- Introduction

- The Scramble for Africa

- The Myth of the Empty Land, res nullius

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Appendix A – The Ports and Trading Centres of the Periplus

- Appendix B – Europeans, Great Zimbabwe and the Myth of the Queen of Sheba

- Other Sources and Additional Reading

Introduction

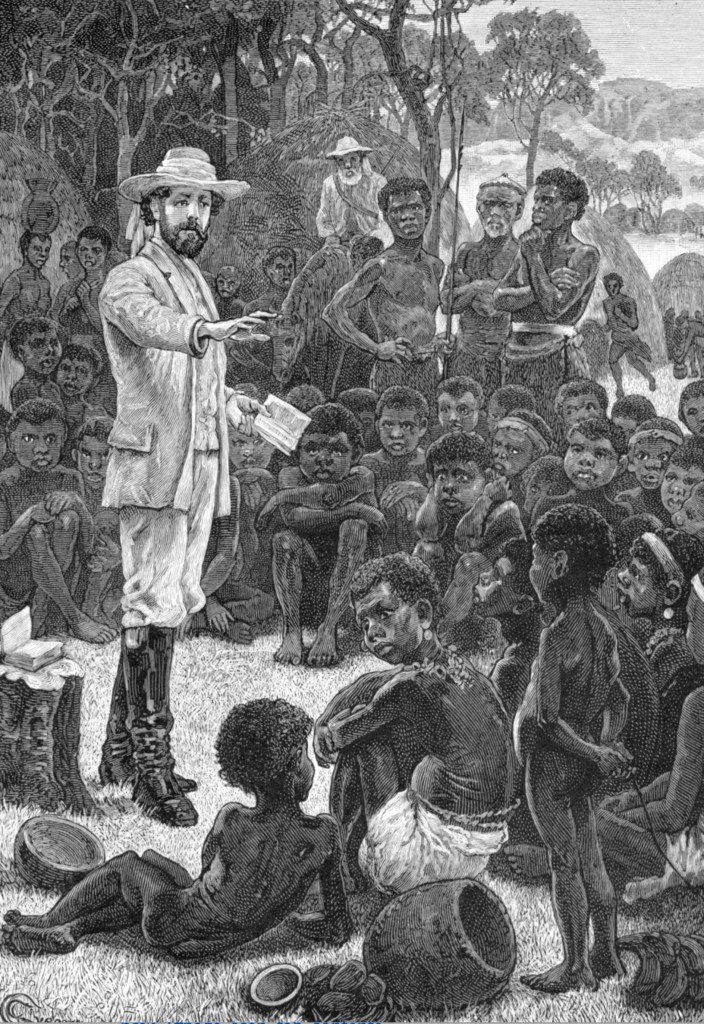

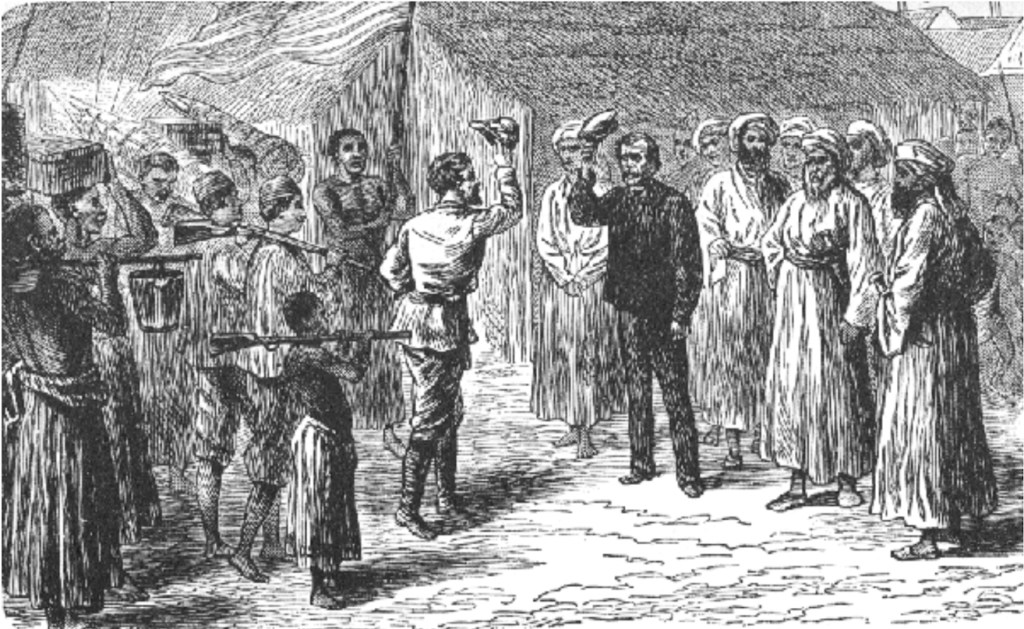

Malawi, or the British Central Africa Protectorate as it then was, did not become a British colony until 1891 but the first British people to travel there with an intent to settle were missionaries and they arrived in the dry season of 1861.

In addition to their leader, Bishop Charles Mackenzie, (left) these first settlers comprised four English men, four black Africans and a Jamaican cook. 1 Mackenzie was guided by David Livingstone who was still in the middle of his disastrous Zambezi expedition and who had no plans to stay in Malawi.

The story of Mackenzie and the ill-fated Magomero mission is told here.

This was the beginning of the colonisation of Malawi. However, before looking at the story of the colonists who came after after Magomero and their fight against slavery I will endeavour to put the occupation of Malawi into the context of what was happening in Africa as a whole and attempt to understand the background to the British colonising the “Warm Heart of Africa”. 2

The Scramble for Africa

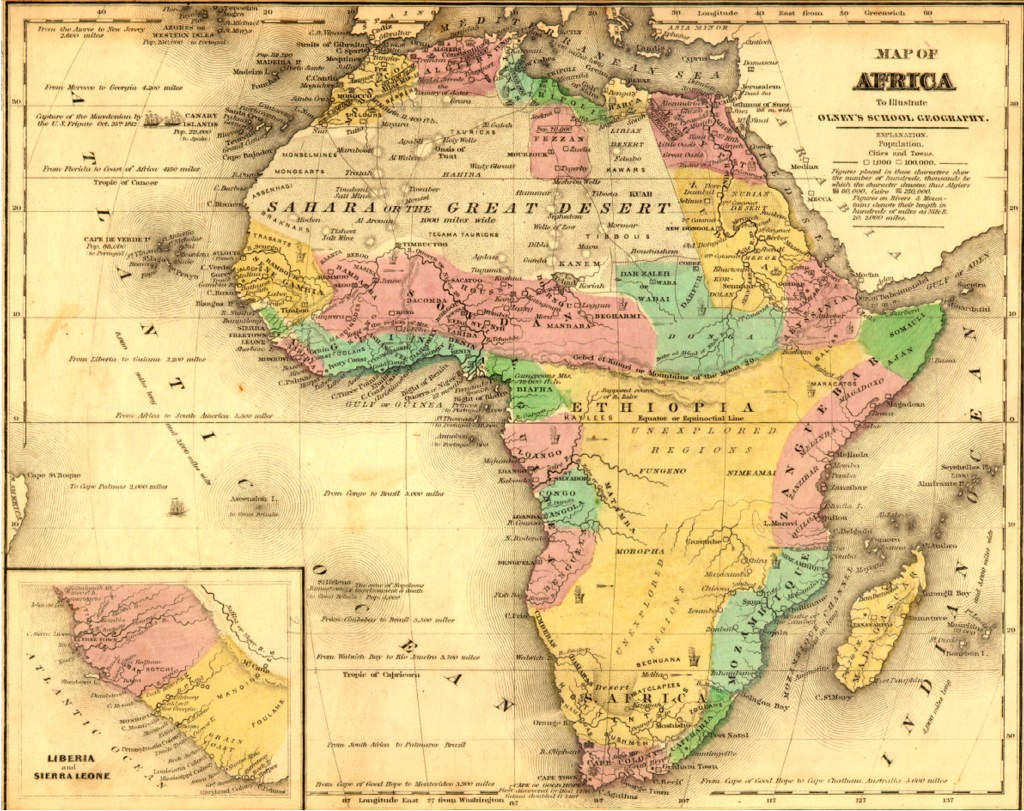

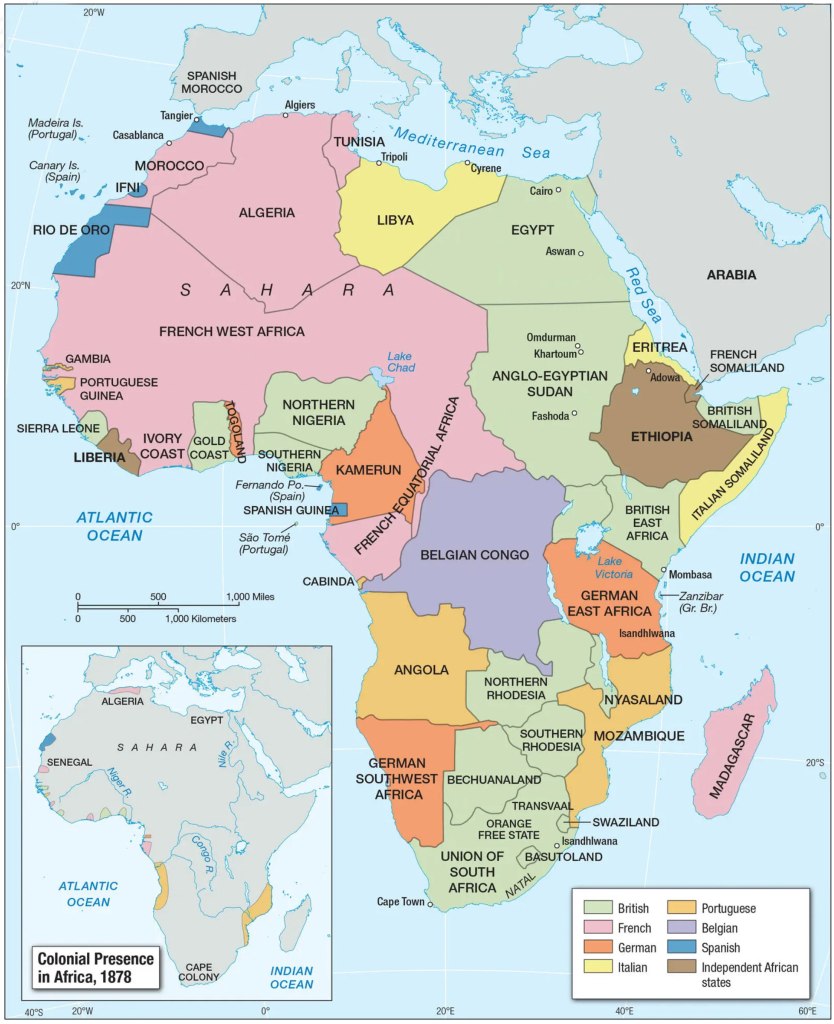

In comparison with the scale of the continent within which it sits Malawi is a small country, a narrow strip of land to the west and south of Africa’s third largest lake which lies mostly within Malawi’s current borders and makes up about 1/4 of the total area of the country. Like many African countries its borders are lines drawn on maps by Europeans:

“As defined by its arbitrarily established boundaries, the territory known successively as the British Central Africa Protectorate, Nyasaland and Malawi, was an artificial construct, one that brought together a variety of peoples equipped with different languages and cultures.” 3

Until half way through the 19th century the British public were blissfully unaware of the people and places in most of the interior of the African continent north of what is now South Africa right up to around 500 kms north of the equator where the map shown above optimistically places the Mountains of the Moon, the legendary source of the River Nile. 4

“Europeans pictured most of the continent as vacant: res nullius 5, a no man’s land. If there were states and rulers, they were African. If there were treasures they were buried in African soil. But beyond the trading posts on the coastal fringe, and strategically important colonies in Algeria and South Africa, Europe saw no reason to intervene. 6

One of the challenges in understanding pre-colonial Africa is that we are conditioned to think that civilisations must follow the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean model that evolved to be our current “Western” society.

A “Civilised Society” is one that develops a writing system, adopts a recognisable form of government, produces a surplus of food and artefacts to enable trade, implements a division of labour and houses its population in urban settlements. Some definitions call for monumental architecture along with significant artistic and intellectual activity.

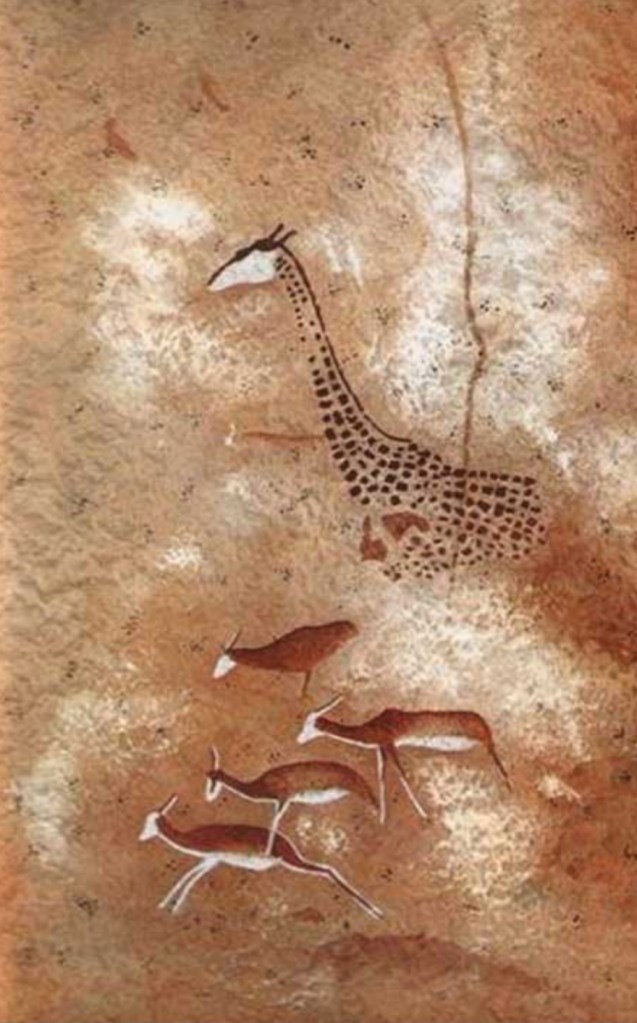

Right: Sophisticated San rock art was considered the work of savages. 7

18th and 19th century Europeans and Americans saw themselves as morally and culturally superior to the rest of the world so Western lawyers involved with international law began to consider what was the “standard of civilisation”; what attributes did your country need to possess to get into the club? In effect they took the Greco-Roman model described above as a starting point and layered on “progress” as another essential ingredient for civilisation.

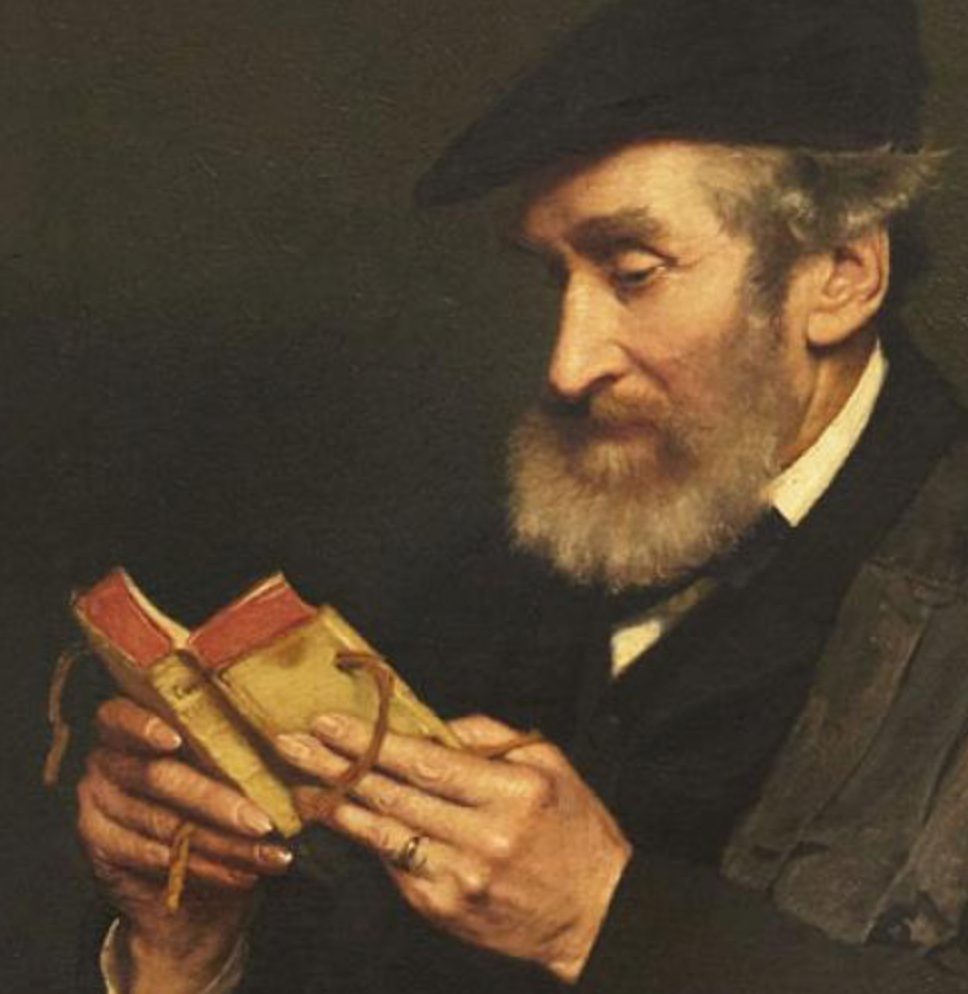

James Lorimer (right), a Scottish philosopher and Professor of Public Law applied the “standard of civilisation” when writing in 1883 that humanity was divided into: “three concentric zones or spheres …….. that of civilised humanity, that of barbarous humanity, and that of savage humanity” 7

The inner circle were the only countries that could be subject to international law. This was inevitably made up of the European powers. Latimer argued that they were:

“state-organised societies governed by the rule of law and committed to protecting fundamental personal liberties.” 7

The middle circle was made up of countries like China and Japan who clearly had complex state-organised societies but their form of governance fell short of European standards, i.e. they governed in a different way to us.

The third circle which, in the 19th century European mind, included most, if not all of Africa, comprised:

“simple peoples that lack any semblance of organised rule and represent humanity in its original condition of savagery.” 8

The concept of being subject to international law was fundamental; if a society had the misfortune to be in the outer circle it had no protection under international law against aggression by a foreign power in the inner circle. It was therefore a breach of international law for Britain to invade France but quite legal to invade pretty much anywhere south of the Sahara and most places north of the Sahara as well.

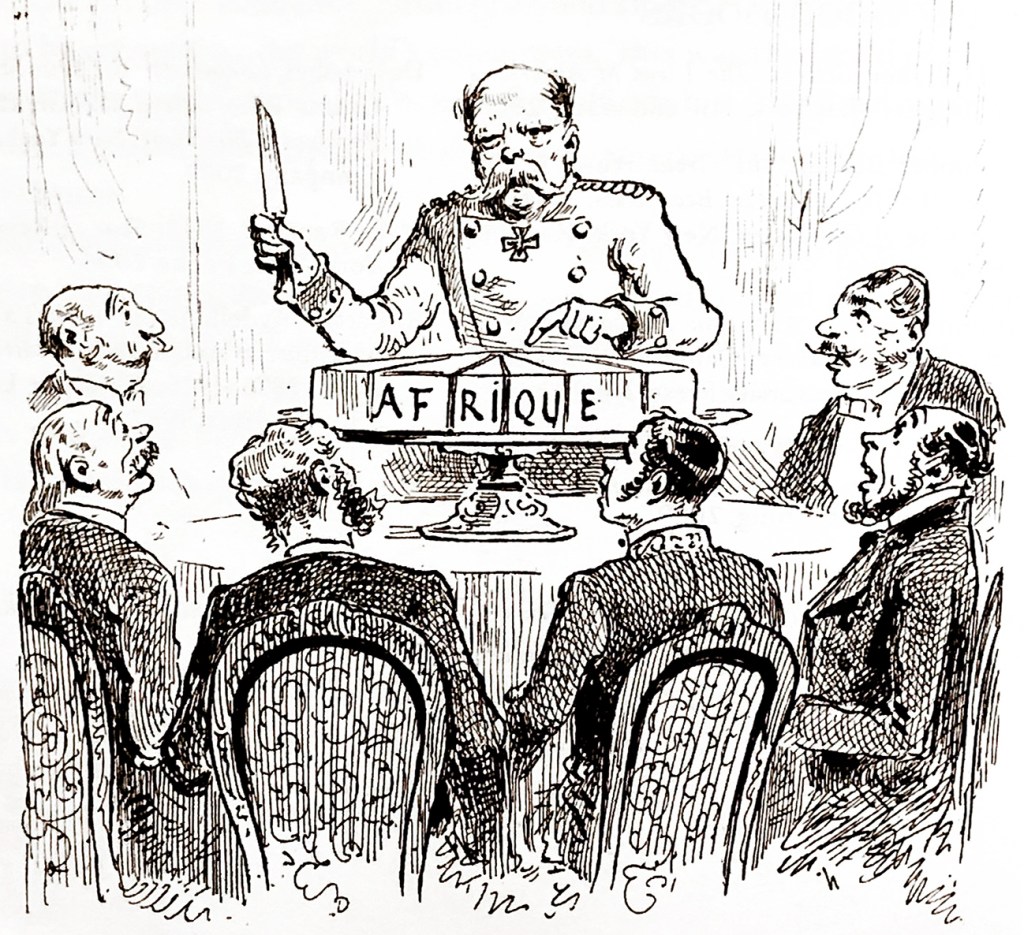

French cartoon originally published in L’illustration in January 1885 9

By including progress in the “standard of civilisation” and by subscribing to the view of international lawyers like Latimer gave the European powers all the excuse they needed to carve up Africa and get on with global expansion in any direction where the could find “simple people” or “savages”. 10

In sub-Saharan Africa the status quo, represented by a few European trading posts and relationships with coastal chiefdoms and kingdoms, lasted until the late 1860s when there were the first signs of mission creep. Britain annexed Basutoland in 1868, the Kimberley diamond fields in 1871, the Boer Republic of the Transvaal in 1877, an act which inevitably led to the Anglo-Boer war of 1880-81, whilst in 1878 belligerent and misguided started the disastrous Zulu War which, after horrific bloodshed on both sides, extended the Cape Colony to the borders of Portuguese Mozambique.

