- Introduction

- Ancient Egypt (2181 to 332BC)

- The Ancient Greek World

- Footnotes

- Appendices

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

Ancient Egypt (2181 to 332BC)

Many of us were taught at school that the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt (2181 to 332BC) used slave labour to build the pyramids and other monumental buildings. Sunday school developed the theme with colourful drawings showing enslaved Israelites building Egyptian cities or drawing huge blocks of stone on sledges with the pyramids in the background.

However, in recent decades archeologists have found that the Great Pyramid complexes of kings Menkaure, Khafre, and probably Khufu were most probably built by free men living in a large settlement at Heit el-Ghurab near the Sphinx and the Pyramids between around 2600 and 2400 BC. Here workers were housed and materials, carried up and down the Nile by boat,were unloaded and stored. Many of these men must have been skilled craftsmen and perhaps moved between different sections of the great construction projects as full-time professionals whilst other workers possibly spent some part of their lives working on royal or religious construction projects as a form of taxation.

The idea that the thousands of workers living at Heit el-Ghurab were not slaves and might have included troops of elite soldiers is partly based on the large deposits of animal bones and evidence of other foods. They were well supplied with sheep, goats, cattle and pigs along with grain produced in the Nile Valley and olive oil imported from the Levant along with Levantine pottery. Olive trees are unlikely to have been common, or even might not of yet existed, in Egypt prior to the Roman period so olive oil was a luxury commodity during the Pyramid Age. It seems highly unlikely that slaves would have been fed so well.

In practice there is virtually no evidence of large-scale slavery in the long history of Egypt from the days of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 to 2160 BC) until the Ptolemaic Period (332 to 30 BC). Similar to the Old Babylonia culture slavery was limited in scale and mostly domestic in nature.

However, in 2477 BC tomb inscriptions show a number of large sea-going vessels returned from an expedition to “The Land of Punt”, the Egyptian name for the area to their southeast along the coast of the Red Sea and to the Indian Ocean on the shores of the Horn of Africa; today this comprises parts of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. Two of these vessels contained 24 people, a mixture of men, women and children with stylised African features guarded by Egyptians. Archeologists believe they are captives being delivered to the pyramid building area at Abusir.

This and other inscriptions show that the Egyptians were capturing people from the lands around them, Nubia, Libya and Punt, in wars and in raids, and whilst it is probable that some worked on monumental construction projects it appears that many were employed as agricultural workers. In addition Nubian and Levantine prisoners of war were conscripted into the Egyptian Army in the era of the Middle Kingdom (2055 to 1773 BC).

Ella Karev explains that understanding slavery in Egypt before the time of Alexander the Great and the start of the Ptolemaic era is difficult because:

“…… there was little clear-cut distinction between slaves and other coerced labourers in Egypt. Seemingly free people could be abducted and coerced into labor by the state and punished if they attempted to flee; conversely, seemingly unfree people who had been sold as property could hold rights we would not expect from slaves such as owning property, testifying in court, and negotiating the terms of their enslavement.” 2

Consequently, and accepting Karev’s assertion that there was little slavery until the Ptolemaic era we will roll forward 2000 years from the old Kingdom and consider how slavery changed once Alexander’s erstwhile general, Ptolemy declared himself king in 305 BC.

However, before we do that, it makes sense to divert to the Greek world because it is their culture of slave ownership that Ptolemy took to Egypt.

The Ancient Greek World

Minoans c. 3000 to c. 1450 BC

The earliest cultures to develop in the region we now know of as Greece developed in the Cyclades and on Crete. We have no idea what these two societies called themselves and we know them as the Cycladic and Minoan cultures.

