Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

Pre-Roman Europe

The Egyptians, Persians and Greeks left us varying amounts of information about themselves and each other; initially this is in the form of inscriptions and then later the written word. But, when we start to look at Europe before the Romans started to dominate we have no written words other than from the Greeks and the Romans who at best were outside, looking in or at worse had a political or cultural axe to grind. We are therefore very reliant on archaeology which often sheds light into the dark corners of history.

Germany

In the Lech Valley in Southern Germany archaeo-geneticists led by Alissa Mittnik 1 have gathered and compared DNA from 104 individuals buried between 2500 and 1700 BC. This was a period when Anatolian Neolithic farmers were slowly becoming the dominant society but were still living alongside hunter-gatherers and steppe pastoralists.

The DNA results show the farmers to be a hierarchical society with people living in close proximity in extended family groups. High status men inherited their social standing and stayed in the valley but their female partners came, as adolescents from other, and quite often distant, communities. The high status men and women were buried with extensive grave goods.

The results also show that there were locally born, low status people, living with, but unrelated to either the high status men or women and, when buried, had few if any grave goods. The archaeologists concluded that the low status individuals were probably slaves.

Tactitus, the Roman historian, describes slavery in pre-Roman Germany as agricultural in nature and similar to a tenant farmer; the slave working an allotted piece of land and paying his master in cattle, grain or cloth. The slave was owned by the landowner and was passed in inheritance along with the other property on the farm.

Julius Caesar wrote that the Suebians, who lived in the Elbe River area, were the most warlike of the German tribes. He also said that they allowed foreign traders into their lands to purchase the spoils of war that they had plundered from other tribes. It has been argued that as men’s jewellery would have been kept by the victorious warriors and cattle would have been far too valuable to to trade away the booty available for sale was most probably enslaved prisoners of war. 4

Scandinavia

Martin Mikkelsen 5 is another archaeologist who has challenged the conventional view that slavery is invisible to archaeology. He has reviewed the archaeological evidence from a large number of bronze age houses that occupied an area of modern day Denmark for at least 1,000 years up to 450 or 400 BC.

Mikkelsen 7 argues that farms with a single longhouse and owned by high status individuals, as shown by bronze sword ownership, were internally organised to accommodate the family in the western end and slaves in the eastern end of the building. On farms with two longhouses the smaller house was for slaves. Slaves were probably being used as farm labourers, barrow diggers, and herders or to undertake low skilled tasks such as working the bellows in a bronze caster’s house, grinding cereals or as flint knappers.

Other factors suggest that high status Bronze Age Danes were trading slaves for tin and copper to make bronze. This is partly suggested on the basis that there was a demand for miners and other labourers in metal mining and production areas and high status people with no local access to bronze weapons, jewellery or ornaments only had common agricultural; products to trade other than slaves.

Gaul & The Celts

The Celts were the first organised and sophisticated society that we know of north of the Alps. A group of related tribes sharing a common language and culture who first appeared in history in the 8th century BC and eventually colonised Europe from the Iberian peninsular to the borders of the ancient Greek world and north to Belgium and the British Isles.

As early as 600 BC the Greeks founded Marsalis, modern day Marseille, as a trading entrepôt on the fringe of Celtic Gaul and began trading with the Celts whom they called the “Caltha” or “Gelatins”. A hundred years later the Etruscans had expanded to northern Italy and were also trading with Celtic tribes across the Alps.

The Greeks and Etruscans offered wine, pottery vessels, fine bronze weapons, ivory, coral and coloured glass and, in exchange the Celts had an abundant supply of salt from the mines near Hallstatt in Austria, tin from Britain and Brittany, as well as iron, gold and furs.

However, events in Archaic Athens were to make another commodity especially valuable. In around 600 BC, Solon, an Athenian aristocrat reformed the Athenian political and legal systems. Amongst many significant changes he made the enslavement of citizens illegal and abolished the practice of debt slavery where poor farmers had been forced to secure loans from the ruling aristocracy by effectively, mortgaging their own body. Under this system significant numbers of farmers had failed to repay loans and as a consequence not only forfeited ownership of their land but had become, at best, serfs and often slaves working on their lender’s land.