Between 1879 and 1883 France took control of Tunisia, Senegal and Gabon and in 1882 Britain “accidentally” occupied Egypt. Meanwhile Henry Stanley of “Doctor Livingstone I presume” fame had set up a string of trading posts along the Congo River on behalf of King Leopold of Belgium in preparation of Leopold annexing the whole of the Congo as his personal fiefdom.

In 1884 thirteen European countries plus the United States of America met at a conference in Berlin chaired by the Chancellor of Germany and carved up Africa. This triggered the “Scramble for Africa” 11 a unique and dark period in world history that resulted in Ethiopia and Liberia being the only independent states left anywhere on the continent of Africa by the end of the 19th century; today there are 54.

Why?

On reading an early draft of this article a friend asked the simple question: why? Pakenham observes:

Historians are as puzzled now as the politicians were then. …..there is no general explanation acceptable to historians – nor even agreement whether they should be expected to find one. 12

History has a tendency to attribute the initiation of great events to governments but governments are typically, or at least most of the time, finishers not starters.

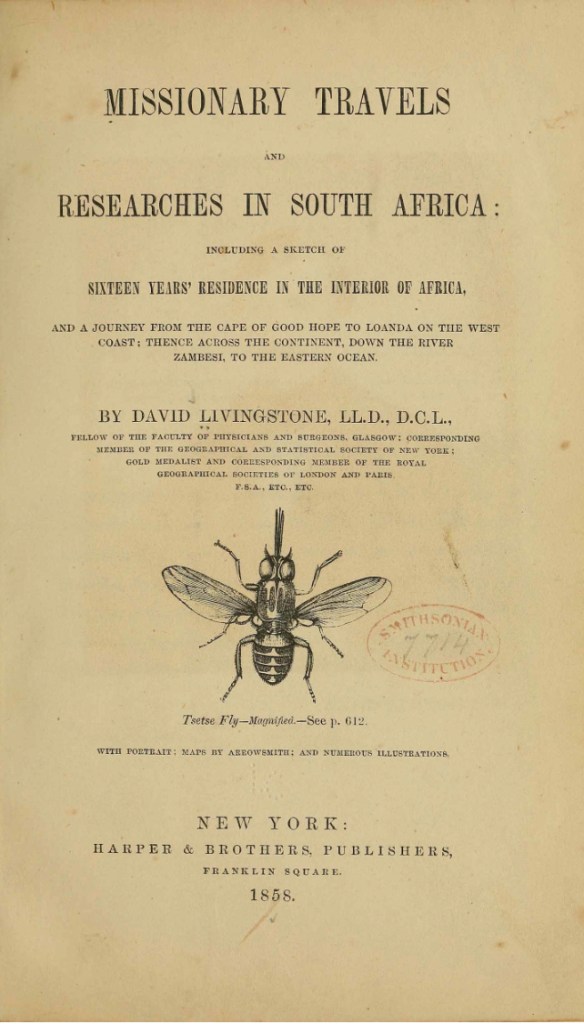

In the second half of the 19th century the British public became increasingly aware of Africa. Tales of exploration and heroic military feats were regularly described in the jingoistic press and many of the explorers and soldiers were themselves prolific writers. Richardson, Livingstone, Burton, Baker, Speke, Grant, and Stanley alone wrote and published twenty-six books between them and dozens more were written about them. The Victorian explorers were the great celebrities of their time; publishers, editors and the explorer authors themselves had a strong vested interest in creating heroes and myths. Henderson argues that their celebrity was driven by the rapid growth in print media with newspapers, magazines and books reaching the masses for the very first time in history. 13

To understand how public opinion supported and in many ways initiated the Scramble it is interesting to look at the influence of David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley who both became best selling authors and who were highly influential in very different ways.

David Livingstone

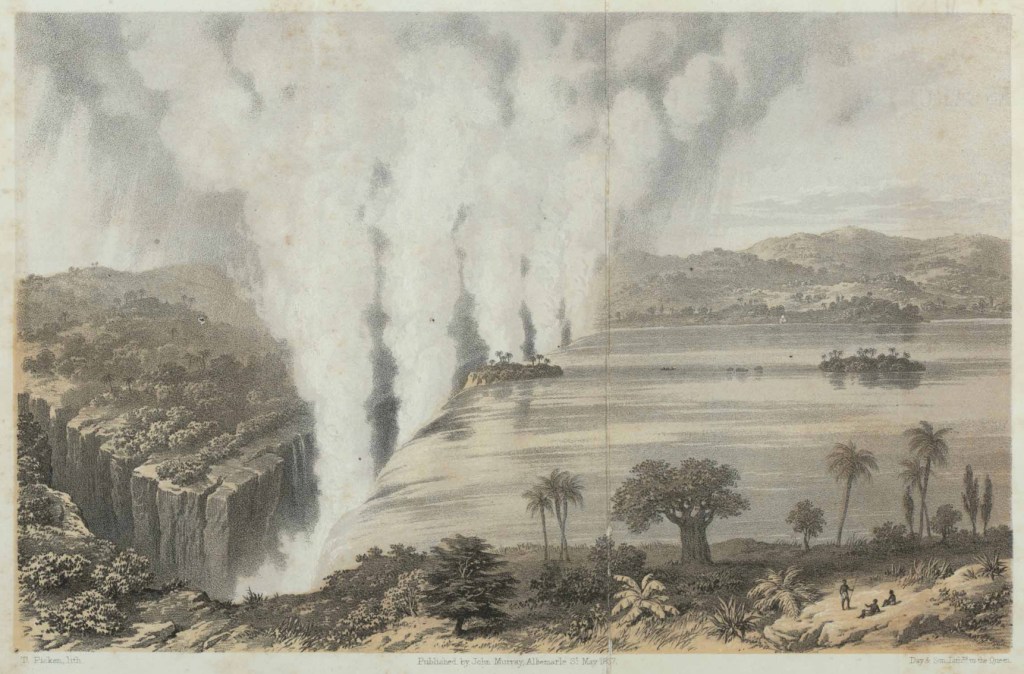

When Livingstone set out on his Zambezi expedition in 1858 he was probably the most famous person in Britain. 14 His first book Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa had sold out before it was even published the previous year.

Livingstone painted a rosy picture of Africa and specifically of the Zambezi and Shire Valleys promoting the opportunity for trade and agriculture but he consistently highlighted that it was a land blighted by the slave trade.

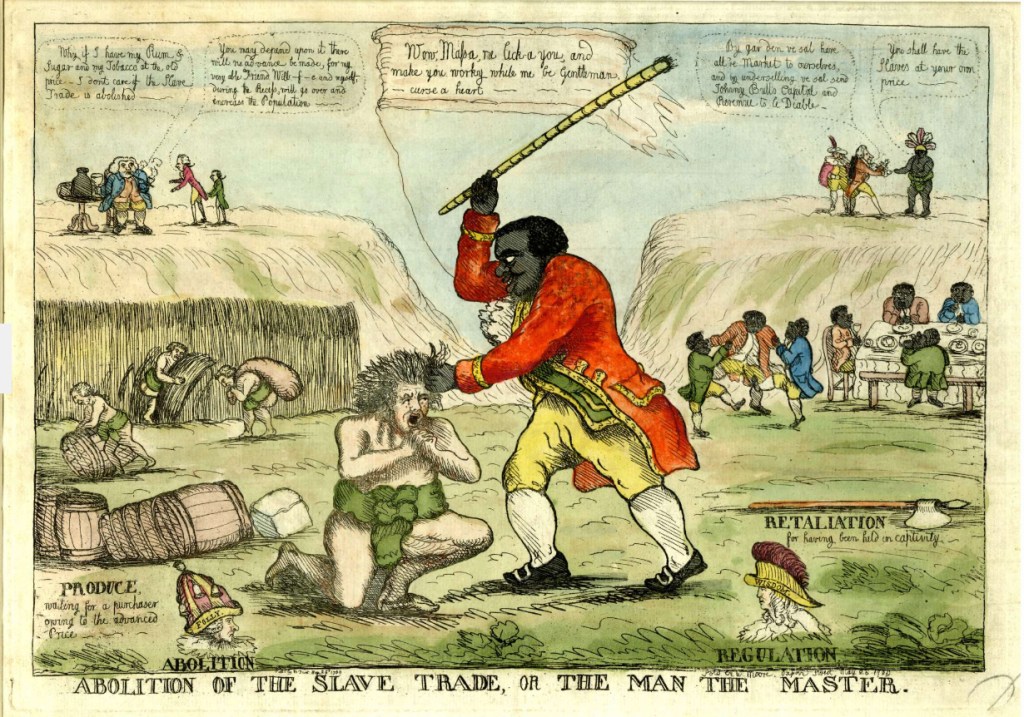

Interest in the abolition of slavery was still very much alive and the British public were dealing with the scandal that they, as a country, had benefited from the trade more than any other nation. They saw the way to address that guilt was to dominate the moral high ground as the first significant country to ban the trade and to take pride in taking direct action to interfere with anyone else still engaged.

The publication of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa presented Africa to Europeans in all its complexity and beauty; rivers teeming with fish, huge herds of elephants and antelopes, baobab trees with 76 foot girths, and ivory left lying on the ground to rot because no traders penetrated the region south of the Zambezi. Livingstone was always intrigued by the people whom he described sympathetically, recording their customs and rituals with, for a missionary, a surprising lack of judgement. However, its publication also alerted the public to the fact that slavery and slave raiding was rife in the African interior.

When Livingstone reached the Makololo on the Chobe River he discovered they were selling slaves to the Portuguese in return for guns and throughout his journeys to and from the mission station at Kolobeng and his epic walk across Africa he witnessed slave hunting and its aftermath time and time again. Closer to home he discovered the Boer farmers near Kolobeng were raiding the indigenous population for slaves:

Throughout his epic walk from

“The Boers know from experience that adult captives may as well be left alone, for escape is so easy in a wild country that no fugitive slave law can come in to operation; they therefore adopt the system of seizing only the youngest children, in order that they may forget their parents and remain in perpetual bondage. I have seen mere infants in their houses repeatedly: this fact was formerly denied.” 15

from Livingstone’s Missionary Travels 1857 16

Livingstone’s answer to finishing the hideous trade in humans was “The Three C’s”, Christianity, commerce and civilisation; he proclaimed the Zambezi river was “God’s Highway” to the interior and on this highway Britain could take his three C’s to Africa.

“In going back to that country my object is to open up traffic along the banks of the Zambezi, and also to preach the Gospel. The natives of Central Africa are very desirous of trading, but their only traffic is at present in slaves, of which the poorer people have an unmitigated horror: it is therefore most desirable to encourage the former principle, and thus open a way for the consumption of free productions, and the introduction of Christianity and commerce.

By encouraging the native propensity for trade, the advantages that might be derived in a commercial point of view are incalculable; nor should we lose sight of the inestimable blessings it is in our power to bestow upon the enlightened African, by giving him the light of Christianity.

Those two pioneers of civilisation – Christianity and commerce should ever be inseparable” 17

Christianity was the cornerstone of his great theory and when he returned from walking across Africa his Cambridge lectures in 1857 were a call to arms for missionaries:

“The end of the geographic fact is but the beginning of the missionary enterprise.”

“I beg to direct your attention to Africa; I know that in a few years I shall be cut off in that country, which is now open; do not let it be shut again! I go back to Africa to make an open path for commerce and Christianity; do you carry out the work which I have begun. I leave it with you!” 18

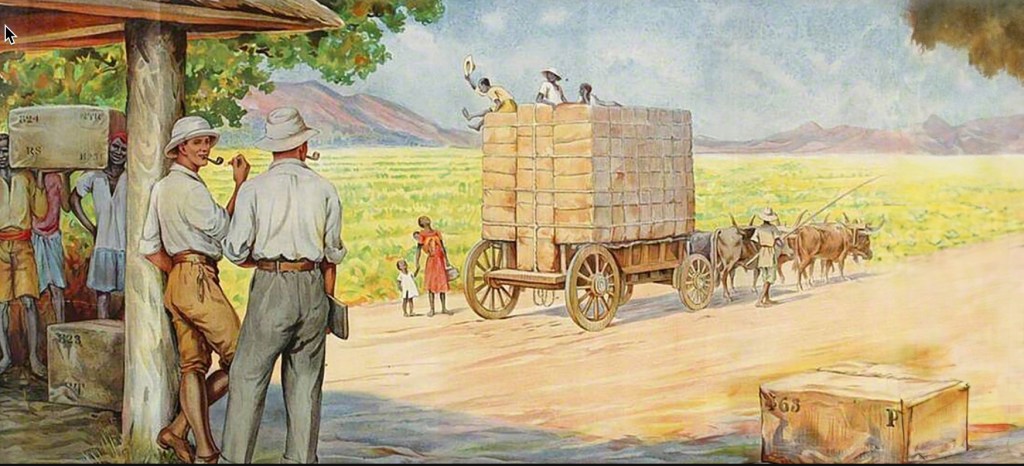

He argued that teaching Africans to exploit their natural resources and engage in long distance trade whilst becoming Christians would be such an attractive proposition that slave raiders would become elephant hunters or farmers and the slave trade would die out. Of course, no one missed the point that Britain would be on the other end of the new trade in ivory, cotton, sugar, indigo and palm oil in exchange for beads, copper wire and cheap Indian cotton.

Livingstone believed that once Christianity and trade were in place good government and thereby civilisation would follow. Livingstone is often criticised as an Imperialist and an initiator of colonisation and if we put him under a 2025 vintage moral spotlight both these labels are true; but, it should not be ignored that he cared deeply for the welfare of African people, called out exploitation and confronted slavers whenever it was possible for him to do so. He never benefited from colonisation and the money he made from his books financed further expeditions to Africa. In his own words:

“In the glow of love which Christianity inspires, I soon resolved to devote my life to the alleviation of human misery.”

Missionaries had been operating in Southern Africa since as early as 1737 19, Ludwig Krapf and his wife Rosina had built a mission station at Mombassa in 1844 and Livingstone himself had walked from the mission station at Kolobeng in Botswana to the Zambezi in 1852. But, his Cambridge lectures inspired a new and significant wave of missionaries to enter the interior of central Africa. Eventually their presence pushed a partially open door wider bringing European traders to the interior which, in turn, inevitably led to colonisation and colonial government.

Henry Morton Stanley

Another complex character who had a significant effect on public option and government policy was Henry Morton Stanley. He was born in Wales in 1841, became an American citizen in 1885 and was re-naturalised as a British subject in 1892. A journalist, adventurer, writer and colonial administrator whose African exploration books became international best sellers. He wrote for the New York Herald and the London Daily Telegraph and became a household name when he found Livingstone at Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in 1871.

November 1871

In 1872 Stanley published his first book “How I Found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures, and Discoveries in Central Africa“, which caught the public imagination in many ways and became an international best seller; the finding of Livingstone was world news and made Stanley instantly famous.

He set off again in 1874 with three British companions and 300 guides, interpreters, cooks and porters; he explored the Lualaba and Congo Rivers and his second best seller Through the Dark Continent published in 1877 showed that the white man could penetrate to the very heart of Africa and the when he got there he would find abundant resources to exploit.

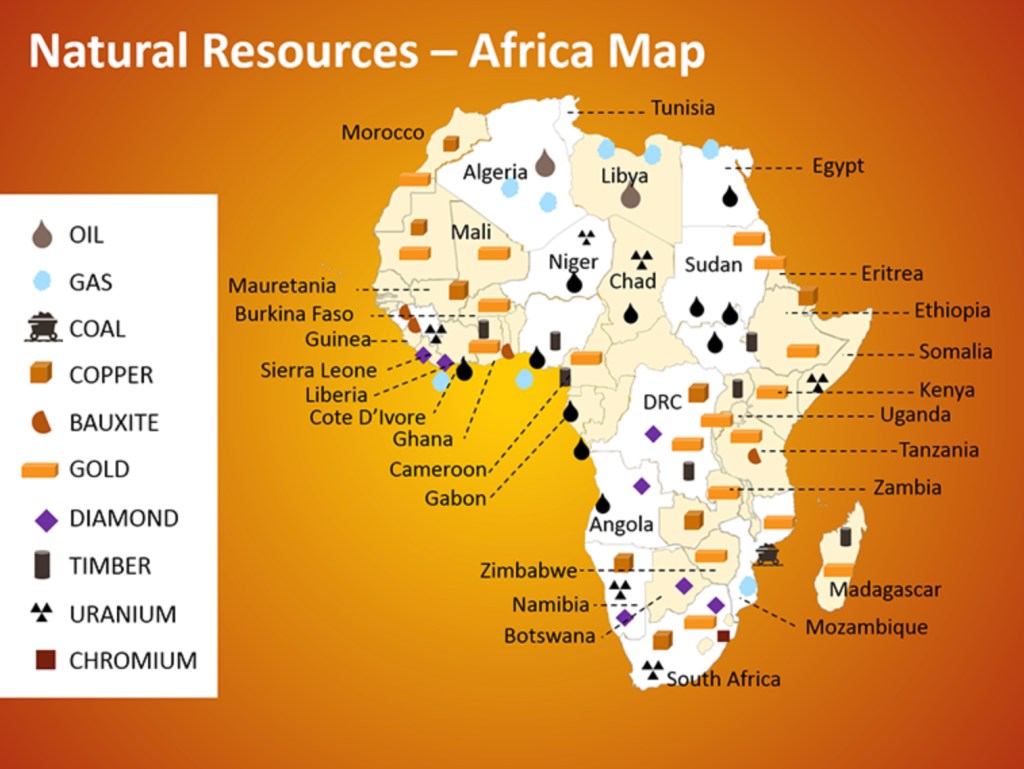

Europeans already knew that Africa was rich in ivory and slaves and there had been some trade in gold and other commodities but in the second half of the 19th century as a result of reports from explorers like Stanley entrepreneurs and governments began to realise that gold, copper, timber, and diamonds were abundant in the south and east and the very places the explorers had discovered were criss-crossed with ancient trade routes. They recognised that the land was not being fully exploited and thought that European farming methods could produce rubber, vegetable oils, sisal, tea, coffee, cotton, sugar and tobacco.

Public Opinion and Attitudes

Livingstone, Stanley and the other 19th century explorers created a myth that here was a beautiful, resource rich, “empty land”, res nullius, that no one owned (meaning no one civilised or better armed than us) crying out for trade and Christianity but still plagued by the slave trade which we, the British, are honour bound to suppress.

Firmly in the mix was a belief in white superiority. How long this had been in the minds of the British is unclear and much debated but the pro-slavery movement, supported by academics, politicians, social writers and scientists had, for a hundred years, fought the abolitionists by dehumanising black Africans arguing that white supremacy was the natural order. “Who else will pick the cotton” summed up the view that there had to be someone labouring on the ground floor of the world economy.

The British Empire had shrunk after the American War of Independence but between then and the “scramble for Africa” it had already grown to include Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, a number of Islands in the Caribbean, Guiana, the Indian sub-continent, Egypt, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, the Cape Colony and lots of islands scattered across the great oceans’ trade routes. It wasn’t so much white supremacy but British supremacy that drove public opinion and politics. The industrial revolution, the fast growing empire and trade with India and China had made Britain wealthy, powerful, arrogant and supremest.