They both descended from the first Neolithic farmers of western Anatolia and the Aegean and neither spoke a Greek language. 3

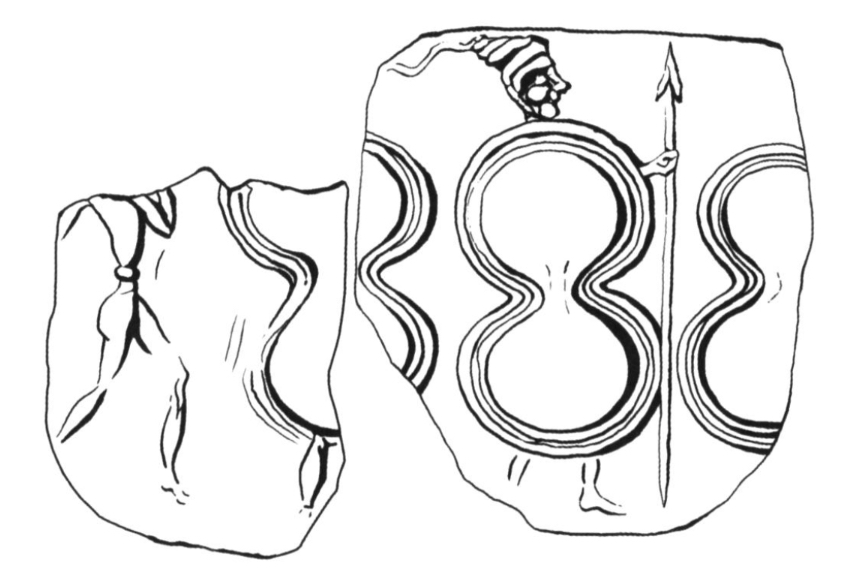

The Cycladic culture produced remarkable statues, some life sized, (see left) as grave goods but left little other evidence that offers an insight to their culture.

By 2000 BC the Minoans dominated the Aegean and were trading far and wide to Egypt, the Levant and Western Asia. They in turn began to fade around 1600 BC at about the time the volcanic island of Thera, modern day Santorini, erupted.

We know there were slaves in the late phases of Minoan society as they are mentioned on tablets found at Knossos. As we saw in the Old Babylonian Empire (here) people could move in and out of slavery through debt and in the ancient world prisoners of war usually became slaves unless they were ransomed. It is thought that both forms of slavery existed in Minoan society and we can reasonably assume that their role was often related to food production although there is some evidence of slaves as metal workers and galley slaves.

For many years the Minoans were presented as a peace loving nation of traders and artisans based on the thin evidence that their frescoes do not depict warfare. However, recent research has shown that it was potentially a much more militaristic society than previously assumed.

The bronze age Minoans were skilled metallurgists and weapon makers reaching a level of “craftsmanship that resulted in some of the most exquisite and effective weapons of the ancient world”. 4 Their weapons included swords which were tapered with reinforced hilts for better grip and balance, daggers, spears and composite bows shooting bronze tipped arrows.

The sophistication of Minoan weapons evidences, not just craftsmanship, but an evolution of design that was probably based on their use in combat over many decades. Finds include swords decorated with ivory, gold or silver, and often with intricate carvings that are unlikely to have been intended for use in combat and were probably crafted for high status individuals as a clear signal of power and authority. There are similarly decorated daggers that were possibly crafted for the ceremonies shown in some of the frescoes found at Knossos.

These frescoes at Knossos are well known and also depict various athletic activities including bull-leaping, boxing and hunting which Barry Molloy says is evidence of military training. 5

Advanced weapons and high status weapons crafted to show that some people are in the upper echelons of a hierarchical society added together with military training suggests the existence of an elite warrior class with high status leaders.

Homer’s epic poem of the Trojan War which took place around 1250 BC after Minoan power had waned and Mycenaean culture dominated the Aegean describes an army with high status, named warrior kings, generals and heroes in command of trained and well armed soldiers. Perhaps this is also how Minoan society had been organised.

There is evidence of a king, wanax, in Knossos and it is thought that he dominated Crete and may have held sway over the numerous Minoan settlements that have been found across the Aegean. Territory on this scale in the bronze age was won and held by whoever could deploy the most powerful military force on land and, in this case, at sea. Warfare meant the capture or execution of defeated soldiers and the civilian population of sacked settlements.

I accept that this is a hypothesis, based, on what appears to be, very limited evidence; however, I believe that Barry Malloy presents compelling arguments that warfare played a part in Minoan society; archeological evidence proves they were well armed with sophisticated weaponry and ancient warfare between city states and emerging empires usually involved the sacking of settlements.

The sacking of settlements in most ancient cultures meant killing the men and enslaving the women and children. I suggest that in the bronze age a dominant, militaristic culture inevitably ended up owning slaves.