Solon returned all forfeited land to its original owners and freed enslaved citizens. As a renowned poet he wrote of this achievement:

“These things the black earth…could best witness for the judgment of posterity; from whose surface I plucked up the marking-stones10 planted all about, so that she who was enslaved is now free.

And I brought back to Athens… many who had been sold, justly or unjustly, or who had fled under the constraint of debt, wandering far afield and no longer speaking the Attic tongue; and I freed those who suffered shameful slavery here and trembled at their masters’ whims.“

The consequence of these reforms was to create a labour shortage that, in turn, stimulated rapid growth in the, already well-established, slave trade. Athens imported slaves from all around the Eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, the Levant, Macedonia and the Balkans and from around 600 BC the Celts in contact with the greek merchants in Marsalis would have quickly learnt that slaves were in high demand.

As a commodity slaves had the disadvantage of needing feeding and controlling en route but their overwhelming advantage was they could not only walk to market under their own power carrying the food they needed to survive but they could carry all the other commodities the Celts had to exchange. As discussed elsewhere (here) this ability to act as a porter was so fundamental to the ivory trade in 18th and 19th century east Africa that the ivory and slave trade became entwined into a single business.

Based on a wreck found in 2018 in the Black Sea.11

Once acquired by a Greek trader in Marsalis the slaves would have been transported by sea as part of a mixed cargo to various Greek city states for sale. David Lewis 12 describes one such voyage that took place in the late 4th century BC from Bosporos, in eastern Crimea, to Athens. A ship’s master called Lampis, himself a slave or a former slave, appears to have left Bosporos overloaded with a remarkable 300 slaves as well as cargo of 1,000 hides; the ship sank not far from its point of departure.

In the centuries leading up to the Second Punic War (218 – 201 BC), after which Rome is on the path to dominance, the Greek and Etruscan traders drew the Gauls into the Mediterranean world by satisfying the Celtic elite’s every growing appetite for wine and luxury goods and in return shipping tens of thousands 13 of slaves to Greece and Italy. This trade seamlessly continued into the Roman era.

Britain

Copper from the Great Orme mine in North Wales, which operated from around 1850 to 1400 BC, has been found in bronze artefacts from Brittany to the Baltic and as far south as the modern day borders of Germany and Switzerland 15 and copper axe heads from Great Orme have been found in France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Denmark and Sweden so it is clear that North Wales, and by inference Britain as a whole, was connected to a widespread trade network. 16

Copper had been mined in Britain since at least 2000 BC but it was a relatively abundant mineral in Bronze Age Europe with extensive mines in the Balkans, the North Tyrol in Austria and Southern Germany. In contrast, tin, the other element needed to make bronze, was far less common. In the Southwest of Britain in modern day Cornwall and Devon there were accessible and easily worked deposits of tin with a high level of purity.

Around 325 BC the Massalian Greek geographer, navigator and mariner, Pytheas, visited the tin mines at Belerion , modern day Cornwall. Unfortunately his account the, Peri tou Okeanou (On the Ocean), is lost but referred to by later geographers and historians who presumably had seen copies. 18

Pytheas wrote that the Britons were trading their tin from an island that was only accessible at low tide which some historians believe is a description of St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall. Others believe it describes Hengistbury Head in Dorset. Whichever the case the tin was shipped to Gaul before being taken to the Mediterranean via the Gironde-Rhone or Loire-Rhone trading routes.

Strabo a Greek historian and geographer lived from 64 BC to sometime after 21 AD.

Between about AD 7 and AD 18 He wrote a Geography in which he described the people and countries known to the Roman-Greco world at that time.

