyone tried to get out at through the single file exit from the village at the same time. Once order was resumed the English led the assembled force out of the village in single file.

More Mang’anja joined them as they marched towards Zomba. When they neared the Yao camp the Bishop held a prayer service and leaving the force under the command of the Reverend Rowley he went ahead to parley with the Yao. Chisunzi’s plan of catching the enemy by surprise had been ignored by the Bishop.

Naievly the Bishop assumed the Yao knew the rules of chivalry but in practice he only got back alive because the three Yao he met ignored orders being shouted down to them to kill the English. Failing in his peace mission the Bishop withdrew and the British Mang’anja force attacked.

The Battle of Sasi Hill, Zomba 14th August 1861

The main body of the British and Mang’anja force had waited for the Bishop on a hill overlooking the Likangala Valley just south of present day Zomba. The Yao settlement was spread out along the valley and onto the slopes of Mount Zomba with the chief’s camp to the British left. To their front the Yao held a defensive position on Sasi Hill which lay on the other side of the valley in front of Mount Zomba. The parley had given the Yao in the valley time to move towards the chief’s camp and to reinforce the hill.

MacKenzie placed Waller in command and he ordered Gwillim and Hutchins to take Kakarara Kabana and his men and move behind Sasi Hill to come upon the Yao from their rear.

After giving Gwillim time to get behind Sasi Hill, Waller ordered a general advance down into the valley. They immediately came under fire from Yao warriors hiding in long grass but return fire soon cleared their path.

As they reached the huts in the valley the Mang’anja stopped to set them on fire as the Bishop began a first assault on Sasi Hill. He came under fire from the defenders and returned fire driving the Yao warriors back. But the Bishop realised that they were at risk of becoming isolated and sent Rowley back to bring up the Mang’anja who were still near the burning huts making a lot of noise but not advancing.

Meanwhile Gwillim and Hutchins had engaged with a large group of Yao who were coming round the back of Sasi Hill in the opposite direction in an attempt to outflank the British. The two missionaries and Kakarara Kabana’s men held them off and the Yao were forced to retreat.

Rowley moved forward to support the Bishop’s assault on Sasi Hill but was engaged by a group of Yao who quickly retreated to increase the defenders on the hill. Gwillim had joined Rowley by this point and passed his Enfield rifle to the good Reverend suggesting that he lay down fire to support the assault. Rowley set the sights to 600 yards and fired two shots over the heads of the defenders. The Yao were so shocked to be fired on from such long range that they ran from the hill.

With the hill in British hands the battle was as good as over but the Bishop along with Waller, Scudamore and Hardistry attacked and destroyed the chief’s camp before each taking a troop of Mang’anja and proceeding to clear the valley.

The Yao were in full retreat down the road to Lake Shirwa; it was beginning to rain heavily and the British had mostly lost contact with each other. In two’s and three’s along with the Mang’anja, and eighty women and children they disengaged and began to trudge back to Chisunzi’s. They finally sat down to rest and eat at about 8 o’clock, sixteen hours after setting out.

However, the eighty women and children were a mixture of Mang’anja, who had been held captive, and Yao wives and children. There were also children of Yao men and Mang’anja women and some freed captives from a completely different tribal group. This caused much confusion and argument amongst the chiefs and the Bishop and in the end the Yao women joined the Magomero mission and the freed Mang’anja women chose new protectors amongst the chiefs and their men.

The Battle of Sasi Hill had involved a significant number of men. We know of the 8 British missionaries, their two African servants and over a 1,000 Mang’anja and given the scale of the Yao settlement perhaps a similar number of Yao. We also know that the Yao settlement contained women and children as well as a few captive slaves. However, Rowley believed that no more than five Yao were killed and that these had fallen when the Mang’anja caught up with the rear of the retreat.

Rowley is convinced the events of that day were worthwhile as he says:

“By what we did I have no doubt we saved, for a time, many hundreds from death or slavery, for after these events no slave-trader came within many miles of our station.”

The Bishop was even more effusive:

“The direct effect of the two attacks has been the pacification of a wide extent of the country, nearly a thousand square miles which was constantly suffering from the outrages of these marauders.”

The missionaries continued to have a naive and general incorrect view of the local situation. The Yao were not raiding, they were settling south of Lake Malawi under pressure from the Ngoni who were moving into the area around the lake having fled the fast growing Zulu empire in the far south.

The Aftermath

Their self-congratulation was short-lived. The days following the victory at Sasi Hill saw first Barwe, their most local village chief and then Chisunzi with all his sub-chiefs in tow asking the missionaries to chase off a large and well-established Yao settlement near Barwe’s and just 11 kilometres from Magomero.

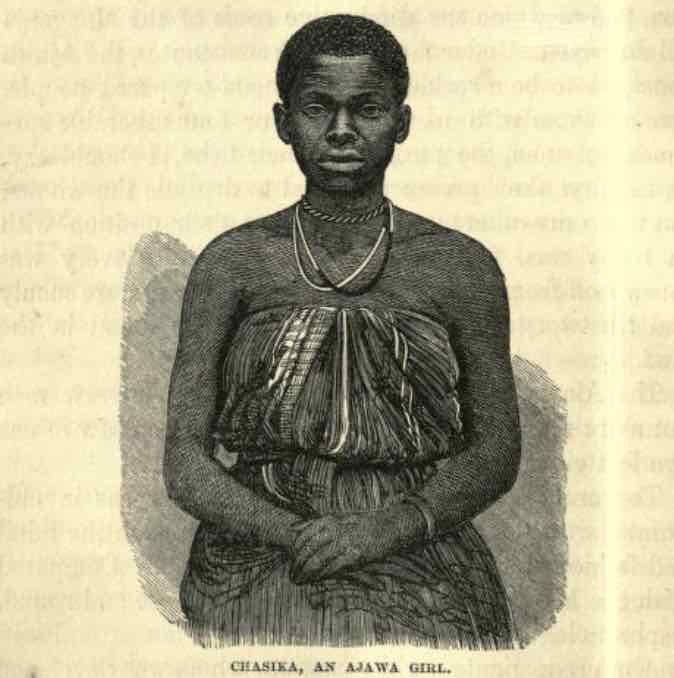

The Yao women at the mission (one is shown left) confirmed that this village has been there for long enough for the Yao to have started gardens.

The Bishop refused to help either delegation.

Having very much nailed their flag to the Mang’anja mast there was another shock in store. The Bishop conducted a poll amongst the freed slaves at the mission and discovered that three quarters were Yao and that more of them were Yao that had been sold to slavers by the Mang’anja than Mang’anja sold by the Yao. They also realised through contact with Chisunzi and his sub-chiefs that the Mang’anja had slaves, including Mang’anja, that they had kept for themselves after the battle at Sasi Hill.

The Bishop was furious, and persuaded the chiefs to hand over all their slaves, but he was beginning to realise that the local situation that he had seen in simple terms of Yao slavers versus Mang’anja victims was more complex and that they had planted the mission right in the middle of it.

More delegations and more reports of Yao incursions arrived and the Bishop decided to go on a tour of inspection visiting Barwe’s, then Chisunzi’s and finally Nampeko’s which was towards Lake Shirwa. Near Barwe’s he saw the settled Yao village and people cultivating their gardens but at Nampeko’s he saw the smoke from burning villages to the north and refugees heading south to escape.

The Bishop once again decided to intervene and he comes up with an ambitious plan to take the Yao occupied, Chikala Hills which lay to the northeast of Zomba. On achieving this military objective he would open a second mission at Nampeko’s to protect the area.

He had not only become war-like but he was fast positioning himself as a colonial power. Landeg White explains that the political map of the Shire Highlands and Shire Valley was not based on relationships between tribes or families but between protector and protected. The Bishop had unintentionally given protection to Chigunda by choosing to build the mission on his land, a mission well equipped with Enfield rifles and determined men. Liberated slaves from Mang’anja, Yao and Nguni tribal groups all chose to stay at the mission for the same reason.

After a false start caused by Nampeko exaggerating the scale of the problem the Bishop takes his rifle and confidently heads off to conquer the Yao in the Chikala Hills. The new campaign is a rude awakening for Mackenzie. They find an empty Yao village which they promptly burn to the ground; they raid the gardens and Adams fires shots at two armed Yao he sees in the distance. According to Rowley, they capture nearly 500 women and children.

On withdrawing to a local Mang’anja village they spent a miserable, cold night hungry and soaked by torrential rain. The captives were offered the choice of where to go and with whom. Most, including a number of Yao, went with the Mang’anja chiefs and the Bishop marched home with 50 more mouths to feed.

Some weeks later the Bishop was drawn into one last armed raid on a village but it has nothing to do with slavery and plays no part in this story.

Following the raid on the Yao of the Chikala Hills everything that could go wrong began to do so. The short-lived mission at Magomero slid slowly but surely into decline. On the 31st January 1862 the Bishop, having managed to upset Chigunda and the senior chief in the Shire Valley, died of malaria in a miserable hut 100 kilometres south of the mission below Elephant Marsh whilst vainly waiting for his sister to be brought up stream .

Magomero suffered famine and disease and many of congregation drifted away. The tough and experienced Kololo, who had been left with them by Livingstone but who had never been allowed to properly settle at Magomero, now departed to settle at Chibisa’s.

The mission’s demise created a power vacuum and Kumpama, the Yao chief who had settled near Barwe’s, the same Yao chief that Barwe had repeatably begged the Bishop to deal with, started raiding as far south as Mbona’s near present day Blantyre.

Mbona, Mbame and Barwe formed a coalition to fight Kumpama and in mid-April 1862 they met in a decisive battle but Kumpama prevailed. On April 23rd the missionaries could see villages, including Barwe’s, burning in the distance and the decision was made to pack up and leave.

Retreat

When the mission packed up and left Magomero for the relative safety of the Shire Highlands and then to a new site at Chibisa’s on the Shire eight more women and children decided to stay at Chigunda’s neighbouring village.

The depleted mission now at Chibisa’s was under threat and increasingly isolated from the Mang’anja villages of the Shire Highlands that had mostly fallen to the Yao. There was also tension with the Kololo who were busy creating a new territory for themselves near Chibisa’s.

In June 1863 their new Bishop, William Tozer, arrived and resolved to withdraw the mission. Bishop Tozer wanted to distance himself from the whole history of the ill-fated mission at Magomero arguing that the release of the slaves from the slave caravan in 1861 had been “highland robbery”. None of the surviving, liberated, slaves had been baptised so, in his mind, they were not his problem and should be left to fend for themselves. After many furious arguments with the surviving missionaries he agreed to set up a school at Morumbala near the River Zambezi for twenty-five orphaned boys but that was his only compromise.

Horace Waller, one of the missionaries, refused to take no for an answer and resigned from the mission and, after a failed attempt to follow Tozer in canoes, stayed at Chibisa’s with thirteen liberated women and their children. They were joined by a few others including Chinsoro and Chasika.

Tozer failed to build his mission station at Morumbala and withdrew to Zanzibar offering to take the orphaned boys with him. Six refused and returned to Chibisa’s and, after yet another argument, Livingstone gained custody of the rest. Livingstone took Waller’s little community and the orphaned boys down the Zambezi to the coast in 1864.

To find out what happened to the freed slaves who joined either Livingstone or Waller see Magomero and the Nasik Boys and Rigby, Livingstone & the UMCA

The Consequences

The Victorians had a crystal clear vision of how society should be organised and the church’s evangelism, their desire to convert the heathen natives of Central Africa to Christianity, went beyond religious dogma as shown by the mission’s objectives that included the desire to instruct those same natives in “the arts of civilised life”, reveal the “mutual benefits” of “lawful commence” and demonstrate “the sinfulness and disastrous consequences of a traffic in human beings.”

The history of religious, political, commercial and social colonisation throughout the 19th and 20th centuries and that still lingers in pockets in the 21st is the idea that “our culture”, in the very broadest sense of the word, is paramount and it is our duty to impose it upon others.

The first direct intervention with the slave trade ended less than a year after it started. The British Victorians were a confident breed, convinced of the rightness of their civilisation, their religion and their culture. They subscribed to the view that the natives of Africa had none of those things. They were incapable of judging people on any terms other than their own so they consistently underestimated and misunderstood every new culture they met.

The Bishop’s refusal to help Barwe is a perfect example. The prim Victorian clergymen could not cope with a young, flamboyant chief who greased his hair into elaborate hairstyles and wore brass rings on his arms and legs. Rowley called him a “great dandy”. They despised and ignored him, even when the senior chief supported him. This prejudice led them to march 60 odd kilometres north to raid the Yao in the Chikala Hills rather than deal with the Yao settlement on their doorstep just 11 kilometres away at Barwe’s.

Perhaps supporting Barwe and chasing off Kumpama before his power grew might have changed the balance of power; perhaps letting the Kokolo establish themselves near the mission would have created a strong anti-slaving presence in the area but the Yao were moving south, they were armed and well organised and apparently more war-like than the Man’anja so perhaps nothing would had altered the end result.

The mission achieved very little, they did free some slaves but, they themselves, questioned how this balanced against separating an equal number of Yao women and children from their menfolk. Relying on Livingstone and Livingstone’s advice was disastrous but this was an unavoidable mistake given the self-professed, African expert’s status and his role as their guide and mentor.

In the fight against slavery perhaps the cleanest, least invasive form of intervention, was the British Navy’s West African anti-slavery squadron and the later Cape Squadron on the East Coast, preventing the trade without directly connecting it to societal change. When the British stepped on African soil with the same objectives they inevitably dragged the baggage of religious, cultural and commercial conversion along with them.

For the next 27 years the Yao dominated the highlands raiding for slaves and trading in slaves and ivory until the British under Sir Harry Johnston supported by his Sikh troops moved into Zomba and declared a British Protectorate over the Shire Highlands in 1889 but that is another story.

Leave a reply to Colonists and Slavery in Malawi Part 1 – Pre-Colonial Africa, The Empty Land – Travelogues and Other Memories Cancel reply