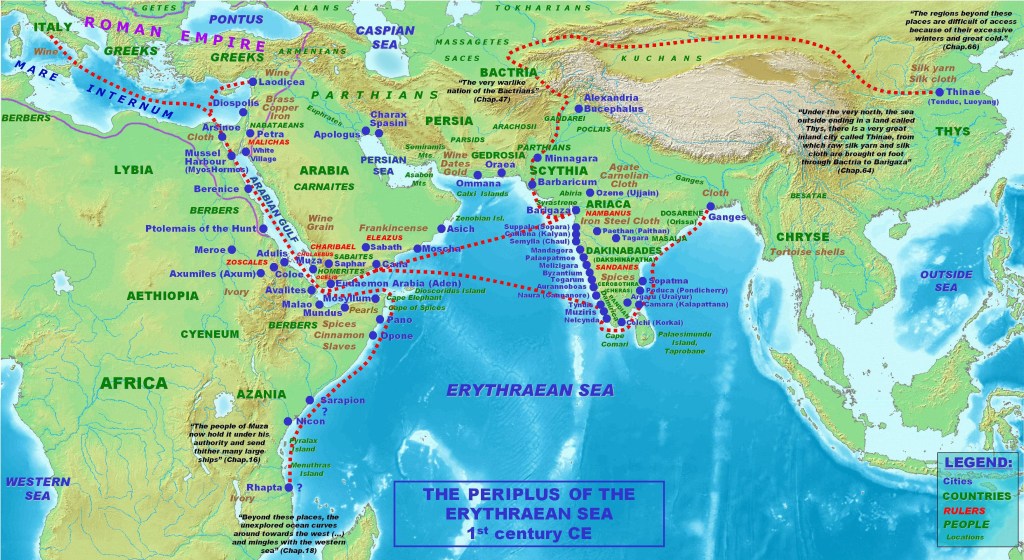

Sometime between 30 and 40 AD, when Tiberius or his nephew Caligula was the emperor of Rome, an unknown Greek or Roman merchant wrote a trader’s guide, a “periplus”, to the Indian Ocean. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea covers a huge area, from the Red Sea, east to the Persian Gulf, onwards to the Indian sub-continent and as far east as modern day Bangladesh and Myanmar.

In the other direction it leads traders south round the Horn of Africa and down past the east coast of Africa. It notes landmarks as an aid to navigation and describes anchorages and ports and the trading opportunities that can be found there.

At the furthest point south on the East African coast it describes Menouthias and Rhapta which are believed to be the earliest documented mentions of Pemba, the island just North of Zanzibar, and Dar es Salaam. The Periplus says that here the first-century merchant could trade for “great quantities of ivory and tortoise shell” as well as metalwork such as spears, knives and awls with the “very big bodied men who live here”. Most interestingly it says:

“The region is under the rule of the governor of Mapharitis1, since by some ancient right it is subject to the kingdom of Arabia as first constituted. The merchants of Muza hold it through a grant from the king and collect taxes from it. They send out to it merchant craft that they staff mostly with Arab skippers and agents who, through continual intercourse and intermarriage, are familiar with the area and its language.”

Remarkably two thousand years ago, the coast of Tanzania was not only attracting traders from the civilisations of the Mediterranean but Arab merchants had already settled and intermarried here and through them Bantu-speaking migrants from west Africa and southern African pastoralists were trading with Arabia and across the Indian Ocean.

The Periplus in the first-century and Ptolemy’s Geography in the second show the trade routes from what is now the coast of Tanzania and its islands to Arabia, the Middle East, India, Sri Lanka and beyond have been followed for at least 2,000 years.

Nature created this great maritime highway; in October and November cold air is drawn from the Himalayas and blows across the Arabian Sea accompanied by the monsoon current traveling anti-clockwise around the southern coast of Arabia and south down the east coast of Africa; it carried merchants from India and Sri Lanka to Arabia and from Arabia to the Swahili coast: Malinda, Mobassa, Zanzibar and Kilwa, then further south to Mozambique and Sofala.