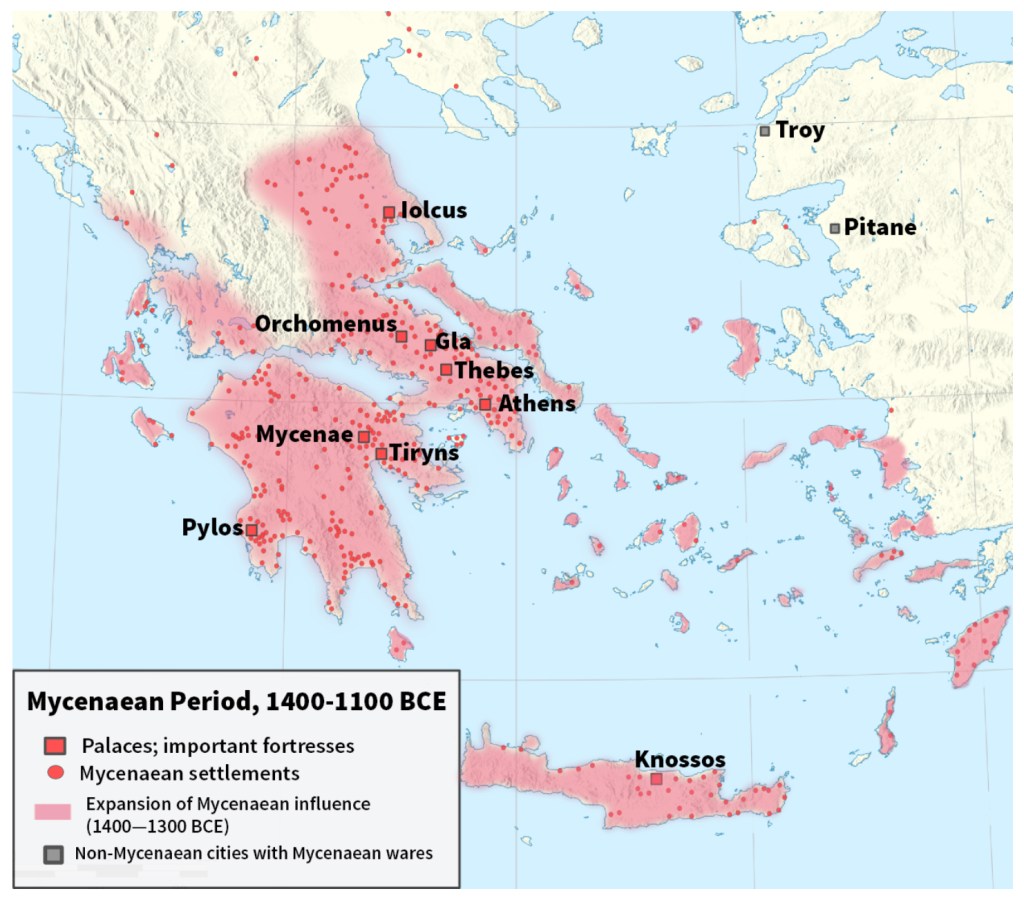

Mycenaeans c. 1700 to c. 1200 BC

The Minoan civilisation began to wane around 1450 BC and what we now know of as Greece and the Aegean came under the influence of the Mycenaeans 8 who are another a society who may never have had a collective name for themselves and more probably people would havre identified themselves with individual settlements.

The Mycenaeans were closely related to the Minoans but their common ancestry of Neolithic Anatolian and Aegean farmers was mixed with DNA from Northern steppe pastoralists. 9 They were living on the Greek mainland at the same time that Minoan culture was developing in Crete and, what might be the oldest, centre at Iklaina was a complex organised society as early as 3400 BC.

From Dr Senta German atSmart History 10

The settlement of Mycenae was a significant centre of power and gave the culture its name but, whilst it may had had some primacy, many other Mycenaean centres developed at the same time including: Pylos, Tiryns and Midea in the Peloponnese; Orchomenos, Thebes and Athens in Central Greece and Ioicos in Thessaly.

