- Introduction

- Origins of African Slave Trade Routes

- What is Slavery?

- Do only Slave Societies Count?

- Modern Societies Dependent on Slaves

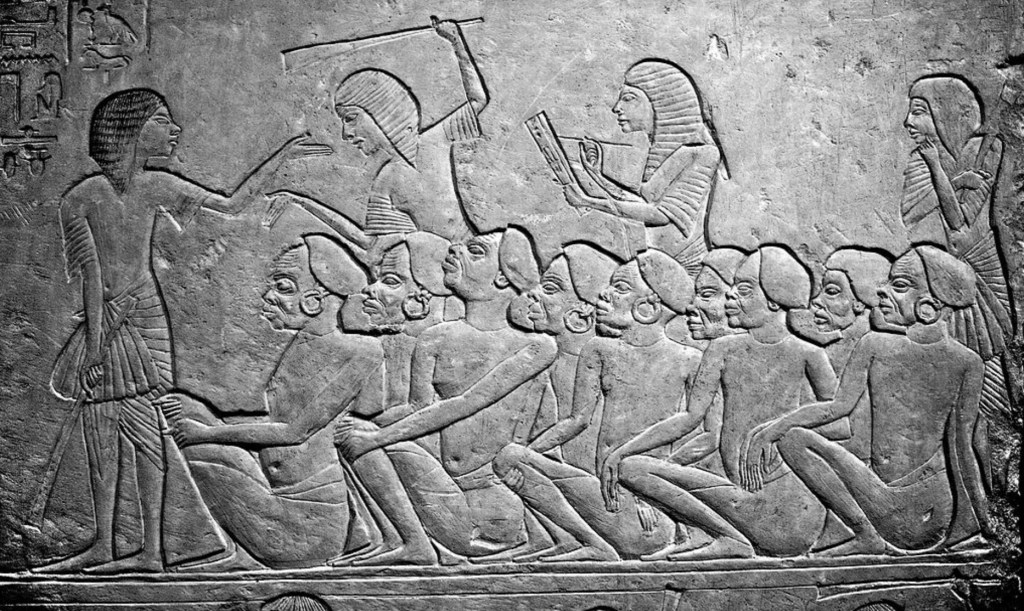

- Ancient Societies and Slaves

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

Origins of African Slave Trade Routes

Africa had been recognised as a source of slaves from at least the time that Caligula was Emperor of Rome between 37 to 41 AD.

