- The Black Explorers

- Sharanpur and The Nasik Boys

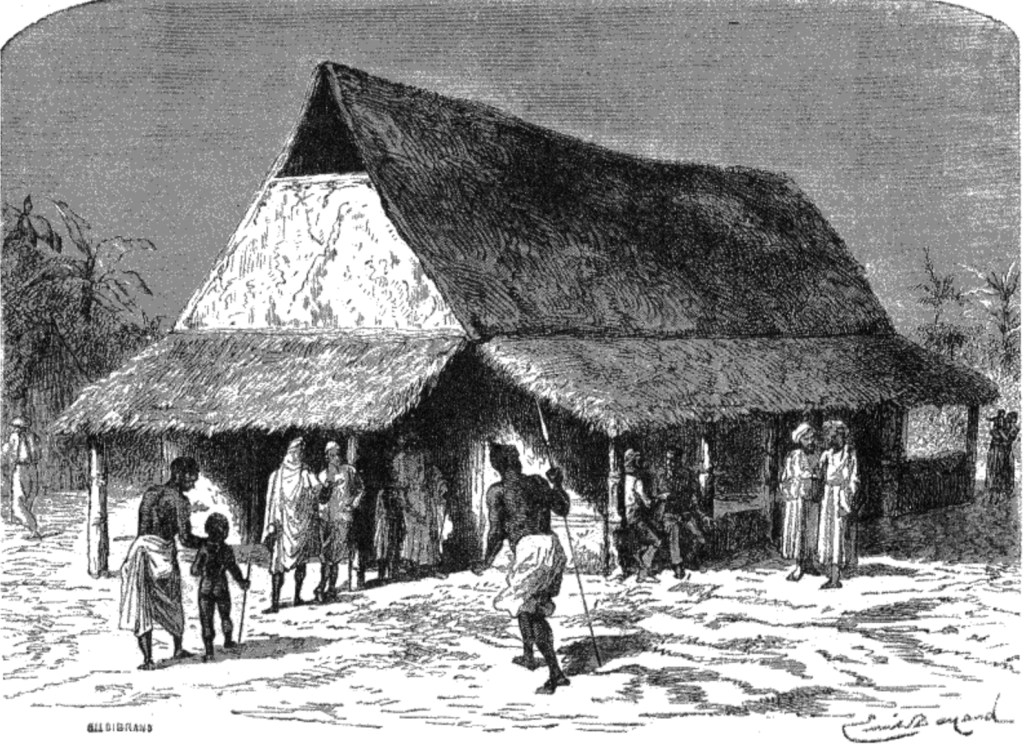

- The Boys Rescued at M’bame’s in 1861

- James Chuma and the 1866 Expedition

- Jacob Wainwright and the Funeral

- Faithful Hands Over Land and Sea

- James Chuma After 1875

- Appendix A

- Footnotes

- Other Sources and Further Reading

The Black Explorers

This is not the story of famous white explorers, it is the story of some of the black African men, boys and women, many of whom were freed slaves, who walked with them. It is often suggested that these people are invisible, have left no trace and are ignored by history and it is true to say their graves in the African bush are unmarked but that was not exceptional in cultures that had no use for graveyards and headstones.

If we look hard enough some, albeit a small minority, have left their mark, scattered across three continents over fifty or sixty years; some wrote their own accounts, others helped Europeans document the stories of exploration, some left oral histories that are still told today, a surprising number were photographed or sketched and a few were recognised as explorers in their own right. Some went on to become caravan leaders and guides and some to become priests and missionaries.

In writing this article and the others in this series I have tried not to write the story of the white adventurers the Africans traveled with but as the Europeans wrote most of the histories it is impossible to keep them to one side. But, in reading their accounts in books, letters and diaries it becomes clear that the role of their African companions was mission critical.

In a land where horses and pack animals had little or no resistance to the diseases carried by the tsetse fly the Africans carried everything except the clothes the white man stood up in. They acted as language and cultural interpreters and increasingly as caravan leaders, guides, quartermasters and section leaders, they negotiated for food and shelter, cooked his meals, prepared the camp, gathered firewood, collected water, stood watch at night and taught him which fruits were edible and which plants could be used as medicines.

Given the scale of some expeditions, Henry Stanley’s caravan to cross Africa set off with three-hundred people, they were the management structure, the NCO’s to the European officers. And, most significantly, they cared for the Europeans and often carried them when they were ill and, for a white man in central Africa in the nineteenth-century, that was a lot of the time.

Harrison Collection © Scarborough Museums and Galleries 1

Without his black companions few European explorers would have got far out of sight of the coast and even fewer would have returned to tell the tale.

This article mostly focusses on African slaves, often from modern day Malawi and Zambia who were liberated in the Indian Ocean on their way to Arabia. They were predominantly children, some became domestic servants, a few joined the Indian Navy but many were placed in missionary schools in and around Bombay. When they returned to Africa they were known as the Nasik Boys.

Sharanpur and The Nasik Boys

The Church Missionary Society

From the early 1830’s liberated East African slaves were unloaded in India, initially at Karachi and later in Bombay. Sir Bartle Frere, who was Governor of Bombay from 1862 to 1867 wrote:

“…the adults of both sexes were handed over to the police, and generally allowed to go their own way, whilst the children were disposed of among such of the inhabitants as were charitable enough to take them and were judged by the police to be sufficiently respectable to be entrusted with the charge.” 2

However, this process was poorly supervised and many young people found their way to work in the brothels around the port.

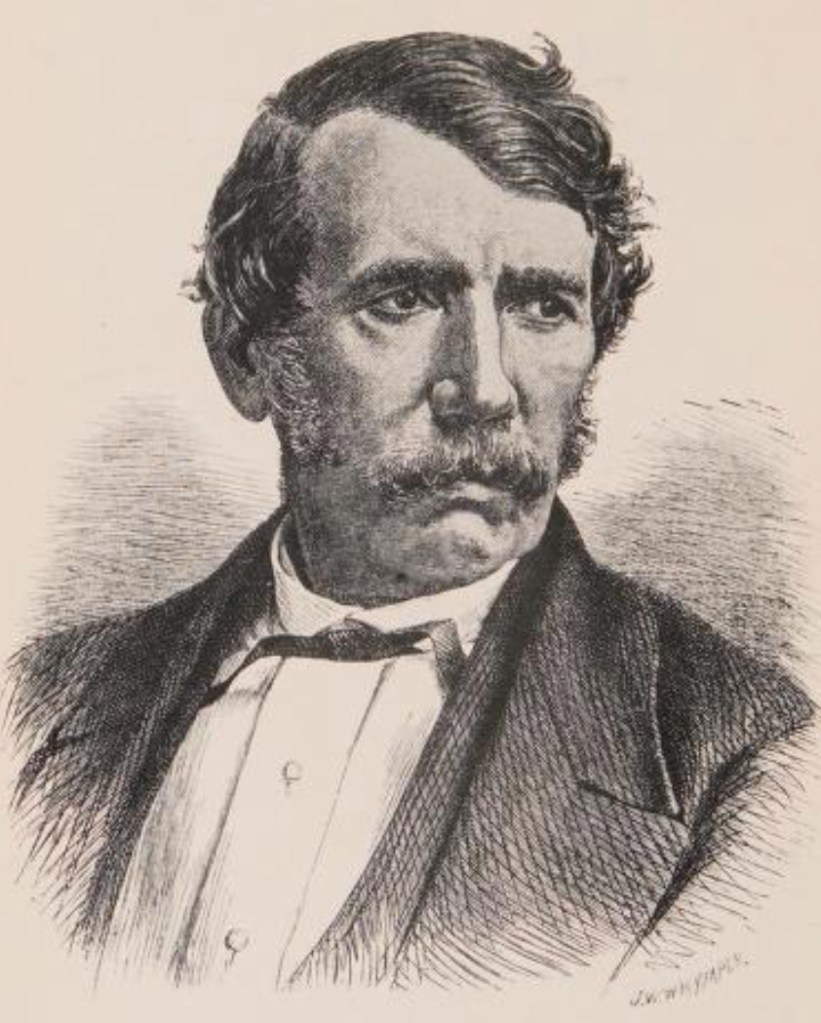

Charles Forjett (see left 3), the Superintendent of the Bombay Police from 1855-63, recognised this problem and when seventy children were captured from a single slave dhow and delivered to Bombay he recommend to the Governor that they should be placed in the mission at Nasik.

In 1854 the Reverend William Salter Price (see left 4), had founded the Church Missionary Society (CMS) mission at Sharanpur near Nashik and about 175 kms northeast of Bombay. It was established as an agricultural and industrial settlement for Indian Christians.

However other sources suggest that liberated African slaves had been taken to Sharanpur long before Frere was Governor.

Towards the end of 1844 Carl Wilhelm Isenberg arrived in Bombay. The thirty-eight year-old German had been ordained by the Church of England and had previously been a missionary in Abyssinia, modern day Ethiopia, where he had been expelled from the country for criticising the practices and beliefs of the Orthodox Church.