Strabo died twenty-two years before the Roman Invasion of Britain that led to nearly 400 years of occupation. He, had read Pytheas’ account which in part he professed to disbelieve and would probably have heard stories of Britain from traders, as well as having read Caesar’s account of his failed expeditions in 55 and 54 BC.

He had also seen enslaved Britons in Rome:

“The men of Britain are taller than the Celti, and not so yellow-haired, although their bodies are of looser build. The following is an indication of their size: I myself, in Rome, saw mere lads towering as much as half a foot above the tallest people in the city, although they were bandy-legged and presented no fair lines anywhere else in their figure.” 19

In Strabo’s day tribal leaders in Southern Britain were trading with Rome, with plenty of archaeological evidence that wine and other luxury goods was being imported but more interesting is Strabo’s description of what the Britons were exporting:

“It (Britain) bears grain, cattle, gold, silver, and iron. These things, accordingly, are exported from the island, as also hides, and slaves, and dogs that are by nature suited to the purposes of the chase.” 20

The imported mediterranean goods in Bronze and Iron Age Britain leave traces in the archaeological record but there is no direct evidence of slaves being traded in return. Of course, in practice, it would take slave chains to be found in a wreck of a Greek or Roman trading vessel off the coast of Southern England to provide definitive proof. However, a lake on the island of Anglesey in Wales offers evidence that slaves were being moved from place to place in Iron Age Britain.

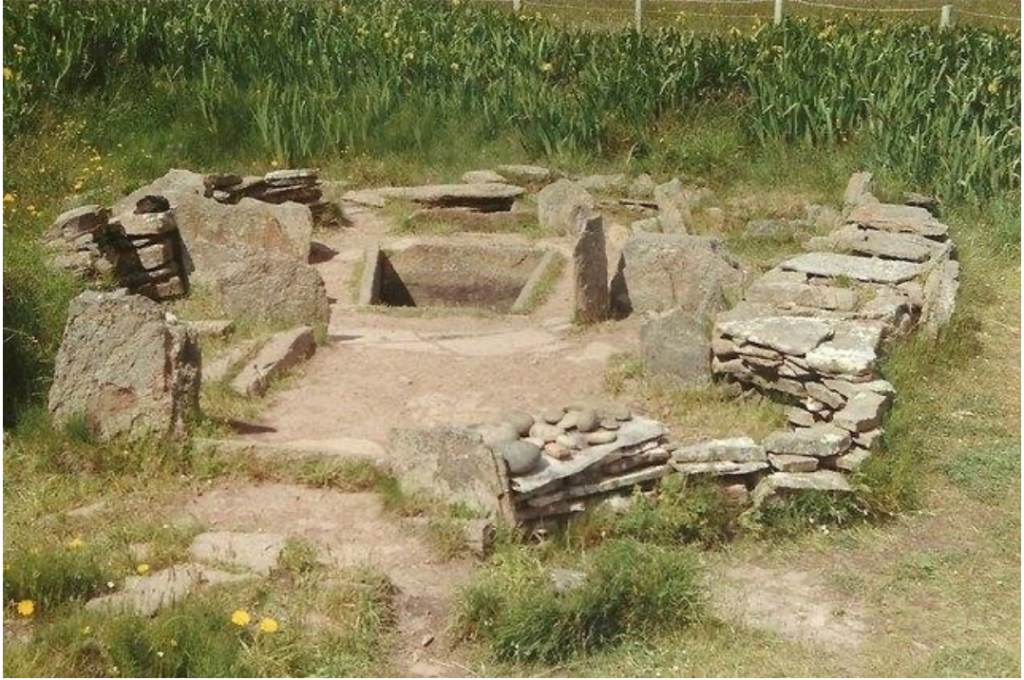

In October 1942, at the height of the War in the Atlantic, RAF Rhosneigr, a WWII airfield was being extended. The construction work turned up a well made, 3 metre long, iron chain that over time led to further searches and excavations that, in turn, led to the discovery of 150 items that form, what is known as, the Llyn Cerrig Bach hoard.