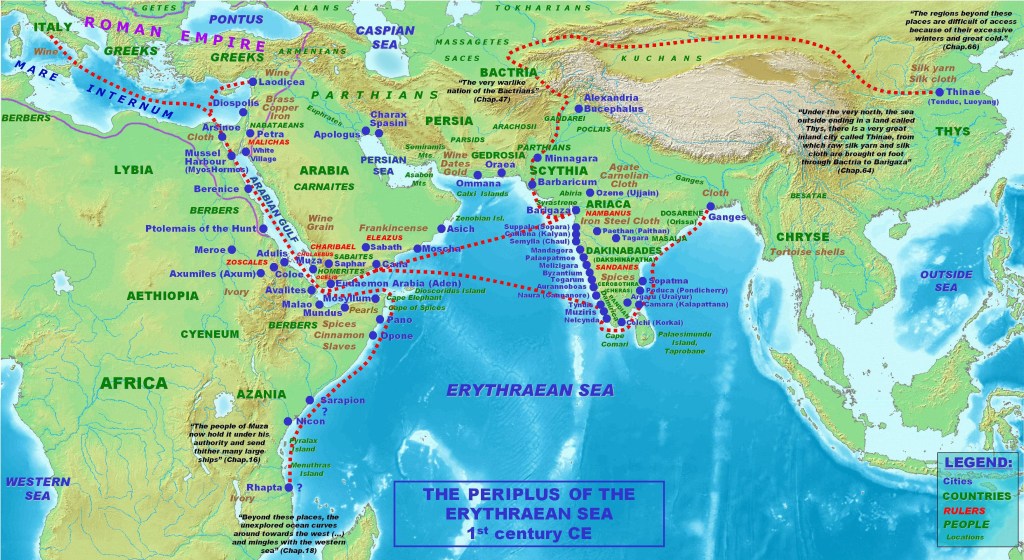

African slaves are mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a sailing guide for the merchants of the Roman Empire describing ports and trading opportunities through the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Indian sub-continent and as far east as modern day Bangladesh and Myanmar and, in the other direction, round the Horn of Africa and south along the east coast of Africa to Rhapta, a lost trading centre that was probably in the Rufiji delta in modern day Tanzania.

For each port along the vast coastline covered by the Periplus the merchants are given notes on navigation, a brief political overview and a list of commodities that can be traded.

The Periplus shows that a merchant sailing from the Red Seas and then round the horn of Africa could “buy and sell” 3 slaves along the route. At Malaô he could obtain slaves “on rare occasions”, or find “better-quality slaves” at Opônê but he is warned they are mostly sent to Egypt. If he has been successful in obtaining slaves he could sail to the island of Dioscuridês where there was a demand for female slaves from the Greek, Arab and Indian merchants who were based there. Today this route would take him from Berbera to Xaafuun in Somalia and then to the Island of Socotra which lies about 230 kilometres to the east-northeast of the Horn of Africa.

However, there is no mention of trading slaves further south down, what would become, the Swahili Coast of Kenya and Tanzania. However it does reveal that Arab merchants had already settled and married local women at Rhapta the most southerly port in the sailing guide. Perhaps the seeds of the east African slave trade had already been sown 500 years before the Portuguese initiated the Atlantic trade.