In May 1845 he took responsibility for the Robert Money School 5 in Bombay with:

“123 boys and young men, mostly Hindu and Mussulman, but also Israelite, Parsi, and Portuguese Christians.” 6

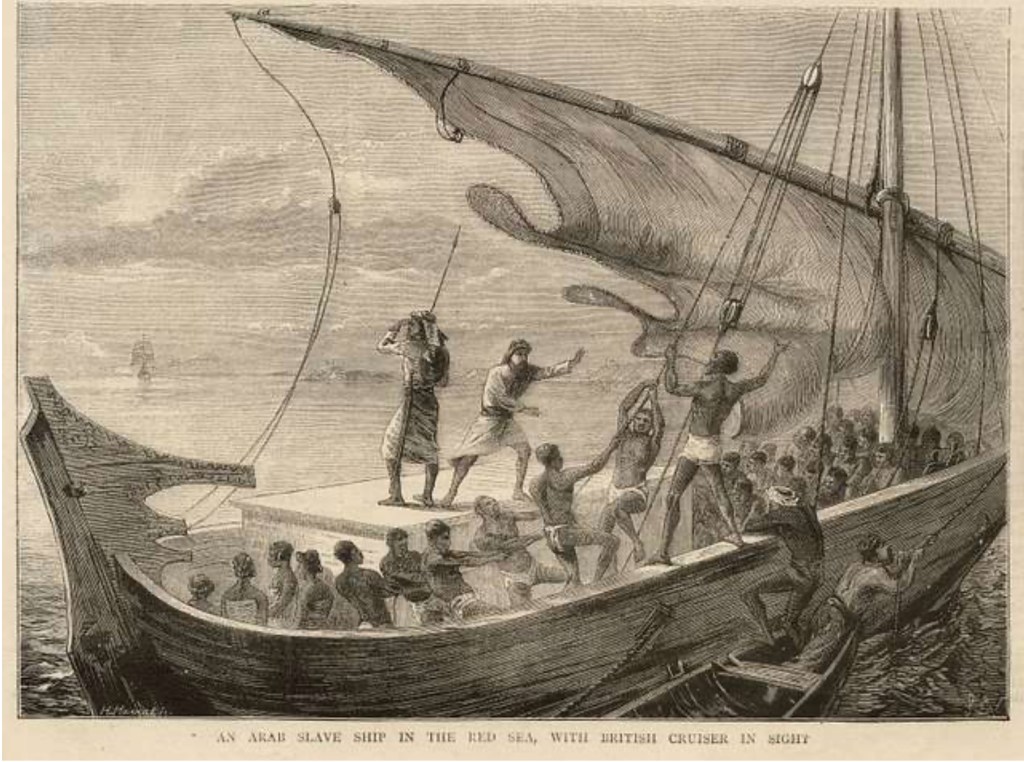

Engraved by Horace Harral 1874

New York Public Library Creative Commons 7

In September 1847 Zenobia 8 an East India Company Indian Navy cruiser incepted five slave dhows in the Persian Gulf and took four women, forty-three girls and twelve boys to Bombay. One of the women was subsequently returned to the Arab traders as she convinced the British that she was one of the captain’s wives.

Isenberg was asked to talk to them and discovered that, whilst some were Swahili, many others spoke Amharic, the language of Abyssinia. He wanted to take them into the care of the mission but the Bombay government refused to countenance the idea. Their, rather thin, argument was they had been taken from an Arab, therefore Islamic, vessel and it would cause offence to educate them as Christians. They suggested that, if they were to do so, then in the future Arab slavers would throw slaves overboard rather than have them captured and “converted” to Christianity. 9

Initially the boys were handed over to the Superintendent of the Indian Navy and the Senior Magistrate in Bombay invited respectable families to take the girls as servants. There were many applications but only one girl was willing to be taken to a Christian family and the magistrate assigned most of them to the households of respectable muslims. 10

Remarkably the Qatar Digital Library contains a 168 page document which includes all the correspondence between the British civil servants, policemen and diplomats involved and, most interestingly, the depositions taken from each liberated slave. The dispositions need to be considered with some care as they are of course written by a British Indian civil servant and not by the slaves themselves.11

However Isenberg was a subversive character and he took it upon himself to maintain contact with the children and over time, and no doubt with his help, most of the children found their way into Christian households where he was able to prepare them for baptism. Throughout the 1850’s more liberated African slaves arriving in Bombay found their way to Isenberg and his congregation was notable for its ethnic diversity.

In 1860 Salter Price left India and when Isenberg assumed responsibility for the settlement at Sharanpur he took with him the African boys he had gathered at the Bombay mission. At the orphanage there were:

“29 African boys, representing eleven nations, mostly Galla and Yao tribes. Hitherto Government had provided for them in Bombay; now they were given into Isenberg’s charge, in order to be trained as mechanics in an industrial school. The older boys were learning the trades of smiths, carpenters, sailors, shoemakers, painters, whilst the younger ones, for whom Government continued to pay certain sums, received a careful elementary instruction.

Special care was taken lest they should forget their own language, in order that they might one day teach their brethren in East Africa what they themselves had learned…… The sounds of the Galla, Swahili, and Yao were constantly heard while they were at their work. After some time it was thought advisable to transfer the African girls of Bombay likewise into this quiet country recess.” 12

In 1863 two of Isenberg’s students, Ishmael Semler and William Jones returned to Africa to work with Johannes Rebmann the veteran missionary based at Rabai, near Mombasa in modern day Kenya.

Ishmael Michael Semler had trained at Sharanpur to be a carpenter. He was ordained in 1885 and retired from the CMS in 1916 after more than 50 years of service.

William Jones went to Rabai with his wife and worked there as a blacksmith.

George and Priscilla David joined them a little later.

The Return of David Livingstone

In September of 1865 David Livingstone arrived back in Bombay in preparation for his expedition to find the source of the Nile. He visited the mission at Sharanpur which was usually referred to as the Nassick or Nasik School by the Victorian writers. By now there were 108 pupils at the school and Livingstone recruited nine “Nasik Boys” at a rate of 5 Rupees a month to accompany him back to Africa.

The original Nasik Boys were:

- Richard Isenberg

- Albert Baraka

- Abraham Pereira

- Simon Price

- James Rutton

- Andrew Powell

- Reuben Smith

- Nathaniel Cumba Mabruki

- Edward Gardner

In April 1864 Livingstone had sailed from the Mouth of the Zambezi to to Bombay in the Lady Nyassa along with seven Zambesians: Chiko, Abdullah Susi, Amoda, Bizenti, Safuri, Nyampinga and Bachoro, 14 who had been selected from a large number who had volunteered to go with him as crew at a rate of 10 shillings a month and two boys from Magomero, Chuma and Wekatani.

They were paid off in Bombay on 22nd June and when Livingstone found them again in 1865, four had died and Chiko wanted to return home, but Abdullah Susi and Amoda agreed to join the expedition to search for the source of the Nile. These two men would stay with Livingstone until his death and help carry his body back to Zanzibar.

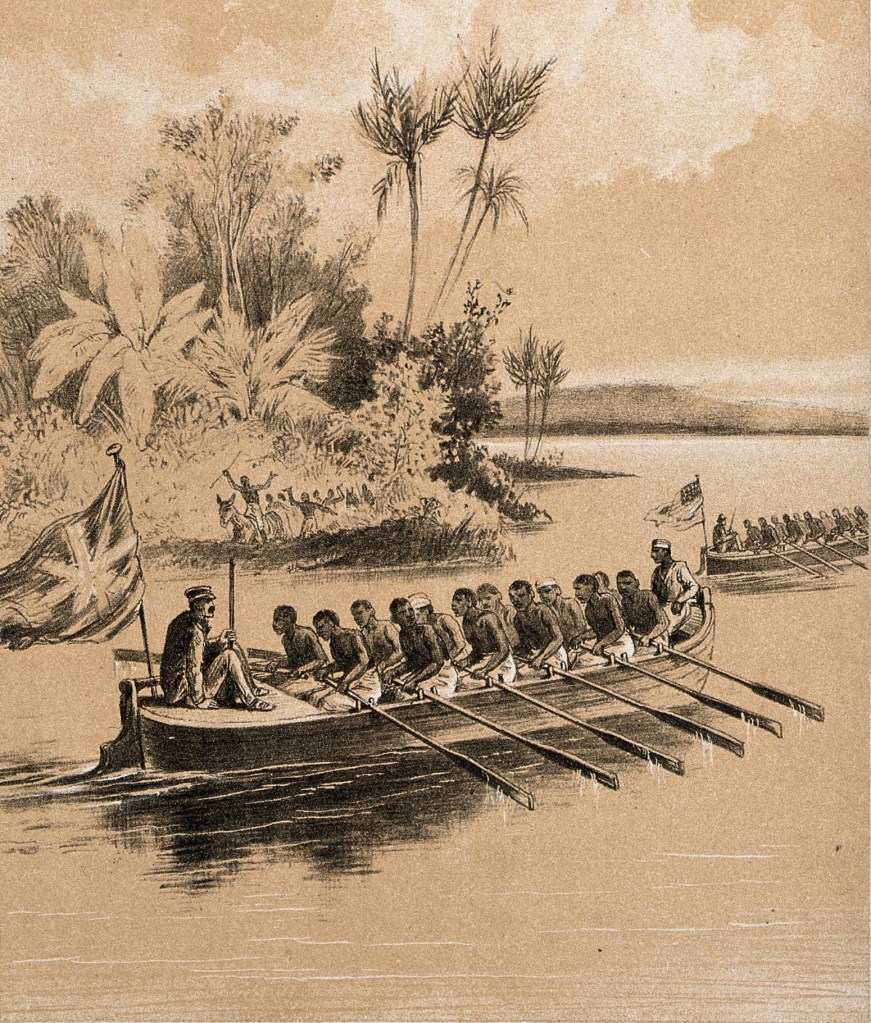

He left Bombay on 5th January 1866 on the Thule with the two Zambesians, nine Nasik Boys, James Chuma, John Wekatani, a havildar15 and twelve sepoys16 who had previously served in the marine battalion of the Indian Navy.

The Sepoys turned out to be a great disappointment and by June ’66, only three months from the coast, Livingstone dismissed them. Only eight of the twelve made it back to Zanzibar in October ’66. The halvidar stayed with the expedition but died of dysentery in September ’66.

Livingstone reached Zanzibar and was there for fifty days complaining of the filth, the stench and the horrors of the slave market. On the day he visited the market there were three hundred slaves for sale and he could tell from their looks and tribal tattoos that many came from the country around Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) and the Shire River.

He purchased equipment and provisions for his expedition, completed the training of the Nasik Boys and recruited ten “Johanna” men from Anjouan Island in the Comoros Archipelago including Musa who had been a sailor on the Lady Nyassa.

On 19th March 1866 the expedition left Zanzibar in HMS Penguin towing a dhow filled with a menagerie that a traveling circus might have been proud of: four buffaloes including a calf, six camels, two mules, four donkeys and two dogs.