It is now understood that the site was a lake or bog where votive offerings were being made for 500 years from the 4th century BC until the 1st century AD. The deposit includes parts of a war chariot, bridle bits, swords, daggers, parts of a shield or shields, blacksmithing tools, sickles, iron ingots, pieces of cauldrons and decorative bronze items. The metal artefacts are pre-dated by the bones of oxen, horses, sheep and goats.

In the Bronze and Iron Age people deposited items, often newly made but broken, into particular places in lakes, rivers and bogs. They are thought to have been offerings to gods or the ancestors and the act of breaking, an otherwise, functional weapon or craftsman’s tool and depositing it in water might have symbolised moving that object from the land of the living to the land of the ancestors. 22

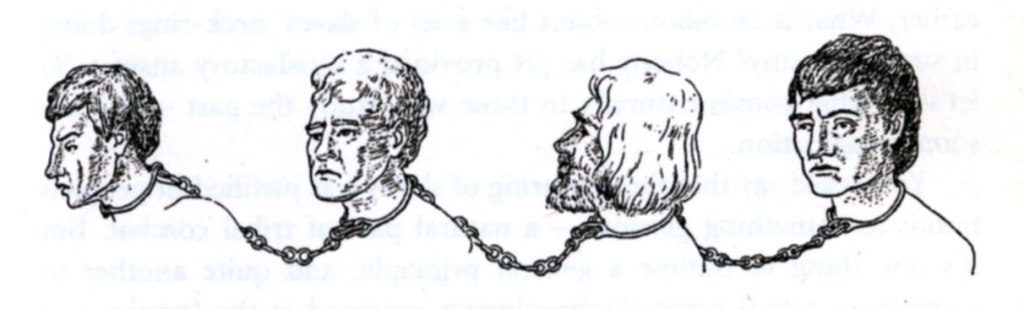

But, let us return to the chain or chains as two have been found. They were made with great skill and craftsmanship and deposited in the lake around 100 BC. One chain has four and the other five neck rings separated by about 1/2 a metre of heavy chain. Their purpose was to shackle slaves and are designed to allow individuals to be added or removed from the group.

We cannot know how and why the two slave chains were deposited in the lake and whether the slaves they once restrained were sacrificed or freed or whether like the blacksmiths tongs they were just someone’s, a slavers’ tools of his trade. They certainly tell us that slaves in pre-Roman Britain were being moved and that slavery or slave trading was common enough to invest in well made and therefore expensive items.

These chains are not unique. Shackles have been found at Bigbury Camp near Canterbury in Kent. They are lighter and less well made as the Llyn Cerrig Bach chains but the design is similar. It appears likely that people were being regularly enslaved and moved in chain gangs to Roman traders in the south.

How Exchanging Wine for Slaves Expands an Empire

Diodorus Siculus, (Diodorus of Sicily) a Greek historian writing in the 1st century BC talks about the Gauls:

“The Gauls are exceedingly addicted to the use of wine and fill themselves with the wine which is brought into their country by merchants, drinking it unmixed, and since they partake of this drink without moderation by reason of their craving for it, when they are drunken they fall into a stupor or a state of madness.

Consequently many of the Italian traders, induced by the love of money which characterises them, believe that the love of wine of these Gauls is their own godsend. For these transport the wine on the navigable rivers by means of boats and through the level plain on wagons, and receive for it an incredible price; for in exchange for a jar of wine they receive a slave, getting a servant in return for the drink.”

The Celts were expert beer and mead brewers with drinking and feasting playing a fundamental role in their culture; it was an important social activity and a confirmation of tribal hierarchies bringing the tribal leaders, who provided the food and drink, and members of the tribe together.

Generosity was considered an important virtue and visitors could expect to be welcomed and entertained with feasts before any business was discussed and feasting would also have been of great importance in forming alliances between tribal leaders.

All these social, business or political events involved the consumption of large quantities of alcohol; both Plato and Diodorus Siculus accused the Celts of drunkenness.