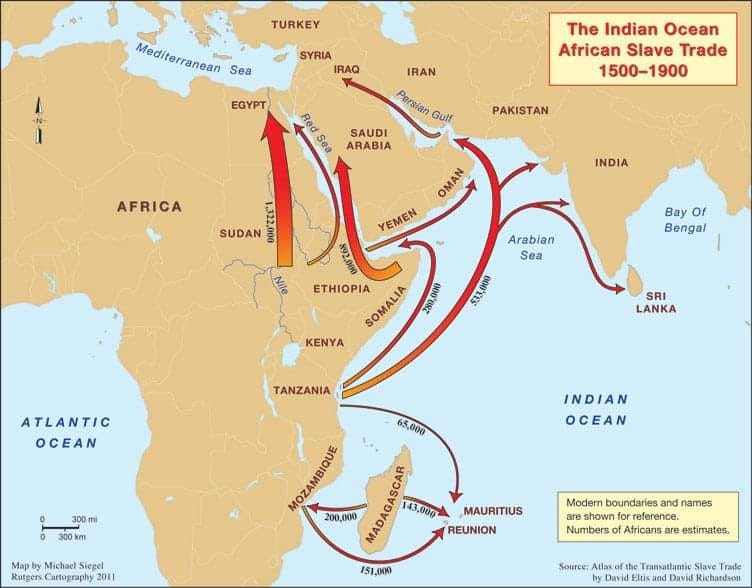

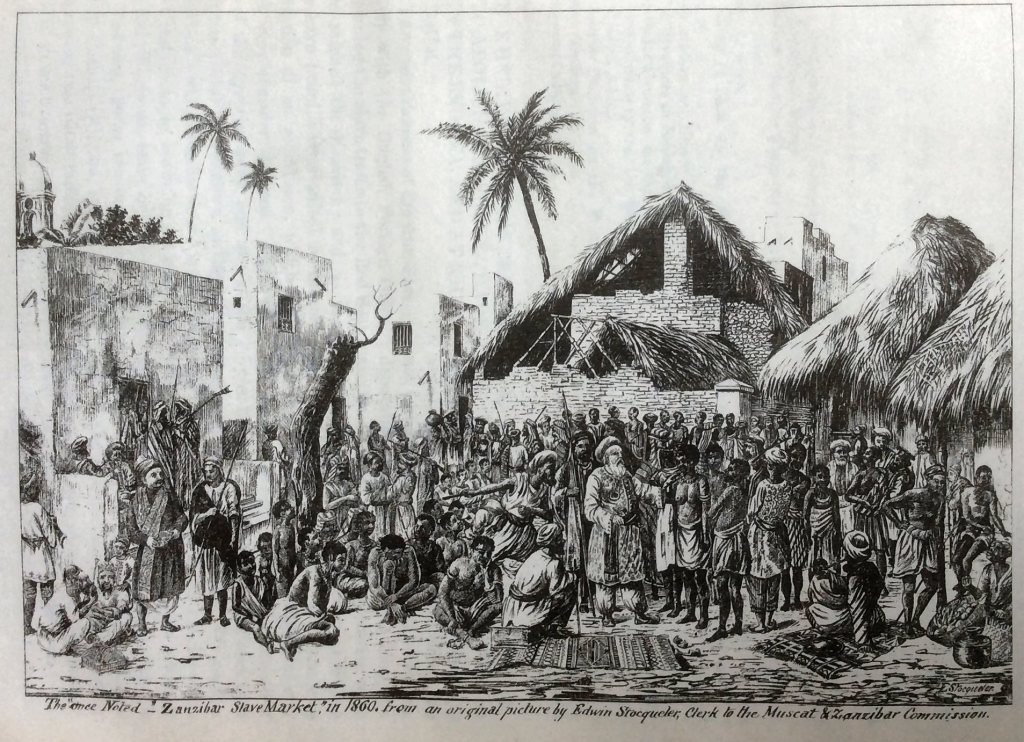

The east African maritime and Horn of Africa slave trade routes carried around nine million Africans to Arabia, Egypt, Persia, Brazil, Reunion, Mauritius, Madagascar, India and Sri Lanka. 4 It is unclear when the northern legs of this trade began but there were African slaves serving in Arabian armies and employed as agricultural workers as early as the ninth century AD 5 and slaves in the Sultanate of Kilwa by 1331 6

From BMC Ecology and Evolution 7

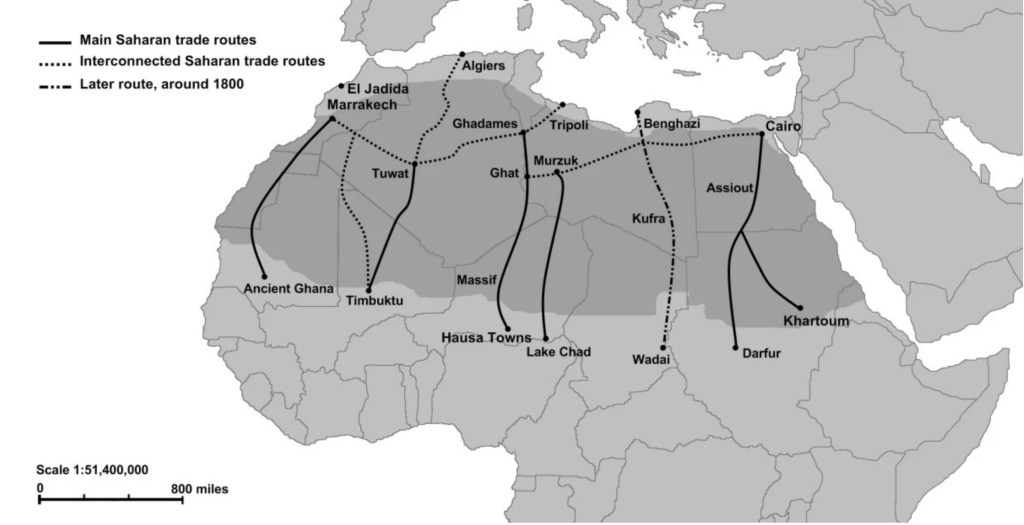

The other, often forgotten, routes crossed the inhospitable Sahara Desert; collectively known as the trans-Saharan route they thrived for seventeen centuries, transporting as many as ten million people from sub-Saharan Africa to Egypt, Persia, Arabia and around the Mediterranean. This trade was so significant that 1/4 to 1/2 of all the North African female gene pool is of sub-Saharan lineages. 8