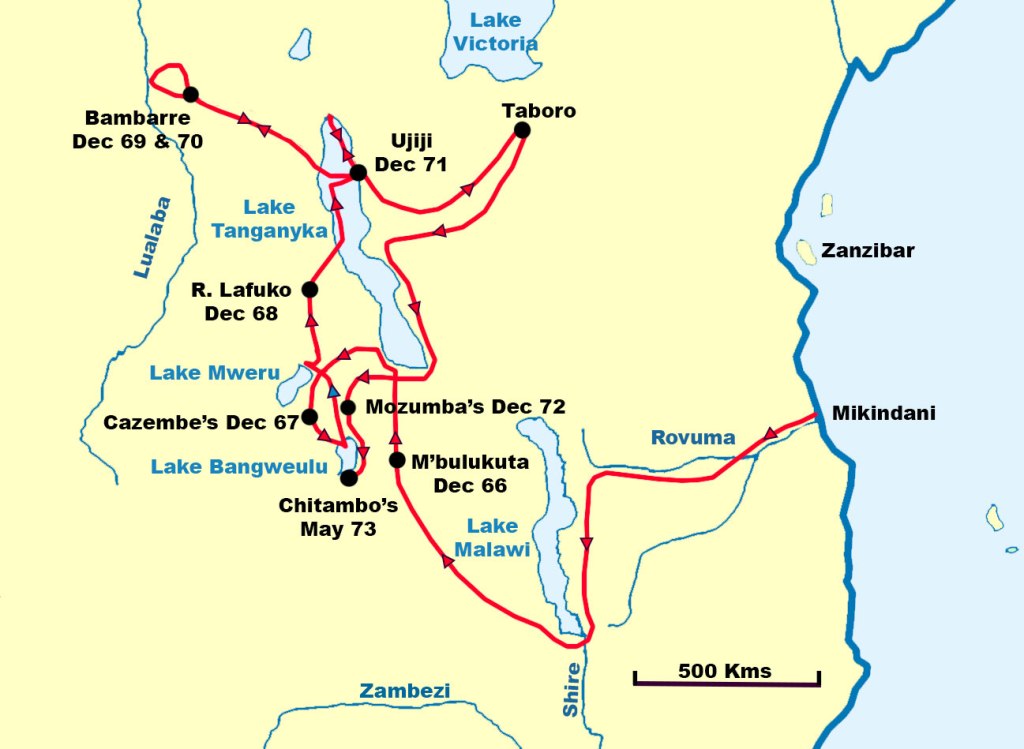

They landed at Mikindani 50 kms north of the Rovuma River in southern Tanzania.

The Fate of the Nasik Boys

For the names of the Nasik Boys I have used Donald Simpson’s list. Mr Simpson has established this group from several, often contradictory, sources.17

Richard Isenberg died at “Hassané or Pachassané” on the Rovuma River on around 18th June 1866. He was the first of the Nasik Boys to die. He had fallen behind on the 4th June with Abraham Pereira, Simon Price and a number of the sepoys and never caught up.

On the 7th June Abraham came up and told Livingstone that Richard was weak so he “sent off three boys with cordials to help him on” but on the 18th June when Simon, Rueben and Mabruki caught up with the expedition they brought the news that Richard had died.

Albert Baraka appears representative of how Livingstone viewed the Nasik Boys. Throughout his journals he complains of their laziness and their tendency to be led astray by the sepoys. Baraka had refused to work on May 9th and Livingstone had beaten him.

Baraka appears to redeem himself as by January 1867 he is responsible for carrying the medicine box:

This was done, because with the medicine-chest were packed five large cloths and all Baraka’s clothing and beads, of which he was very careful.”18

Unfortunately Baraka is tricked by two runaway Yao slaves who had been traveling with the party since early December. He gives them his load whilst he goes off to collect mushrooms and, in dense forest, the Yao take the opportunity to run off with the medicine chest and a number of other items. Livingstone records that they:

“…took all the dishes, a large box of powder, the flour we had purchased dearly ……., the tools, two guns, and a cartridge-pouch; but the medicine chest was the sorest loss of all! I felt as if I had now received the sentence of death.”

“Losing the precious quinine and other remedies” was a major loss and most probably had a long-term impact on Livingstone’s health and the expedition in general. Livingstone never forgave Baraka.

When the expedition leaves Lake Tanganyika in May 1867 Baraka returns to Ponda, Tippu Tip’s village, with the intention of making his way back to Zanzibar.

Abraham Pereira, who had been trained as a blacksmith at Sharanpur is mentioned as a hard worker. When they reach Mataka’s on the western shore of Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) he recognises an Uncle in the crowd and learns that his mother and two sisters were sold into slavery soon after he was taken. The uncle and Mataka are keen that he stays with them but he decides to continue with the expedition.

He is one of the four who travelled with Livingstone when he headed for Lake Bangweolo in April ’68 and acted as a messenger to the powerful Chief or King Casembe but he refused to go and look for the Lualaba River in June ’70.

Abraham tried to rejoin the expedition at the end of 1870 but Livingstone saw him as a ring leader of the “deserters” and refused. He was later reported by Ferrar to be living at Unyanyembe (Tabora).

Simon Price was another of the four who travelled with Livingstone when he headed for Lake Bangweolo in April ’68 but refused to go and look for the Lualaba River in June ’70. Livingstone saw him as the other ringleader and never allowed him to rejoin the expedition. He initially stayed in Bambarre with Abraham and some women whose husbands were away engaged in the ivory trade.

He tried and failed to obtain a wife and protection from Swahili traders and later followed Livingstone in an attempt to be reemployed but Livingstone sent him away. He was later reported by Ferrar to be a trader working between the coast and the interior.

James Rutton is mentioned very occasionally, and very much in passing, in Waller’s account of Livingstone’s last expedition. He refused to go to Lake Bangweulu in April ’68 and to the Lualaba River in June ’70 but rejoined the expedition later.

He was killed by an arrow on 4th February 1871 and according to some accounts was eaten by the Manama.19

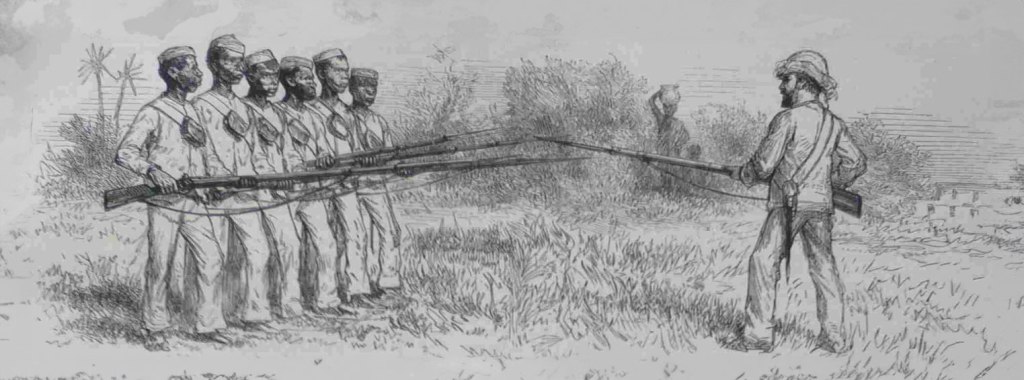

Image Harrison Collection © Scarborough Museums and Galleries20

Andrew Powell was beaten by Livingstone on 4th September 1866 for complaining that his load was too heavy. He left the expedition immediately after this incident to live at Mataka’s where, according to the Doctor, he would be well fed and not have to work.

Reuben Smith also left the expedition at Mataka’s but joined the sepoys who had deserted around this time and travelled with them to the coast and eventually to Zanzibar which he reached in October 1866. Ferrar says he became ill and was sent back to Bombay.21

Nathaniel Cumba Mabruki is one of the four who travelled with Livingstone when he headed for Lake Bangweolo in April ’68 but refused to go and look for the Lualaba River in June ’70. He eventually rejoined the expedition sometime in 1870 and was mentioned by Stanley as doing a good job looking after Livingstone’s house in Ujiji while Stanley and Livingstone explored Lake Tanganiyka.

In August 1871, having been unwell for some time, Mabruki left the expedition at Tabora. As seems to be the case when someone leaves him Livingstone has nothing good to say about a boy who had followed him for one month short of six years – “Very lazy”.22

Ferrar said he followed Livingstone’s body to Zanzibar so he must have rejoined the expedition at some point.

Edward Gardner was one of the five loyal men and the only Nasik Boy who was still with Livingstone when Stanley found him in December 1871. He was one of the four who travelled with Livingstone when he headed for Lake Bangweolo in April ’68 and was the only Nasik Boy who went with him to find the Lualaba in June ’70.

When they returned to Bambarre after failing to reach the Lualaba Gardner joined some Swahili men on a raid, possibly whilst drunk, and returned with a woman he had captured.

He stayed with Livingstone to the very end and was part of the caravan that carried his body to the coast. He was the only Nasik boy who never deserted the doctor and was the most loyal follower despite being one of least well known.

In 1874 he was recruited in Zanzibar by Henry Morton Stanley who was embarking on an expedition to survey Lake Victoria and to determine the course of the Lualaba and Congo rivers as part of the ongoing quest to establish the source of the Nile.

On February 4th 1875, north of the Manonga River in Tanzania en route to Lake Victoria:

“Gardner, one of the faithful followers of Livingstone during his last journey, succumbed to a severe attack of typhoid fever. We conveyed the body to camp, and having buried him, raised a cairn of stones over his grave at the junction of two roads, one leading to Usiha, the other to Ivamba. His last words were, “ I know I am dying. Let my money (370 dollars), which is in charge of Tarya Topan of Zanzibar, be divided. Let a half be given to my friend Chumah, and a half be given to these my friends — pointing to the Wangwana — that they may make the mourning-feast.” In honour of this faithful, the camp is called after his name “ Camp Gardner.” 23

The Boys Rescued at M’bame’s in 1861

In 1861 David Livingstone had led Bishop Mackenzie and his missionaries through the Shire Highlands in Malawi.