Diodorus suggested that the rate of exchange was one amphora of wine to one slave but Barry Cunliffe 27 believes that it was more complex than this. Cunliffe argues that the Celts were a gift-giving culture that the Greek, Etruscan and Roman traders manipulated once they realised that giving a Celtic chieftain an amphora of wine as a gift meant they would be given a slave in return. The slave once taken back to Rome, for example, was worth 6 or 7 amphora of wine.

The fact that the Celts were a gift-giving culture probably determined how wine was onwardly distributed. There was an established practice of gifts flowing downwards from tribal leaders and tribute in the form of raw materials or finished goods flowing upwards. Before there was significant contact with the Mediterranean world tribal leaders had limited access to appropriate, prestigious gift items but taking delivery of an amphora of wine that could be divided into smaller containers as gifts would result in an increased upward flow of the most valuable raw materials, namely slaves.

Around 15,000 Gaulish slaves a year were needed by the markets in Rome and in exchange the tribal leaders on the borders between the Mediterranean and Celtic worlds acquired luxury goods and wine, lots of wine. Over time these chieftains became increasingly Romanised in their tastes and habits, often building Roman style houses with heated dining rooms where Italian wines could be drunk in elegant and fashionable surroundings. They became the interface between the Roman traders and tribes in the interior but rather than dealing directly with those tribes they dealt with entrepreneurial, and highly mobile, middle-men.

Karim Mata, in his interesting study of slaving in Northwest Europe, points to unusually grave-goods-rich burials in, what are otherwise, farming areas. These “sumptuous burials” contain horse and horse-drawn vehicle equipment suggesting in Mata’s view that they could be interpreted:

“not as the final resting place of sedentary rulers of local farming communities who maintained limited long-distance connections, but instead of members of mobile groups that combined pastoralism and horsemanship with specialist craftsmanship and trading………… it is highly likely that these itinerant groups regularly entered Northwest Europe in pursuit of a distinct resource, namely human captives.” 30

These travelling traders were possibly visiting tribal leaders offering, wine, a desirable product that would bring great prestige to the chieftain at his next feast in a world where prestige cemented tribal bonds and strengthened the hierarchy.

The tribal leaders became highly motivated to acquire the slaves they needed to trade for wine and the only way they can this is by raiding other communities. Thus creating a slave raiding, slave cropping and slave trading economy which destabilises Gaul and later Britain. Roman writers describe the regions beyond Romes borders as being in turmoil; Celt fighting Celt in endless tribal conflicts, they tend not to mention the cause.

The archaeological record shows that western Europe in the late Iron Age was a period of increased instability with a significant increase in hill fort construction, often in remote areas. Mata believes that this surge in the building of defensive structures was the creation of tribal refuges as a direct result of increased slave raiding across the region. 31

It is clear that over a long period of time the wine for slaves trade destabilised and weakened whole regions and eventually, the Roman legions march in, often by invitation from the elite border Chieftains whose wealth has created more enemies than they have the strength to resist.

Of course, the Romans were not invading as a police force to bring peace to the region; they wanted direct access and control over the raw materials that kept Rome working – grain, metals and slaves.

Conclussion

Quite clearly this is not a comprehensive survey but it does show two distinct types of slavery in pre-Roman Europe. In Bronze Age southern Germany and Denmark farm houses appear to have been designed to accommodate an elite family and their slaves.

Whilst in Bronze and Iron Age Gaul and Britain slaves are being sold in large numbers to Greek, Etruscan and then Roman traders causing instability and eventually leading to Roman occupation.

There was an insatiable demand for slaves from Greco-Roman world over a very extended period of time, hundreds of years. A demand that remained at high levels with sophisticated and efficient trading systems and well established lines of supply. The Mediterranean world was a vortex into which slaves from any society that could be labelled “other” were remorselessly drawn for hundreds of years.

Leave a reply to stevemiddlehurst Cancel reply