The estimate that thirty million African people were captured and forced into slavery before 1900 can easily be disputed and argued up or down because the east African and trans-Saharan trades are very poorly documented. It is concerning that apologist historians have muddied the water by promoting the idea that slaves taken to Arabia were somehow well treated and writing that, anyway, the numbers concerned are vastly over estimated. 9

Whether we accept thirty million stolen and displaced Africans or some lesser number it remains a dark episode in human history; so awful that it eventually led to most western countries declaring slavery illegal and withdrawing from both the trade and slave ownership. Subsequently some of those countries dedicated significant resources to the suppression of the trade and it remains high on the agenda of many organisations today.

However, the conversations even more frequently ignore the fact that slavery did not start with these African trade routes and certainly not with the Atlantic slave trade. It existed, at one time or another, in one form or another, in many, perhaps most, of the societies that have waxed and waned across the last five or six thousand years. In practice it is hard to find a modern society that does not have slave ownership somewhere in its history.

Simon Webb, the author of The Forgotten Slave Trade 10, argues that slavery:

“…was a feature of almost all ancient civilisations and it was regarded as being more or less the natural state of affairs in hierarchical societies.”

If slavery was indeed the “natural state of affairs” in ancient societies it appears to have continued to be so through the medieval period and into the early modern and modern eras.

What is Slavery?

Lenski and Cameron11 define slavery as:

“…. the enduring, violent domination of natally alienated 12 and inherently dishonoured individuals (slaves) that are controlled by owners (masters) who are permitted in their social context to use and enjoy, sell and exchange, and abuse and destroy them as property.”

A comparatively tight definition that incorporates the ideas that:

- Slavery is an institution that endures over multiple generations of slaves:

- The slave is dishonoured, i.e. has any social standing denied to them;

- The master is the absolute owner of the slave as property and the sole beneficiary of the slave’s labour.;

- And, it also alludes, by mentioning natal alienation that, across history, the slave is typically “other”, a person taken from elsewhere, or bred from people taken from elsewhere.

The challenge when considering slavery across multiple societies and over long periods of time is that there has been a trend in recent years to broaden the definition of slavery to encompass multiple forms of unfreedom. Damien Pargas13 argues that:

“As scholarship moves to global views of slavery as a human condition, the danger arises that academic understandings of slavery will ultimately encompass virtually all forms of oppression and thereby seem so nebulous as to become meaningless.”

Pargas goes on to explain that slavery should be positioned at the most extreme end of a broad spectrum of “unfree or dependant conditions” and that we need:

“… further clarification of what distinguishes slavery around the world from serfdom, debt bondage, various forms of indentured servitude, imprisonment, peonage, forced labor, and related asymmetrical dependencies.”

This argument develops a new definition or clarification of earlier definitions of slavery:

…. the condition of slavery, in virtually every world society in which slavery existed, transferred to the slaveholder unlimited and potentially permanent power over the enslaved person, including powers related to life, reproductive capabilities, entitlements, and all other attributes. This differed from all other dependent conditions.

There is an argument put forward by some historians that the east African and trans-Saharan slave trade were somehow less awful than the Atlantic trade because some Arab slave markets were carefully regulated, household slaves could be humanly treated, female slaves were often highly valued and the children born as a result of master and concubine sexual relations were born free.