In around 1450 BC a number of Minoan settlements on Crete were destroyed and Mycenaean artefacts begin to appear which suggests that Crete came under the political control of the Mycenaeans or were just occupied by Mycenaeans from one or many places on the Greek mainland at this time.

They had been trading with the Minoans for many centuries and their architecture, pottery, art, and religion were all heavily influenced by Minoan culture. It is significant that they also acquired the Minoan’s skills of metal working and Linear B, the Mycenaean form of writing, was derived from Linear A, the still undeciphered Minoan form. 11

Around 1300 BC the fortified palace at Thebes was destroyed and some buildings outside of the citadel at Mycenae razed to the ground. There is evidence of fire and destruction at a number of Mycenaean centres including Mycenae, Tiryns and Pylos around 1200 BC. And, as further evidence of security threats in the region around this time, Mycenae, Tiryns and Athens all strengthened their defences and improved their water supply by building cisterns inside their citadel walls. Linear B tablets at Pylos talk of “the watchers guarding the coast” but we don’t know who they were watching for nor who or what caused the destruction layers that have been excavated.

Between 1250 and 1150 BC the whole Bronze Age world at the eastern end of the Mediterranean dramatically changed. Along with the Mycenaeans, the Hittite Empire, Babylonia, the Levant, the Assyrian Empire and the New Kingdom of Egypt all went into severe decline. There are records of “Sea People” threatening coastal settlements but their very existence and, if they were a significant factor, their origin is open to debate.

Shortly afterwards, in around 1120 BC, Iolkos, the capital of Thessaly, Miletus and Mycenae were all destroyed.

Greece entered a “Dark Age” during which the Mycenaean cities along with their hierarchy and armies largely disappeared as the population declined and retreated from large centres to villages; the skill of writing and many other elements of Minoan and Mycenaean culture was lost. As discussed below Athens survived the destruction and depopulation of the late Bronze Age and was one of the first centres to recover in the early Iron Age.

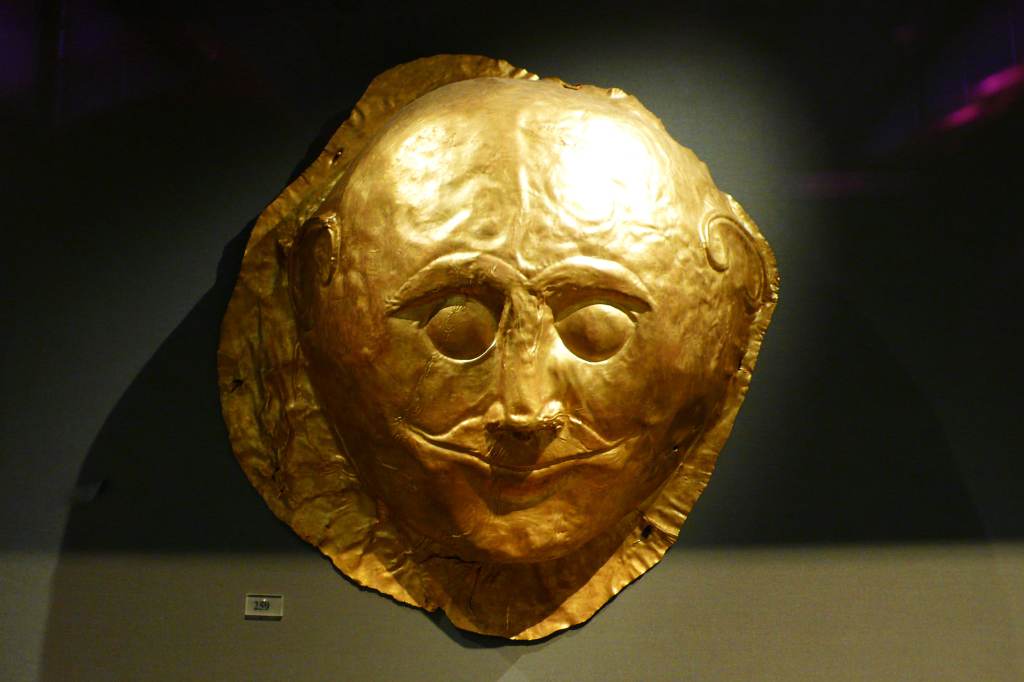

National Archaeological Museum Athens 13

By deciphering the Linear B tablets that record the administrative details of Mycenae it is clear that it was a hierarchical and highly organised society with a king, wa–na–ka, ruling each city, a military leader commanding a elite warrior class, various aristocrats similar to medieval lords and barons, provincial governors, possibly a council of landowners, freemen and, at the very bottom of the social pyramid slaves, male do–e–ro and female do–e–ra. These slaves are sometimes owned by individuals and sometimes by the Mycenaean gods that we know from Homer: Athena, Hera, Hermes, and Zeus. 14