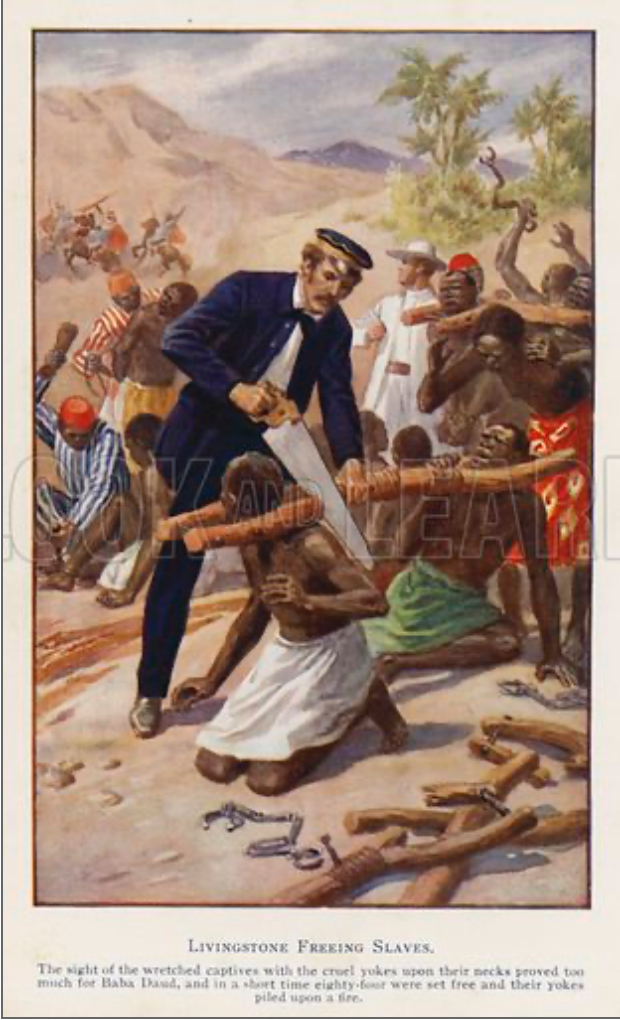

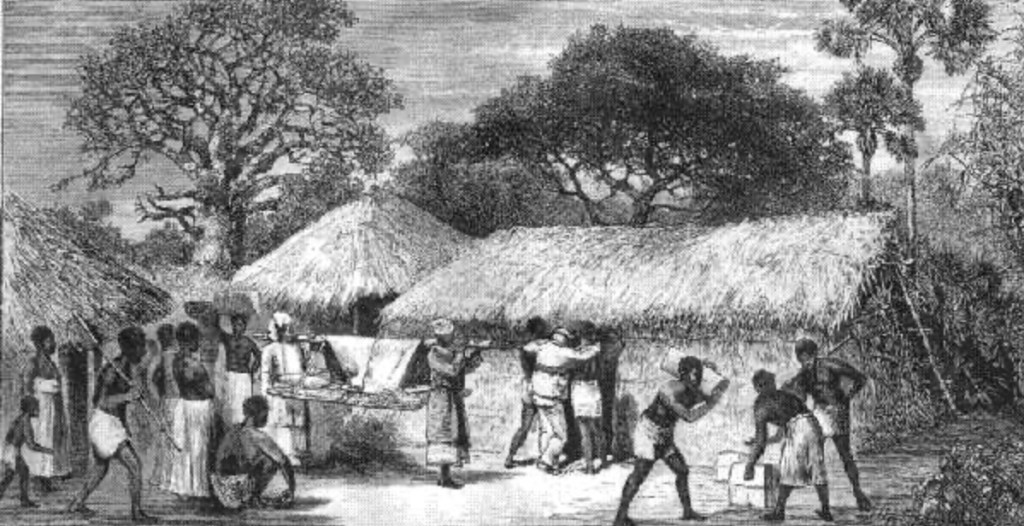

They encountered a slave caravan at Mbame’s, where the Blantyre Mission Church stands today, and Livingstone intervened to free the enslaved people.

The slavers ran off when confronted and the Europeans cut the cords that restrained the women and sawed off the six-foot-long, forked, slave sticks that shackled the men.

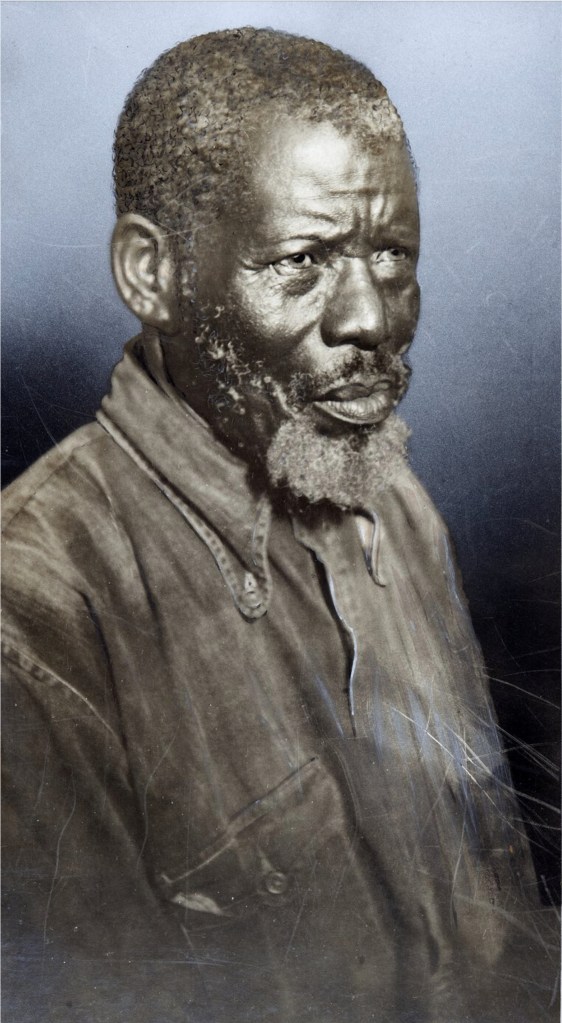

Among the slaves liberated that day were two eleven-year-olds, Chuma and Wekatani. Chuma was togo on to become one of the best known of all the liberated East African slaves and one of the greatest black explorers, perhaps second only to Sidi Mubarak Bombay.

James Chuma, The Early Years

Chuma was a Yao, the son of Chimilengo, a fisherman, and his wife Chinjeriapi who lived in Kusogwe. He had been taken as a slave and sold to a Portuguese slaver. 25

When he was at the Magomero mission he had been Henry Rowley’s servant. Rowley who spells Chuma’s name as “Juma” records one anecdote about the boy.

One evening my boy Juma came into my hut with his supper, a lump of Nsima, and something which looked like a burnt sausage.

‘What is that, Juma?’ said I.

‘Bewa,’ said he.

‘Is it good ?’

‘It is good. Better than sheep, better than goat, better than bird or fish, better than all other meat. Shall I roast one for you ? ‘

And he pulled out a fine rat from his bag, and held it up for admiration. I nodded assent, and off he ran delighted. He returned with the rat frizzled and black, cooked to a turn. Its odour was savoury — but it was rat, and I hesitated.

‘Did you skin it, Juma ?

‘No ! ‘

‘Did you take the entrails out, Juma ?

‘No ! They are the best of it — the fattest !’ 26

After the demise of the mission at Magomero and Bishop Tozer’s abortive attempt to establish a new mission on the mainland the UMCA withdrew to Zanzibar in 1864 (see here).

Livingstone took Chuma and Wekatani in the Lady Nyassa from the Zambezi River to Bombay on an epic voyage of 2,500 miles, lasting forty-four days.

Once in Bombay Chuma and Wekatani were boarded with a Christian family and enrolled at John Wilson’s Free Church College.

When he was back in Bombay in 1865 Livingstone collected Chuma and Wekatani from Dr Wilson (see right) and learned they had done well at school.

They asked to be baptised, and were Christened as James Chuma and John Wekatani on 10th December 1865.

Wekatani’s Story

Wekatani, the second boy rescued from the slavers near Mbame’s village, had, according to the good Doctor, “excessive levity”. In September 1866 near Cape Maclear in Malawi Wekatani met a brother and discovered his father, who had sold him into slavery, was dead and that he had brothers and sisters living on the shores of Lake Palombe (Lake Malombe).

He asked to be released to return to his original village. Livingstone did little to persuade him to stay, gave him a flint-gun, a length of cloth and some paper and left him to wait for his relatives to collect him from Mponda’s. The boy, who was Bishop Mackenzie’s favourite, faded from history 27 for ten years.

Edward Daniel Young, better known as E.D.Young, was in the process of establishing the Livingstonia Mission on Lake Nyasa (lake Malawi) when he met Wekatani at Mponda’s in October 1875.

During 1876 Wekatani helped Young as an interpreter and provided intelligence about the country. He was on the steamer Ilala when she first sailed on the lake. He remembered hymns and prayers from his time at Magomero.

James Chuma and the 1866 Expedition

1866 to 1871

Livingstone planned to train the two, now, fourteen or fifteen year old boys as servants but once the expedition set off from Mikindani he found they were rather too frivolous, boisterous and careless with his possessions; he handed them over to Simon Price, one of the Nasik Boys to be trained as cooks.

He described James Chuma as a lively boy who frequently provoked laughter but also read frequently. Livingstone believed:

“If I had the means of educating him I would prefer him to all the others.” 28

Not surprisingly, Chuma appeared to have forgotten his life before being liberated and had developed the idea that, in his homeland, the Mang’anja sold their people into slavery whereas the Yao, the group to which he belonged, did not. Chuma was probably sold into slavery by his own relatives, a common occurrence in those troubled times, and Livingstone was surprised that he gave gifts to a women they meet west of Cape Maclear who pretended to be an aunt.

“Chuma, for instance, believes now that he was caught and sold by the Manganja, and not by his own Waiyau [Yao], though it was just in the opposite way that he became a slave, and he asserted and believes that no Waiyau ever sold his own child. When reminded that Wikatani was sold by his own father, he denied it;”

In early 1867 the expedition marched through the rainy season from M’bulukuta’s to the southern tip of Lake Tanganyika; everyone was exhausted, they had struggled to find porters and as a consequence were overloaded, they had lost their medicine chest and were rapidly running short of food. Chuma had been caught secretly eating from a bag of flour he had hidden and the morale of African expedition members was falling.

By the time they reached the lake in April Livingstone, Simon Price and Chuma were all ill and Livingstone, when well enough to write, was complaining of people’s laziness.

In mid-May the expedition fell in with an Arab caravan with whom they traveled for the next eleven months. This strange relationship with slavers, which is to be repeated later, perhaps speaks to Livingstone’s frequent bouts of illness, his general fatigue and a sense that he is losing control of his followers.