Each of these arguments can be analysed and refuted but it is perhaps more enlightening to look at the judgement passed down by Judge Robert M. Toms at the trial of Oswald Pohl and seventeen other officials of the Nazi SS WVHA 14 who, in 1947, “were charged with conspiracy to commit war crimes and crimes against humanity, and membership in a criminal organisation.” 15 and who were tried at the Nuremberg war crime trials.

The defence had argued that, in many cases, the inmates of concentration camps who had been used as slave labour within the Nazi German war machine had been fed and clothed in the same way as their guards. In dismissing this argument Judge Robert M. Toms, prior to sentencing the accused to be hanged said:

“Slavery may exist even without torture. Slaves may be well fed and well clothed and comfortably housed, but they are still slaves if without lawful process they are deprived of their freedom by forceful restraint.

We might eliminate all proof of ill treatment, overlook the starvation and beatings and other barbarous acts, but the admitted fact of slavery – compulsory uncompensated labour – would still remain.

There is no such thing as benevolent slavery. Involuntary servitude, even if tempered by humane treatment, is still slavery.16

There is no such thing as benevolent slavery.

Do only Slave Societies Count?

Historians have differentiated between “slave societies” and “slave owning societies” based on an idea proposed by Moses Finlay the 1960’s.

Finlay (see right), a brilliant historian with Marxist leanings, argued that a slave society was one in which:

“Slaves must constitute a significant percentage of the population (say, 20 percent or more); must play a significant role in surplus production and must be important enough to exercise a pervasive cultural influence.” 17

Using his own definition Finlay said that, across all human history, there were only five “genuine” slave-societies.

- Classical Greece (excluding Sparta)

- Classical Rome

- Colonial Brazil

- The colonial Caribbean Islands

- The Southern US States before the Civil War

There are two problems with this approach. Firstly it, intentionally or unintentionally, focuses the conversation on just two ancient civilisations and the Atlantic slave trade. This suggests that after the Roman Empire collapsed in Western Europe we enjoyed a world free of slavery, or at least of slave-societies, until the Atlantic Slave Trade started in the 1540s.

Secondly it projects slavery as a “Western” problem by excluding any Middle-Eastern, Asian, African or pre-Columbian American societies. There are strong arguments that he could have included other societies without compromising his own definition.

Lenski and Cameron suggest the inclusion of Chosŏn Korea 1392 to 1910, Ancient Carthage between 400 and 200 BC, the Sarmatians from 200 to 400 AD, the natives of the Pacific Northwest of America in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the Kingdom of Dahomey in the 19th century. 19

Thinking in such formulaic terms is a potential distraction if we are trying to understand the prevalence of slavery globally and across time. It introduces two leagues of societies that accepted and benefited from slavery and by doing this narrows our viewpoint and potentially results in ignoring cultures, that would not be deemed slave-societies, where slavery was still fundamental to the working of that society.

Modern Societies Dependent on Slaves

Below are four examples of modern states who became dependant on slave labour yet fail to meet Finlay’s criteria of a slave society. Non of the four purchased slaves from internal or external markets although one used prisoners of war as slaves and imported and enslaved civilians from occupied territories.

In each case there are strong arguments that the state could not have functioned without their slaves.

Nazi Germany

Holocaust Encyclopaedia20

Nazi Germany does not meet Finlay’s criteria; yet ten million people were sent to concentration camps and many were used, and very often died, as slave labourers in the German industries that were vital to the war effort.

According to the Nazi’s own records, there were over 7.5 million foreign workers in the Reich in August 1944, the overwhelming majority being forced labourers including millions of Soviet prisoners of war captured as part of operation Barbarossa.

Concentration camps were partly commercial operations hiring out inmates to work as slave labour in local industries and German industry built factories near to the camps to exploit cheap and available labour.

By 1945 a total of 14 million people had been exploited as slave labour in Nazi Germany.

It is arguable that Nazi Germany could not have continued to operate and to wage war without slave labour.