From June to September the wind and current is reversed as the Indian sub-continent heats up and air is sucked towards southern Asia. The south-east monsoon which carries rains to India and beyond also carried merchants north from the Swahili coast to Arabia, western India and on into the Bay of Bengal.

The north-east monsoon carried merchants laden with cotton textiles and spices and they returned on the south-east monsoon with ivory, gold, cocoa-nuts, copal, spices and slaves.

An important feature of these monsoon-dependant trade routes was that traders would sail down to the Swahili Coast in December and, because of the winds, not return until May.

The evolution of the people, language and culture of this coast arose from these long stop-overs; the Periplus tells us merchants were settling and intermarrying as early as the first-century so African pastoralist, west African Bantu, Persian, Indian and Arab genes, language, culture, and after the seventh-century, religion all combined to create the Swahili, a unique coast-dwelling peoples whose language today, is probably the most widely spoken African language and among the ten most common languages in the world.

Origins of the Slave Trade

The origins of slavery in Africa are ancient; there is evidence that foreign prisoners of war were enslaved in Egypt at the time of the Old Kingdom (2700 BC to 2200 BC) and slavery features in the legal system of Mesopotamian civilisations as early as 1750 BC.

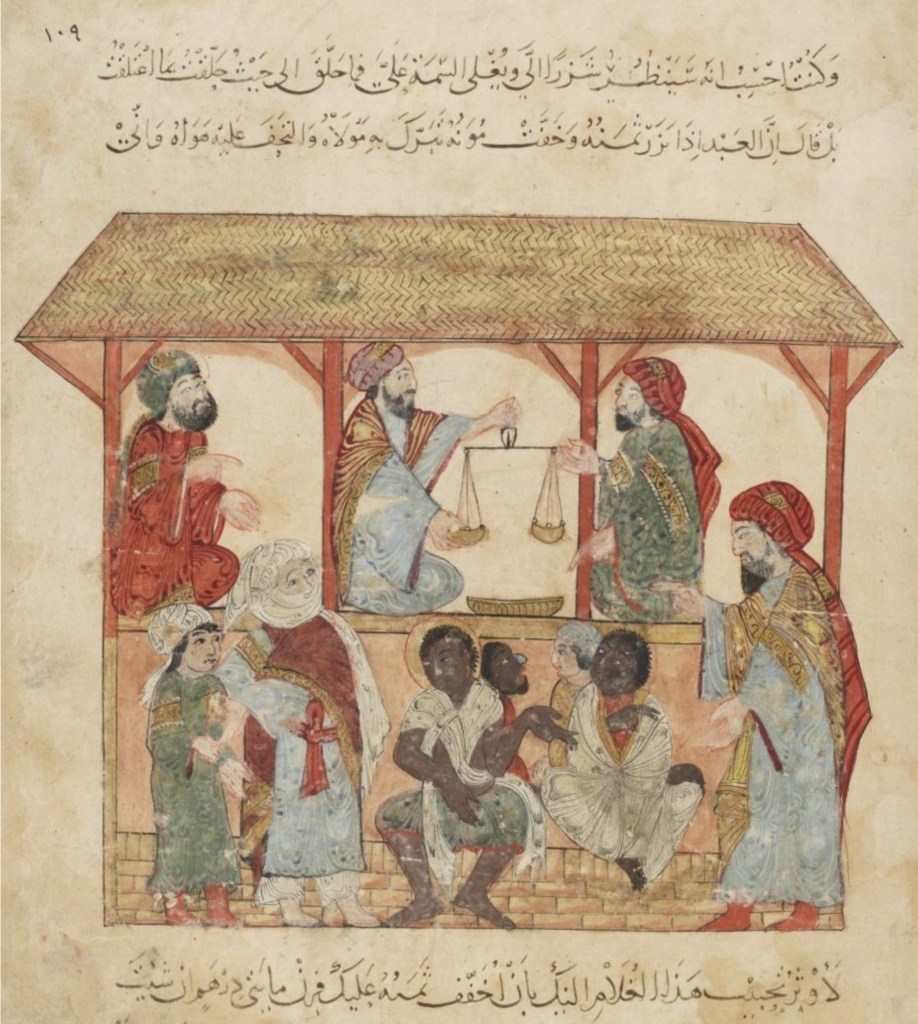

The Periplus mentions slave markets on the coast of modern-day Somalia in the first-century and by the seventh-century Bantu slaves, Zanj, were serving in Arabian armies and were known to make ideal agricultural workers. There is very little documentary evidence regarding the east African slave trade before the Portuguese arrive on the coast in the sixteenth-century. Ibn Battutah, 2 who visited Kilwa in 1331 refers to slaves being in the town but makes no mention of trading.