Power was centred around the defended citadels which housed palaces, administrative offices and stores. Politics is much the same in any era so we can guess that the elite classes would have based themselves near the king in these centres perhaps acting like a medieval court. Aristocratic status and power has been associated with land throughout history and it is probable that the elite owned large agricultural estates. From grave goods we see that they possessed great wealth in gold, jewellery and ornate weapons.

To look back beyond the Greek Dark Ages to a time when writing was limited to maintaining administrative records is to view a culture through smoked glass. However, we can make some reasonable assumptions. To give the aristocracy and their warrior elites the time to hunt, keep fit and train and then engage in raids and warfare required, as it did in medieval Europe, an underclass who produced everything.

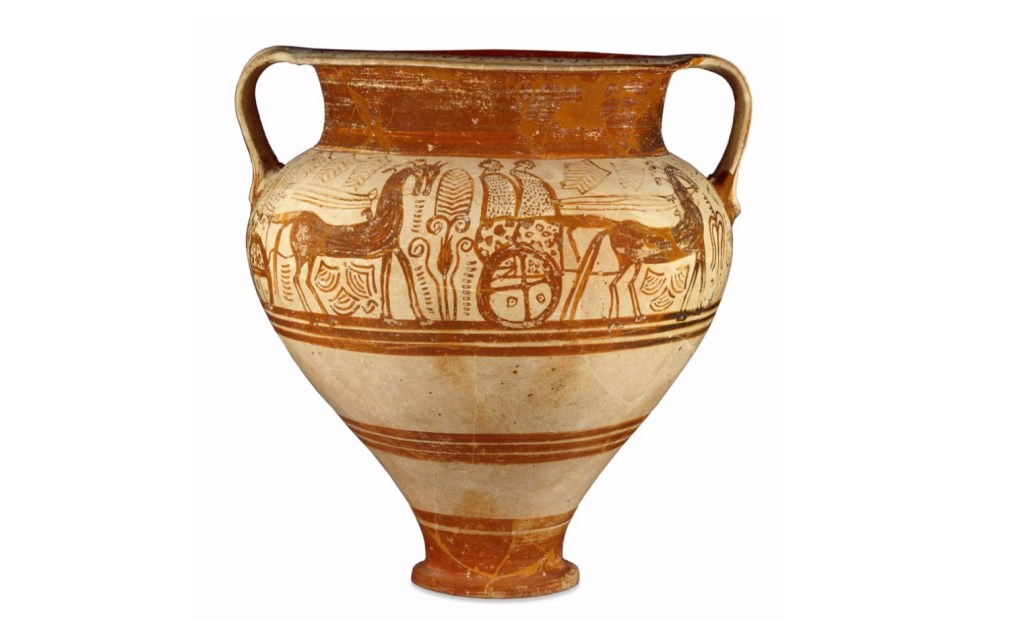

The krater shows Mycenaean warriors marching to war in full armour including helmet, cuirass, greaves, shield, and spear. On the far left, as seen in this detail, a woman waves the soldiers farewell.

Dated to 1200 BC

National Archaeological Museum of Athens 15

In medieval England around half the population were freeholders or serfs working on the land. Whether similar a similar ratio existed in Mycenaean society would depend on a number of factors including whether each centre had a standing army or whether the warrior elite called up small land owning farmers and freemen to serve as soldiers when needed.

However, the scale of the Mycenaean palace complexes, the existence of an aristocracy, an elite warrior class, merchants and sailors and the wealth in grave goods they left behind all suggest that there was a large labour force of:

- agricultural labourers working in the fields and orchards;

- herdsmen caring for herds of cattle, sheep, goats and pigs;

- butchers, bakers and other food processors;

- builders maintaining palace buildings and fortifications;

- shipwrights;

- blacksmiths making and maintaining weapons;

- a wide range of domestic servants;

- soldiers servants including the possibility of shield carriers etc.