He blames the Arabs for corrupting the young men of his party and, when he decides to strike out for Lake Bangweolo (Lake Bangweulu) from Kabwabwata the following April and away from the Arabs, Chuma is one of many who are happier to stay behind enjoying the pleasures of female company and bange (cannabis).

“The fact is they are all tired and ……… give themselves over to bange and black concubines, they would like to remain here and (for me to) pay them for smoking the bange; and deck their prostitutes with the beads which I gave them regularly for food.”

Chuma and the others had given the excuse that Cazembe (see right32) would kill them if they passed through his territory but when Livingstone reached Cazembe’s village he proved to be friendly and he stayed there for four months.

“Cazembe is a most intelligent prince; he is a tall, stalwart man, who wears a peculiar kind of dress, made of crimson print, in the form of a prodigious kilt. In this state dress, King Cazembe received Dr. Livingstone, surrounded by his chiefs and body-guards“

“Cazembe gave orders to let the white man go where he would through his country undisturbed and unmolested. He was the first Englishman he had seen, he said, and he liked him“

“Shortly after his introduction to the King, the Queen entered the large house surrounded by a body-guard of Amazons with spears (right 33).

She was a fine, tall, handsome young woman, and evidently thought she was about to make an impression upon the rustic white man, for she had clothed herself after a most royal fashion, and was armed with a ponderous spear” 34

Initially when he returned from Bangweolo he refused to allow Chuma to rejoin the expedition. He is resentful that the boy he had rescued from slavery, fed, clothed and educated had been disloyal and overcome by “bange and black women”. He was later to tell Stanley that Chuma repented.

By the end of 1870 the expedition was in very poor shape and in desperate need of resupply; of the thirty-seven men and thirteen animals who had landed at Mikindani in March 1866 just nine men and no animals were left.

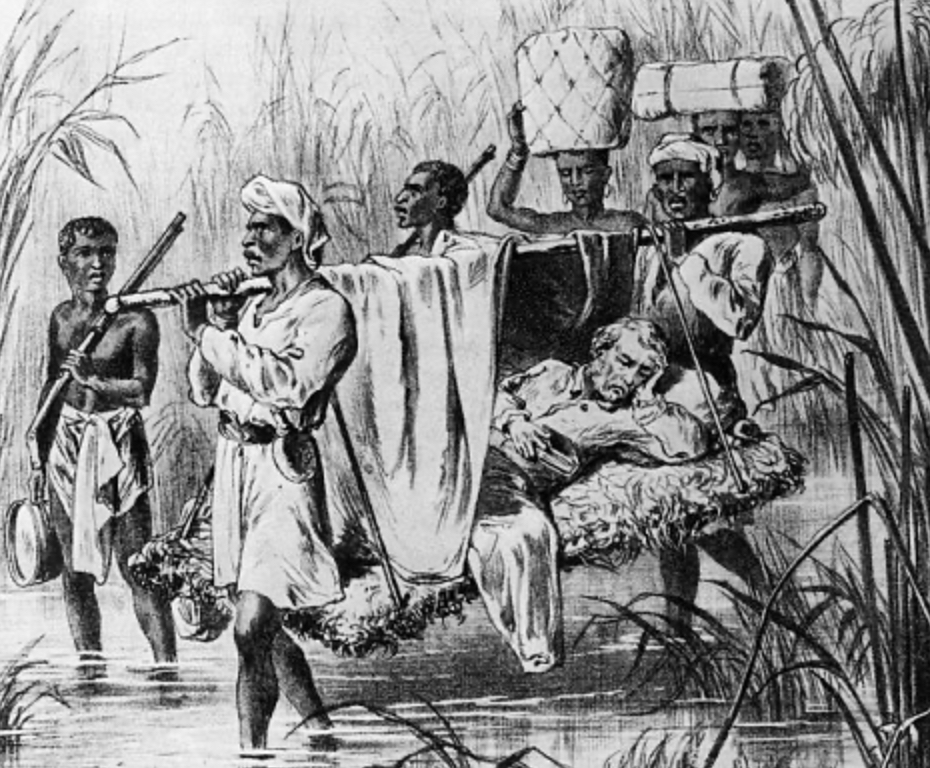

They set out from near the Lualaba River for Ujiji on the east coast of Lake Tanganyika. Livingstone was seriously ill and had to be carried part of the way.

“I am so weak I can scarcely speak. …….. This is the first time in my life I have been carried in illness, but I cannot raise myself to the sitting posture. No food except a little gruel.

They reached Ujiji on 23rd October 1871 expecting to find the fresh equipment and supplies that had been arranged to arrive there in batches. Chuma and Susi went to see their agent, Sherif, to collect their supplies but when they return they are in tears and told Livingstone:

“All our things are sold, sir; Sherif has sold everything for ivory.” 35

Livingstone was despondent and he and his little band could only expect to rely on the goodwill of the Arab traders at Ujiji until a message could be sent to the coast and supplies sent back. A round trip of many months.

“But when my spirits were at their lowest ebb, the good Samaritan was close at hand, for one morning Susi came running at the top of his speed and gasped out, ‘An Englishman ! I see him’ and off he darted to meet him.

The American flag at the head of a caravan told of the nationality of the stranger. Bales of goods, baths of tin, huge kettles, cooking pots, tents, &c., made me think ‘ This must be a luxurious traveller, and not one at his wits’ end like me.’ (28th October)

It was Henry Moreland (sic) Stanley, the travelling correspondent of the New York Herald.” 36

The Five Faithfuls

When Stanley arrives at the head of his column he finds that Livingstone’s expedition comprises just six people including the Doctor. Stanley listed their names because he believes “these faithful people should not be forgotten” 37:

- Susi (chief and confidential servant) [Abdullah Susi]

- Chumah (second leader) from Nassick School [James Chuma]

- Hamoydah, released from slavery on the Zambezi [Amoda]

- Edward Gardner, from Nassick School

- Halimah, cook, and wife of Hamoydah [Amoda’s wife]

Abdullah Susi is sometimes referred to as a freed slave but I have found no evidence to support this idea. When he, and Amoda, first met Livingstone in August 1858 they were employed by Major Tito Sicard, the Commandant of Tete, who was then stationed in Shupanga on the Zambezi river. Livingstone employed them as woodcutters either in ’58 or later.

Abdullah Susi Adrian S. Wisnicki38

He is frequently mentioned in Livingstone’s journals and was probably the most “senior” of the Africans. Johnston and Thomson considered taking him on their 1876 expedition to Lakes Nyasa and Tanganyika but:

“On inquiry we found that Susi had fallen into very bad drinking habits, and was in a state of destitution through his debaucheries. He was, perhaps, even a more able man than Chuma in some respects, and but for his prominent failing, he might have been at least equally successful. He was very desirous of joining our caravan, but, considering that he had always been rather above than under Chuma in his previous engagements, we thought it would not be prudent to have them both, and so declined his services.” 39

Abdullah Susi was with Stanley and helped to establish Leopoldville in 1881. Between 1883 and 1891 he worked for the UMCA as a caravan leader. He was baptised in Christ Church, Zanzibar, as David in 1886 and died in 1891.

Hamoydah Amoda was also on the Zambezi expedition and employed to cut wood for the Pioneer. According to Livingstone’s last journals Amoda absconded from the last expedition in April 1868 but Stanley lists him as being with Livingstone when he famously finds him in 1871 and other sources confirm that five companions stayed with the Doctor after his other porters had become demoralised and left him in ’68.

Image: Pilkington-Jackson, “Last Journey,” 1929.40

Amoda was with Stanley on his 1874 expedition to Lake Victoria and was a crew chief on the Lady Alice which the expedition carried in sections from the coast to sail on Lake Victoria. He died in Uganda in 1876.

Stanley & Livingstone

Viewed from the roof of our tembé. 41

Stanley and Livingstone spend “many happy days” at Ujiji, feeding the doctor four meals a day and chatting about African travel. Stanley gives a colourful description of the market at Ujiji where Chuma and his companions must have wandered or shopped every day. The description dispels any notion that the Expedition was lost in “darkest Africa”.

“The market-place overlooking the broad silver water afforded us amusement and instruction. Representatives of most of the tribes dwelling near the lake were daily found there.

There were the agricultural and pastoral Wajiji, with their flocks and herds; there were the fishermen from Ukaranga and Kaole, from beyond Bangwe, and even from Urundi, with their whitebait, which they called dogara, the silurus, the perch, and other fish; there were the palm-oil merchants, principally from Ujiji and Urundi, with great five-gallon pots full of reddish oil, of the consistency of butter; there were the salt merchants from the salt-plains of Uvinza and Uhha; there were the ivory merchants from Uvira and Usowa; there were the canoe-makers from Ugoma and Urundi; there were the cheap-Jack pedlers from Zanzibar, selling flimsy prints, and brokers exchanging blue mutunda beads for sami-sami, and sungomazzi, and sofi.

The sofi beads are like pieces of thick clay-pipe stem about half an inch long, and are in great demand here. Here were found Waguhha, Wamanyuema, Wagoma, Wavira, Wasige, Warundi, Wajiji, Waha, Wavinza, Wasowa, Wangwana, Wakawendi, Arabs, and Wasawahili, engaged in noisy chaffer and barter. Bareheaded, and almost bare bodied, the youths made love to the dark-skinned and woolly-headed Phyllises, who knew not how to blush at the ardent gaze of love, as their white sisters; old matrons gossiped, as the old women do everywhere; the children played, and laughed, and struggled, as children of our own lands; and the old men, leaning on their spears or bows, were just as garrulous in the Place do Ujiji as aged elders in other climes.”

In mid-November 1871 Livingstone and Stanley head off together with “Stanley’s men” to explore Lake Tanganyika returning to Ujiji on 13th December. Chuma was on this trip and was with the doctor when tension arose near Cape Luvumba between the local people and Stanley’s entourage because the villages mistook them for Arabs. The doctor defuses the situation by showing he is a white man and not an Arab or a Swahili.

On 14th March 1872 Stanley leaves Livingstone and his African companions at Unyanyembe (Tabora) and heads to the coast. Susi and Chuma insist on shaking his hand.