So, whilst African slaves were definitely present in Arabia, the Persian Gulf and Indian prior to the fifteenth-century we have no real idea of numbers or how active the Swahili Coast trade might have been.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Portuguese left an increasing amount of evidence of the trade but, at that time, they were mostly interested in gold and ivory.

However, there was steady demand from Arabia for domestic slaves, concubines, guards, soldiers, agricultural workers and pearl divers and it appears that a triangular trade route developed in the sixteenth-century between the Swahili Coast, Madagascar and the Comoros with slaves from Madagascar being sold to the Swahili Coast and via the Comoros to Arabia. As previously discussed strong trade routes already existed between the Swahili Coast and the Middle East and there is evidence that slaves were being exported, and perhaps these were Madagascan slaves being re-exported, to the Red-Sea, Egypt and Arabia at this time.

Starting in the late sixteenth-century Portugal was taking a small number slaves from modern-day Mozambique with Swahili traders obtaining some slaves from the interior but, as discussed in a previous blog, 3 the predominant trade on this coast at this time was ivory and all the while there were elephant herds near the coast there was no need to travel deep into the interior for ivory and hence no need for slave porters to bring the ivory out.

The Swahili people living on the coast were traders and rarely appear to have possessed any military might; they avoided conflict with their Bantu neighbours and no Swahili slave-trade routes developed with the interior before the eighteenth-century.

However, in the seventeenth-century the Portuguese began to ramp up their activities obtaining an increasingly larger number of slaves from modern-day Mozambique as well as buying slaves from Madagascar, Zanzibar and from Swahili traders north of Kilwa.

These slaves were destined for Portuguese colonies in the Indies or kept as labourers and servants for Portuguese settlers on the east African coast.

The trade grew rapidly in the eighteenth century with demand from the old markets of India, Arabia and the Persian Gulf but also from the French islands of Mauritius and Réunion. Ever since the Portuguese had arrived on the coast there had been a small number of slaves transported round the Cape but in the eighteenth-century this grew into substantial trade with the Portuguese supplying plantations in Brazil and the French supplying their West Indian colonies. In 1789 about 46 ships, carrying 16,000 slaves rounded the Cape mostly bound for St Domingue. 4

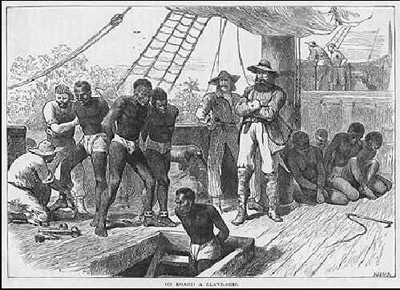

Some writers have argued that the east African slave trade was somehow less inhumane that its west African counterpart and there is good evidence that the Arab dhows carrying slaves north generally treated the slaves comparatively well; they were not shackled and were fed on the same rations as the crew.