British Museum 16

In such a rigid, hierarchical society whether these people on the bottom rungs were chattel slaves, serfs or freemen is a moot point, none of them had much, if any, control over their lives and labour shortages were probably addressed by raiding settlements around the Aegean and Mediterranean.

In Homer’s poems wars and minor raids conclude with defeated men being killed and their wives and daughters being raped and then taken as slaves but it seem likely that the Mycenaeans would also have valued craftsmen. It is likely, for example, that their skill in bronze working was acquired from the Minoans so perhaps many of the specialist trades in the society were carried out by slaves taken as plunder.

Homer’s Poems, History or Myth?

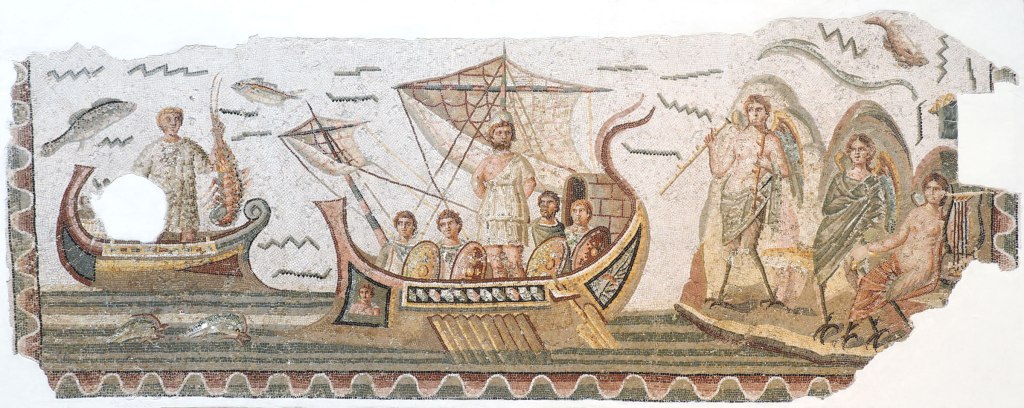

From a Roman mosaic now in the National Brado Museum of Tunis 17

Linguistics and archeology provide a reliable framework for understanding Mycenaean culture and are the only source of real evidence. However, our view of the Greek Bronze Age has been coloured by the poets: Hesiod, who passed down many of the Greek myths that we are still familiar with, and Homer whose two epic poems relate the story of the Trojan War and the return home of one of its heroes, Odysseus, to the island of Ithaca in the Ionian Sea. 18

Homer’s poems are set in the late Bronze Age and it is possible, but far from certain, that one of the destruction layers found at Troy dating between 1700 and 1190 BC is associated with Homer’s Trojan war. However, archaeological evidence is limited to a some sling stones in a destruction layer from 1300 BC that is more likely associated with an earthquake.19

Based on astrological events in the Odyssey some scientists suggest that Odysseus returned home to Ithaca in the spring of 1178 BC. 20 Homer is thought to have lived 500 years later in the 8th century BC so the oral history represented by his poems was already 500 years old in his day and was probably not written down for another 200 years.

Some historian argue that his poems represent the culture of his own times, Archaic Greece, rather than the Mycenaean Bronze Age but others, including linguists, believe that the poems are the product of a long oral tradition and contain an accurate memory of an earlier age. 22

As with many of these discussions, you can see sense in both sides of the argument. In the Odyssey Homer provides a wealth of information about slavery which rings true as fact rather than fiction and in trying to understand the prevalence and nature of slavery in ancient Greece it is not essential to position this information specifically in either the Mycenaean or the Archaic age but to accept that it probably reflects both societies to a greater or lesser degree.

The Odyssey and Slavery in Mycenaean and Archaic Greece

The Odyssey is an epic poem in every regard, it is sweeping narrative of the Odysseus’ return home to Ithaca from the siege of Troy and his journey there through a mythical world of monsters and gods. As much of the story takes us into the palaces and lives of the elite Mycenaeans and into the homes of ordinary people it provides an insight into, what may be, a cocktail of Mycenaean and Archaic Greek culture at the cusp of the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age.