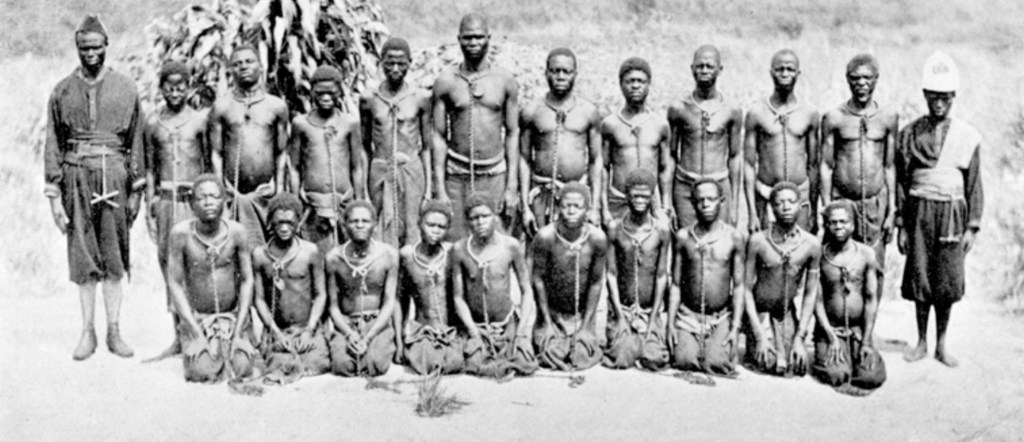

The Belgium Free State

King Leopold II of Belgium took personal control of 2,344,000 km2 of west & central Africa in 1885, an area 76 times as large as his own country, he named it the Belgium Free State. To harvest the valuable rubber latex from the rain forest Leopold mobilised Congolese society to the point where the territory became a vast slave plantation.

Production targets were enforced by a brutal police force who followed Leopold’s orders to punish failure by taking and shooting hostages and hacking off the hands of villagers. Estimates of the death toll vary between 2 and 15 million in less than 20 years.

Leopold’s Belgium Free State was wholly dependent upon slave labour.

Stalin’s Gulags

It was never completed.

The institution of Gulags in the Soviet Union is a more complex example. Between 1934 and 1947 10 million people were sent to “corrective labour colonies”, Gulags, to be “reeducated”.

Before World War II the Gulag system produced a high percentage of the Soviet Union’s valuable metals and timber and during the war was directed to the armament industry. However, Gulag slave labour was very unproductive compared with free employees and was often punitive rather than usefully productive.

Mao Zezong’s Great Leap Forward

A further example of mass slave labour is Mao Zezong’s China where the penal system of “laodong gaizao” sentenced an estimated 50 million people to “reeducation through labour” in 1,000 forced labour camps between the 1950s and the 1980s.

20 million Chinese died as a result. 22 In a country with a population of half a billion people in 1950 it is clear that the labour of 50 million people was not vital to the economy but, like Stalin’s Russia, it was fundamental to keeping a dictator in power.

Ancient Societies and Slaves

None of the above modern examples depended on a trade in slaves or a route by which they were brought to market; only the Nazi’s use of POWs as slave labour fits the historical mould of prisoners of war becoming slaves. The use of concentration camp inmates was transactional in the sense that German industry hired them from the Nazi state but this still a quite different model to the more common forms of commerce in humans that existed from as early as 2,000 BC.