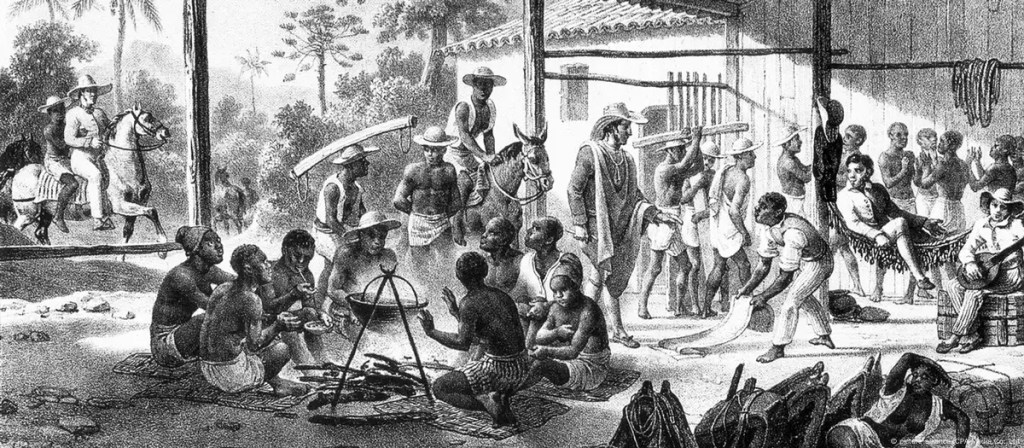

In Faits relatifs à la traite des Noirs, Impr. de Crapelet, 1826.

Collection of Departmental Archives of Reunion Island

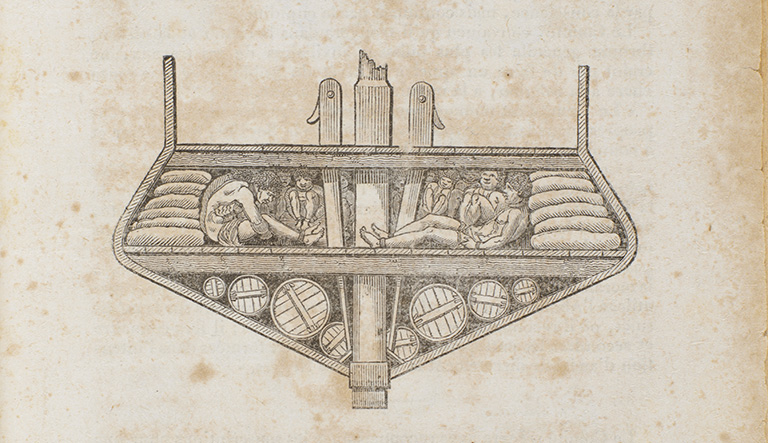

However, the French and Portuguese slavers heading south from Mozambique and Madagascar were slaving ships along the same lines as the trans-Atlantic slavers. Conditions on board were atrocious and mortality rates high. Many slaves were sold en-route to the Dutch colony at Cape Town and when the British occupied the Cape in 1808 they librated 10,000 slaves in addition to the descendants of 30,000 slaves shipped there from Madagascar and east Africa and as many again from south Asia and Indonesia. Landeg White says that it is estimated that, by 1842, the Portuguese had drained upwards of 300,000 men and boys from the Zambezi Valley and shipped them to Brazil, Cuba, the islands in the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. 5

Delagoa Bay, modern-day Maputo Bay, lies less than 100 kilometres from the South African border in southern Mozambique. It had changed hands several times since the Portuguese first arrived there in 1503 6 but for four hundred years there had generally been a small trading post here attracting slave and ivory caravans from the interior. Between 1652 and 1808 it is estimated that around 16,000 slaves were imported into the Dutch colony at the Cape from Mozambique and a similar number for Madagascar. 7

The Delagoa Bay slave market expanded in the early nineteenth-century to meet demand from Portugal’s plantations in Brazil and France’s colonies on the Mascarene Islands.

Lord Brougham in a speech to the British Parliament 8 stated that, despite Brazil declaring the slave trade illegal in 1831 vast numbers of slaves were still being shipped to Brazil; 123,000 in the four years between 1829 and 1836 and a further 109,000 in the next three years. One-fifth of all the slave ships arriving in Rio de Janeiro in the 1830s and 40s had set out from Mozambique. Ships typically carried around 550 slaves and expected a mortality rate of 12% during the voyage.