Emily Wilson’s recent translation of the Odyssey is refreshingly contemporary, straight forward in language and tone. 24 Her translation notes that accompany the poem provide an interesting view on how the work has been historically translated and understood. Most relevant to this writer is her explanation that the Homeric Greek word “dmoe” meaning “female house slave” has historically been translated as “maid” or “domestic servant” which infers a free servant and suggest the homes of Mycenaeans had similarities with Victorian British stately homes rather than describing a slave society. She has translated dmoe as slave and guides us to recognise that “house girl” and “house boy” refer to the antebellum American South and are also slaves.

Slaves are mentioned over 200 times in the Odyssey. At times they are an essential part of the narrative and we learn their names and part of their own story. More often, they are mentioned in passing as background detail in the story. A typical example of domestic slavery is when the goddess Athena visit Odysseus’ hall before his return and sits down to talk to his son Telemachus.

“A girl brought washing water in a jug of gold, and poured it on their hands and into a silver bowl, and set a table by them. A deferential slave brought bread and laid a wide array of food, a generous spread. The carver set beside them plates of meat of every kind, and gave them golden cups. The cup boy kept on topping up the wine.

This short passage describes how a high-status stranger is entertained in elite society. She is served by four different people who are nearly certainly all slaves.

Bottom image – Odysseus slaying the suitors of his wife Helen.

From the details of red-figure skyphos from Tarquinii, c. 450 BC in the Staatliche Museum, Berlin 26

Another insight into domestic life is when Odysseus meets the Phaeacians and visits the “lovely” town of Scheria. The king’s daughter, Nausicaa, is central to this part of the story. We first meet her asleep in her room:

“Slaves were sleeping outside her doorway, one on either side; two charming girls with all the Grace’s gifts.”

The slave girls have been selected as companions of a princess for having “all the Grace’s gifts“, the Graces were: Aglaea “Shining“, Euphrosyne “Joy“, and Thalia “Blooming“. The slave as jewellery, a beautiful possession to show the good taste, wealth and status of her owner.

In a dream Athena tells Nausicaa she needs to visit the washing pools to get her laundry done as her “clothes are lying in dirty heaps”. When she awakens she remembers her dream and goes to see her parents, her mother is spinning yarn surrounded by her house girls and her father is on the way to a meeting. He agrees to let her use a mule cart to take her clothes to the river and says:

“Go on! The slaves can fit the wagon with its cargo rack. He called the household slaves, and they obeyed. They made the wagon ready and inspected its wheels, led up the mules, and yoked them to it.”.

Her mother gives her a picnic to take with her and oil to use after she bathes.

“Then Nausicaa took up the whip and reins, and cracked the whip. the mules were on their way, eager to go and rattling the harness, bringing the clothes and the girl and all her slaves.”

by Friedrich the Elder Preller 1864 27

Nausicaa’s slave companions remain unnamed and uncounted throughout the next part of the story where they wash her clothes and play games with Nausicaa. Odysseus is lying exhasusted on the beach and is woken by their voices. He calls to Nausicaa, whilst hiding his nakedness with leaves. She provides him with some of the clothes she was washing and he walks back to town following her cart along with her slaves.

Once inside King Alcinous’ palace we hear of more slaves:

“The King had fifty slave girls in his house; some ground the yellow grain upon the gallstone, others wove cloth and sat there spinning yarn.”

Once Odysseus has introduced himself to the king and queen the house girl is ordered to get food from the store. A slave girl brings him water to wash and a “humble” slave brings bread and meat. Pontonous, our first named slave in Alcinous’ papalce is told to go and mix wine for their guest. There are other mentions of slaves who clear the dishes and when Queen Artete notices the clothes her daughter had given him we are reminded that she “wove them herself, with help from her slave girls.”

By Taco Hajo Jelgersma 1717 – 1795 at The British Museum 28

The story of Odysseus’ visit to Alcinous, Arete and Nausicaa is interspersed with descriptions of the glories of the palace, the bronze covered walls, gold jugs, silver bowls, fine woven cloth, four acres of orchards “luxuriant with fruit”, a fertile vineyard, and a hall with the realm’s lords and ladies eating and drinking on ‘soft embroidered throws” lit by gold stars of boys holding torches.