The little band settle down in Unyanyembe and watch the comings and goings of the Arab trading post, occasionally visiting chiefs and villages in the area. Livingstone is philosophical during the five months they wait for Stanley’s relief column to reach them. When writing advice to other explorers it seems he is thinking of the Nasik boys when he writes:

“Educated free blacks from a distance are to be avoided: they are expensive, and are too much of gentlemen for your work. You may in a few months raise natives who will teach reading to others better than they can, and teach you also much that the liberated never know. A cloth and some beads occasionally will satisfy them, while neither the food, the wages, nor the work will please those who, being brought from a distance naturally consider themselves missionaries.”

In June 1872, N’taoéka, “a fine-looking women” has attached herself to the group rather than to one of the three single men. Livingstone sees her as a potential problem and suggests she marries one of Chuma, Gardner or Mabruki. She initially laughs at the idea but is eventually persuaded to marry Chuma who promises to reform his laziness which he explains is caused by not having a wife.

The above image is of a unknown Tanganyikan Women43

The Relief Column

In February 1872 William Salter Price at the “Nasik” School in Sharanpur began talking to the boys about an expedition to find Livingstone. A number of boys were keen to go and five were selected.

The six new Nasik Boys:

Matthew Wellington survived the expedition and returned with the body to Zanzibar.

He was sent to the CMS Mission at Mombassa, and according to the journals of the Rev. W.S. Price, was awarded with a Royal Geographical Society (RGS) medal by Major Evan-Smith on 24th September 1875 as one of the faithful followers of Dr. Livingstone.

He died in 1935 and was the last living link with Livingstone.

Jacob Wainwright who was the most literate of the group and read the service when they buried Livingstone’s heart, returned with the body and travelled with his body to London.

Carris Ferrar who wrote, or more probably dictated, his own account of the last journey of Livingstone. 44 Once the body reached Zanzibar he was paid off by the Consul and sent to “Mombas” (The CMS Mission at Mombassa).

According to the journals of the Rev. W.S. Price, he was awarded with a RGS medal by Major Evan-Smith on 24th September 1875 as one of five faithful followers of Dr. Livingstone.

He was not happy in Mombassa and signed to HMS Daphne, probably as a servant to the Engineer. He was discharged as “unfit for duty” in Aden. He returned to Bombay, arriving in July 1874.

He later went back to the Mission at Frere Town, Mombassa; in 1875 the Rev. Price’s wife overheard him praying and towards the end of 1876 he was running the shop at the mission along with Matthew Wellington. In 1888 he was in charge of the settlement for freed slave boys at Shimba south-west of Mombassa.

John Wainwright was lost south of Lake Tanganyika before the caravan carrying Livingstone’s body reached Chitimbwa in August or September 1873. Chuma reported that he had fallen behind and never caught up; Matthew Wellingston said he died from “fever and dysentery”.

Richard Rutton and Benjamin Rutton both survived the expedition and returned with the body to Zanzibar. They appear to have been sent to the CMS Mission at Mombassa, and according to the journals of the Rev. W.S. Price, were each awarded with a RGS medal by Major Evan-Smith on 24th September 1875 as one of five faithful followers of Dr. Livingstone.

On their arrival at Zanzibar in 1872 the Nasik Boys were placed in accommodation organised by Dr. Kirk, the consul, while the rest of the expedition was formed.

It is interesting that, according to Ferrar, the new expedition was originally formed to find Livingstone but when they arrived at Buagomayo (Bagamoyo) on the coast they met Stanley returning from the interior with the news that Livingstone had been found and was alive. Leaving some men to guard their equipment they returned to Zanzibar with Stanley.

When he reached Zanzibar in May 1872 Henry Morton Stanley wrote that he had:

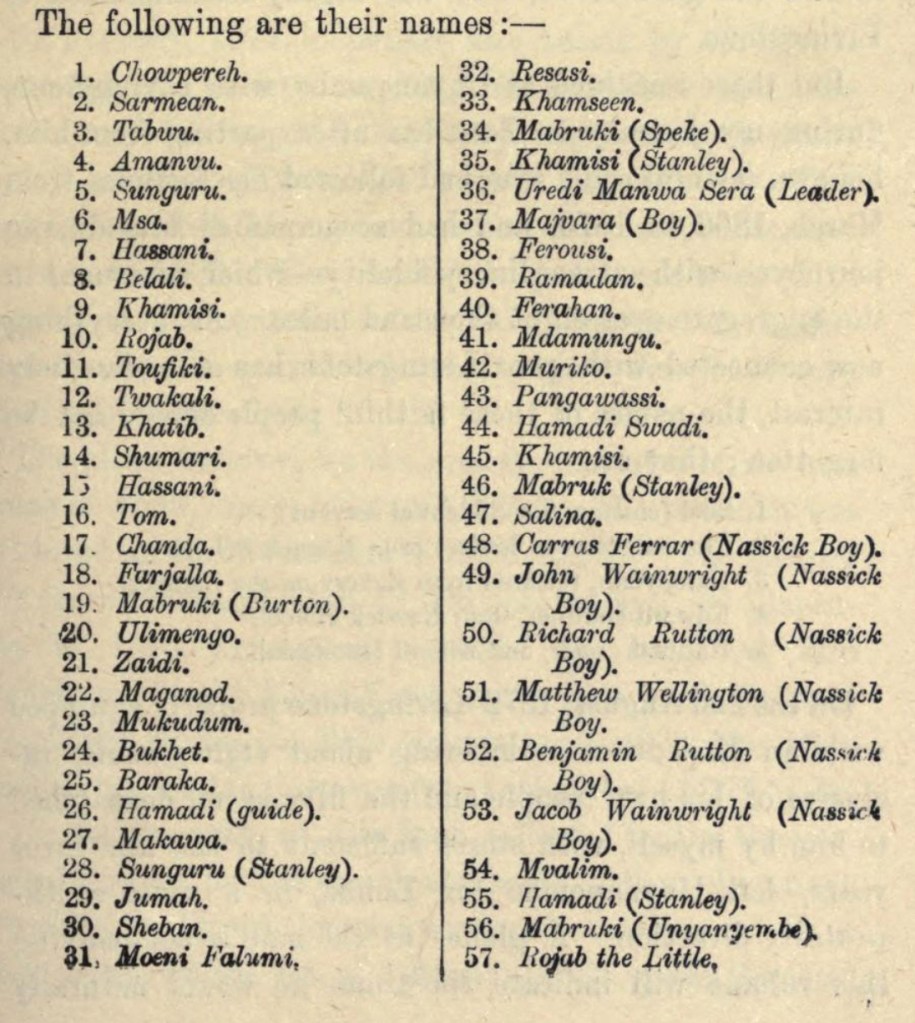

“despatched to Dr. Livingstone as per (his) request a force of fifty-seven men, who were destined to convey his supplies from Unyanyembe westward until he should have resolved the problem to his satisfaction whether the Lualaba was the Nile River or the Congo.” 45

From How I Found Livingstone by Henry Stanley

Stanley listed the names of all fifty-seven men in his famous bestseller “How I found Livingstone” 46. These men not only traveled back to resupply Livingstone at Unyanyembe they became his new expedition force as he pursued his obsession to find the source of the Nile.

They reached Unyanyembe 14th August 1872 having taken seventy-four days to march from the coast. Livingstone still has reservations regarding the Nasik Boys and asks them if they want to travel with him or return to the coast.

The new Nasik Boys decide:

“We would go and be faithful to him in all the trials and enormous difficulties and countless privations while journeying about through countries unknown to finish his work assigned to him.” 47

Livingstone is now ready to go exploring again but he is a weakened man. He admits in a letter to Horace Waller that he has lost all or most of his teeth, he has had numerous attacks of malaria and Stanley writes that he regularly suffers from dysentery. He is more dependent than ever on his loyal African companions.

The Search for the Nile Resumes

On August 25th 1872 they set off again. The Nasik Boys quickly disappoint their master yet again when they lose two of the caravan’s cows, including the best milker. Susi was instructed to give the two boys responsible a beating.

By the middle of October they reached the shores of Lake Tanganyika, everyone is tired, many of the party are ill and a few have drifted away. Livingstone is suffering badly from dysentery and is often unable to eat for many days on end.

By the middle of November many of the cows and donkeys they brought from Unyanyembe had been slaughtered for food or succumbed to the tsetse fly. The rains were beginning, their own food supply had been severely depleted and villagers had little or no food they were willing to sell.

With the rainy season well advanced they were frequently crossing swollen streams and rivers, sometimes three or more in a single day, and increasingly the doctor was too weak to wade and had to be carried on his companions’ shoulders.

“His men speak of the march from this point as one continual plunge in and out of morass, and through rivers which were only distinguishable from the surrounding waters by their deep currents and the necessity for using canoes. To a man reduced in strength, and chronically affected with dysenteric symptoms ever likely to be aggravated by exposure, the effect may be well conceived !” 49

A typical entry in Livingstone’s journal describes the challenge of marching in central Africa in the rainy season:

“After an hour we crossed the rivulet and sponge of Nkulumuna, one hundred feet of rivulet and two hundred yards of flood, besides some two hundred yards of sponge, full, and running off; we then, after another hour, crossed the large rivulet Lopopussi by a bridge which was forty-five feet long, and showed the deep water; then one hundred yards of flood thigh-deep, and two or three hundred yards of sponge. After this we crossed two rills, called Linkanda, and their sponges, the rills in flood ten or twelve feet broad and thigh-deep.”

As the sodden expedition dragged itself into 1873, Chipangawazi, one of the men in the caravan dies, one of the women is too ill to walk and their last cow dies. His obsession was beginning to resemble a death wish and although in his day he was eulogised for his willpower to a more modern eye it increasingly looks obsessive, egotistical and reckless.

He notes in his journal that he is constantly loosing blood as a result of haemorrhoids and is suffering from acute stomach pains. He is now sixty years old and has spent most of the previous thirty years wandering through tropical Africa. He perhaps senses the end is near when he writes:

“If the good Lord gives me favor, and permits me to finish my work, I shall thank and bless him, though it has cost me untold toil, pain, and travel. This trip has made my hair all gray.”

They reached Lake Bangweulu on February 13th. Susi and Chuma, who have not been mentioned since they left Unyanyembe, find canoes to take them across to Nsumbu island where they camp near Matipa’s village.

They continue to walk, or wade, around the flooded plain that surrounds the eastern shores of Bangweulu using canoes to move some of the party and their equipment. Chuma, along with Susi, is used as a messenger, or more likely a negotiator and he often travels ahead of the main party.

By mid-April Livingstone is struggling to keep his journal up-to-date and his entries are sketchy and often hardly legible. Chuma and Susi tell Waller of his attempt to travel on April 21st:

“This morning the doctor tried if he were strong enough to ride on the donkey, but he had only gone a short distance when he fell to the ground utterly exhausted and faint. Susi immediately undid his belt and pistol, and picked up his cap, which had dropped off, while Chuma threw down his gun and ran to stop the men on ahead.

When he got back, the doctor said, “Chuma, I have lost so much blood, there is no more strength left in my legs: you must carry me.” He was then assisted gently to his shoulders, and, holding the man’s head to steady himself, was borne back to the village and placed in the hut he had so recently left.”

On April 22nd his companions make him a bed suspended from a pole that can be carried by two people, a “kitanda”; Chowpéré, Songolo, Chuma, Soiwféré and Adiamberi take turns with the pole on their shoulders and the caravan trudges on for the next few days. On the 26th Livingstone asks Susi to count how many bags of beads they have and to trade with them for ivory which he suggest they should carry to Ujiji to trade for cloth that, in turn can be traded for food as they march on to Zanzibar. It is clear that Livingstone does not expect to travel much further and is preparing his companions for their return journey.

They continue on around Lake Bangweulu, even though it is clear that Livingstone is dying, he is now permanently carried in the kitanda and when they rest it becomes his bed. He was in acute pain and Chuma has to gently help him in and out of the kitanda when he needed to relieve himself and he drifts in and out of consciousness. Susi goes ahead to build, what will be, his last hut, at Chitambo’s village.

On April 30th Chitambo visits him for a short time but he is too exhausted to talk. In the afternoon he asks Susi to bring him his watch so he can wind it and late evening, when the men are sitting round their fires, Susi is called to the doctor’s hut. He is asked how far it is to Luapula River, to which he replies “three days master”.

He is called a third time and instructed to boil some water so Livingstone can self administer some medicine. Susi hands him the cup of water and places the “calomel” by his bed.

At about 4 am on May 1st 1873 the Scottish adventurer, missionary, abolitionist, and explorer is found dead, kneeling by his bed, as if in prayer.

“It seems he literally bled to death. Although the exact cause is not known, it is possible that a combination of amoebic dysentery, bilharzia and the haemorrhoids that had afflicted him for many years ran their course.” 52

The Long Journey Home

Chuma, Susi, Amoda and Gardner have been with him, on this expedition, since he collected them from Bombay in 1865 and have been floundering in the swamps around Bangweulu for the last four months, often carrying their master. They are now 2,250 kilometres for the coast if they travel back via Unyanyembe (Tabora). They had travelled across central Africa for six long years and knew what covering such distances entailed.

Susi and Chuma call everyone together and, as the most experienced travellers, are voted to take command. They instruct the porters to open all of the doctor’s boxes and ask Jacob Wainwright to list the contents to ensure everything is accounted for and reaches the coast..

From this point forward when reading Livingstone’s last journals, perhaps, it is worth bearing in mind that it Chuma and Susi helped Waller document the narrative when they returned to England. Suffice to say they appear more frequently in Waller’s account than they do in Ferrar’s.

Led by two drummers Chitambo arrives, with a red cloth draped around his shoulders and his “chitenje” touching the ground.

With him are his wives and his all his people carrying bows, arrows and spears and, according to Ferrar, for the next two days:

“There was then the most devilish and fanatical morning (sic) dance in which men, women and children promiscuously mingled (while) the whole caravan knowing the great loss they had sustained fired incessantly their guns in honour of their master.“53

Once the “wake” was over the remnants of the expedition agree that the body must be taken back to the coast and Chuma visits Chitambo to seek permission to build a temporary village where they can prepare the body.

Chuma, Susi and Muanuaséré held a blanket over the heads of Farijala, one of the Swahili men, and Ferrar as they opened the body to remove the internal organs and to then fill the cadaver with salt and brandy.

Tonké, John Wainwright and Jacob Wainwright all stood around the enclosure and as Jacob had been asked to bring his Prayer-book perhaps he read from it during the procedure.

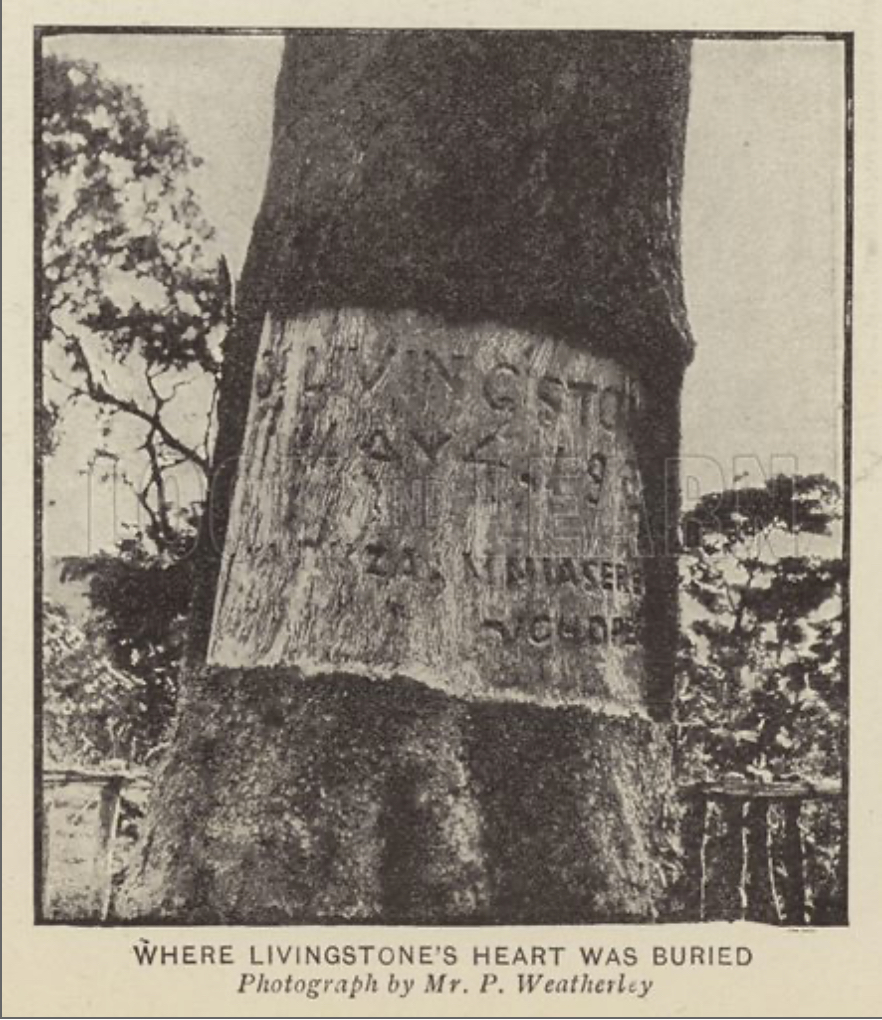

Jacob, the most literate of the group, is known to have read the burial service when they interred a box containing the internal organs and he carved a memorial on a nearby tree.

DR.LIVINGSTONE

MAY 4 1873

YAKUZA, MNIASERE

VCHOPERE

The body was then left in the sun for fifteen days.

When they eventually set off they headed west rather than fight back through the swamps to the east of Lake Bangweulu, however they only managed to march for two days before before having to stop at Muanamazungu’s because so many of the caravan was ill. Chuma had a severe pain in his groin and could not walk, Susi’s pains were in his legs, Songolo nearly died and two of the women, Kaniki and Bahati, did. This was a misogynistic age, there were probably a significant number of women and children in all of Livingstone’s caravans, camp followers as it were, but they are rarely mentioned by any of the black or white narrators.

It was more than a month before they resumed their march but at least the rainy season had finished. At N’kossu’s one of their number, Saféné, managed to shoot a villager when hunting but it is resolved by paying compensation to the chief.

Further on they find a large stockaded compound55 where a beer drinking party is in progress. They are refused entry but Saféné, Maunuaséré and Chuma force their way through the gate or over the stockade. Unsurprisingly they are fired at, by bow and arrow, by one of the drinkers and Sabouri is injured by a spear in the ensuing melee. The original inhabitants flee but soon return with reinforcements and Livingstone’s erstwhile followers not only defend themselves but assault and burn the surrounding compounds. They stay for a week and keep all the food and livestock they find as the spoils of war.

The caravan continues north towards Lake Tanganyika and past Lake Bangweulu they pick up the trail they made coming south. Before they reach Chitimbwa south west of Tanganyika the Nasik Boy John Wainwright is lost or dies of dysentery.

Arab traders tell them that the Doctor’s son is at Unyanyembe with a relief expedition. Jacob writes a letter explaining they have lost ten of their number, are hungry and out of powder for their guns.

Chuma goes ahead with the letter and reaches Unyanyembe on 20th October.

There he finds the relief expedition led by Lieutenant Verney Lovett Cameron RN (left) along with Dr. Dillon and Lt. Murphy.

Robert Moffat, Livingstone’s nephew, had been with them but had died of fever in May.

Chuma returned to his companions with supplies.

Livingstone’s body reaches Unyanyembe shortly afterwards and is met by two lines of red-coated, askaris commanded by Sidi Mubarak “Bombay”, another Bombay African but not from Sharanpur. Cameron continues into the interior but Murphy and Dillon join Livingstone’s followers and on November 9th they carry on to the coast. Just three days into the journey Dr. Dillon shot himself.

Chuma went ahead and reached Zanzibar on 3rd February 1874. Dr. John Kirk was on leave but Acting Consul Captain W.F. Prideaux sent Chuma back to the caravan with supplies.

Livingstone’s body and his papers and equipment eventually reached the coast at Buagamoyo to cries of “heria bahari” (welcome the sea). Lt. Murphy took the body to the French mission where it was placed in a coffin. Captain Prideaux crossed from Zanzibar and took the body back to the British Consulate.

Prideaux initially refused to pay James Chuma’s and Abdullah Susi’s passages to England with the coffin but subsequently relented and the two men eventually arrived in London in 1874.