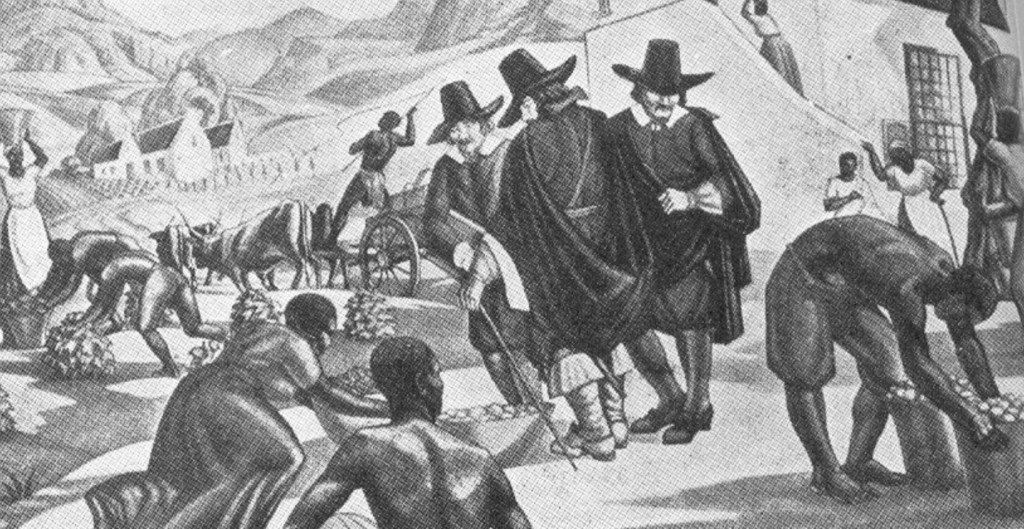

By Fenous 9

By the beginning of the nineteenth-century the slave trade was the dominant economic activity in Portuguese Mozambique with slaves being traded to meet local demand and for export to the Americas including the southern US, Brazil, Cuba and the slave markets of Madagascar. 10 In addition the French were buying large numbers of slaves from the Portuguese, the Swahili coast and from Madagascar to supply plantations on the Mascarene islands and the Seychelles. Over 150 years as many as 300,000 slaves made this trip and more than half had originated at either Kilwa or Mozambique; up to 70,000 of those slaves arrived between 1811 and 1848. 11

As discussed in The Demise of Malawi’s Elephants the ivory trade boomed in the eighteenth-century and along with it the slave trade. Oman had become the primary trading partner with the Swahili coast and the development of huge date plantations created strong demand for slave labour as well as the traditional demand across Arabia for concubines, sailors, servants and pearl divers. Muscat became an important trading hub and was the main redistribution point in the Persian Gulf for slaves and ivory.

Painting by David Roberts

Oman now dominated the Swahili Coast having evicted the Portuguese in 1698 and they established garrisons and factories in Kilwa, Zanzibar, Pemba, Mombasa and Pate primarily to control the ivory trade. Madagascar’s slave-trade declined around this time and the Omani were trading for ivory and slaves with the Portuguese and Yao in Mozambique and the Swahili ports further north. It appears that the second half of the eighteenth-century is the period when the Swahili traders started to acquire slaves to be sold to the market in Muscat and to meet French demand; the slave-trade on the east coast developed to become the second largest industry after ivory.

In 1804 Sayyid Said, the Sultan of Muscat, began to encourage merchants to move to Zanzibar and expand Muscat’s trade with mainland Africa, ivory and slaves being the most important commodities.

In 1840 he moved his whole court to Zanzibar having realised that there was a significant opportunity to develop trade with the interior of central Africa.

Zanzibar had deep harbours, an inexhaustible supply of fresh water and was in a strategic and easily defended location. Sayyid Said recognised that it could be developed as the major trading port serving the Swahili Coast.

Zanzibar had fertile soil and Sayyid Said was a major force behind establishing clove plantations on Zanzibar and Pemba. He recognised that his fellow countrymen would sail their dhows to and from this centre but were less well equipped to be the entrepreneurs who could built the permanent, land-based commercial centre he envisioned and to that end he attracted the Indian merchants who had trading links with Muscat to settle at Zanzibar.

Everything was in place to turbo-charge the ivory, slave and spice trade routes around the Indian Ocean. At the beginning of the nineteenth-century around 40,000 African people were being sold as slaves in the market at Zanzibar every year. By the 1860’s the clove plantations on Zanzibar and Pemba alone needed 10,000 additional slaves annually and by then the market may have been handling as many as 70,000 slaves a year.

The East African Slave trade now reached far inland across modern-day Mozambique and Tanzania through Malawi and Zambia and into the Congo Basin.