A state of mind evolved in the later part of the 19th century that has some similarities to the idea of “the White Saviour Complex” as first coined by Teju Cole:

“The White Saviour Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege.” 21

The entrepreneurs and traders wanted to get into Africa to exploit her resources; the missionaries wanted to harvest souls and improve the lives of Africans; but improvement mostly entailed replacing African cultures and societal norms with alien systems of worship and behaviour.

Along with the men of the cloth and and wheeler-dealers Africa attracted a motley crowd of hunters, adventurers, colonisers, soldiers and eventually civil servants; many genuinely wanted to save Africa; a mind set summed up by Rudyard Kipling’s 1898 poem:

"Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child."

A strange unsettling poem running to seven clumsy verses that on one hand asks the country to send forth its very best young men to work on behalf of others but consistently paints a picture of the others as ignorant and resistant natives – “half devil and half child”. It warns the men who go to accept “the blame of those ye better / the hate of those ye guard”.

Once European eyes turned towards the African interior invasion and colonisation became competitive; Britain was as concerned with preventing France or Germany claiming huge tracts of Africa as she was interested in claiming more land for herself.

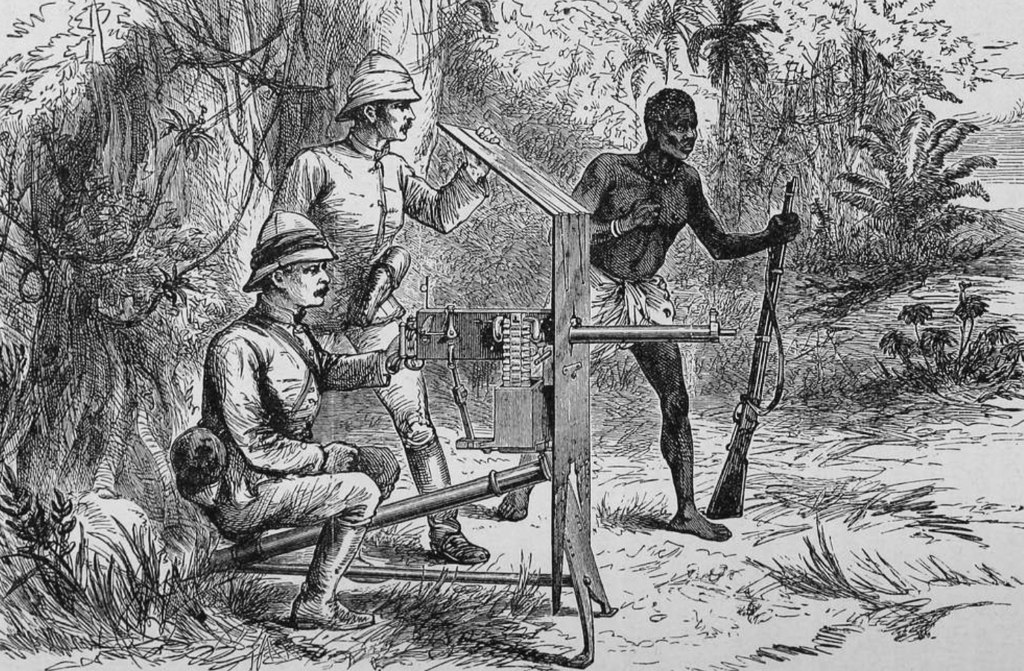

All these strands came together in the closing decades of the 19th century but the weight of public opinion and enthusiasm of individuals to exploit Africa would have come to nothing if not for one final factor:

“Whatever happens, we have got, The Maxim Gun, and they have not.” 22

Europeans were well armed with the latest military hardware and, often highly organised; great advances had been made in the prevention of malaria and Africa was no longer “the white man’s grave“. 23 There was nothing to stop the scramble to rape Africa.

The Myth of the Empty Land, res nullius

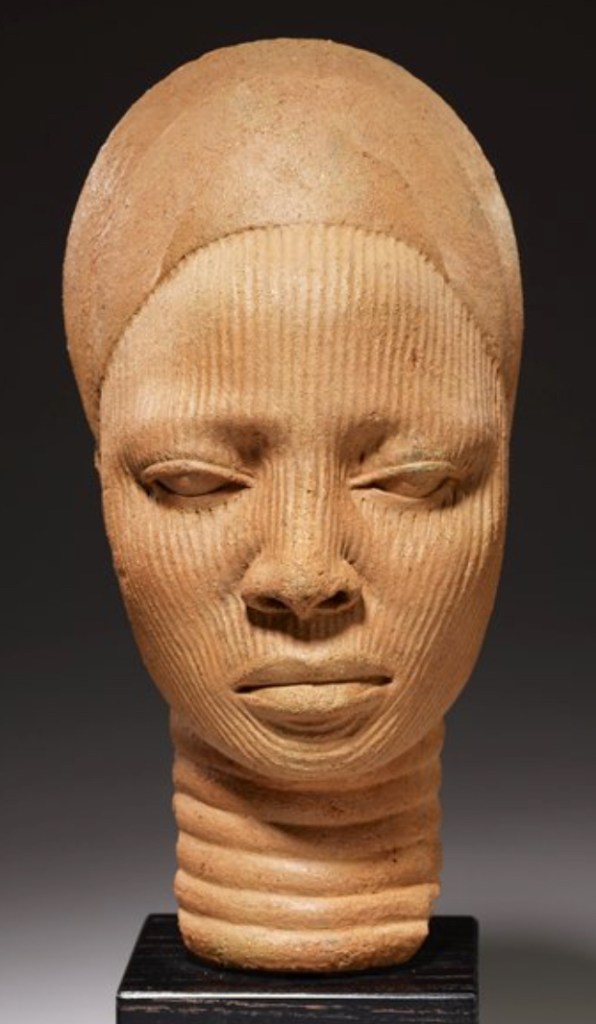

Kingdoms and Empires

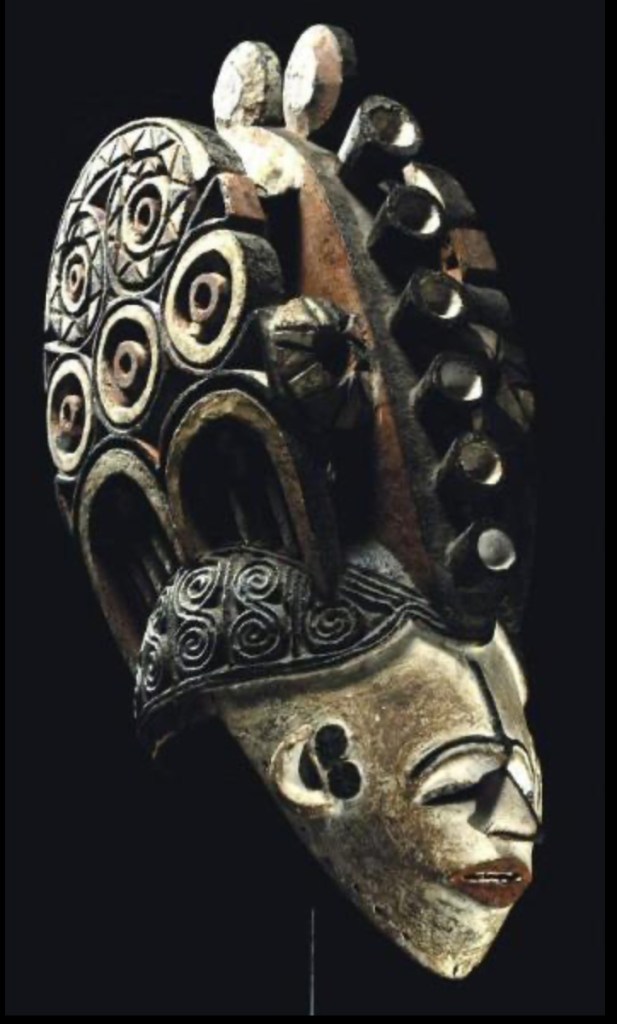

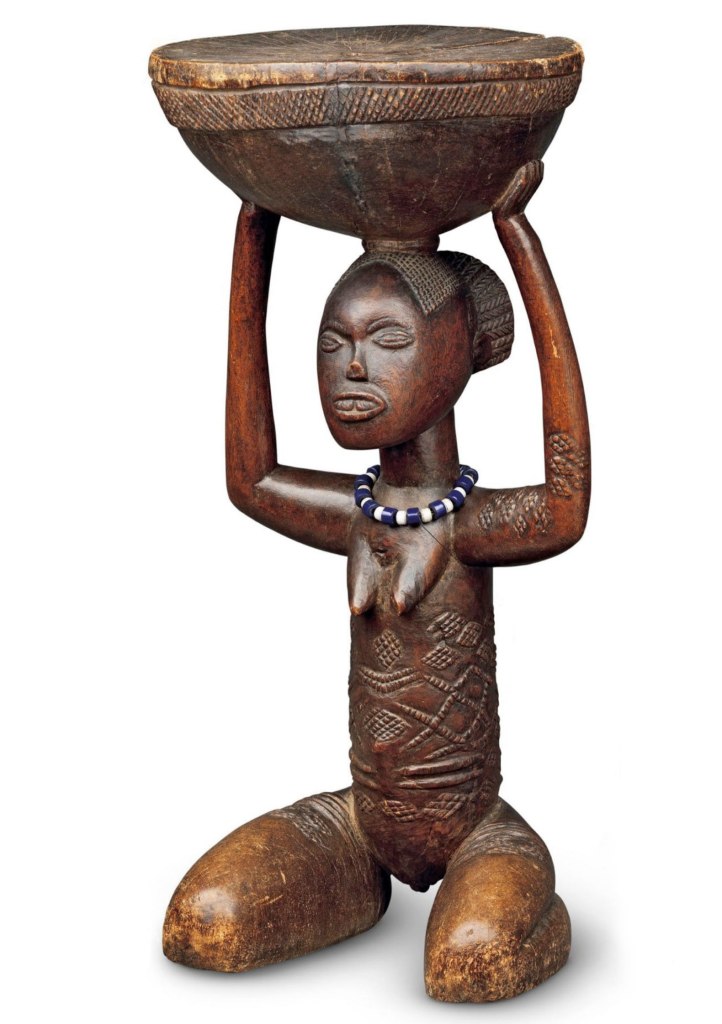

Regardless of the motivations of governments and individuals on the ground at different times during the colonial era, and the colonists’ motivations varied enormously, the scramble for Africa was an invasion, an incursion by a large number of well armed people into places that did not belong to them justified by the idea that Africa was an empty land, res nullius, belonging to nobody. The European mind could not conceive that successful societies with unique cultures could exist on the “dark continent” 25; a vibrant continent that is home to 3,000 ethic groups and 2,000 languages.

Europeans and Americans considered Africa as being inherently backward and uncivilised; until comparatively recently historians rejected any suggestion that sophisticated societies existed south of the Sahara. In 1969 Hugh Trevor-Roper, a professor of history at Oxford University said:

“Perhaps in the future there will be some African history to teach. But at present, there is none; only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness.”

There is still convenient conventions of describing Ancient Egypt as an offshoot of societies that had developed in Mesopotamia or that the Nile Valley was originally settled by people coming from the Levant.

Christopher Ehret, a professor of African history and African historical linguistics, is very clear, or as he puts it is “beyond reasonable doubt” that all the linguistic and cultural evidence shows that the Nile Valley was settled by people arriving from the Horn of Africa in the centuries preceding 15,000 BC. 27 It is beyond the scope of this essay to consider all the evidence Ehret presents but the fundamental point is that Egypt is not only in Africa but is and always has been African.

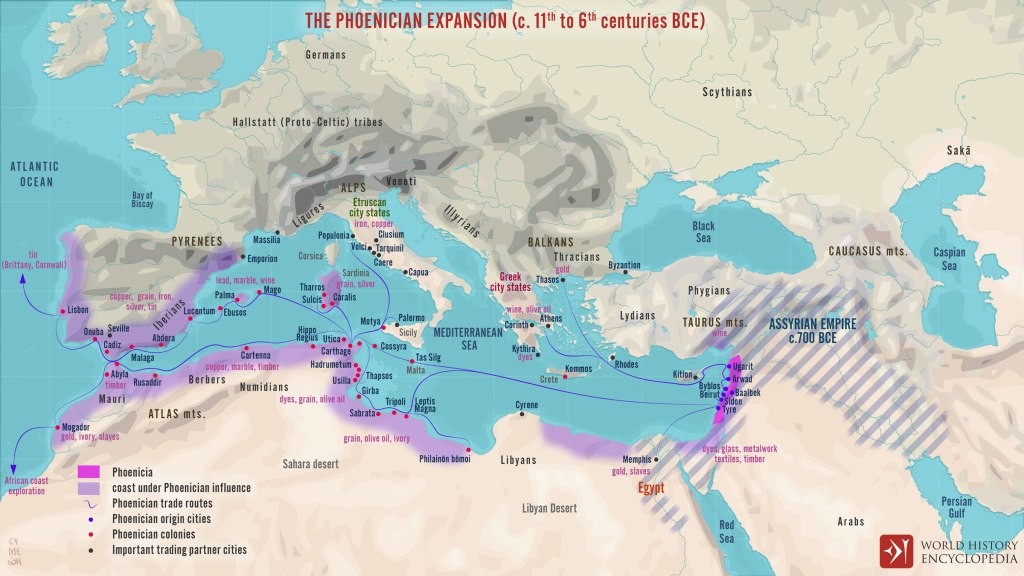

The Phoenicians who were a Semitic society, akin to the Hebrews, developed as one of the earliest Mediterranean trading nations along the coast of the Levant. In around 814 BC they founded Carthage to the west of Egypt in modern day Tunisia.

Carthage became independent of Tyre and became a city state in its own right about the time when Tyre was defeated by the Babylonians in the 6th century BC.

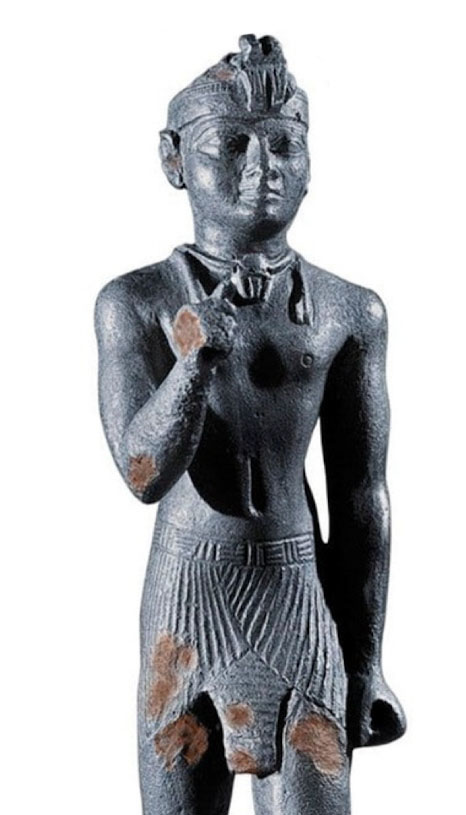

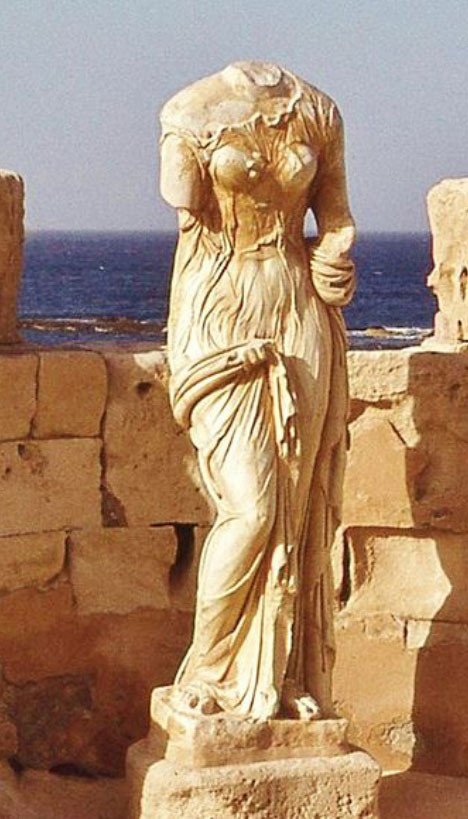

Above: Carthaginian God.

Carthage was built on African soil, a city that in its day surpassed Athens and Rome for its scale and influence. Ethnically it was a mixture of Phoenician, Berber and Lybian peoples and it stood on the coast of Tripoli until destroyed by the Roman Republic in 146 BC, a period of 668 years. Many historians describe Carthage as Phoenician which is like describing New York as Dutch or Warwick as French. 28

Carthage was an African empire.

If we look at the great span of known history from the days of ancient Egypt until the European colonisers invaded the continent many African empires, kingdoms and distinct cultural groups rose and fell.

Some of those societies are shown below; some organised themselves in way that would meet the Eurocentric definition of civilisation and others had very a different perspective on how a society should operate.

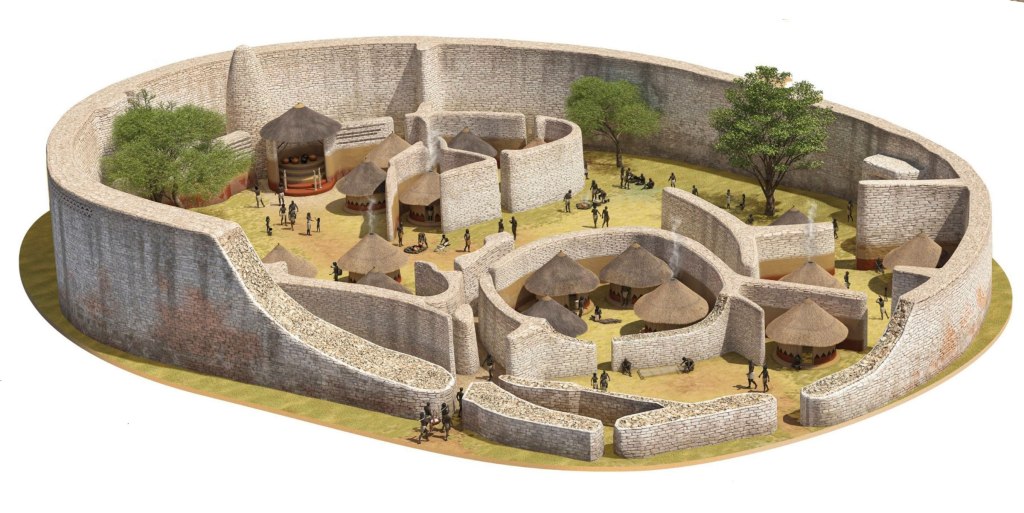

Great Zimbabwe is the largest of over 150 major stone ruins left across modern day Zimbabwe and Mozambique by the Shona people whose Mutapa Empire thrived from the 15th to 17th centuries.

When Europeans found the ruins of Great Zimbabwe in the 19th century they were quick to attribute it to a lost race of white people or to Phoenicians, Yemeni and Arabs. Just about anyone other than the Bantu who were still living there. For more on the Europeans and Great Zimbabwe see Appendix B.

Industry

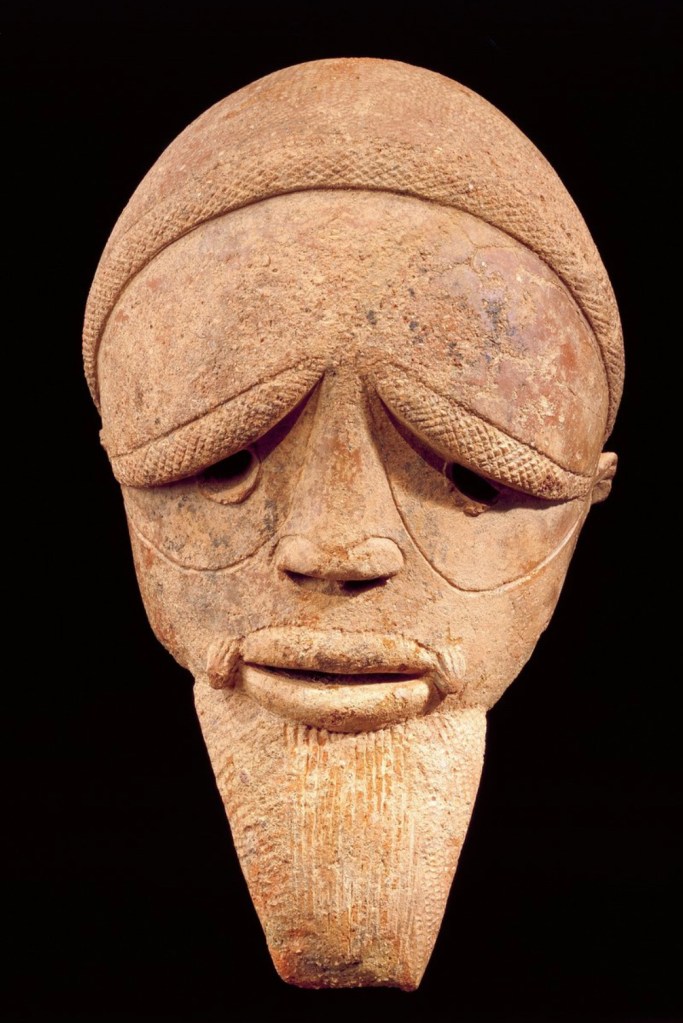

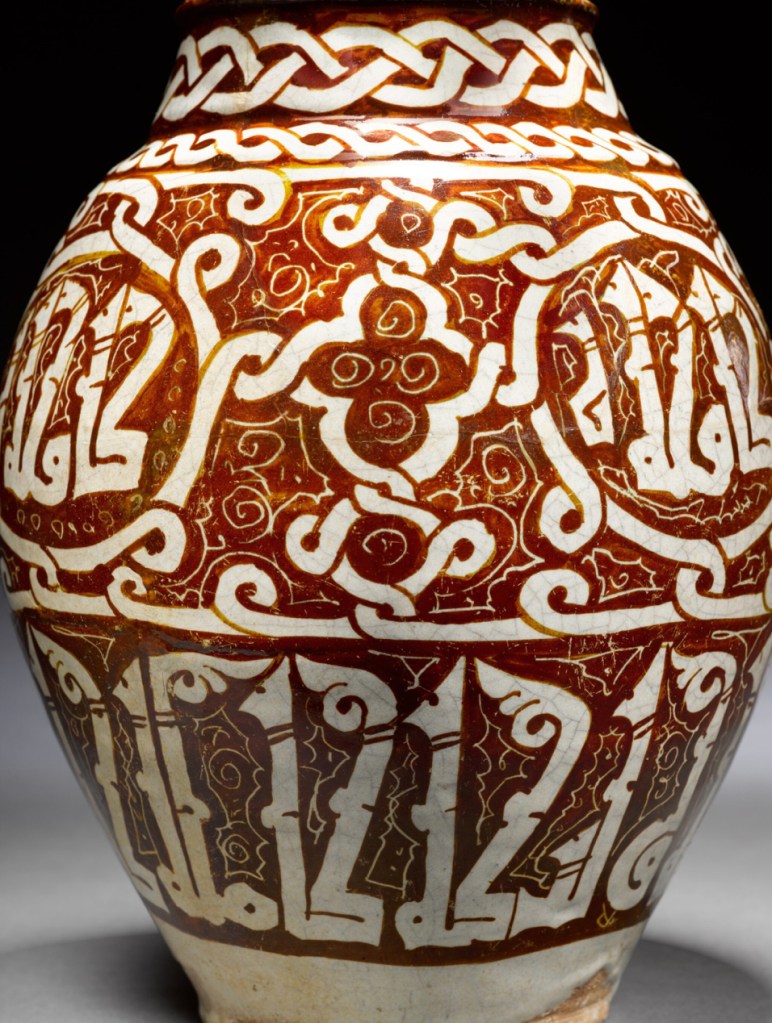

Ceramics

For thousands of years Africans kept pace with, and at times, were at the forefront of technological and agricultural innovation. Pyrotechnology, the use of heat to change the chemical structure of something found in the ground, is one of humankind’s most important discoveries. As early as 9,500 BC, at least 3,000 years before the technology was first used in the Middle East or Europe, people in Mali and soon afterwards people in the Sudan were firing pottery.

Observations of the long-standing tradition of female potters in contemporary African cultures suggests women discovered the technology of making and firing pottery and, in Africa, the craft has remained predominantly, and in ancient times exclusively, practiced by women. 30 Its discovery had a far reaching effect on diet, cooking, food storage and trade and is likely to have led to the discovery of metallurgy, another pyrotechnology. 31

Ironworking

When ironworking was first practiced in Anatolia it evolved at the end of a long progression of technologies from stone to copper, then bronze and finally to learning the skills and building furnaces capable of smelting iron sometime between 1800 and 1500 BC. However, south of the Sahara metallurgists at sites such as Oboui in the Central African Republic, the earliest known iron-working facility anywhere in the world, progressed directly from stone to simultaneously working iron and copper as early as 2200 BC and only later started working bronze and gold.

The African iron smelters were highly innovative and appear to have continually tinkered with their furnace designs to address the different types of iron ore found across Africa. Very tall natural draft furnaces as much as 7 metres high were being used in some locations and the extremely high temperatures these furnaces produced resulted in people living in the Great Lakes region making carbon steel directly from the initial smelt by the year 1 AD; a remarkable 2,000 years before Europeans learnt how to make steel in a single process.

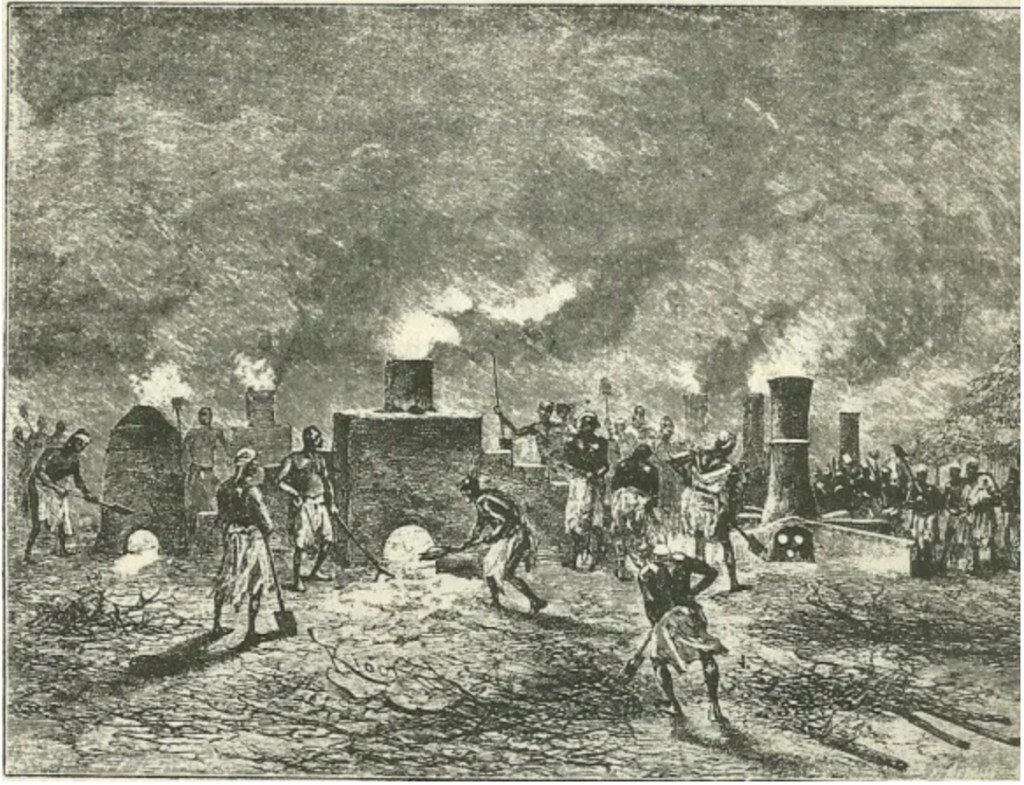

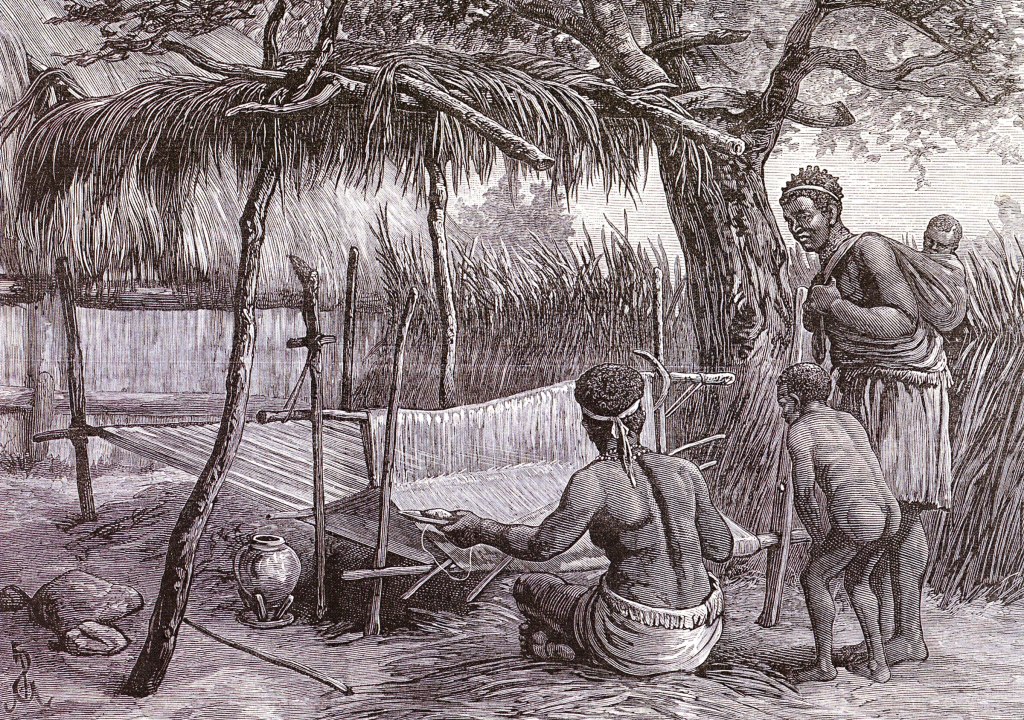

Illustration by Louis Binger ca. 1892 34

From as early as 1,000 AD the output from African smithies achieved industrial scale. Based on the analysis of slag heaps archeologists are able to calculate the manufacturing output of ironworks at different sites. Drogon smiths in south-central Mali have left evidence of slag equating to the production of 26 tonnes of iron objects a year and at Korsimoro in Burkina Faso 32 tonnes a year. 35 By the year 100 AD iron works were operating across the whole continent from the mediterranean coast to Matola in Mozambique and Silver Leaves near the Balule Game Reserve in South Africa. 36

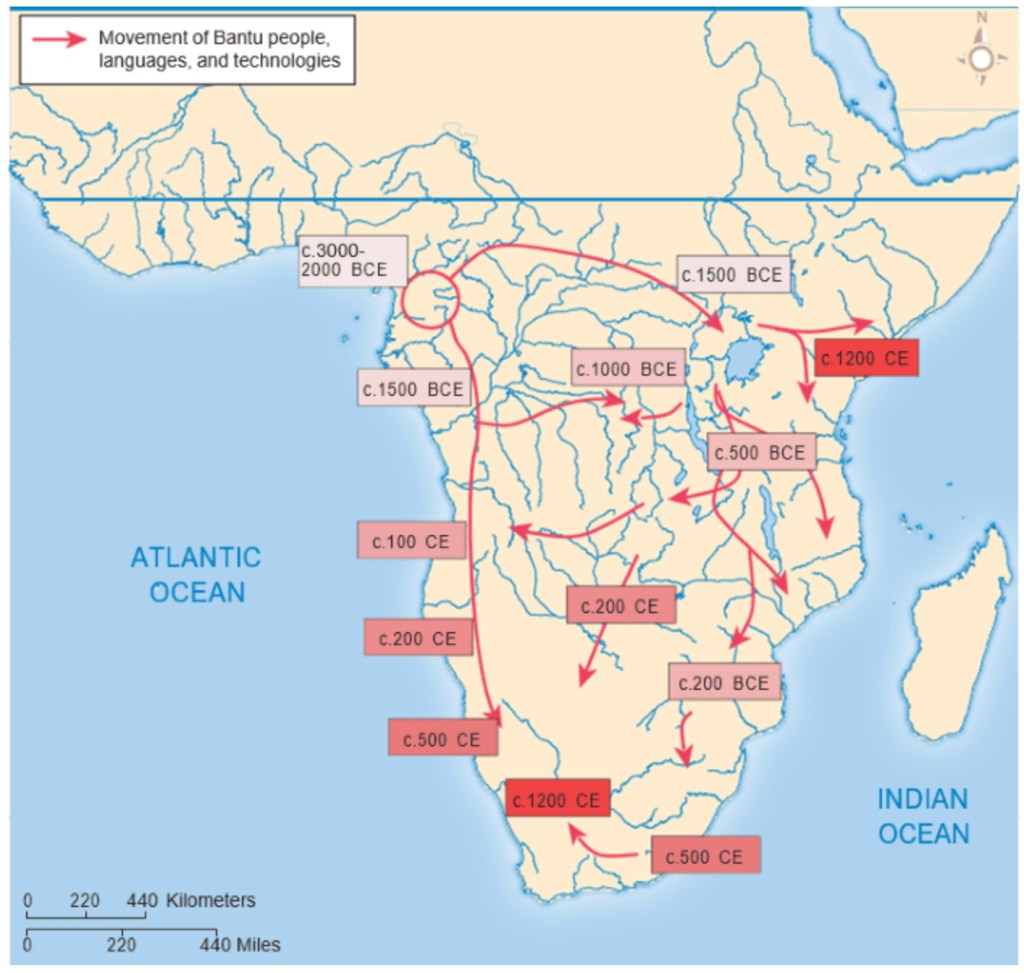

1500 BCE (BC) to 500 CE (AD) 37

Ironworking facilitated the migration of peoples, the spread of agriculture and the creation of kingdoms. People speaking Bantu languages began migrating out of West Africa as early as 1500 BC equipped with iron tools and weapons. They probably moved in small groups and the pace of their spread across equatorial Africa was slow as they cleared new areas for agriculture. They met hunter gather groups who were dispersed or absorbed but the hunter gathers knew how to survive in each particular environment and this knowledge passed to the Bantu as their skills in ironworking and ceramics spread to the hunter gathers.

By around 300 BC the Bantu had reached the Great Lakes area where they met other skilled ironworkers moving south from the Sudan, these people were more advanced and sophisticated farmers and as knowledge flowed between them they merged and formed new groupings that travelled south and west. By 300 to 400 AD Bantu-speaking people with their accumulated skills in ironworking, ceramics and agriculture lived in nearly all of Africa south of the Sahara.

In a separate development Khoisan people of the Middle Stone Age were mining red haematite (red ochre) and specularite (sparkling ores) from 43,000 until 23,000 BC in the oldest know mine in the world at Ngwenya, Eswatini. The San people living in Eswatini were using the red ochre to create the many rock paintings that can still be seen in Eswatini. By 400 AD Bantu people had reached the area and began to extract iron ore from a second mine on the site.

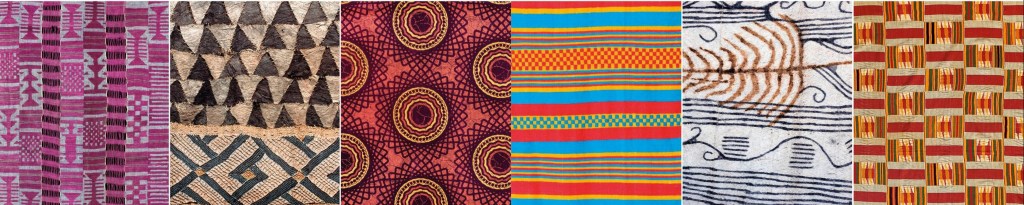

Textiles

The technology of weaving cotton into cloth was independently invented in different parts of world but ceramic spindle whorls found in a neolithic site near Khartoum dating to between 6000 and 5000 BC suggest that the first cotton weavers anywhere in the world were Africans living in what is now Sudan processing Gossypium herbaceum, commonly known as Levant Cotton, which is native to Africa. 39

By the second millennium BC cotton textile making had spread to west Africa where the tradition of weaving cloth in long strips and sewing it together to make a garment was developed.

Left: Ghanaian Kente cloth which follows the ancient tradition. 40

The West Africans also invented a unique form of loom weaving to produce raffia cloth and it was this technology that the Bantu people took with them as they migrated across Africa. 41 Variations in materials, techniques and designs evolved in different parts of Africa and many of those styles have survived hundreds, if not thousands of years and are still used to express ethnicity, status or association with a particular political party.

Pre-Colonial Industry in Malawi

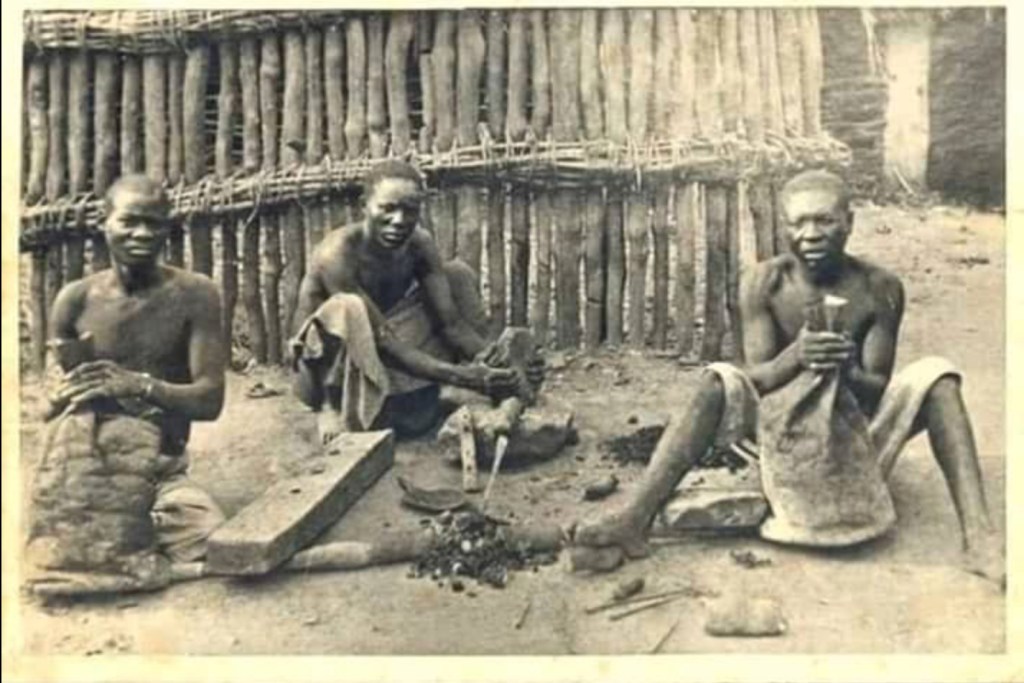

David Livingstone was the first European to document Malawian life inside pre-colonial villages and goes into some detail regarding the industrial activity.

“The Manganja are an industrious race; and in addition to working in iron, cotton, and basket-making, they cultivate the soil extensively.

Iron ore is dug out of the hills, and its manufacture is the staple trade of the southern highlands. Each village has its smelting-house, its charcoal-burners, and blacksmiths. They make good axes, spears, needles, arrowheads, bracelets and anklets, which, considering the entire absence of machinery, are sold at surprisingly low rates; a hoe over two pounds in weight is exchanged for calico of about the value of fourpence.

In villages near Lake Shirwa and elsewhere, the inhabitants enter pretty largely into the manufacture of crockery, or pottery, making by hand all sorts of cooking, water, and grain pots, which they ornament with plumbago found in the hills.” 42

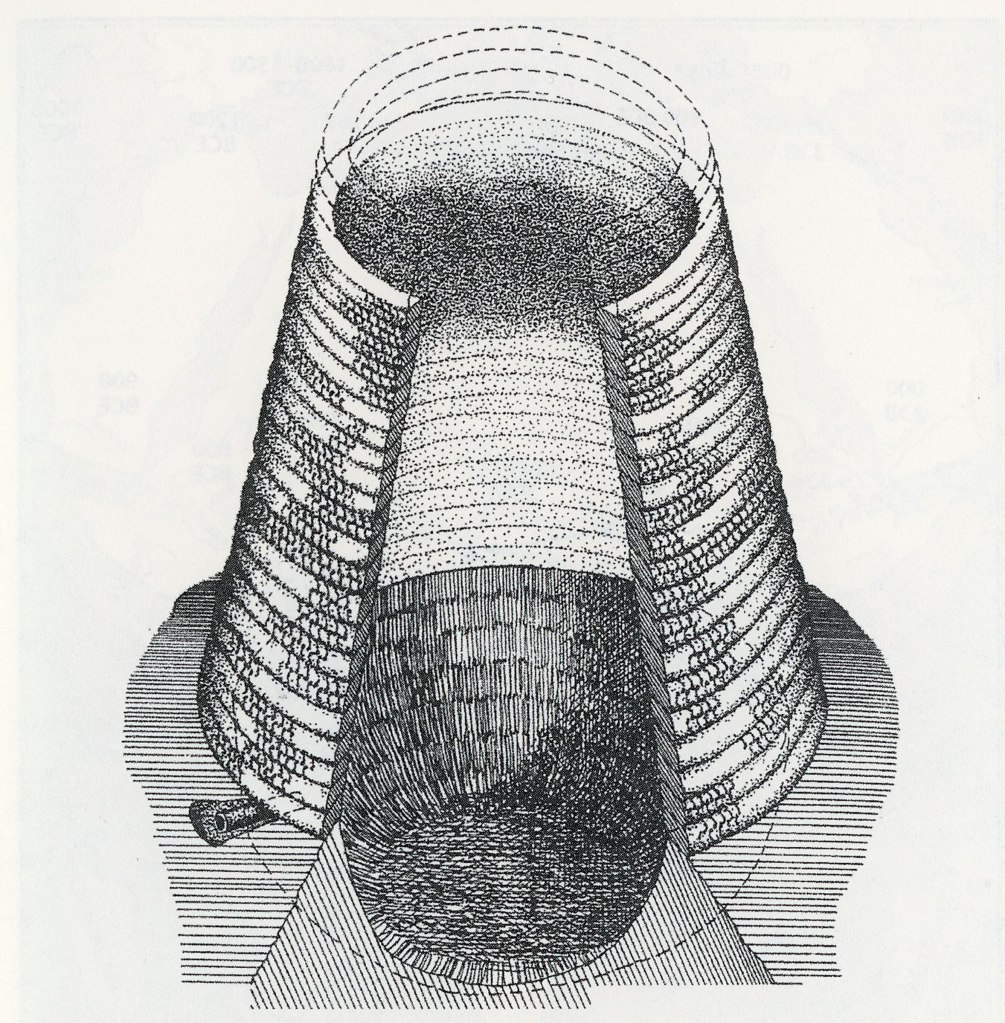

Iron was being smelted in Malawi from at least as early as 300 AD and by the time Livingstone arrived it had evolved to be a highly sophisticated but uniquely African process. Smelting was undertaken in the dry season; men selected a site to build the kiln away from their village but near a water source and a termite mound. The termite mound potentially served two purposes: as a high place away from predators to sit and watch the kiln and as a source of clay with which to build it. The men made charcoal, collected iron ore and fired the kiln which had to be watched and fed for two to three days. The iron bloom was collected and cut into smaller pieces to be worked by the village blacksmiths.

The process was surrounded by ritual, women were not allowed near the kiln and the ironworkers had to refrain from sleeping with their wives whilst the iron was being smelted. Virgin fire, made by twisting a twig on a prepared board, was used to light the kiln and beer was brewed and offered to the ancestors along with prayers. 43

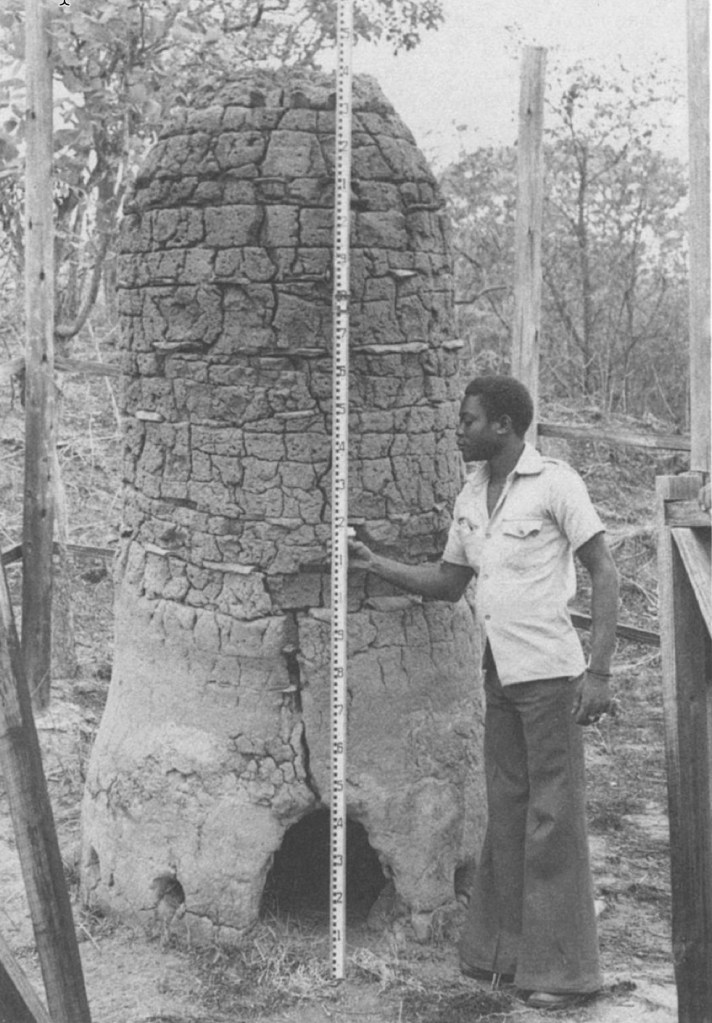

A bloomery furnace (see right) near Kasungu, Malawi.

The stack is made of baked clay taken from termite mounds and is sufficiently high to permit the furnace to attain smelting temperature by natural draft rather than with an air blast provided by pumping bellows.

The bloom was removed through the large opening when smelting was finished. 44

Sadly the British discouraged iron working when they declared Malawi a protectorate in 1891:

“(In) 1921 the last worker on iron smelting, the father of village headman Vijumo, was arrested and posted to work at a metal products company in Blantyre, after serving a sentence.” 45

Africans were weaving cotton into cloth 2,000 years before the technology was discovered in either India or South America. Specialist loom weavers were working in the towns of present day Mali by around 1000 BC and it is notable that the skills of cotton weaving and iron smelting were well established among the Bantu population of West Africa and the Nilo Saharan people in the east before these groups began to colonise east and central Africa. As these migrations moved south the technologies moved with them.

Loom weaving is an highly skilled process but it is obviously dependant on the farmer cultivating and harvesting cotton and to do that he or she had to find the right right mix of soil, climate and access to water, growing conditions that could be found in the Lower Shire Valley. Livingstone was excited to find cotton growing here as he worked his way north in 1859.

“Cotton is cultivated at almost every village. Three varieties of cotton have been found in the country, namely, two foreign and one native.

…. Every family of any importance owns a cotton patch which, from the entire absence of weeds, seemed to be carefully cultivated. Most were small, none seen on this journey exceeding half an acre; but on the former trip some were observed of more than twice that size.

The “tonjé cadja,” or indigenous cotton, is of shorter staple, and feels in the hand like wool. …… Everywhere we met with it, and scarcely ever entered a village without finding a number of men cleaning, spinning, and weaving.

It is first carefully separated from the seed by the fingers, or by an iron roller, on a little block of wood, and rove out into long soft bands without twist. Then it receives its first twist on the spindle, and becomes about the thickness of coarse candlewick; after being taken off and wound into a large ball, it is given the final hard twist, and spun into a firm cop on the spindle again: all the processes being painfully slow. 47

In the colonial era Albert Duly 48, a customs officer, described the type of small holdings that had probably existed well before Livingstone tramped across them:

“(The Malawian farmer) grows bananas, mangoes and other fruit. He cultivates sorghum, bulrush and other kinds of millet, maize, cotton, rice, groundnuts, beans, peas, sesame and cassava. In his dumb gardens he grows sweet potatoes, pumpkins, beans and a late crop of Maize.” 49

He went on to describe the thoughts of one farmer:

“Many of us are skilled in choosing the right plots for particular crops. We judge not only by the nature of the soil itself but by the grass which may be growing on it. Mphumbu soil will produce a good crop of bulrush millet, ncecha, a light sandy soil, is the best type for groundnuts. Ndrongo, a black soil, is ideal for cotton. Nsangalabwe, while not suited to most crops, is very favourable for maere (finger millet), used in brewing best beer.” 50

Iron production was more common in the highlands where cotton could not be grown so iron tools made their way down to the Shire Valley in exchange for cotton cloth. Because, as Livingstone noted, preparing cotton and weaving cloth was a “painfully slow” process, the final product was highly valued as a trade commodity.

Salt was another important industry with women in control of both small and large scale production. It was another lowland industry and important as a trading commodity with people living in the highlands and into eastern Zambia where it was exchanged for hoes, goats and cloth.

“There was also a lively trade with the inhabitants of the Chilwa basin, an area where, because of low rainfall and poor soils, agriculture was a particularly hazardous business. the people of lake Chilwa thus relied on trading their fish, and the high-quality salt they produced, for foodstuffs from other areas.” 51

As Livingstone remarked:

“The Manganja are an industrious race.” 52

Trade

Intra-African Trade

The chariot is being drawn by two horses 53

Trade, the peaceful exchange of things, swapping what I have and you need for something you have but I need, appears to be a human activity that potentially predates homo sapiens by about 100,000 years. Archeologists working in Kenya have found 300,000 year old lumps of pigment, “crayons”, that were typically used by early humans to decorate or otherwise mark their bodies. The pigment was not local to the site where it was found and in the same excavation archeologists have found stone tools made from materials that could not have been locally sourced.

Scientists interpret these finds as evidence of early long distance trade routes although we cannot know, or even guess what these early humans gave in exchange for these commodities. 54

There is the possibility, based on ancient rock art, that long distance trade routes were operating across the Sahara as long as 10,000 years ago; more than 500 drawings of chariots have been found between the Fezzan in Libya and northern Mali and then west to the Atlantic coast. The Fezzan sat on busy trade routes that saw salt, cloth, beads and metal goods heading south in exchange for gold, ivory and slaves coming north. 55

It is unlikely that chariots drawn by horses were travelling across the Sahara but the humble donkey was first domesticated in Africa as early as 5000 BC and was the first animal used to carry loads and, in the Middle East, to pull carts thus facilitating long distance trade. 56

The output from ironworks at several sites across Africa went far beyond any local needs strongly suggesting these smithies were trading iron, tools, knives, machetes, harpoons and weapons. In turn the spread of machetes, metal hoes and ploughs dramatically increased agricultural output and created surpluses that could also be traded.

We know that copper working had developed in parallel with ironworking and that this led to working gold and bronze stimulating trade in raw materials including the tin needed to make bronze and trade in the finished products.

As soon as humans discovered salt could be used to preserve meat it was always in demand everywhere away from the coast or salt lakes. Such was its importance that trade routes in salt are some of the earliest recorded worldwide and cultures went to war to control the source of salt.

In the 3rd millennium BC villages and small towns began to develop at Dhar Tichitt in the southwest corner of the Sahara desert in what is now Mauritania. From 3000 BC to 1000 BC the western Sahara was far more humid than it is today and the people settling here could grow millet, herd cattle, sheep and goats, hunt, fish and gather food from plants. 58

Tichitt developed as an organised society which, in 1600 to 1000 BC, featured drystone walled family compounds clustered in groups of between 20 and 200 compounds across nearly 100 separate settlements and a large proto-urban centre at Dakhet el Atrous with a population approaching 10,000 people. 59 It appears that specialisation had developed very early in some of these settlements with, for example, one village produced arrow heads and another grindstones. There was active trading not just between the settlements but with people living hundreds of kilometres away. 60

The Turin Papyrus Map was discovered in a private tomb near the Valley of the Kings at Luxor, it shows a gold mining complex complete with a water reservoir, housing and a temple to Amun around 100 kilometres to the east of Luxor at Wadi Hammamat. Along with the gold mines that were operated from 1500 BC until 600 AD the map locates quarries that are known to have been worked from 3000 BC to 400 BC for a sought after and rare ornamental stone. 61

Trade inside ancient Egypt was controlled by the pharaohs but the Cult of Amun owned huge tracts of land so the existence of a temple to Amun at the gold mines may not be coincidental and suggests the intriguing possibility that the cult mined gold to sell to the pharaohs’ tomb builders or for export beyond the borders of Egypt.

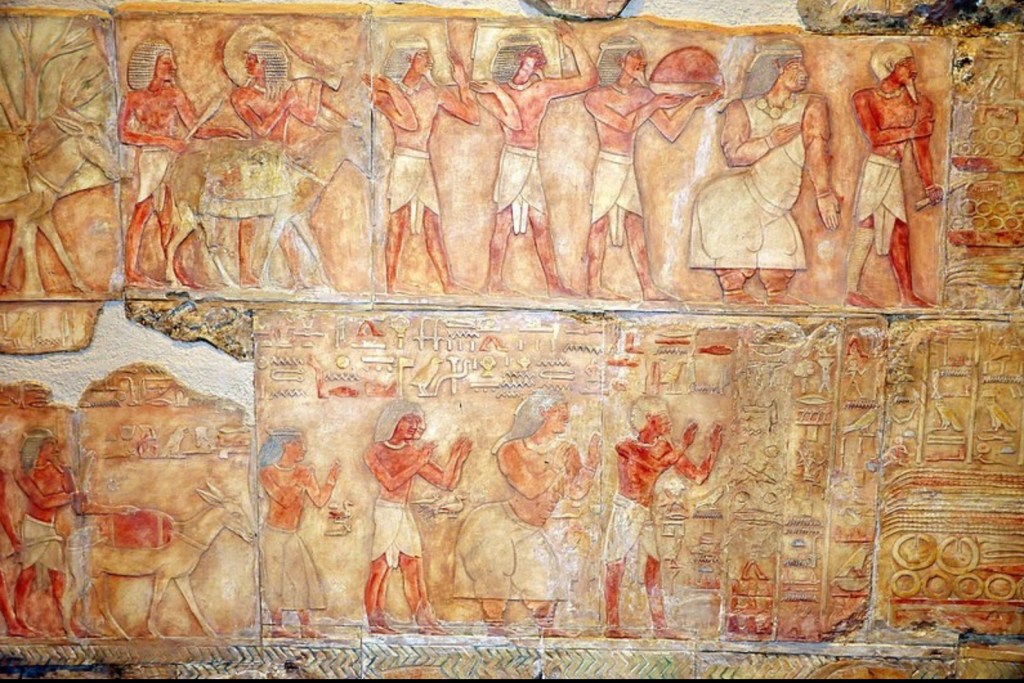

From as early as 2700 BC Egypt was establishing caravan routes that would continue to be used into modern times to import gold, ivory, ebony, spices, animals and plants from Nubia. Around 1500 BC Queen Hatsheput despatched expeditions to Punt in the Horn of Africa to trade for Myrrh and this trading relationship evolved to provide Egypt with slaves, myrrh, frankincense, resins, and exotic animals like baboons and giraffes. 63

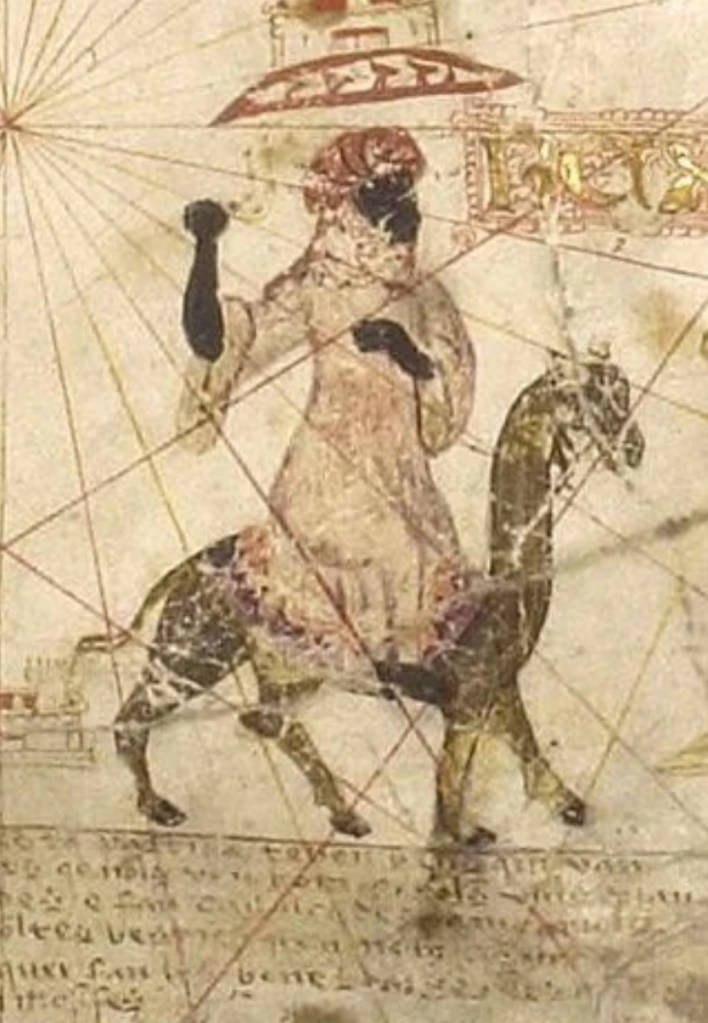

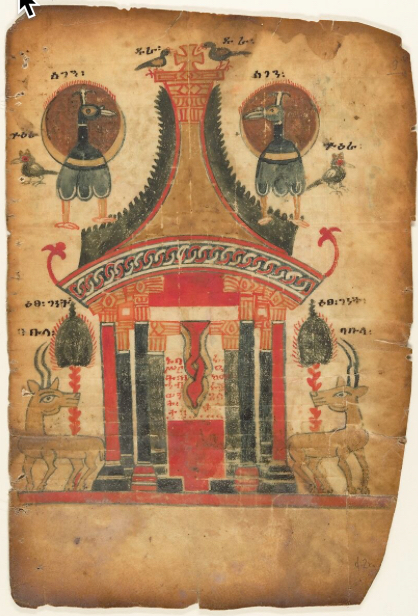

Later, in the 1st century AD the Kingdom of Askum in modern day Ethiopia flourished as a trading hub exporting ivory, tortoise shells, gold and emeralds; some of these commodities were locally sourced but some suggest trade links to the African south. Tantalisingly we know about a wide range of trade goods at the extremities of east and north eastern Africa but very little evidence how these commodities reached the coastal entrepôts or trading hubs such as Askum.

Large slag heaps attest to the industrial scale production of iron at Meroe in Kush as well as at the production sites previously mentioned in south central Mali and Burkina Faso dating from as early as 1,000 BC. Iron itself as well as iron tools and weapons were being traded south to the Great Lakes Region perhaps by the Bantu People and their newfound neighbours from the Sudan who, as they migrated and colonised south through the continent, probably established trade routes back to West Africa and north to the Nile Valley.

It is clear that very early in Africa’s history ceramics, textiles, iron and ironware, copper, gold, tin and salt were being produced, extracted or processed in quantities that exceeded local needs. These products along with ivory, precious stones and ebony were being traded. Archeological and rare documentary evidence provides some insight into the trade of these non agricultural products across long distances and there must have been localised trade of commodities such as grain and cattle. 65 Taken as a whole this suggests top down organisation and the emergence of a merchant class, local traders and markets.

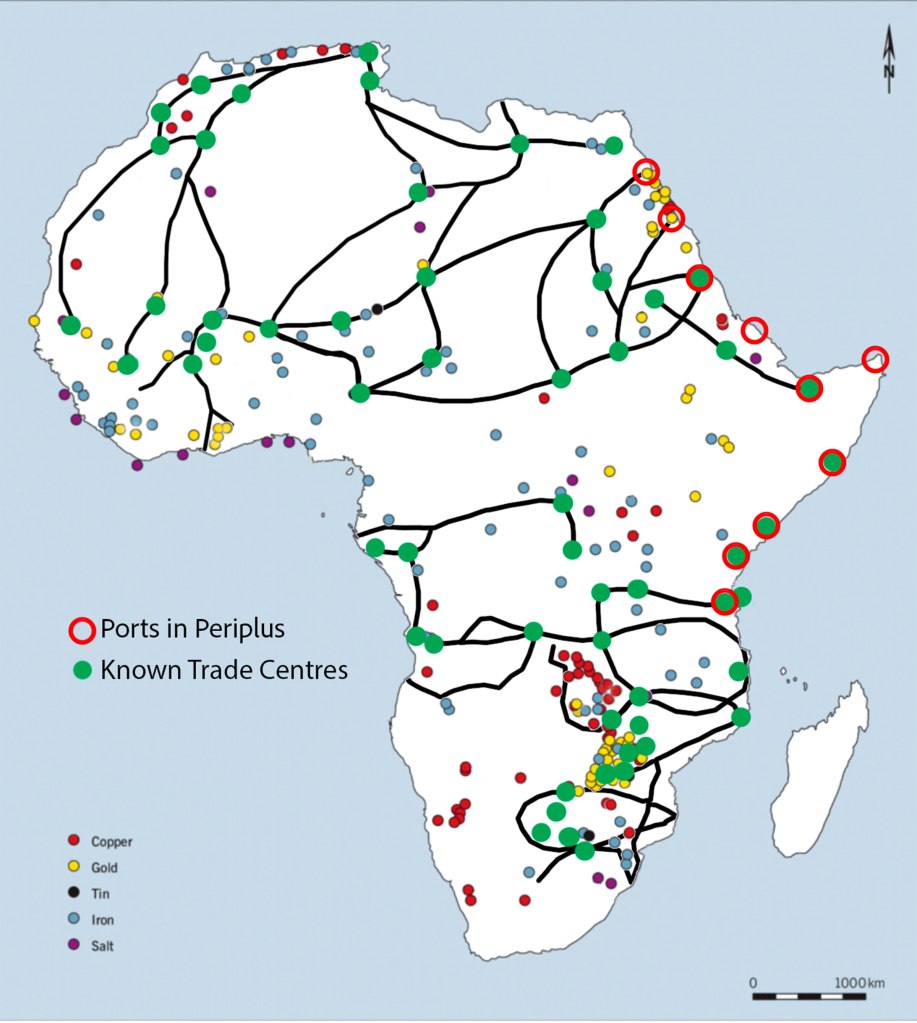

Based on Shadreck Chirrikure. 66

The map shown above gives some idea of the extent of known trade routes within pre-colonial Africa and the main sources of metals and salt. It excludes many commodities that were extensively traded from very early times. These include Ethiopian obsidian which was being traded 70,000 years ago and evidence that hunter gatherers were trading ostrich eggshell beads, animal skins and meat with pastoral communities on the KwaZulu Natal coast 10,000 years ago.