It is an inventory to describe the great wealth and high status of the king, his family and the kingdom’s elites. We are told they lack for nothing. The slaves are part of that inventory, the story-teller is using them to describe wealth and social standing just as he had used the gold jugs and statues.

Apart from Pontonous, the wine boy, they are nameless and often uncounted; slavery is so normal and banal that slaves appear and disappear throughout the text as literary devices, the extras in a crowd scene, the painted backdrop on a stage.

From a frieze at the temple of Apollo at Bassae 5th centuary BC

There is an even darker side to slavery in the odyssey; early in his voyage home, Odysseus and his crew are blown off course to the town of Ismarus in ancient Thrace, modern day northern Turkey. Odysseus tells the story:

“A blast of wind pushed me off course towards the Cicones in Ismarus. I sacked the town and killed the men. We took their wives and shared their riches equally among us.”

The enslavement and rape of the women of Ismarus is described in four words “We took their wives“; their subsequent fate is not mentioned. They are taken, used and discarded when Odysseus and his crew take flight to escape the Cicones’ counterattack. At the end of this brief story he laments the bad luck Zeus has sent them “Poor us” he says.

Throughout the Iliad and the Odyssey and in Greek art abduction, enslavement and rape is treated as a matter of fact, just normal behaviour; women are the spoils of war. Homer’s brief and superficial description of Odysseus and his crew pillaging Ismarus and raping the women makes complete sense to the 8th Century audience as the, unremarkable, way of war. It requires no explanation or apology, in fact Odysseus is later given the honorific the “sacker of cities”.

The Odyssey introduces us to many other slaves in a narrative that continues to revisit the themes described above. But, there is one more chilling example of how a slave is chattel property, a person as a possession that can be disposed of by its owner and whose very status as a submissive being leads to a tragic end.

After killing the 108 suitors who have haunted his home and consumed his stores whilst courting his wife Penelope Odysseus asks Eurycleia, his old nanny and herself a slave, which of the slave women in the household have dishonoured him. Eurycleia answers:

“In this house we have fifty female slaves whom we have trained to work, to card the wool, and taught to tolerate their life as slaves, Twelve stepped away from honour.”

They call all the slave girls to clear out the corpses of the suitors and clean the hall but once that is done he instructs Telemachus to:

“Take out the (twelve) girls between the courtyard and the rotunda. Hack at them with long swords, eradicate all life from them. “

“They will forget the things the suitors made them do with them in secret, through Aphrodite.”

Telemachus takes the twelve girls to the courtyard as instructed but says:

“I refuse to grant these girls a clean death, since they poured down shame on me and Mother, when they lay beside the suitors.”

So, he hangs them.

….. just so the girls, their heads all in a row, were strung up with the noose around their necks to make their death an agony. They gasped, feet twitching a for while, but not for long

The twelve remain unnamed in life and death; apart from the brutal nature of their murder we are told nothing of them, far less that we are told of Nausicaa’s slaves, the “charming girls with all the Grace’s gifts”. They are a literary device to show how Odysseus and, his son, Telemachus value their honour. An honour that would be tarnished by keeping slaves who had been forced to have sex with the elite men who were partying in their master’s hall.

This casual, offhand attitude, to slavery, rape, and murder persists throughout the Odyssey and the Iliad. The storytellers, poets or wandering bards owed their living to the aristocracy who rewarded them for performing in their halls. As such these stories reflect attitudes of the elite and were probably shared across Minoan, Mycenaean and Archaic Greek culture and, as we will see later, persisted in Classical Greece and beyond to the Romans.

These were societies with a landowning and warrior elite whose peacetime pursuits of training as warriors, hunting, feasting, debating the great issues of the day, listening to music and to the stories told by wandering poets was made possible by a huge underclass of slaves.

As we will see.

To be continued ………..

Please let me know if you have any thoughts on this subject and whether you found this post useful.

Leave a reply to Historical Perspectives on Slavery Part 3 – Travelogues and Other Memories Cancel reply