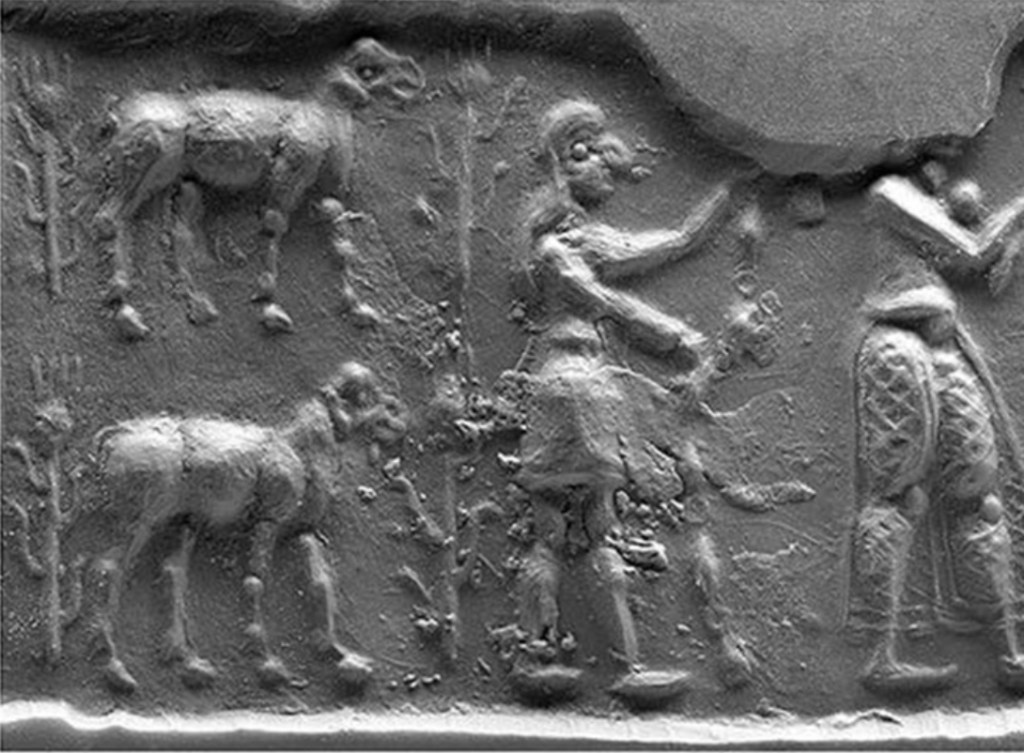

The Old Babylonian Empire

Mesopotamia was the region irrigated by the great Tigris and Euphrates rivers that stretched from close to the Mediterranean in modern-day Syria to Kuwait on the shores of the Persian Gulf incorporating much of Iraq and some of Iran. Within that region and between 2,000 and 1600 BC the “Old” Babylonia empire ruled an area that “corresponds roughly to southern Iraq from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf”. 23