Shadreck Chirikure believes:

“This shows that trade and exchange constitute one of the most established cultural behaviours attested in the African past.” 67

Having reviewed several sources it is clear that the list of commodities being traded from widespread and organised African societies from the Neolithic until the Medieval era is as multifarious as a comparative list of traded commodities for the same timescales in Europe. It is likely that the categories were similar: foodstuffs, textiles, ceramics, metals, metal tools and weapons, metal ornaments, salt, spices and scented gums, skins and ivory.

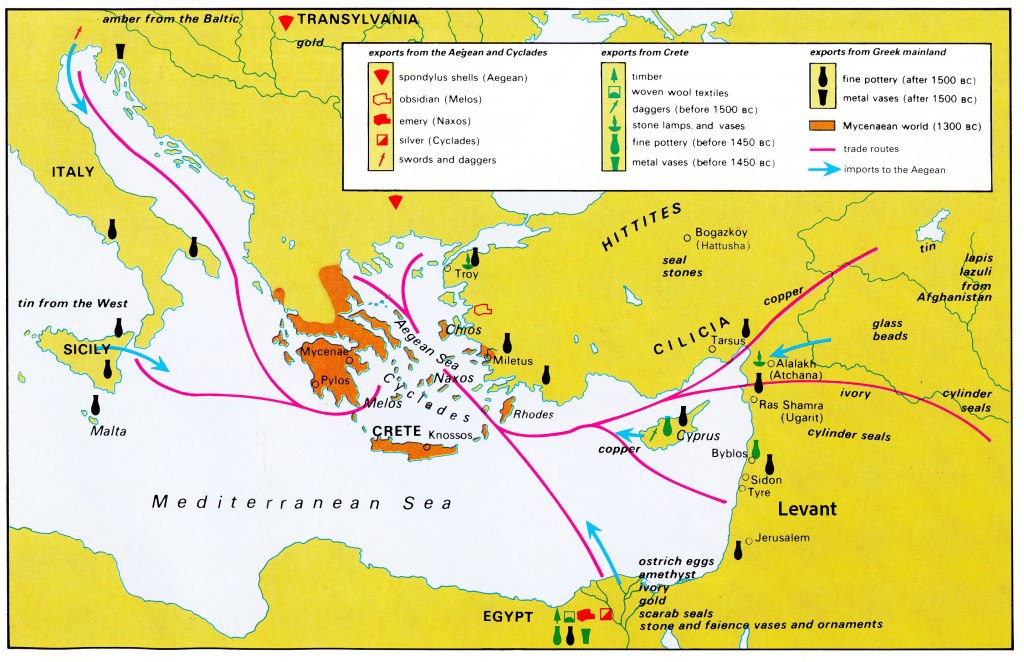

The Emergence of Intercontinental Trade

From around 3000 BC the Egyptians were exporting gold, precious stones and textiles to Canaan in the Levant and gold to Mesopotamia and in exchange were importing copper, turquoise, pottery, wood and fish from Canaan and grain, knife handles and cylinder seals from Mesopotamia. This was accompanied by an exchange of ideas with the Canaanites adopting Egyptian burial practices, worshipping the goddess Hathor and copying pottery styles while Egyptian culture was strongly influenced by ideas from Sumer. 68

Minoans & Canaanites

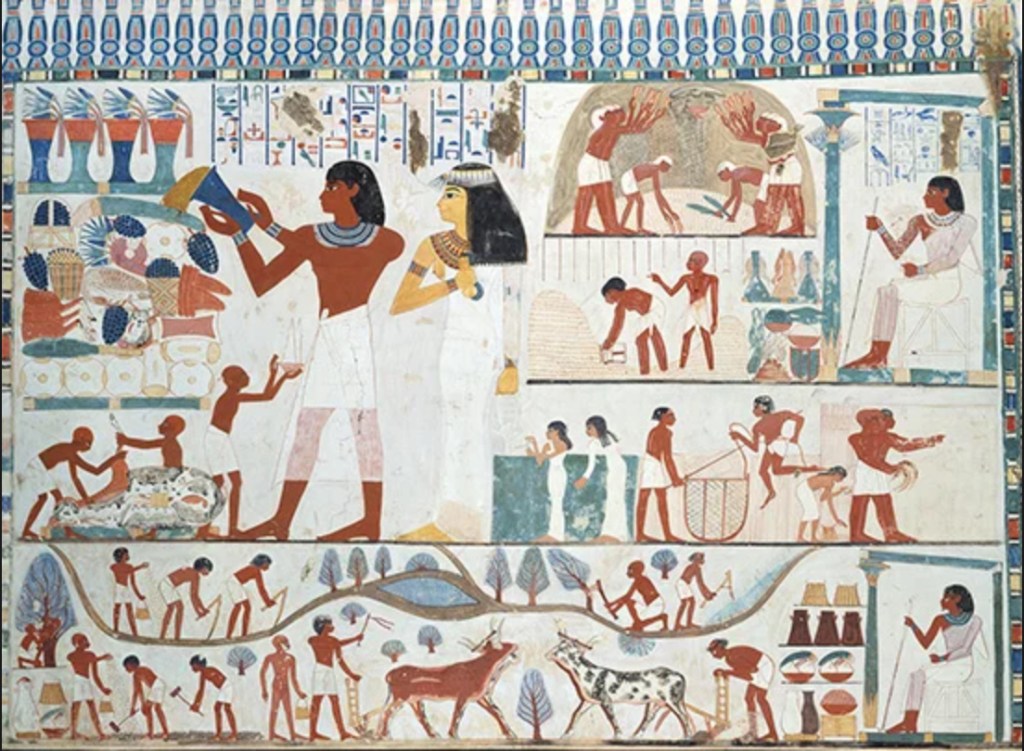

Egyptian hunting cat from the tomb of Nebamun c. 1350 BC. The cats appear to have been used to retrieve game. 69

By 1500 BC the Minoans appeared on the scene and became the dominant trading power in the eastern mediterranean exporting olive oil, pottery, wool and timber to Egypt in return for ivory, gold, dates, hunting cats, linen, papyrus and alabaster. Once again there is evidence that trade was never just about the exchnage of commodities in these early societies with Egyptian royalty hiring Minoan artists to paint frescos and shipwrights to build ships for Pharaoh Tuthmosis III.

However, in the Bronze Age, trade in the Mediterranean was not just bilateral exchange. By 1500 BC there was a wide and complex trading network stretching across the eastern Mediterranean with trade routes connecting far inland. This is evidenced by the discovery of a Bronze Age merchant ship off the coast of Turkey in 1984; The Uluburun shipwreck, whihc dates to between 1330 and 1300 BC was loaded with 20 tons of trade goods.

The cargo has been painstakingly analysed with exciting results: copper from Cyprus, tin from the Taurus mountains in Turkey, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, jars of terebinth resin 71 from Isreal but packed in jars from Canaan, large Cypriot storage jars contained olive oil or pomegranates, ingots of coloured glass as a raw material, baltic amber, one Italic sword, Mesopotamian cylinder seals, cumin, coriander, sage, safflower, olives, almonds, grapes, figs, grain, jewellery and 70,000 beads.

Also in the cargo were commodities that almost certainly came from Africa including ebony logs, an elephant tusk, 14 hippopotamus teeth, ostrich shell vases and worked ivory.

The crew or passenger’s personal belongings were also found and included a high status Phoenician sword and a pair of Mycenaean sealstones and axes suggesting an elite Phoenician and two Mycenaeans were on board. She possibly sailed from Abu Hasan, modern day Haifa in Israel and was possibly heading for mainland Greece, Crete or Cyprus.

The wide range of sources for her cargo is evidence of a complex trading network and a probably a merchant’s warehouse or active trading market at Abu Hasan where the cargo was collected over an extended period of time before being loaded.

Of Mice & Phoenicians

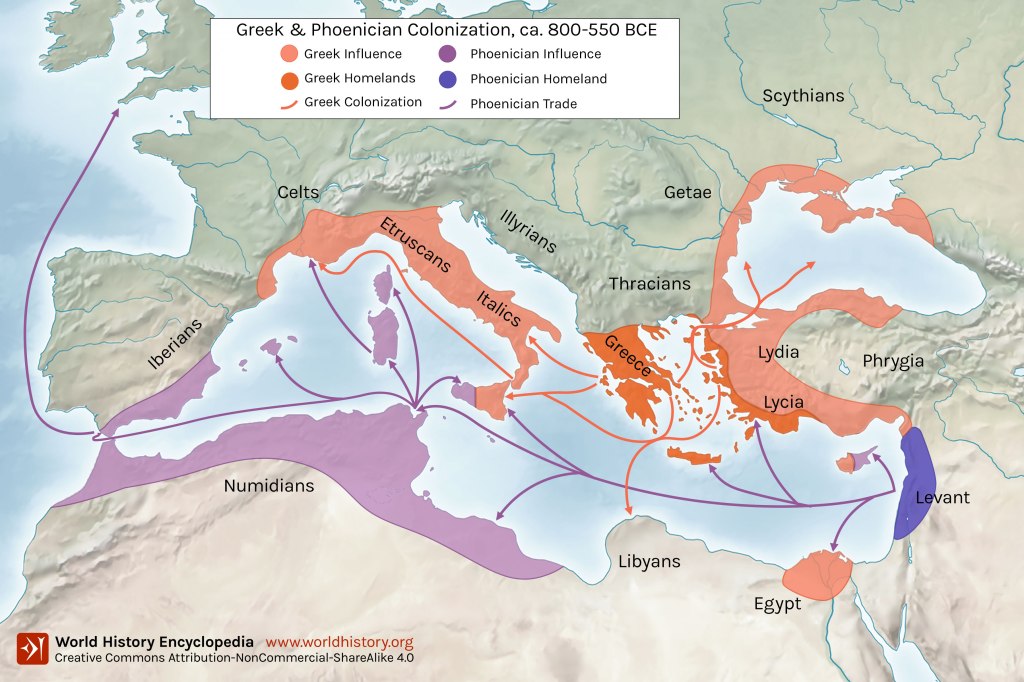

From around 900 BC the technology of ships and the skills of blue water sailors had developed to the point where the Canaanites, who the Greeks called Phoenicians, were no longer hugging the shoreline but routinely crossing the open Mediterranean.

Incredibly the humble house mouse, which is the second most widespread mammal on earth, is the marker used to measure the timescales involved with the expansion of trade.

Mice happily co-exist with humans, we unintentionally provide them with food, shelter and transport them to new and exciting places to colonise. The house mouse originated in India and by 12,000 BC had followed humans as far as the eastern seaboard of the Mediterranean. Over the next 10,000 years it spread into southern Anatolia and Northeastern Africa suggesting that people were moving along those routes but not with any great intensity. Then, around 1,000 BC, it appears in Greece and then rapidly colonises the whole central and western mediterranean coast folllowing the Greek and Phoenician traders and settlers. 73

The Greeks mostly stayed on the northern shores and east into the Black Sea while the Phoenicians settled the northwest coast of Africa and the southeast of Spain. The Greek expansion was partly driven by a lack of prime agricultural land on the Greek mainland but the Phoenicians were commercially driven. They were the ancient world’s most efficient and ambitious merchants buying and selling as far north as Celtic Britain where they sourced high grade tin and trading for lapis lazuli in Afghanistan.

11th to 6th centuries BC 75

By establishing trading posts on the coast of Africa and continuing to develop their 2,000 year old history of trade with Egypt the Phoenicians connected Africa with the known Western and Middle Eastern world. Gold and ivory from Ophir 76; glass, papyrus and linen from Egypt, gold and slaves from Nubia; along with ivory, copper, marble, timber, dyes, grain and olive oil from North Africa.

They also acquired tradable quantities of gold, slaves, silver, monkeys, precious stones, hides, hippopotamus teeth, ivory and elephants tusks from elsewhere in Africa showing that their trading posts along the North African coast from eastern Libya to southwest Morocco were reliably connected to Africa both north and south of the Sahara.

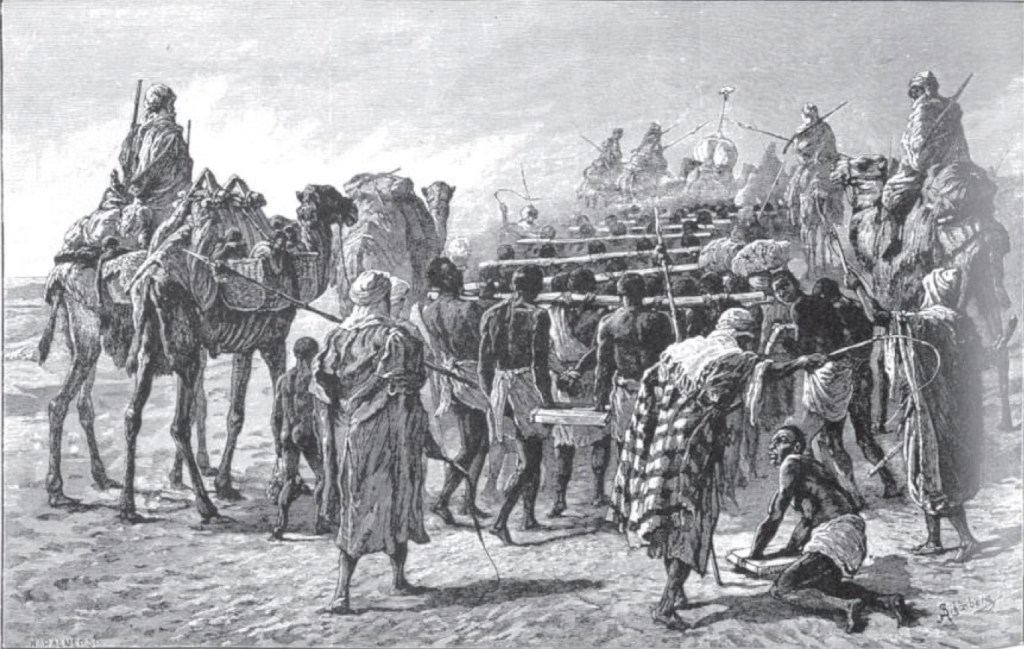

Across the Sahara

Herodotus, the Greek historian, writing between 430 and 425 BC describes in great detail, a caravan route across the Sahara from the Nile Delta along the northern edge of the Libyan desert. The route passed through Djerma in the hinterland of Tripoli which was the capital of the Garamantes, Lybian Berbers, who flourished as middlemen importing gold, ivory and slaves from the south to sell to a succession of Mediterranean civilisations. Their merchants either met the Garamantes at the trading hubs on the north coast or followed the caravan routes to Djerma or Ghadamis. 78 79

Herodotus’ route was just one of many caravan trails across the Sahara, with some dating to as early as 5000 BC. The crossing was difficult and dangerous requiring the expertise of seasoned and highly paid Berber guides and specially bred camels. From the 8th century AD Moroccans were cross breeding the dromedary camel and the Asian two humped Bactrian camel to create sleek speedsters that were useful to carry messengers and heavy weight beasts that could carry great loads:

“The value of the camel is not only confined to its high adaptation to severe desert conditions and its regulation of heat and water via its sweat glands: its ability for long-distance travel of about 48 km per day and its high carrying capacity (240 kg) make it a “ship of the desert,” in comparison with the load capacity of horses, donkeys, and mules at roughly 60 kg.” 80

Caravans could be huge sometimes comprising 10,000 camels that set off on the two month journey to cross a minimum of 1,000 kilometres of desert. They were guarded and led by Berbers who knew the routes and most importantly the water sources but to become separated from the caravan and guides meant a slow death by thirst and heat exhaustion. It was not unknown for whole caravans to disappear in the seemingly endless sea of sand, lost in a sand storm or misled by the ever shifting dunes that could bury the trails.

Coming south the caravans carried gold beads from Egypt and Syria, glass beads from North Africa and the Middle East, terracotta figurines and ceramics from Spain and porcelain from China. They also carried salt hacked out from mines in the desert by slaves who Ibn Battuta described as “black” and whose life at the mines was both horrific and short. For the traders a 90 kilogram block of salt was worth 450 grams of gold in Mali. 81

These routes only began to decline in the 16th century in the west after the Portuguese opened sea routes between Europe and West Africa. Until then they were a vital link between Europe, the Middle East and Asai bringing the commercial benefits of trade and the exchange of ideas with people living south of the Sahara but they are also part of the dark history of slavery.

Tidiane N’Diaye, a Senegalese anthropologist believes that between 15 and 17 million Africans were enslaved and transported across the caravan routes or shipped from the east coast of Africa to Egypt, Arabia, the Middle East and Turkey. N’Diaye argues the trans-Saharan and east African slave trade had a devastating impact on Africa because much of the trade involved the castration of men and boys; he believes this barbaric practice killed 70% to 80% of the slaves castrated.

Slaves crossing a minimum of a 1,000 kilometres of the Sahara desert would do so on foot usually carrying a 15 kilogram load. They were fed just enough to keep them alive and would be left to die in the desert if they became unable to keep up with the caravan, women and children were regularly systematically raped. It is estimated that around 20% of slaves died during the journey. 82

Those who survived were deprived of descendants and disappeared from history after they left Africa. 83

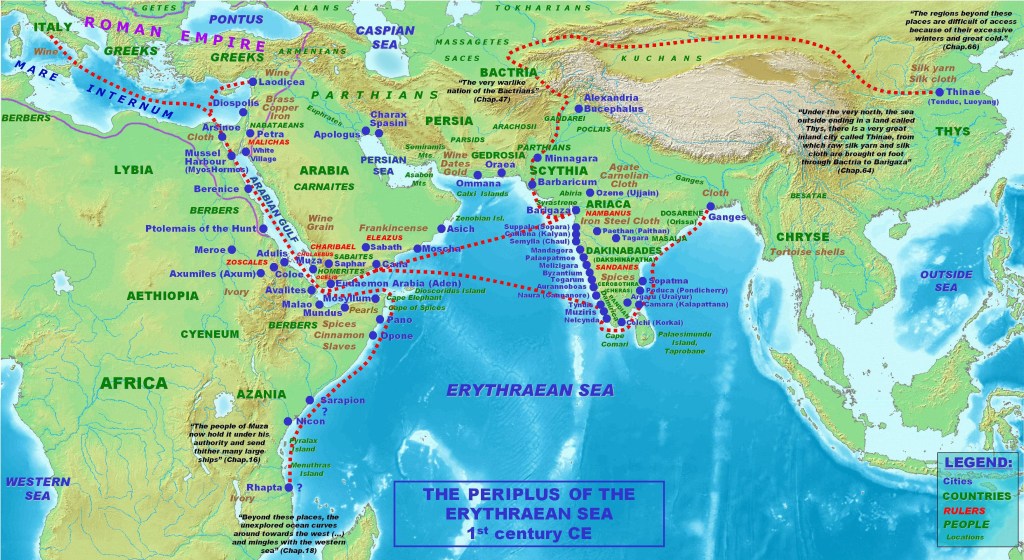

The Indian Ocean

Sometime between 30 and 40 AD, when Caligula was emperor of Rome, an unknown Egyptian, Greek or Roman merchant wrote a trader’s guide, a “periplus“, to the Indian Ocean. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea covers a huge area, from the Red Sea, east to the Persian Gulf, onwards to the Indian sub-continent and as far east as modern day Bangladesh.

In the other direction it leads traders round the Horn of Africa and south past the east coast of Africa. It notes landmarks as an aid to navigation and describes anchorages and ports along the way with the trading opportunities that could be found there.

The Periplus records ports from the Red Sea coast of Egypt through modern day Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya and finally to Tanzania; the products that can be traded by the 1st century Mediterranean merchant range from spices, fragrant gums, textiles and copper to slaves, ivory and tortoise shells. A complete table of ports and commodities can be found at Appendix A.

At the furthest point south on the east African coast it describes Menouthias and Rhapta which are believed to be the earliest documented mentions of Pemba, the island just North of Zanzibar, and Dar es Salaam or an ancient port nearby. The Periplus says the merchant can acquire “great quantities of ivory and tortoise shell” as well as metalwork such as spears, knives and awls with the “very big bodied men who live here”.

Most interestingly it says:

“The region is under the rule of the governor of Mapharitis 84, since by some ancient right it is subject to the kingdom of Arabia as first constituted. The merchants of Muza hold it through a grant from the king and collect taxes from it. They send out to it merchant craft that they staff mostly with Arab skippers and agents who, through continual intercourse and intermarriage, are familiar with the area and its language.” 85

This suggest that two thousand years ago, the coast of Tanzania was not only attracting traders from the civilisations of the Mediterranean but Arab merchants had already settled and intermarried there and through them Bantu-speaking people and southern African pastoralists were trading with Arabia and across the Indian Ocean. The Periplus provides the first evidence of Bantu and Arab intermarriage, leading to the creation of the Swahili people and their language.

We cannot tell whether in the 1st century proto-Swahili people were only at Rhapta or whether they were already emerging along the east African Coast from Tanzania in the South to Kenya and Somalia in the north. However by the 8th century Swahili culture and KiSwahili, the language, was a commonly held identity for people living in the towns of what would become known as the Swahili coast.

The Periplus does not record the advent of Indian Ocean trade, it documents routes and ports that must have been well know long before the 1st century AD. For example, Berenice and Myos Hormos, now Quseir-al-Qadim, were two Egyptian ports on the Red Sea founded in the 3rd and 1st century BC respectively. Archaeological finds at these two ancient ports show that Indian trade was passing through here probably on its way to Alexandria and onwards to Rome. 86 The commodities being imported are interesting as they can be divided into three groups:

- Luxury items from India – black pepper, teak, sandalwood, cotton, agate, amethysts, sapphire, pearls and ceramics;

- Non-luxury food items probably destined for an Indian community living in Egypt – mung beans, coconut, rice;

- And one luxury item that probably came from east Africa rather than India – Ivory

Italian wine and glassware was heading in the other direction.

When Finders Petrie excavated Memphis in 1908 he found significant evidence that an Indian community had been established there:

“In view of these connections there seems no difficulty in accepting the Indian colony in Memphis as being due to the Persian intercourse from 525 to 405 B.C. And the introduction of asceticism, already in a communal form by 340 B.C., points also to the growth of Indian ideas.” 87

We can only guess whether this community only comprised artists and craftsmen or whether it included merchant middle-men who facilitated trade between the Mediterranean world, India and East Africa.

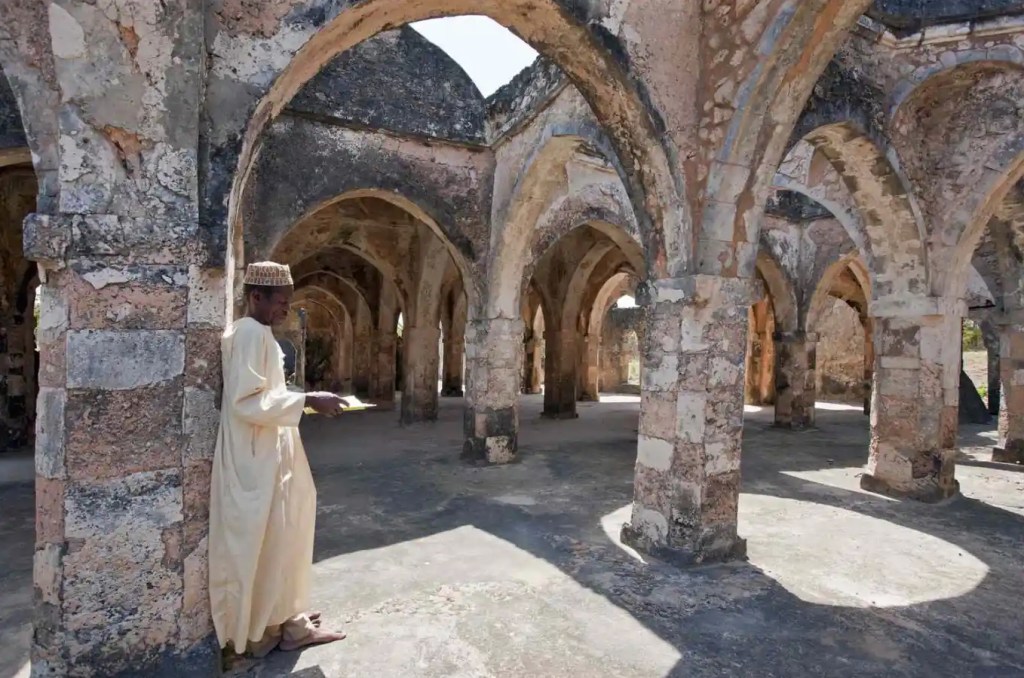

India and China had probably traded directly with the east African coast long before Persians settled there in the 6th century and Omani Arabs started to arrive in 684. The Omanis took Islam to the coast in 685 along with Islamic styles of architecture as evidenced by the first mosque being constructed in 830 on Lamu Island.

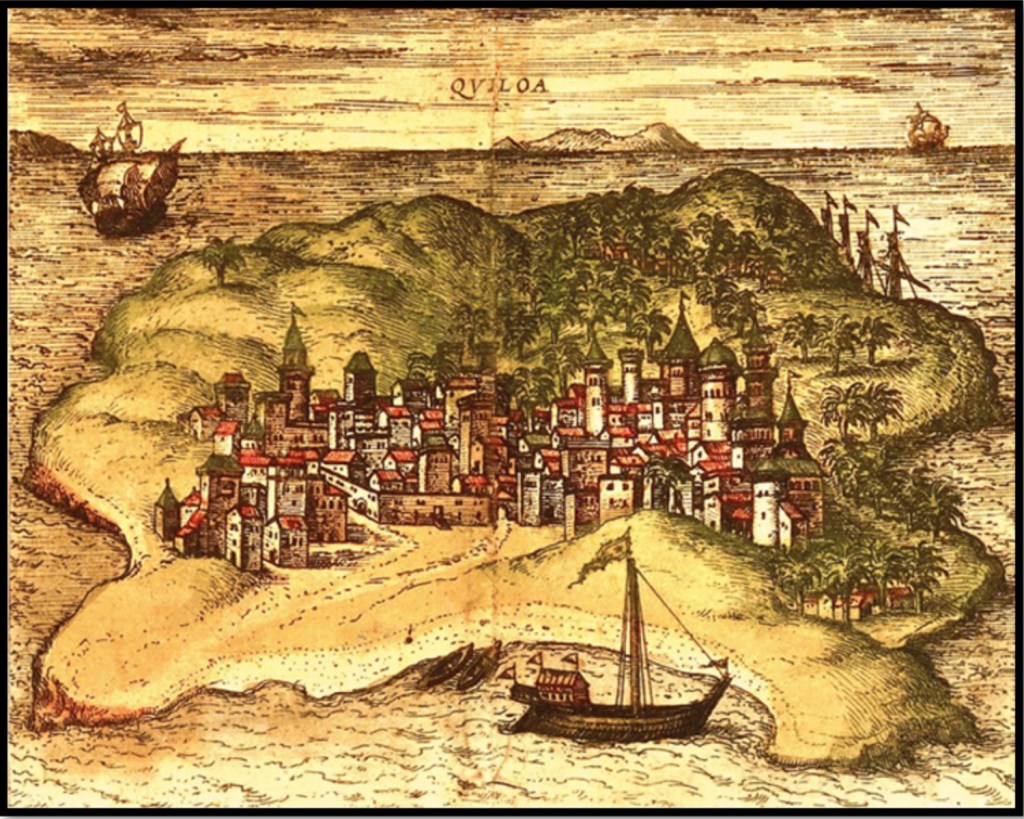

Kilwa was founded in 987 by Shirazi Persians who eventually ruled the coast from Mombasa and Malinda to Kilwa. At this time the Arab sailors rarely if ever sailed beyond Cape Delgado and referred to the Mozambique coast as El Mefaza meaning a place that was dangerous to life.

Sofala had become a trading port as early as 700 and became important as the entry port for the gold and Ivory trade with the Shona people in what is now Zimbabwe. It is likely to have originally been a Shona village trading directly with Indian merchants.

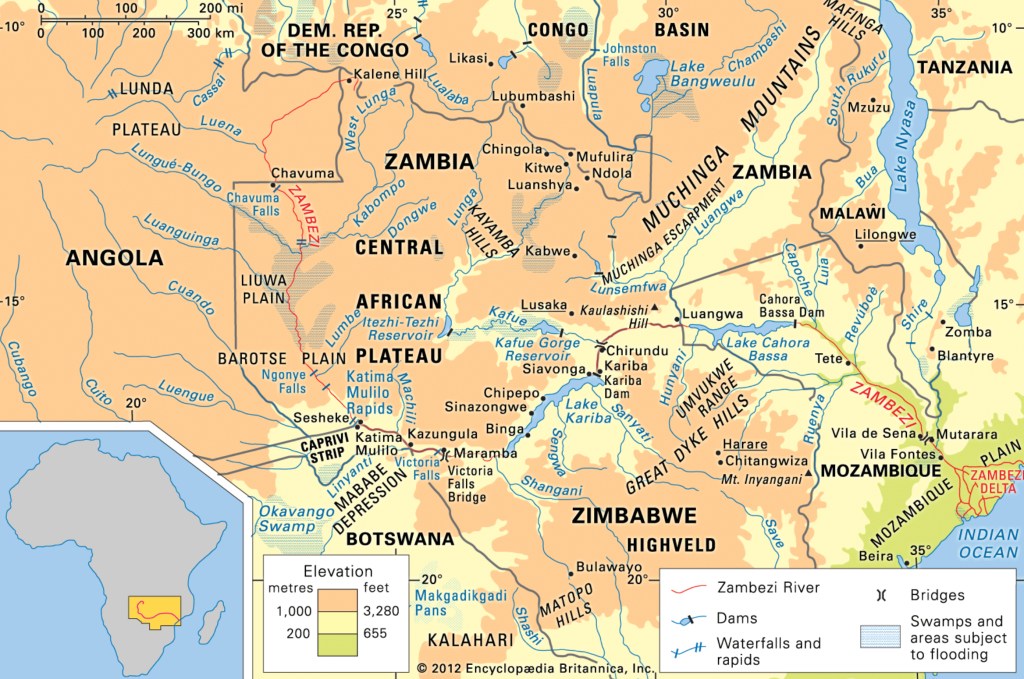

In 1147 an Arab Dhow was blown off course, rounded Cape Delgado and was swept south and, as a result, discovered Sofala. It was quickly adopted as a colony of Kilwa whose merchants took control of the gold and ivory trade with the interior. At some point after this they also discovered the mouth of the Zambezi and navigated 500 kms inland to the Kebrabasa falls, which are now submerged under Lake Cahora Bassa beyond Tete, and established the town of Sena as another gold and ivory trading centre.

The trade networks worked their way inland and by the 8th century settlements in the Limpopo valley were trading with the coast. One example of many is at Schroda where archaeologists have excavated an Iron Age settlement overlooking the Limpopo River where South African, Zimbabwe and Botswana now meet and about 60 kms west of the town of Beitbridge. It was occupied from around AD 900 and is one of a number of settlements of a similar age in the area where Mapungubwe developed as an important Shona city and trading centre in the 11th century.

Glass beads have been found at Schroda provide the earliest known evidence of long distance trade with the coasting southeastern Africa. The is evidence that the people living here were trading ivory and animal skins in exchange for beads and cloth, trade which Archaeologists believe enabled Schroda to become the political and economic centre of the Limpopo Valley. 89

Nearby at Letaba, in the Kruger National Park, excavations have found imported ceramics from the Persian Gulf and glass beads from Asia also dating to the 10th century. The types of pottery discovered at Letaba have also been found at Kilwa, Shanga, and Chibuene confirming that an early trade route existed between settlements on the Limpopo River and the coast that predates the rise of the Shona Kingdom, Mapungubwe, and Great Zimbabwe. 90

Around AD 1000 a nearby settlement at Leopard’s Kpoje, often referred to as K2 developed . The people living here were herders and hunted wild animals but also developed large scale industry making disc beads from ostrich eggshell, giant land snail shells and freshwater mussel shells as well as making ivory bangles. They were exporting ivory tusks but probably keeping the worked objects in the valley where there is evidence of local trading. And, in return, they were importing marine shells and beads that originated in the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia and India. 92

Al-Mas’udi visited east Africa in around 916 recording that Rhino horn was being worked into belts with gold and silver and traded to China:

The kings and the important ones of China like these jewelry above all, they even pay as much as 2000 or 3000 dinars 93 for it. Gold is used in it and the total is of such splendor and also strong, sometimes different kinds of precious stones are put in it, fixed in it with gold nails. 94

He wrote that there were gold mines in the interior and huge elephants which the locals hunted for their tusks that were shipped to Oman before being sold on to India and China. In china they were used to make ivory “carry-chairs” which he says officials and people of high rank had to use when they visited the “king”. In India ivory was made into bangles, knife handles and the hilts of ceremonial swords but most of it was used to make chessmen and gaming pieces.

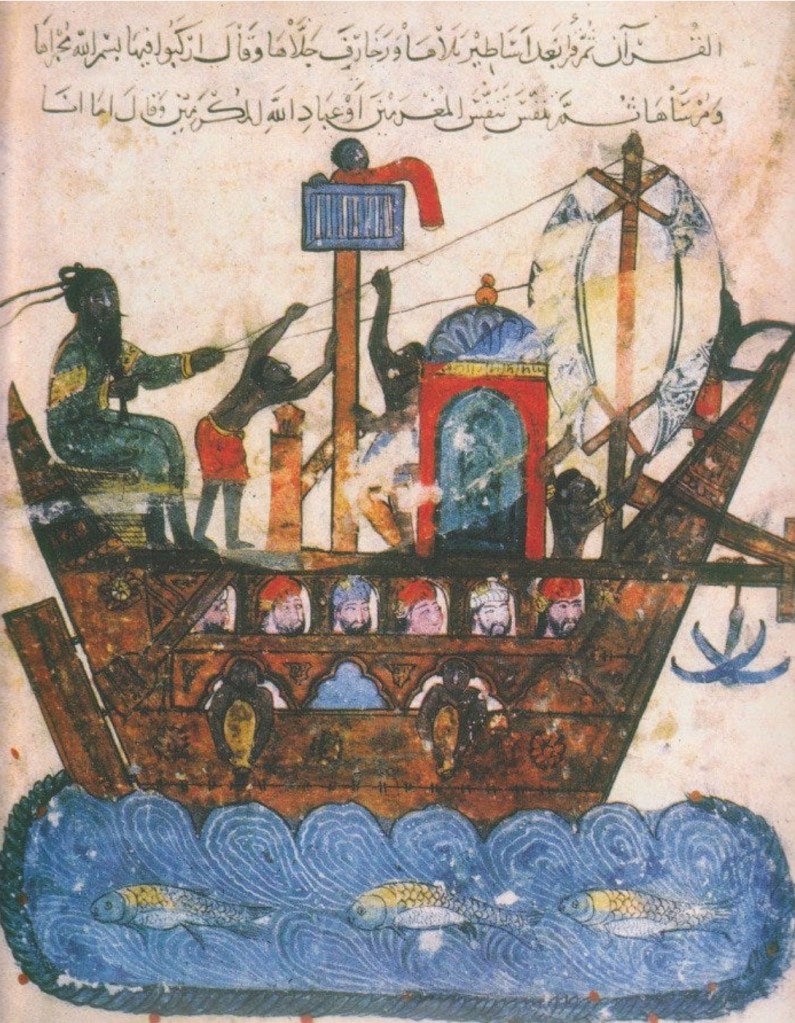

By the time Ibn Batuta visited the coast in 1332 most of the settlements were Muslim and Arabic was the commercial language of the whole Indian Ocean trading network. 96

Nature created this great maritime highway; in October and November cold air is drawn from the Himalayas and blows across the Arabian Sea accompanied by the monsoon current traveling anti-clockwise around the southern coast of Arabia and south down the east coast of Africa. Wind and current carried merchants from India and Sri Lanka to Arabia and from Arabia to the Swahili coast: Malinda, Mombassa, Zanzibar and Kilwa, then further south to Mozambique Island and Sofala.

From June to September the wind and current reverse as the Indian sub-continent heats up and air is sucked towards southern Asia. The southeast monsoon, which carries rains to India and beyond, also carried merchants north from the Swahili coast back to Arabia, western India and on into the Bay of Bengal.

African exports included:

| Gold | Ivory | Slaves | Iron |

| Copper | Hippo Teeth | Rhino Horn | Tortoiseshell |

| Mangrove Poles | Ebony | Sandalwood | Pearls & Seed Pearls |

| Rock Crystal | Salt | Grain | Rice |

| Ambergris | Animal Skins | Incense | Spices |

And in exchange, from the 1st to the 17th centuries, Africa imported huge quantities of beads: red glass, agate and carnelian from Cambay, Khambhat, in the Indian state of Gujarat; plus red glass beads coloured with copper from China 97 and Sri Lanka.

Imported glass beads dating to between 600 and 900 have been recovered from sites across southern Africa including Chibuene in southern Mozambique, Makuru in Zimbabwe, Schroda in the Limpopo valley and in northeastern Botswana. They were an important trading “currency”. Trade Wind Beads or Trade Beads, are vital evidence of the extent of trade across the region. They are found across all of Africa dating to pre and post colonial times and sometimes in vast quantities such as over 100,000 at Mapungubwe or 26,000 at Great Zimbabwe.

As well as beads, cotton cloth and copper ingots were commonly used as currency and the earliest European visitors often quote prices for slaves and ivory in terms of lengths of cloth. Africans valued the internationally sourced products that found their way inland along the trade routes including: ceramics, jade, jewellery, silk, spices, salt and glassware.

Ibn Battuta was a Berber traveller, explorer and writer who lived from 1304 to 1369.

He travelled extensively across Asia, Africa and Europe. After 29 years of journeys he dictated his memories to Ibn Juzayy who wrote The Travels that was published in three volumes long after his time. 99

Ibn Battuta visited parts of the African east coast including Mogadishu where he arrived along with several merchants.

He reported that when the ship anchored young men came out to meet it in small boats; on climbing aboard they gave a plate of food to a merchant who would then disembark and accompany the young man to his master’s house. The merchant would stay here while his host bought and sold for him.

Ibn Battuta described the town, which he called Maqdashaw, as being enormous, inhabited by rich merchants who owned many camels and sheep. Wood was manufactured here and exported to Egypt and he was given a tunic made from Egyptian linen with an Israeli trim.

After Mogadishu he sailed south to Mombassa which he describes as being very poor without any obvious trade. Further south he reached the “large city” of Kilwa which he called:

“Kulwa in the land of the Zinj people ……. one of the finest and most substantially built towns“.

He remembered that many of the inhabitants were black “Zinj” people with tribal tattoos on their faces. The sultan, Abu’l-Muzaffar Hasan, gave slaves and ivory as gifts to supplicants and:

“…. used to engage frequently in expeditions to the land of the Zinj people, raiding them and taking booty”

Whilst at Kilwa he heard of the town of Sofala that lay two weeks sail to the south where he was told that gold arrives from the interior in great quantities. By the 15th century there were 35 independent trading cities on the Swahili Coast each with a hinterland of inland trading routes.

The Portuguese arrived on the east coast in 1498. Vasco da Gama anchored off Quelimane and met Africans and persons of a lighter colour who spoke a little Arabic. He carried onto Mozambique Island where he met many Arabs who told him about trade on the coast. When the Arabs discovered that the Portuguese were Christians their relationship quickly deteriorated and ended with a skirmish followed by the Portuguese destroying a village where they had been attacked whilst collecting water. 101

This inauspicious start was a portent of the future and according to Mark Cartwright:

“From 1502 the Portuguese were intent on muscling in on the region’s trade, and they set about sinking ships, destroying cities, and building forts to achieve that goal.”

….. The Portuguese had superior weapons, and they used them to cause havoc amongst the Swahili city-states whose rivalries (for example, between the sultans of Malindi and Mombasa) prevented them from forming a unified response to this new and deadly threat. 102

Early Trade in Malawi

The topography of this region dictated trade routes and its development. 104

The inhabitants of Malawi were industrious and taken as a whole Malawi was comparatively rich in natural resources; there was abundant iron ore, salt from steams and Lake Chilwa and plenty of land with access to water for agriculture. Cotton was grown and woven into cloth in the Shire Valley and bark cloth, made from the inner bark of the njombo tree, was made by specialists who searched the bush for suitable trees. 105

The lake was, and still is, full of fish providing a rich source of protein that could be dried on the lake shore. Middlemen worked along the shores of the lake buying fish which they carried further inland to sell. The fact that iron ore was common in the highlands whilst salt, fish and agriculture were prevalent in separate parts of the lowlands strongly suggests that trade between Malawian people had always been essential and common.

Geography naturally connected Malawi to the coast via the Shire and Zambezi Valleys so Malawians were trading with Arab merchants from as early as the 10th century when they became established on the Zambezi. Traders came up from the coast exchanging salt, cloth and beads for tobacco, beeswax and wild rubber. 106

The area immediately south of the lake where Mangochi would eventually develop was the natural point for traders to pass round the lake and there are suggestions that local chiefs were charging a tax of cloth or beads to pass through the area.

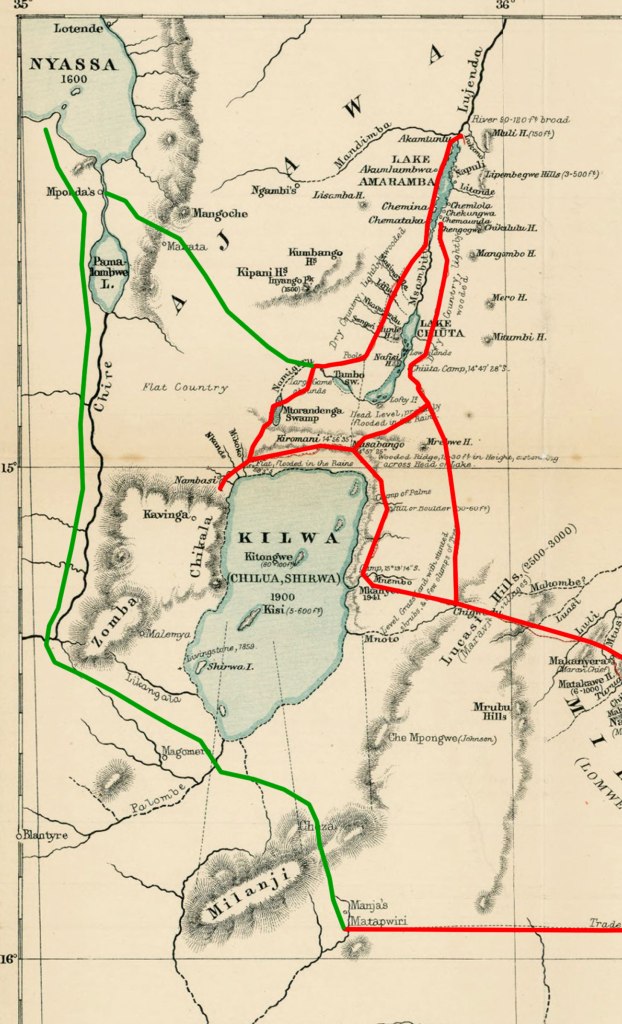

Very little archeological work has been carried out in Malawi but we do know that the Maravi state had a major centre or capital at Mankhamba, near Salima to the west of the lake. When the site was excavated in the 1980s and 90s the archeologist, Yusuf Juwayeyi, found imported Indian glass beads, 31 shards of Ming porcelain, large quantities of worked ivory and copper that had to have come from at least 570 km away. 107 Juwayeyi places the foundation of Mankhamba in mid-1400s and the finds suggest that the Chewa people living here were involved in long-distance trade probably exchanging ivory bangles and iron tools for cloth, beads and Chinese porcelain.

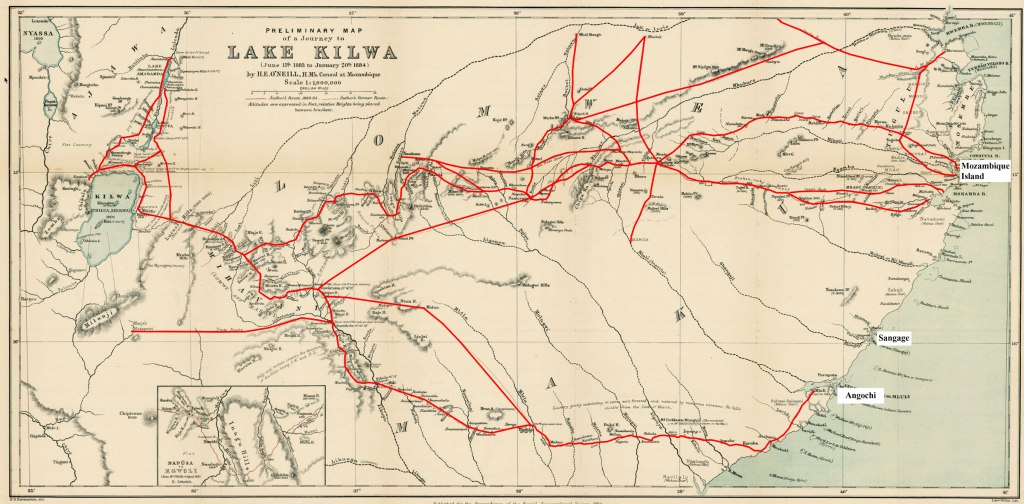

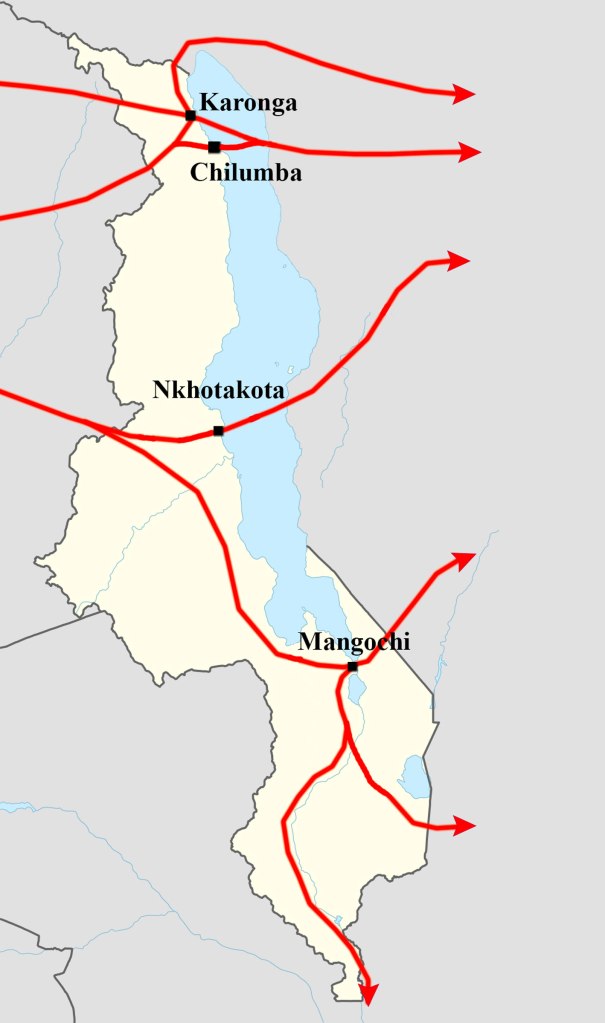

When H.E. O’Neill travelled from the coast to Lake Chilwa in 1883 he not only marked his own route but showed where he saw or heard of trade routes. The map above shows the combination of those routes in red and, although it dates to the 19th century it is likely that these were long established routes.

The map shows in green how the coastal routes were probably connected to Mankhamba and to the southern end of the Lake.

For 400 odd years different groups of people moved into Malawi coming from the Congo basin, Mozambique, the Zambezi and Luangawa valleys and from as far south as KwaZulu Natal. There were elephant hunters, traders, farmers, iron workers and warriors. A more complete story of these arrivals can be found at The Demise of Malawi’s Elephants Part 1.

At the end of the 18th century Malawi had escaped the worst of the ivory and slave with the land west of the lake still reported as being elephant rich and whilst there was a well established trade in ivory to the north and south of the lake it was comparatively small scale.

Sadly Malawi went through a series of changes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that dragged it into the line of fire of the elephant hunters and the slave traders. The story of those years can be found at The Demise of Malawi’s Elephants Part 2.

By the 1840s Malawi had gone from being a backwater with the ivory and slave trades flowing around it to becoming a hub for both trades with traders like Salim-bin Abdullah (Jumbe) shipping 20,000 slaves a year across the lake from his base at Nkhotakota, Mlozi trading slaves and ivory from this base at Karonga in the north and the Yao ravaging the villages in the south.

Malawi was being systematically harvested for slaves and ivory.

For a more complete picture of how the slave trade developed inland from the Swahili Coast see The East African Maritime Slave Trade.

Conclusion

For a few months in 1860 Europeans thought a young German, Albrecht Roscher, who had reached the eastern shore on 19th November 1859, was the first white man to see Lake Malawi.

Roscher was murdered in March 1860 soon after he left the lake on his way back to Zanzibar so his remarkable journey has mostly been forgotten.

The news of Roscher’s so called “discovery” reached Europe via Zanzibar before the world heard that another explorer, David Livingstone, had walked up the Shire Valley from the Zambezi River reaching the southern end of the lake on 17th September 1859 beating Roscher by two months.

In truth he lagged behind Gaspar Bocarro, a Portuguese explorer who had seen the lake 250 years earlier on his way from Tete to Kilwa.

However, Livingstone, an accomplished self publicist, never let facts get in the way of a good story and loudly proclaimed that he had discovered the lake which the Chewa people living nearby told him was called Nyasa, the Chichewa word for a lake.

Bocarro, Roscher, Livingstone and the press of the Western World all ignored the reality that different groups of African people had been living by the lake for at least 70,000 years and, more recently, hundreds of Arab traders had seen it as they trudged along ancient trade routes from the coast to the interior.

The 19th century Europeans reading their newspapers and the many books published by the Victorian explorers imagined Burton, Livingstone, Stanley, Speke, Grant, Thomson et al. alone or with the odd trusted European companion, compass in hand, hacking their way inland through dense jungle, wading crocodile infested rivers to arrive in native villages where they were welcomed as the first non-black person they had seen.

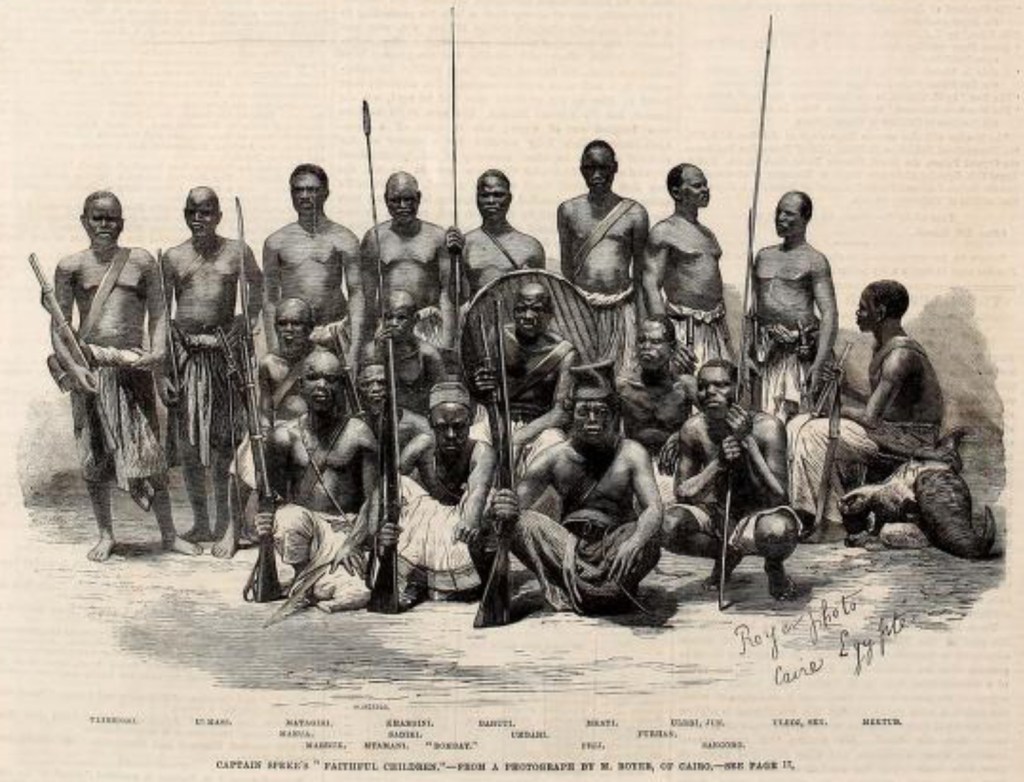

Sidi Mubarak “Bombay” is seated in a chair at the centre of the photo 109

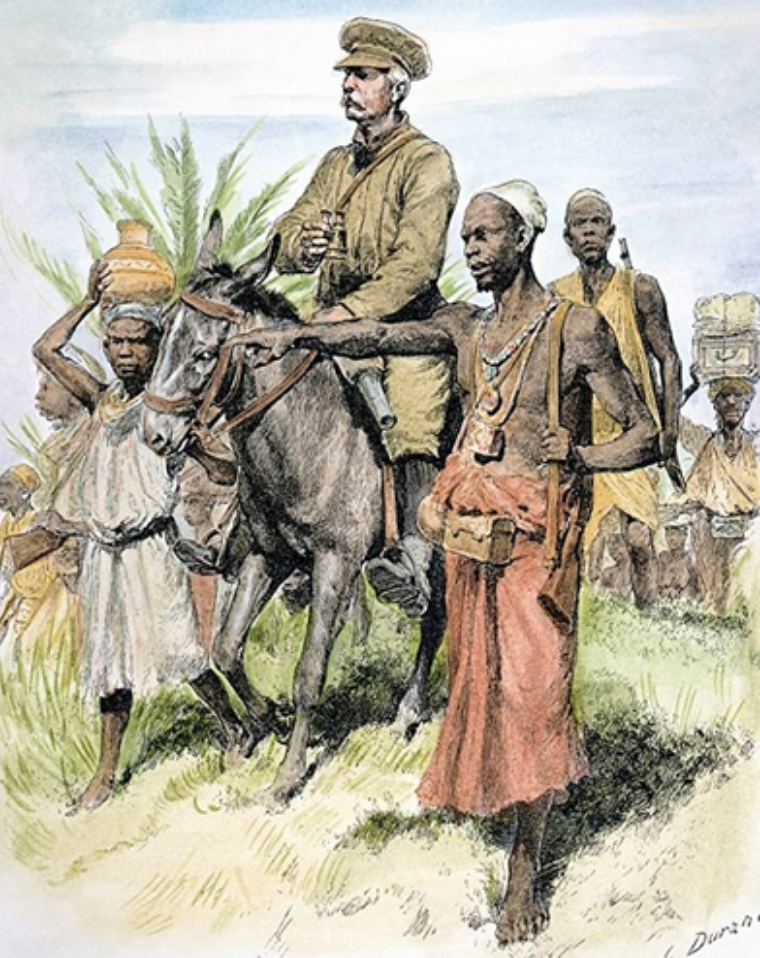

Whilst accepting that it took real courage to head into the interior of Africa in the 19th century it should be better understood that the explorers were mostly traveling along well established trade routes and often assisted by Arab or Swahili slave traders.

They were accompanied by African interpreters, guards and porters often in such large numbers their caravans must have seemed like private armies on the move: Stanley took 3 Englishmen and 230 Africans from Zanzibar to help him explore the great lake region in 1874. They often employed African caravan leaders and established military-style command structures and some of these Africans men travelled further and more frequently on expeditions that any European

Men such as James Chuma (right) whom Livingstone freed as a child slave in Malawi in 1861 or the other Nasik Boys and the Bombay Africans, freed slaves educated or just abandoned in India but who returned to Africa as guides and missionaries including the loyal servants of Livingstone who carried his body back to Zanzibar in 1875.

These Africans facilitated their employers’ great explorations, acting as go-betweens with indigenous chiefs, buying food during their journeys, tending for their masters when inevitably they became ill and carrying them when they were too weak to walk.

The explorers mention a few by name but the vast majority are nameless. Donald Simpson who wrote the Dark Companions, a marvellous study of these men sums up some of most well known:

“Bombay (Sidi Mubarak “Bombay”) saw the great lakes of East Africa, went with Stanley to find Livingstone, and crossed the continent from east to west, in journeys that must have totalled more than 12,000 miles. His solid comrade Mabruki Speke accompanied him on his first two journeys, saw von der Decker murdered, assisted Stanley quell a mutiny, and helped bring Livingstone’s body to the coast, before dying on the shores of Lake Victoria. Susi, who crossed the Indian Ocean with Livingstone, carried the dying missionary through the swamps of Lake Bangweolo. He knew praise and rejection, and chose the site of an African capital, now Kinshasa, before ending his days as an honoured stalwart of the Universities Mission. 111

Livingstone had a significant effect on the future of Malawi; he returned to Britain and proclaimed that he had found an idyllic land that needed to be cleansed of the evils of the slave trade and the way to do that was through the three C’s: Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation.

Livingstone’s lecture tour on his return from Malawi and the Zambezi sparked the interest of missionary societies and led to the first mission to Malawi arriving in 1861.

Livingstone’s impact on the slave trade in Malawi was simply that he brought the East Coast trade to the attention of the British public; this initiated a chain of events that began with the Magomero Mission that, in turn, led to other missions and a commercial company set up to supply them who quickly got entangled with the slavers. This motivated various adventurers and self-appointed representatives of the British Government to rush in to save the day. Unofficial became official, the slavers were stopped and British colonists began to arrive to grow, not cotton, but tobacco, coffee and tea.

How a bizarre mix of merchants, elephant hunters, mad sportsmen, adventurers, soldiers, social misfits, colonists and their African companions eventually stopped the slave trade will be the story of my next post.

Footnotes

- The British members of the Magomero mission party were Bishop Charles Mackenzie, his deacon Henry Rowley, another priest in Lovell Proctor, the lay superintendent Horace Waller, and Reverand H.C. Scudamore who had no defined role. Four black Christians had been recruited in Cape Town, they were ex-slaves who had been freed by the East African Squadron: Charles Thomas and William Ruby who were originally from northern Mozambique ; Henry Job from Sena and Apollos le Paul from Tete. the last member of the group was Lorenzo Johnson from Jamaica who had been a slave in the USA. ↩︎

- The phrase “The Warm Heart of Africa” was first coined by Frank Johnston (1942 – 2020) a British tourism officer working for the Malawi Department of Tourism. ↩︎

- John McCracken (2012) A History of Malawi 1859-1966. Woodbridge, Suffolk: John Currey ↩︎

- Ptolemy, a Roman geography produced a map in the 1st century AD that showed the Mountains of the Moon as the source of the Nile. His knowledge of this mythical mountain range seems to have been based on “I knew a bloke who met a bloke who said he knew someone……” Remarkably 1,800 years later people were still taking this rumour seriously and several Europeans chased around north east Africa searching for the Mountains of the Moon as the source of the Nile. ↩︎

- Res nullius is a term of Roman law meaning “things belonging to no one”; that is, property not yet the object of rights of any specific subject. A person can assume ownership of res nullius simply by taking possession of it. ↩︎

- Thomas Pakenham (1991) The Scramble for Africa. London: Abacus ↩︎

- Bradsaw-Foundation ↩︎

- Andrew Linklater (2016) The ‘Standard of Civilisation’ in World Politics Linklater-2016 ↩︎

- wiki-commons-1884 ↩︎

- Alexis Heraclides (2015) Humanitarian Intervention in the Long Nineteenth Century: Setting the Precedent Heraclides-2015 ↩︎

- The phrase “Scramble for Africa” was first coined by the British in 1884 ↩︎

- Pakenham (1991) ↩︎

- Louise Henderson (2015) Publishing Livingstone’s Missionary Travels Henderson-2015 ↩︎

- George Martelli (1970) Livingstone’s River. Trowbridge: Readers Union ↩︎

- David Livingstone (1857) Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: John Murray Livingstone-Missionary-1857 ↩︎

- Henderson (2015) ↩︎

- David Livingstone (1857) Dr Livingstone’s Cambridge Lectures. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. Livingstone-1857 ↩︎

- David Livingstone (1857) Lectures ↩︎

- Georg Smith arrived at the Cape to work with the Khoisan people, He settled in the Glen of the Baboons and established the first mission station. Polin-Institiute ↩︎

- Man the Master British-Museum-Slaves ↩︎

- Teju Cole (2012) The White-Savior Industrial Complex Cole-2012 ↩︎

- Hilaire Belloc (1898) – The Modern Traveller (1898) Belloc-1998 ↩︎

- “The white man’s grave” was first coined by F.H.Rankin in 1836 to describe the west coast of Africa, ↩︎

- Sebastian Munster’s map of Africa 1550 – see an interative version at Munster-map-1550 ↩︎

- The phrase “dark continent’” was popularised by Henry Morton Stanley. In 1878 he published his book “Through the Dark Continent”. ↩︎

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City ↩︎

- Christopher Ehret (2023) Ancient Africa: A global History to 300 CE.Princetown: Princetown University Press ↩︎

- Matthew McCarty (2023) The Libyans. Matthew-McCarty-2023 ↩︎

- Chukwukajustice (2017) Traditional Pottery in Nigeria Chukwukajustice-2017 ↩︎

- Ehret (2023) and Mnena Abuka (2020) Women in Gungun Share their Experiences in Pottery Making Mnena-Abuku-2020 ↩︎