They helped Horace Wallace write the account of Livingstone’s final expedition and were awarded a Royal Geographical Society silver medal by Major Prideaux on 17th August 1875.

In his address to the Society Sir Henry Battle Frere said of James Chuma:

“For eight long hazardous years he was the faithful servant of his liberator, and, when the spirit fled from that iron frame at last, it was Chumah, the liberated slave boy from the Shire Highlands, that led from Lobisa to Zanzibar those men who bore their dead master’s body, and to whom we are so much indebted for the safety of the Doctor’s journals and writings.” 56

Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

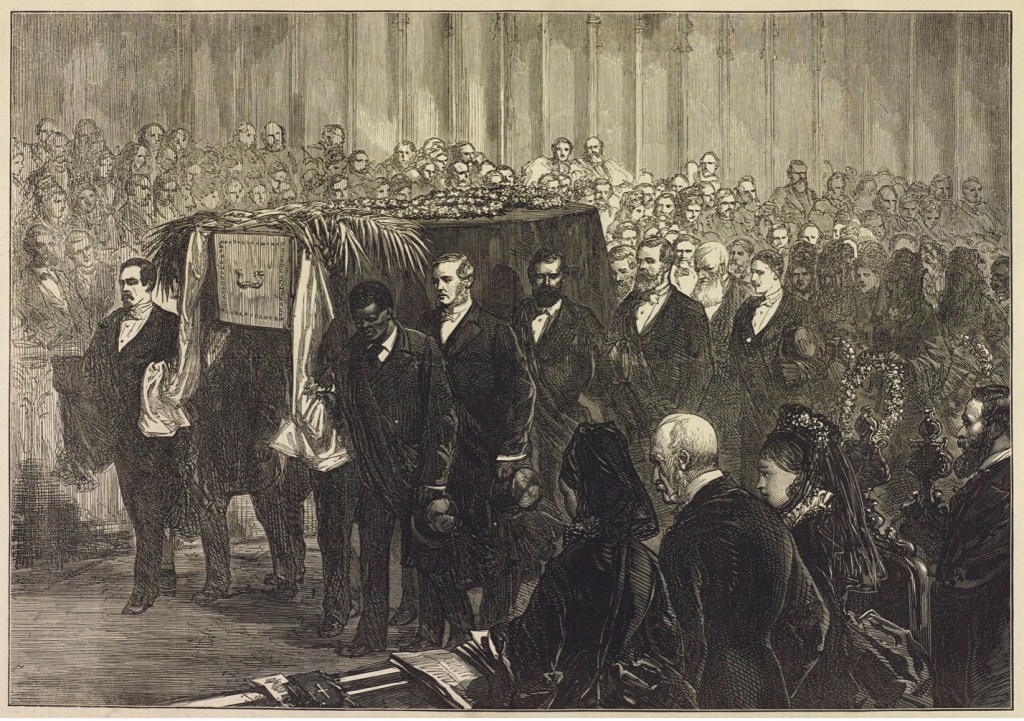

Jacob Wainwright and the Funeral

Jacob Wainwright was one of the Nasik boys who was with David Livingstone when he died at Chipundu and one of the men who helped carry his body to Bagamoyo from where it was shipped on to Zanzibar. Salter Price heard that Jacob was at Zanzibar with Livingstone’s body and telegraphed the CMS misson in Zanzibar to pay for him to be sent back to London with the body.

In London Jacob met CMS representatives and told the story of how he and his colleagues had found Livingstone but realising that, if they buried him and just carried word to Zanzibar, they might not be believed. They decided to carry the body, 2,250 kms to the coast.

One of the group knew a little about embalming and so they had prepared the body the best they could and buried his heart in a little grave. Jacob, being able to read, had taken Livingstone’s prayer book and read part of the burial service:

“And what did you do then, Jacob? ” asked Hutchinson. ” Sir,” was the reply, “we then sat down and cried.” 57

Copyright National Library of Scotland.58

On April 18th 1874 David Livingstone was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey in the presence of the great and the good of the British establishment, representatives of various churches and a black man, Jacob Wainwright, a Nasik boy, once a slave, rescued by the Royal Navy, educated by the Church Missionary Society in Sharanpur and once employed by Henry Stanley and David Livingstone.

Wood engraving by J. Nash.59

Jacob Wainwright returned to Zanzibar. In 1881 Joseph Thompson wrote of him:

“Jacob Wainwright we also found to have fallen considerably. After his return from England he got an excellent situation with some missionaries on the mainland, but became so impudent and forward that they were compelled to dismiss him.

He was in the habit of twitting his European masters with the fact that they had never, like him, had the honour of being presented to her Majesty Queen Victoria. His airs and arrogance in consequence of this honour became quite intolerable, and there was nothing for it but to part with him.

When last I heard of him he was acting as a door porter to one of the Zanzibar traders.” 60

Ndugu M’Hali “Kalulu”

The funeral was also attended by Kalulu or Ndugu M’Hali who was a liberated slave and the adopted son of Henry Stanley.

He was given to Stanley at Taboro during his expedition to find Livingstone.

He accompanied Stanley back to London spending eighteen months in an English private school.

Kalulu returned to Africa with Stanley and drowned in the Congo river in 1877.

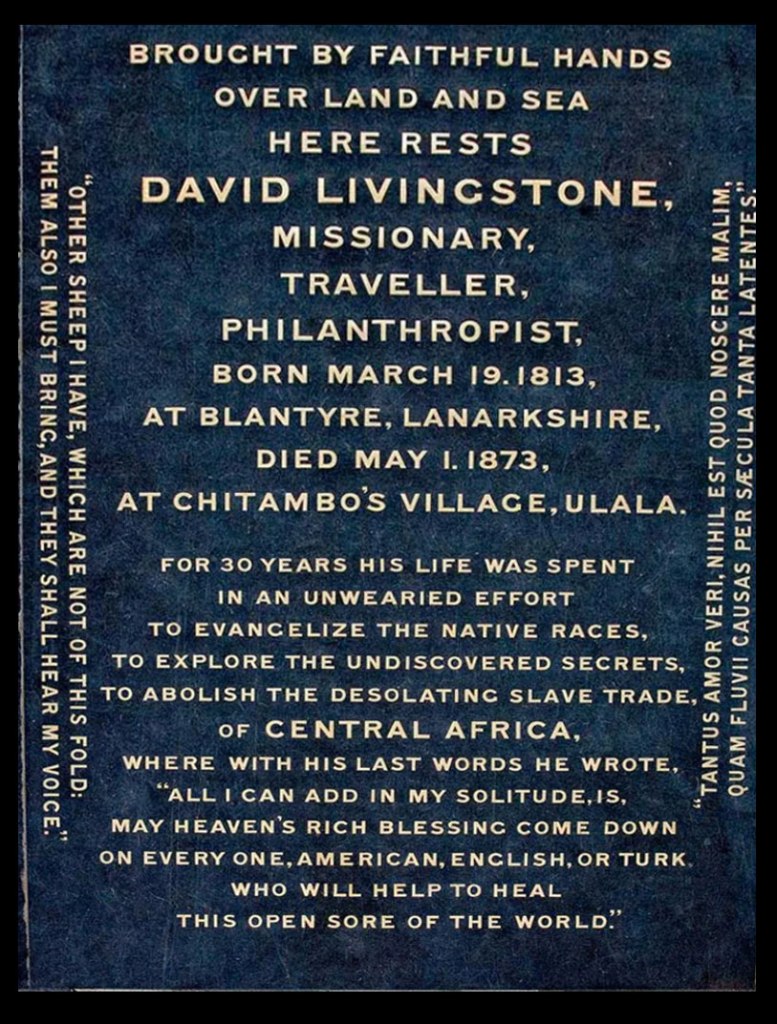

Faithful Hands Over Land and Sea

“Brought by faithful hands over land and sea, here rests David Livingstone.”

Caught up in the romantic notion that his African followers were so dedicated to a man who, from the perspective of the British public, was verging on a saint, they added these famous words to the memorial, as shown to the right above, in Westminster Abbey.

An apposite example of how the Victorians viewed and represented the Africans who accompanied the famous British explorers.

They romanticised the story of Livingstone being carried fourteen hundred miles from Chitambo’s to Bagamoyo but put no names or faces to the “faithful hands”.

The Faithful Hands

However, the Royal Geographical Society was more inclusive and cast sixty silver medals for the men who had accompanied Livingstone’s body on its last journey and survived.

They excluded Amoda’s wife and Livingstone’s cook, Halima; Major Euan Smith who presented the medals to those of the sixty who could be found in Zanzibar and Mombassa suggested that a spare medal should be presented to her but there is no record of whether this happened.

There and Back

The five Africans who started at Mikindani in 1866 and returned with the body in 1874 are:

- James Chuma – Freed Slave

- Abdulah Susi (Later christened David)

- Hamoydah Amoda

- Halima – DL’s Cook and Amoda’s Wife

- Edward Gardner – Freed Slave & Nasik Boy

Richard Isenberg and James Sutton, freed slaves and Nasik Boys are known to have died en route. John Wainwright, another freed slave and Nasik Boy was with the relief column and died on the journey carrying Livingstone’s body to the coast. Many other men and women died either on the original expedition or on the journey with the body to the coast. Few names are recorded but they include the Halvidar of the Sepoys.

The Other People on the Final Journey

There are fifty-seven other names of people who arrived back at the coast with the body. Fifty-six are from the RGS list of people awarded their commemorative medal and the other one is N’taéka, Chuma’s Wife, who definitely arrived back in Zanzibar where, along with Halima she had been sent some money. N’taéka died in 1880. There seems to be no trace of Halima after their return, although she is the heroine of the excellent novel “Out of Darkness, Shining Light” by Petina Gappah. 61

As mentioned before this is unlikely to be anywhere near a complete list as there would have been other women and children with the caravan. Jacob Wainwright and Waller mention other people dying during the march back but only give names to a few of the men and to none of deceased women. Given the horrendous conditions encountered on Livingstone’s last march and the return journey many children must also have died.

When the Victorian explorers are remembered the sacrifice made by dozens, if not hundreds of unrecorded Africans should not be ignored.

See Appendix A for those names we know.

James Chuma After 1875

James Chuma’s life after his return from London in 1875 will be covered in my next post.

Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Leave a reply to Mrinal Kulkarni Cancel reply