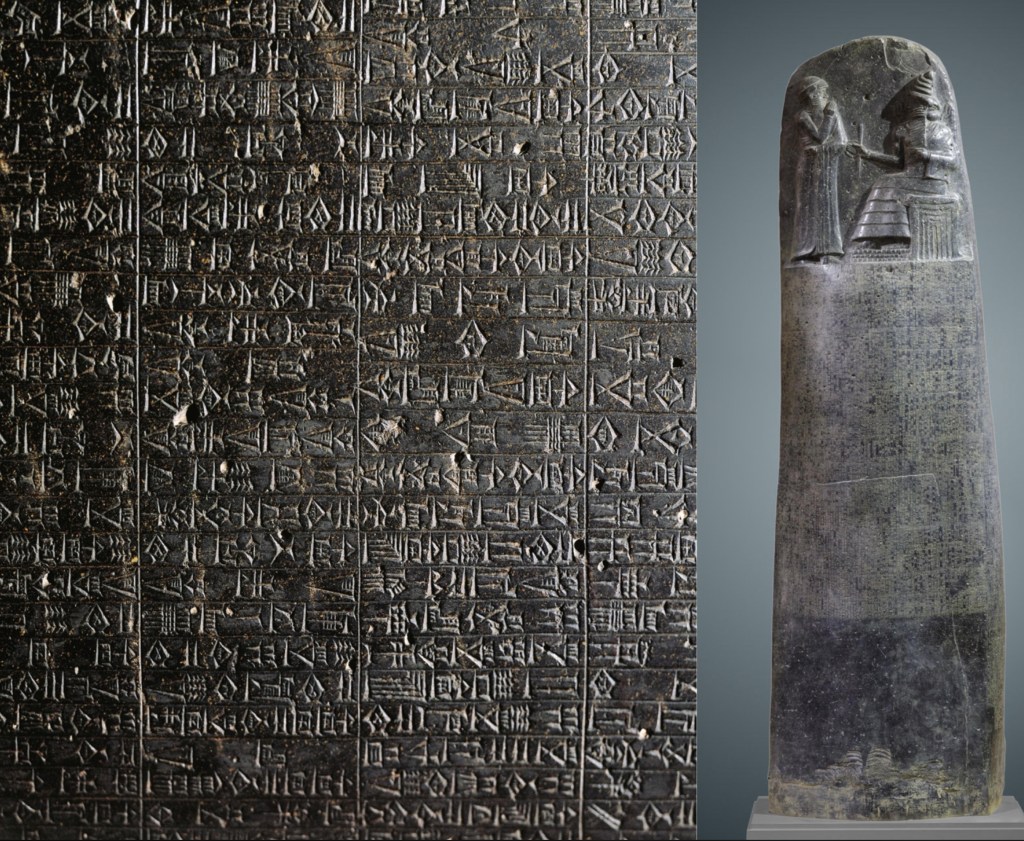

Its most famous king, Hammurabi, who ruled from about 1792 BC to 1750 BC brought most of Mesopotamia under Babylonian rule and issued the Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest known, documented law codes.

This code is one of many sources that historians have used in their endeavours to understand slavery in the Old Babylonian Empire as it mentions “slaves” 24 25 on a number of occasions.

Slaves in the Babylonian Empire performed a wide range of roles including housework, agriculture labour, herding and sometimes provided specialist skills such as weaving. There is evidence pointing to some slaves acting as their master’s agent in business dealings and to female slaves having sexual relations, and children, with their masters.

They were treated both by law and by custom as “others” with a requirement to have specific hairstyles, an “abbuttu-lock”, and possibly special clothing to make them easily identifiable presumably to prevent them passing unnoticed out of a city’s gates, an act that was prohibited by law.

Although some slaves were acquired in far-away non-Babylonian cities there is no indication that there was an active slave market in or near the empire nor any active slave trade routes in the wider region. Prisoners of war were typically ransomed rather than enslaved. This leaves open the question: if the population of the Old Babylonian Empire was around 150,000 to 200,000 people and a bout 5% were slaves, where did between 7,500 and 10,000 slaves at any one time came from?

Based on available texts from the old empire it appears that the majority of people who became slaves did so, perhaps often on a temporary basis, in repayment of family debts. However it is also possible that they were, in effect, used as a financial instrument to purchase a commodity or to borrow money in the same way that a modern company issues a bond to raise capital. A family member would be passed to a seller or lender to use as a slave for a set period of time or until the family redeemed them. In return the family received goods, repaid a debt or a took out a new loan.

Currently at the Louvre

Old Babylonia would fail Finlay’s test through lack of slaves and the output of their labour was trivial so it would have had little effect on the overall economy. However, slaves appear to have acted as an essential financial instrument in an age when few existed and therefore were important to the way the society operated.

Richardson argues that, even though there was only a small number of slaves in Old Babylonian society, around 5% of the population, and despite the unanswered questions surrounding the status of slaves within that society the Old Babylonia Empire was:

“…. “foundational” to the globalisation of the institution throughout the pre-modern world – out to other ancient Near Eastern cultures, which adopted many Mesopotamian standards of price, status, sale formulae, and legal practice – hence to Greece, Rome, the rising Islamic world, medieval Europe, and beyond” 26

On that basis it seems to have been the right place to start looking at ancient societies where slaves played an important role.

To be continued …………..

There is a comment box at the bottom of this post after Footnotes and Other Sources. Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Leave a reply to Historical Perspectives on Slavery Part 3 – Travelogues and Other Memories Cancel reply