Swahili traders and Yao people migrated inland and established themselves from Lake Malawi to Lake Tanganyika whilst the most ambitious, such as Tippu Tip, carved out small empires in the Congo Basin.

There is a seemingly endless debate about how many Africans were traded as part of the East African slave trade. In his book Le Génocide Voilé, the Veiled Genocide, Tidiane N’Diaye, a Senegalese anthropologist, argues that the slave trade into the Arab and Persian world lasted thirteen centuries without interruption.

N’Diaye believes the trans-Saharan and east African slave trade had an even more devastating impact on Africa that the trans-Atlantic trade because so much of the trade involved the castration of men and boys; he believes this barbaric practice killed 70% to 80% of the slaves castrated. Those who survived were deprived of descendants and disappeared from history after they left Africa.

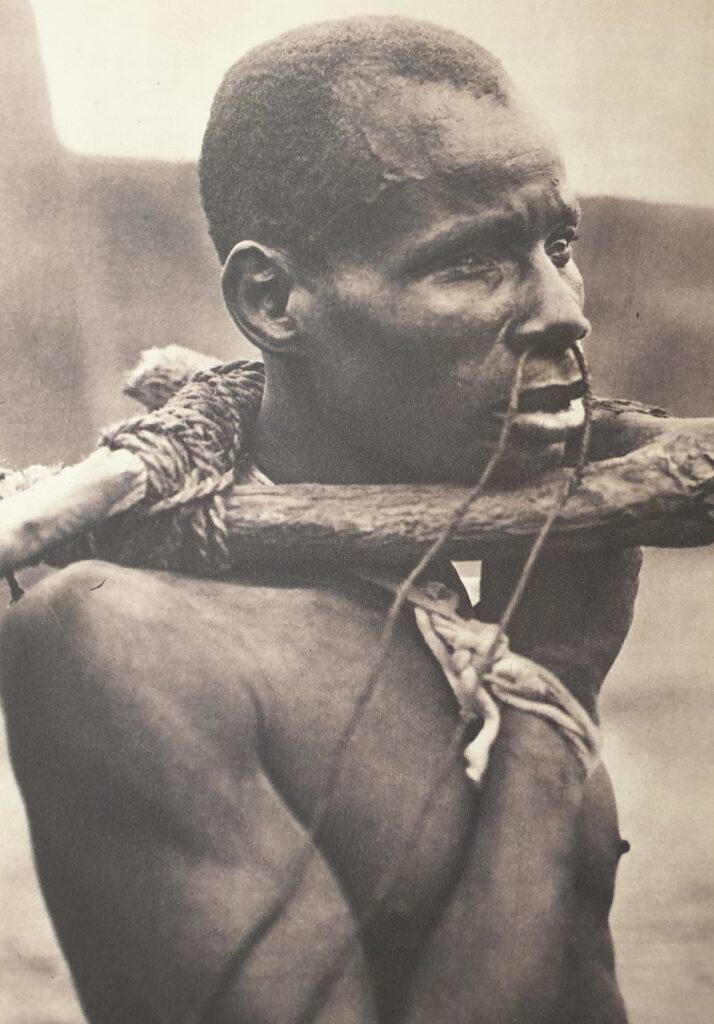

Livingstone believed that only one in six slaves survived the journey from the interior to the coast; other estimates put the survival rate at 20%; so if we take these two ideas into account the number of slaves estimated to have been sold in Zanzibar each year becomes an irrelevant statistic.

If a 100 men or boys entered a castration centre in the Congo Basin or the Luangwa Valley maybe at best, 30 survived; between their start point and the coast they would have walked for months to reach pens at Karonga or Nkhotakota, held until there were enough slaves to fill a dhow, sailed across lake Malawi and walked a further four months to the coast. At Kilwa they are transported by sea to Zanzibar where they are finally sold. Of the original 100 men and boys there are perhaps 5 or 6 left alive.

In 1807 Britain passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act which made British involvement in the slave trade illegal. In 1833 Britain passed the Abolition of Slavery Act which began the gradual abolition of slavery in all British colonies.

Abolition was powered by public opinion following long campaigns by abolitionists strongly supported by the Church. But the British establishment had already recognised that Britain’s long term commercial and political interests were best served, not just by stopping Britain’s involvement in slavery, but by being seen to lead the fight to stamp out the slave trade and abolish slavery on land and sea across the world.

The Bishop of Oxford in November 1859 captured the public mood:

“England can never be clear from the guilt of her long continued slave trade till Africa is free, civilised and Christian”

For the Church it was a penance, for the Government it was a cause that advertised the high ideals, morality and good intentions of the Empire and provided instant moral ascendancy over any country that had not abolished the trade.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Macpherson Collection

It was cause that sent the Royal Navy to hunt and stop slavers off the coast of west Africa. In 1808 there were just two ships based at Portsmouth but by the 1840s 25 ships and 2,000 men of the Royal Navy plus 1,000 Kroomen 12 were engaged in anti-slavery activities.

In 1842 the initiative was extended to the east coast. The British government sent one frigate, four sloops and three or four brigs to patrol the Swahili coast. Landeg White says it was ineffective to stem the flow of slaves north but that is a story for another day.

Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Footnotes

- Al-Hujariah, also known as Mikhlaf al-Maʿafir and Mapharitis, is a mountainous region in southwestern Yemen. ↩︎

- Ibn Battuta (1304 to c.1368) was a great medieval traveler who reached as far south as Kilwa on the east African coast as well as China and Indonesia in the far east. ↩︎

- See https://travelogues.uk/2024/05/31/the-fall-rise-of-malawis-elephants-part-2-the-nightmare-years/ ↩︎

- Quoted from a Smithsonian Fact Sheet “In 1794, the São José, a Portuguese slave ship, was wrecked near the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. Destined for Brazil, the ship was carrying more than 400 slaves from Mozambique when it struck a rock and began to sink. The crew and some of those enslaved were able to make it safely to shore, but tragically, more than half of the enslaved people aboard died in the rough waters.

The São José left Lisbon April 27, 1794, to purchase slaves in Mozambique, with the intent to continue on to Brazil. The Cape of Good Hope in South Africa had long been supplied with enslaved people from parts of East Africa, but beginning in the 1790s, East Africa also became a significant source of slaves for the Brazilian sugar plantations. The São José was one of the earliest voyages of the slave trade between Mozambique and Brazil, a massive trade in human beings, which continued well into the 19th century. More than 400,000 East Africans are estimated to have made the journey between 1800 and 1865, transported in inhumane conditions in voyages that often took two to three months; many did not survive the trip. For many years Cape Town prospered as a way station for this trade before ships began their long trans-Atlantic journey”.https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/factsheets/history-s-o-jos-slave-ship-and-site ↩︎ - Landeg White (1987) Magomera: Portrait of an African Village. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 11. ↩︎

- After being first noticed by the Portuguese in 1502 the bay had a long and complicated history with various interactions of a fortified settlement swapping hands between the Portuguese, Dutch, British, the Holy Roman Empire and even, for a very short time in the eighteenth-century, an English pirate. It was always an isolated and unhealthy place swarming with mosquitoes and as a trading centre it experienced more bust than boom but had fairly consistently traded in ivory and a few slaves. ↩︎

- In the same period a similar number of Slaves arrived at the Cape on VOC ships from Indian and Indonesia. ↩︎

- Lord Broughton, Hansard (2nd August 1842) Slave Trade https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1842/aug/02/slave-trade ↩︎

- Fenous, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons ↩︎

- M.D.D. Newitt (1972) Angoche, The Slave Trade and the Portuguese 1844 – 1910 https://www.jstor.org/stable/180760?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↩︎

- Richard B. Allen (2022) Plantation Economy and Slavery in the Mascarene Islands (Indian Ocean) https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-902?p=emailAwBTG91F8qYu2&d=/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-902 ↩︎

- Kroomen were originally natives of Liberia in west Africa and were engaged by the Royal Navy on three year contracts to serve as pilots and seamen on Royal Navy warships. They were expert navigators and boatmen and fiercely opposed the slave trade and became much sought after by Ship’s captains not least to work on the many small boats used to chase dhows inshore. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply