- Introduction

- The Scale of Slavery in Ancient Rome

- Origins of Slavery

- Slaves as the Spoils of War

- Other Sources of Slaves

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

The Scale of Slavery in Ancient Rome

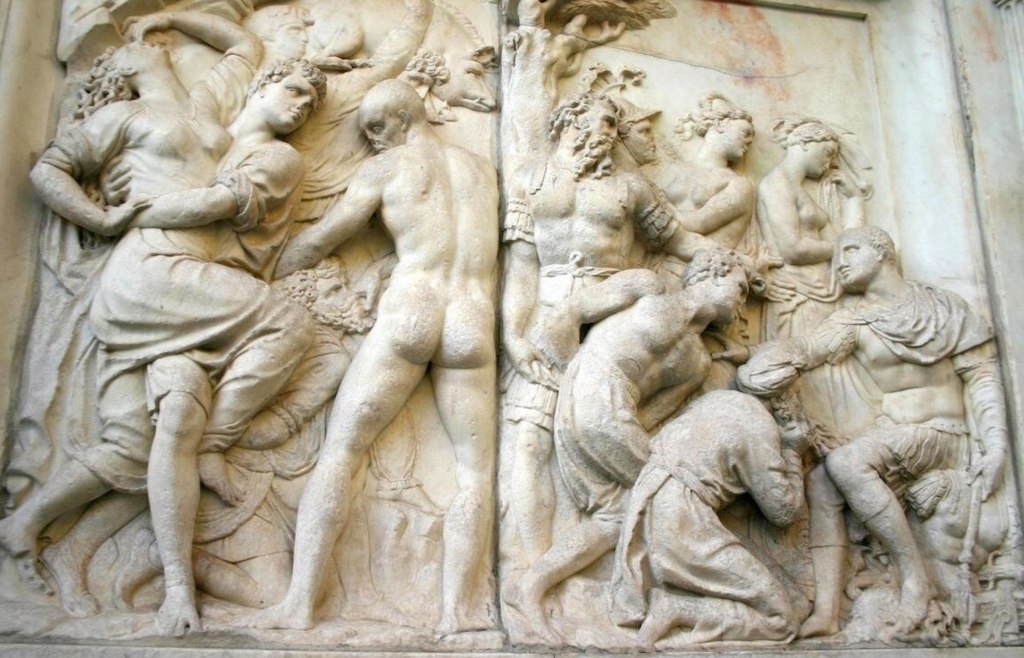

Monument to Giovanni delle Bande Nere, Florence, Tuscany, Italy

The scale of slavery in Rome and its Empire is staggering. In 50 BC there were between 1.5 to 2 million slaves in Italy 1 and by the end of that century between 2 to 3 million representing 33 to 40% of the total Italic population. 2 By AD 100 there were probably 400,000 slaves inside the city of Rome itself.

As Rome progressed through the Imperial Age the slave population in Italy may have decreased but it significantly increased in the Empire. Under Augustus the population of the Empire was around 60 million people which included in the region of 10 million slaves. That is more than the population of London, similar to the modern population of Greece and more than many other countries including Austria, Hungary or Israel. 3

In 200 BC very few houses in the city would have had more than one slave but by the late 1st century AD we know Pliny the Younger, a typical upper-class landowner owned 500; Lucius Pedanius Secundus, a senator owned 400 enslaved domestic staff and Pudentilla Apuleiu, a rich provincial lady, gave her sons 400 slaves as a gift.

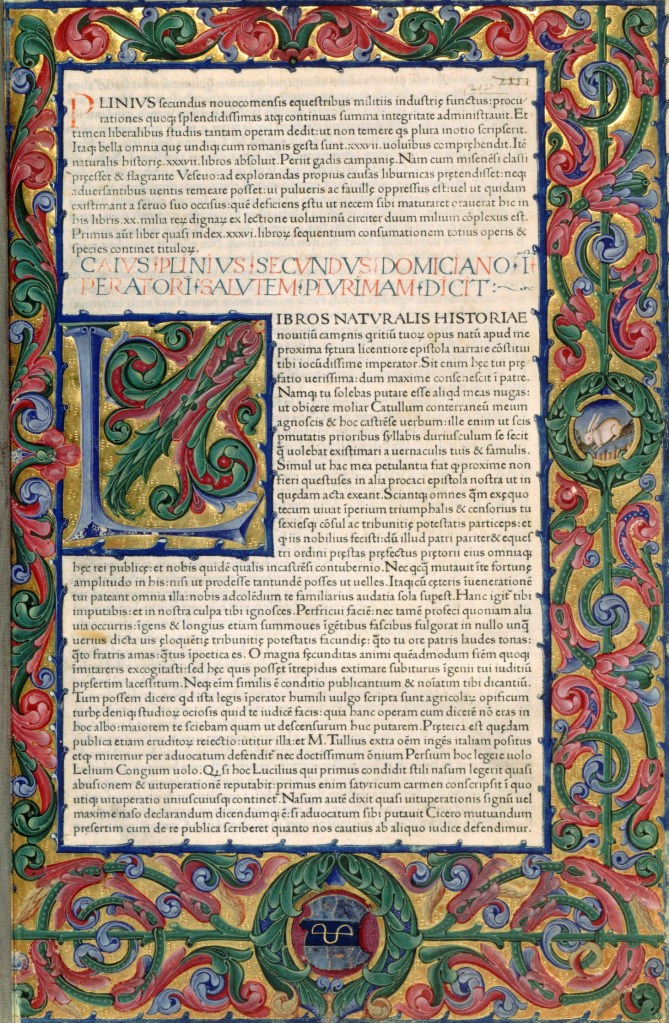

In Natural History Pliny the Elder tells the story of:

“Gaius Caecilius Isidorus, the freedman of Gaius Caecilius who in the consulship of Gaius Asinius Gallus and Gaius Marcius Censorinus {8 BC} executed a will dated January 27 in which he declared that in spite of heavy losses in the civil war he nevertheless left 4,116 slaves, 3,600 pairs of oxen, 257,000 head of other cattle, and 60 million sesterces in cash, and he gave instructions for 1,100,000 to be spent on his funeral.” 4

This short paragraph reveals not only that Isidorus owned a vast number of slaves and was fabulously rich but that he himself had been a slave. This provides an insight to the complex Roman world, the fact a slave could be freed is unusual enough in the ancient world and it is especially surprising that he could become so rich but equally remarkable is that an ex-slave had no qualms about owning people.

Trajan emperor from 98 to 117 AD probably owned in the region of 20,000 slaves although that would have included a large number of public servants such as tax collectors. 5

From 65 BC until 30 BC approximately 100,000 new slaves were needed each year in Italy alone; this rises to a need for 500,000 each year between 50 BC and AD 150. 6 We will see below that that this demand was fulfilled from a variety of sources.

Roman citizens were nearly always surrounded by slaves, they were ubiquitous, engaged in every type of work except holding public political office or serving as soldiers in the army although even that rule was flexible in times of crisis.: in 215 BC during the second Punic War large numbers of casualties led to a shortage of soldiers, to supplement a recruitment drive the state purchased either 8,000 slaves or 24,000 slaves who became known as the Volones. 8

Lenski puts forward the view that:

“…. the openness of the Romans to the enslavement of all peoples and races and their readiness to deploy slaves in nearly every economic sector allowed the Romans to develop what was arguably the most socially integrated slaving system in world history.” 9

The slave was isolated from society, at best an observer of the lives of the free but often trapped on a remote estate or mining complex, he or she had no rights, no voice and suffered whatever humiliation their owner saw fit to impart. Keith Bradley who has probably considered slavery from a slave’s perspective more than most historians argues:

“From a cultural point of view, therefore, slavery was at no time an incidental feature of Roman social organisation and at no time an inconsequential element of Roman mentality.” 10

Origins of Slavery

To approach the subject of Roman slavery across the whole history of Rome is well beyond the scope of this essay. But it might be helpful to set the scene by looking at the origin of Rome and the Romans and the first slaves in a culture that would develop to become totally dependent upon them.

It has often been suggested that the majority of slaves in the Roman Republic and in the Imperial Age were prisoners of war. but recent studies have suggested that this is not the case although there is no doubt that slaves of war played a significant part in the growth of slave ownership in Rome. It is interesting to look at some of the earliest records of slaves being taken in war and how the Roman state benefited financially from their sale in both the days of the Republic and in the first few hundred years of Imperial Age.

Slavery was arguably the engine that enabled the rapid expansion of Rome from a powerful city state to masters of an Empire of five million square kilometres stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Euphrates River and the Scottish borders to the Sahara Desert and many kilometres up the Nile towards modern day Sudan.

Where Shall we Start?

The first question that needs to be answered when looking at a single facet of Roman culture such as slavery is where to start and where to finish. The Roman Kingdoms were followed by the Republic and then the Empire, a period of over 1,200 years in the West, and nearly another 1,000 years again before the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire. It goes without saying that the Romans were never one society nor a single static culture.

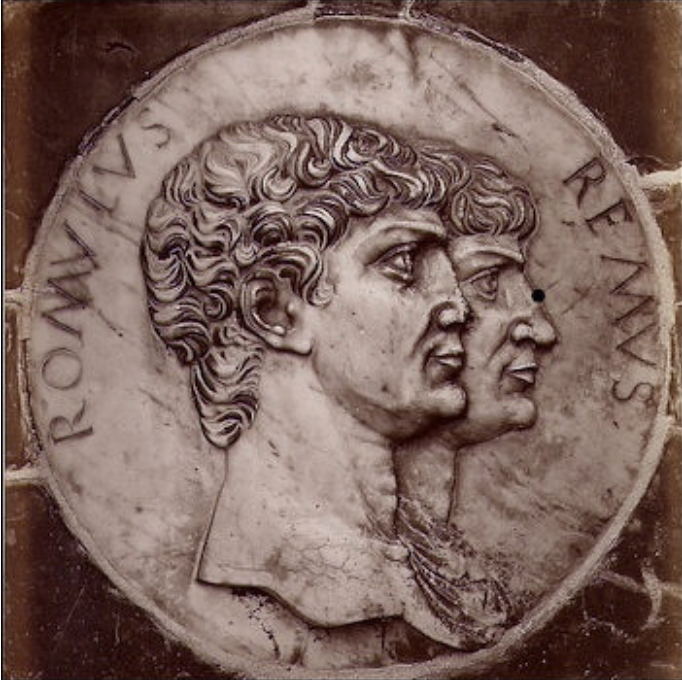

The Romans traditionally accepted that Rome was founded on the 21st April 753 BC; this wonderfully specific date is, of course, completely fictitious and bears little or no relationship to any of their foundation myths or to archaeology which tells us people had been living on the Palatine hill since at least 1,000 BC. However, let us not spoil a good story with dull facts.

So, on the banks of the River Tiber in Central Italy on a glorious spring day a fellow called Romulus, who by the way could boast of a few gods and a Trojan hero amongst his ancestors, built Rome’s first hut surrounded by a fence or a ditch on the Palatine Hill.

Romulus had been brought up in the area by a she-wolf 11 along with his twin brother Remus but he pretty quickly bumps off Remus once the city founding starts, Remus having had the temerity to pick a different hill and then jump over Romulus’ new defences in a disrespectful manner.

Civis Romanus Sum

So, Rome’s first citizen was a murderer, a fratricida no less, yet Civis, Romanus Sum, I am a Roman Citizen, was not just a proud boast but came to be a protective shield across a great swathe of the known world. The existence of an empire and the need for such protection was still a long way off but who were these first Romans?

After removing his twin from the picture and finishing his hut Romulus took stock of his new Kingdom and realised that he was very short of a population. It is no fun being a king if you have no subjects, so he put the word out that his city, or to be more precise the Capitoline Hill next door was now an asylum; 2,636 years later the United States had a similar idea and Emma Lazarus’ poem inscribed on on the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour expresses that same need for population:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’” 12

Livy, the Roman historian, writes that Romulus, went much further than calling for “huddled masses”, he wanted runaway slaves, convicted criminals, exiles, paupers, debtors, foreigners, refugees, outlaws and outcasts; anyone who had no place elsewhere in Italy.

The story is that Romulus’ motley crew of runaway slaves, convicted criminals, exiles, paupers, debtors, foreigners, refugees, outlaws and outcasts, etc. lacked wives so he invited the neighbours, the Sabines, to a religious festival. On Romulus’ signal each of his men grabbed a Sabine women and ran off with them.

The legends say that Romulus and his motley crew were aggressive from day one, stealing women from their Sabine neighbours and immediately in conflict with the Etruscans and Latins. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian, wrote that the people captured in these conflicts were sometimes killed, sometimes enslaved and occasionally given citizenship. 14

Pragmatically, and not for the first or last time in their long history, Romans awarded citizenship to foreigners when it suited them.

Livy was underlining an important difference between Rome and most, if not all, of the rest of the ancient world. Many Greek city states fiercely protected their bloodlines and racial purity but Rome’s very foundation myth includes an open-door policy.

Rome’s earliest history is shrouded in myth and archeology is less helpful than might be expected given the continual process of development and renewal in a the city that has existed for over three millennium. But it is thought that the original Romans were probably Latin herders living in independent villages on the famous seven hills protected by the River Tiber and swampy lowlands.

The Etruscans were a sophisticated people who had developed in central Italy fin the Bronze Age. Their culture strongly influenced the Romans and they were finally absorbed in the Roman Republic and granted Roman Citizenship in 90 BC.

The Etruscans, a sophisticated culture to the north, took control of the area for around 250 years from around 750 BC until they were deposed in 509 BC and the first Republic was established.

The Roman Republic

The wonderfully named Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, or Tarquin the Proud, the last Etruscan King of Rome, was overthrown in 509 BC and the word “rex“, king, becomes an insult. Even when Rome and all its provinces came to be ruled by one man, an absolute ruler with limitless powers who held the role for life, albeit often a very short life, 17 the Romans went to great lengths never to suggest he was a king.

The word emperor, which is not latin but has come to mean ruler of an empire was derived from the latin word imperator, which means commander a title traditionally given to victorious generals and then to Augustus, the first “emperor”, and all who followed him. 18 The people we know as emperors were more likely to call themselves princeps, which in latin means the first or the most eminent and had been used in the Republic for the leader of the Senate, princeps senatus.

After the overthrow of Tarquin the Proud Rome was weak and threatened on all sides by more powerful cultures but despite this they expanded to take control of their neighbours and eventually the whole Italian peninsular.

This was never a foregone conclusion, Mary Beard points out that Rome’s neighbours were just as belligerent, militaristic and hungry for territory as the Romans but she believes a single decision changed the game. 19

Rome demanded that newly controlled territories, including those where control came about through alliance as opposed to warfare, provided, equipped and contributed to the command of troops that could be added to the Roman army. Whether this was a stroke of genius on someone’s part or a plan to avoid directly taxing the other cities in Italy it resulted in the Roman Army growing exponentially as each victory was won or alliance formed, and the new troops, and through them the new client cities, shared in the booty from the next victory.

By the end of the 4th century BC the Roman Army was nearly 500,000 strong; an incredible military force in the ancient world. Alexander had invaded Persia in 334 BC with only around 48,000 men.

It is beyond the scope of this essay to look in any detail at the Republic’s expansion but a succession of conflicts across the 2nd century BC resulted in Rome becoming the dominant power in the Mediterranean and in control of Macedonia, Greece and large parts of North Africa.

The Roman Republic ended when Octavian renamed himself as Augustus and princeps, the first man of the Senate, in 27 BC. The territory under Roman control already included Italy, Greece, the Iberian peninsular, all of Gaul, a large part of modern day Turkey and much of the Mediterranean coast of Africa.

This rapid expansion from an insignificant city recovering from having been sacked by the Gauls to dominating a large part of the known world was remarkable and not part of a master plan created in the 4th century BC. Taking control of Italy was partly defensive, a case at times of getting their retaliation in first, but it brought them in contact and then conflict with the Macedonian Greek world and with Carthage.

They had successes and failures but were belligerent and stubborn by nature and this somehow developed into expansionism. It is also worth recognising that wars are an opportunity for the elite and well connected parts of society to become wealthy and Rome was no exception in this regard. The state and its elite citizens amassed huge wealth through conquest and plunder before settling up provinces that returned taxes and raw materials to Rome whilst making their Roman governors rich.

High on the list of ways to benefit from conquest was the taking of slaves.

The First Slaves

These are clear references to slavery in the early Republic but it could be argued that there is little need to prove that slavery existed in 5th Century Rome as it would be far more surprising if it had not. Every other society around the Mediterranean owned slaves and some, like the Greeks, were utterly dependant upon them.

The early Romans had been ruled by Etruscan kings for two hundred and fifty years and there is no doubt that institutionalised slavery existed in Etruria. 20 I have discussed elsewhere that the Etruscans were heavily engaged in the wine for slaves trade with the Celtic inhabitants of Gaul long before Rome became powerful.

The earliest Roman laws that we know of are the Twelve Tables that date to around 450 BC. This first known codification of Roman law has not survived intact and our knowledge is based on later sources who had sight of the original laws. Slavery is not directly addressed in the Twelve Tables but there are some interesting mentions of slaves:

- It refers to the freedman Roman citizen, civis Romani liberti, a phrase that describes a manumitted slave; 22

- There is a stipulation that a person set free in a will on payment of a cash sum to the heir shall be freed even if the heir has sold the slave as long as the slave pays the specified amount to their buyer;

- If a slave is caught in the act of theft they are to be first flogged and then thrown from the Tarpeian Rock;

- If a person injures someone they would have to pay more compensation to a free person than to a slave;

- A slave cannot anoint a corpse.

The inclusion of these provisions indicates that as early as the 5th Century BC slavery was common enough to need certain forms of regulation. 23 Another sign that race was not a barrier to citizenship is evidence suggesting that they were awarding citizenship to freed slaves from as early as 357 BC when a manumission tax was instituted. 24

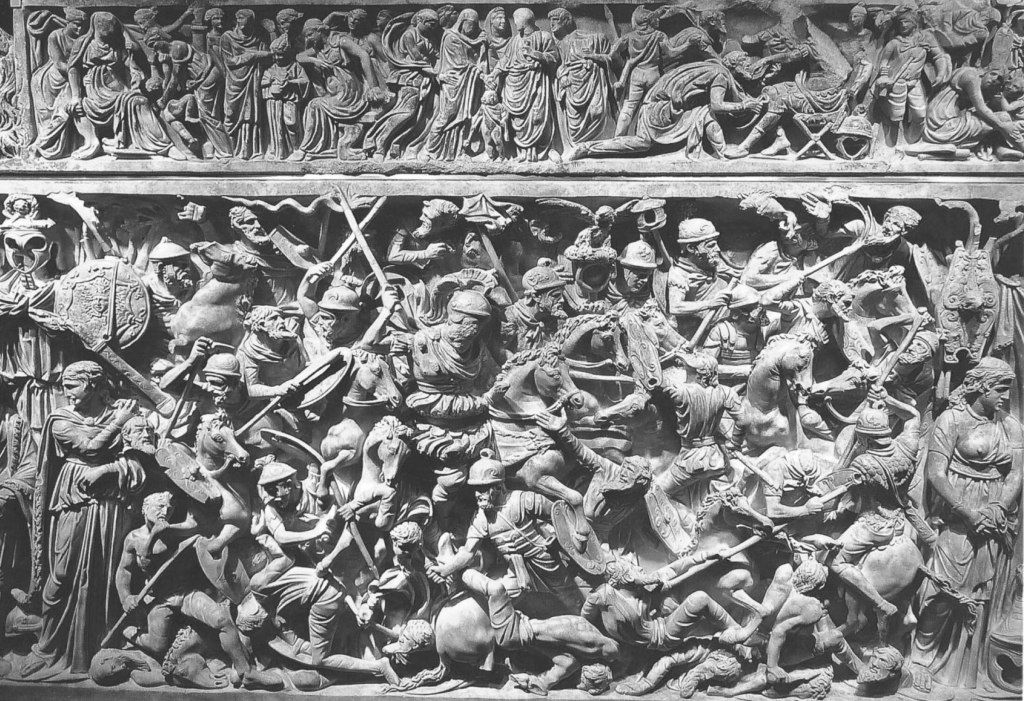

Slaves as the Spoils of War

Homer portrays the Trojan War as series of attacks on cities, Achilles boasts of sacking twenty three cities taking treasure, killing the men and enslaving the women; Odysseus sacks Ismaros on his way home and of course the war ends with the brutal sack of Troy.

Ancient writers often stop short of explaining the true meaning of the sack of a city, perhaps because their readers knew what it entailed, but an eye witness account from Polybius, who was with Scipio Africanus, at the siege of New Carthage in 209 BC wrote of how Scipio managed the sack of the city:

“When Scipio thought that a sufficient number of troops had entered (the city) he sent most of them, as is the Roman custom, against the inhabitants of the city with orders to kill all they encountered, sparing none, and not to start pillaging until the signal was given.

They do this, I think, to inspire terror, so that when towns are taken by the Romans one may often see not only the corpses of human beings, but dogs cut in half, and the dismembered limbs of other animals.

(After the city was surrendered), upon the signal being given, the massacre ceased and they began pillaging.”

Polybius goes on to describe how Scipio ordered part of the army to stay in their camp outside the city walls, keeps a 1,000 men with him in the citadel and orders the rest to start collecting the booty in the market place.

“Next day the booty, both the baggage of the troops in the Carthaginian service and the household stuff of the townsmen and working classes, having been collected in the market, was divided by the tribunes among the legions on the usual system.” 27

Two things stand out in this description, it shows the Roman Army of the Republic as a highly disciplined and well organised machine; and the phrase “as is the Roman custom” suggests that this methodical approach to sacking a city was the protocol at that time.

Polybius writes at some length about the advantages of this system whereby half the army guards the other half while it pillages a city knowing that they will receive their fair share when the spoils are divided.

Scipio ordered his soldiers to bring the surviving population of Carthage, around 10,000 people to the market and to divide the women and children from the “working men”. The women and children were told to return to their homes and the men were instructed to register as state owned slaves who were to continue in their trades but now on behalf of Rome.

Some, the strongest, were assigned to as oarsmen to man the captured Carthaginian galleys. Scipio promised the slaves their freedom when the war with Carthage was successfully concluded but whether this was in 201 BC at the end of the 2nd Punic War or if it happened at all is not recorded.

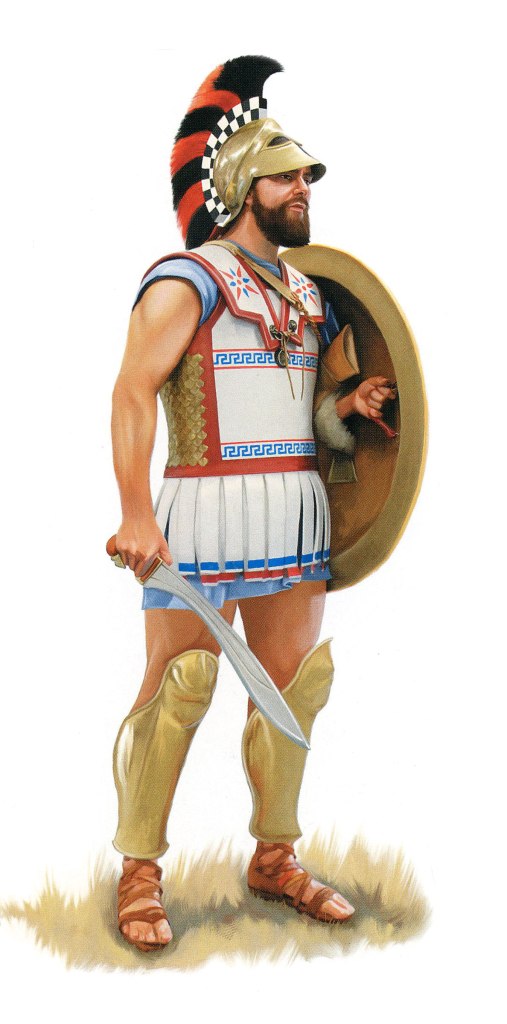

Above: Centurion at the time of the Punic wars 28

Tragically, the sacking of cities had been seen as the soldiers’ prerogative for as long as cities have had defences and resisted conquest. For much of the last 4,000 years it was the inevitable outcome of defeat. Rome itself was sacked at least seven or eight times.

Etruscan and Latin Wars

In around 503 or 502 BC, just seven years after the overthrow of the Etruscan kings Pometia and Cora, two Latin settlements south of Rome, left Rome’s sphere of influence to join the Aurunci, the people occupying the southern border of the Latini.

Rome went to war with the Aurunci; Livy wrote of several battles and failed sieges of Pometia but eventually the town surrendered.

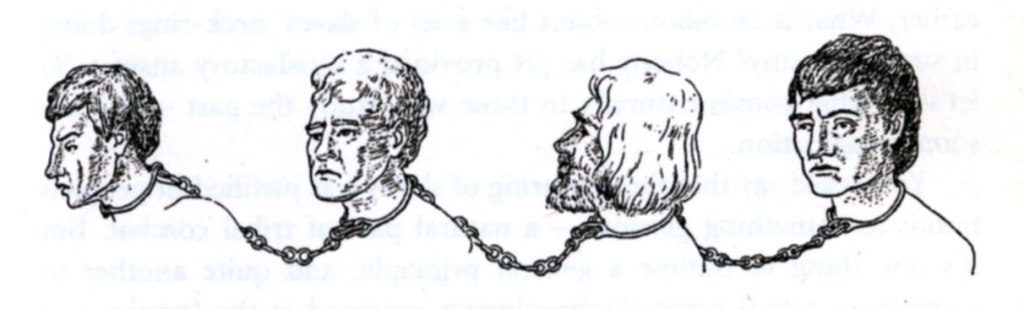

Right: slaves in chains from Smyrna. 30

Livy reports:

“Yet though the town had surrendered, the leading men of the Auruncians, with no less cruelty than if it had been taken by assault, were beheaded indiscriminately; the others who were colonists were sold by auction, the town was razed, and the land sold.”

In 468 BC the Roman Consul Titus Quinctius Capitolinus Barbatus besieged and captured Antium, modern day Anzio, the main stronghold of the Volsci people. After the town was taken its leaders were beheaded and its citizens sold into slavery. A pattern was emerging that when a city was sacked the soldiers could keep all the booty except for precious metals and captives, these were claimed by the state. 31

In 438 BC Fidenae, a town so close to central Rome that it is now inside the Grande Raccordo Anulare, 32 switched allegiance from Rome to Veii, an Etruscan City a little further away. Following two battles, one at Anio and one at Fidenae the Romans prevailed and killed the Etruscan King Tolumnius. After the battle each centurion and cavalryman was given a captive as a slave and the remaining captives were sold as slaves by the state.

Veii was just 16 kilometres from Rome on the other side of the Tiber, just a little further away than Fidenae. Rome and Veii had been rivals since the early days of the Republic with both cities wanting control of the salt pans at the mouth of the Tiber and to hold the greatest influence over the less powerful towns in the area. Livy wrote that war was declared in 406 BC 33 but historians wonder if this was a piece of reverse engineering so victory in 396 BC conveniently followed a ten year war thus matching the length of Homer’s Trojan war.

Above: Etruscan warrior showing the Greek influence of their armour 34

The war concluded with the Romans sacking Veii in around 396 BC. Livy wrote of the aftermath of a typically violent and bloody end to the siege:

At length, after great carnage, the fighting slackened, and the Dictator [Marcus Furius Camillus] ordered the heralds to proclaim that the unarmed were to be spared.

The following day the Dictator sold all freemen who had been spared, as slaves. 35

There is some evidence that a large number of people became citizens around this time and it is possible that, despite Livy’s commentary above, this was the majority of the population of Veii, 36 a further example of Rome’s pragmatic approach to citizenship and the need to form stable, local alliances.

The wars between Rome and the Etruscans, continued on and off for over 200 years until Etruscan resistance was finally crushed in 264 BC.

Samnite Wars

As well as nearly continuous disputes with the Etruscans the Roman Republic engaged in three wars with the Samnites, who occupied much of modern day Abruzzo and Puglia and the Apennine mountains that form the spine of Italy. The first of three wars broke out in 343 BC when the Samnites attacked Teanum Sidicinum in Campania and lasted until 342 BC, the second war ran from 326 to 304 BC and the third from 298 until 290 BC.

Large numbers of captives were taken from the Samnites, Etruscans, Sabines, Umbrians and Gauls during these years. For the third Samnite War alone Livy recorded nearly 74,000 captives.

It is thought that in 265 BC, long after the Latin and Samnite Wars had ended the total population in the area controlled by the Republic was around 1.2 million 37 and in that context 74,000 captives even spread across seven years is, in the true sense of the word, incredible. For every captive there was often a dead Samnite, Etruscan or Umbrian quite apart from any Roman casualties.

Above: 4th century Roman legionnaire 38

Livy never mentions non combatants in the form of women, children and slaves who we can assume was also enslaved.

Taking Livy’s numbers and adding non combatants we reach in excess of 100,000 and perhaps as many as 150,000 slaves being absorbed into the Republic’s economy in six or seven years.

Pyrrhic War

Between the end of the Samnite Wars and the Pyrrhic War Rome finally subdued the Etruscans, devastated southern Cisalpine Gaul and laid claim to much of what we now know as northern Italy. In doing so they continued to enslave the survivors.

The Romans were now one of three major powers in the Mediterranean; the Greeks with their colonies across the south of Italy, Magna Graecia, and the Carthaginians who from their homeland in modern day Tunisia had developed colonies across most of North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and southern Spain.

It was now inevitable that Rome would come into conflict with both. Livy, who remains the best source for this period, always suggests that Rome is acting in self defence but it is difficult to justify that position.

In 282 BC Rome send ten warships to Tarentum in breach of a treaty probably signed in 332 BC. Tarentum was an important Greek colony with an excellent harbour in modern day Apulia. The Tarrentines were provoked into attacking the ships and then attacked a Roman garrison at Thurii. The Romans retaliated by invading and the Tarrentines hired King Pyrrhus of Epirus to come to their aid.

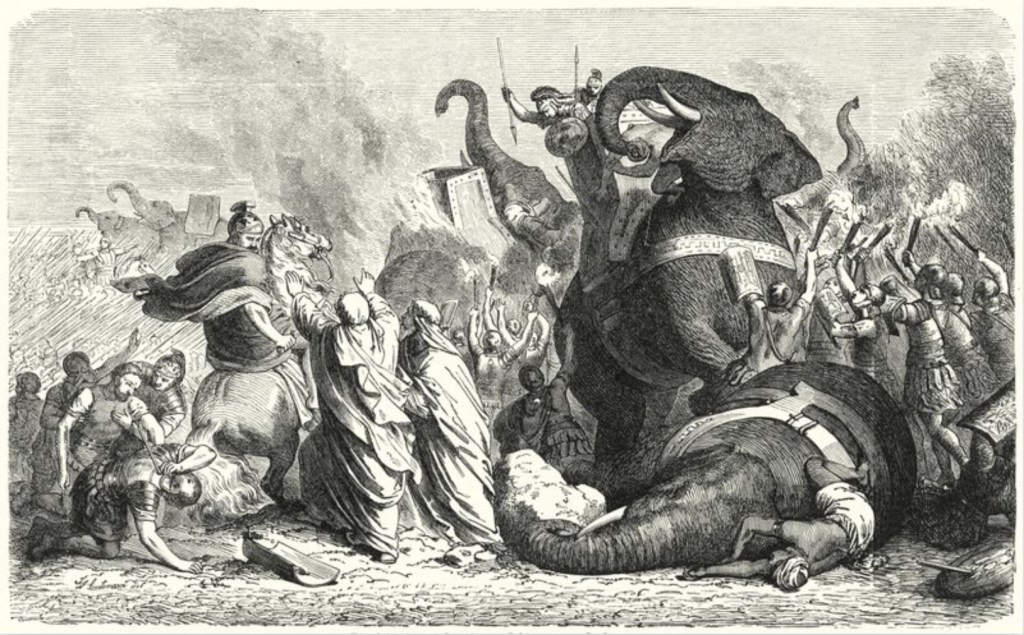

Pyrrhus was a famous mercenary leader whom Hannibal is reputed to have considered the greatest general since Alexander the Great. He arrived in Italy with 20,000 infantrymen, 3,000 cavalry, 2,500 skirmishers, and 20 elephants.

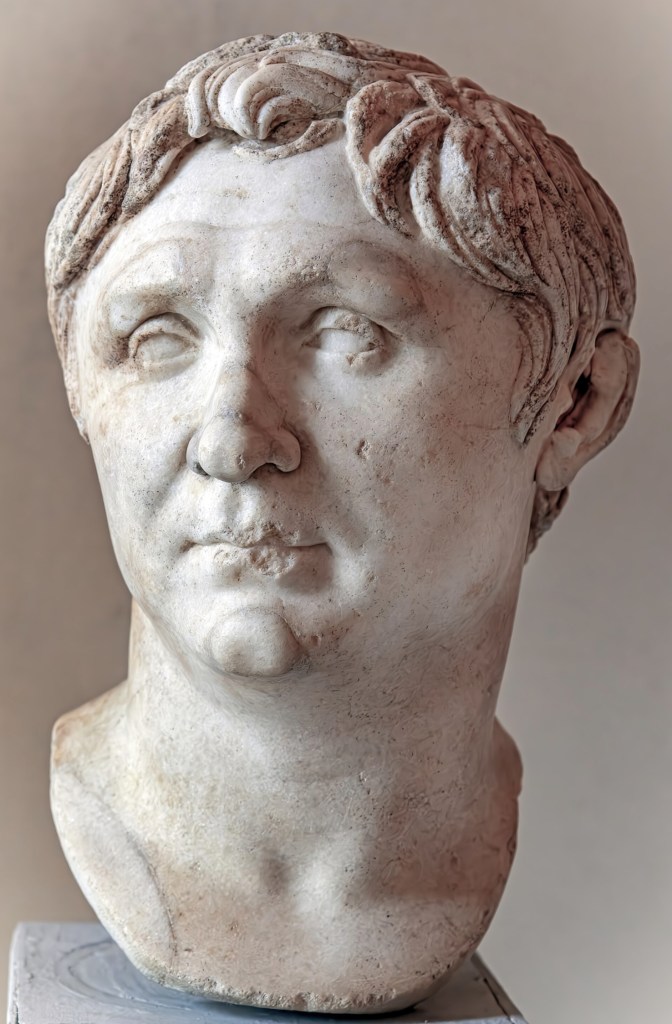

A bust of Pyrrhus was found in a villa outside Herculaneum 39 (see right) and is thought to be based on a sculpture made during his lifetime.

Mary Beard argues that he is the first person in Roman history whose real face is known to us. 40

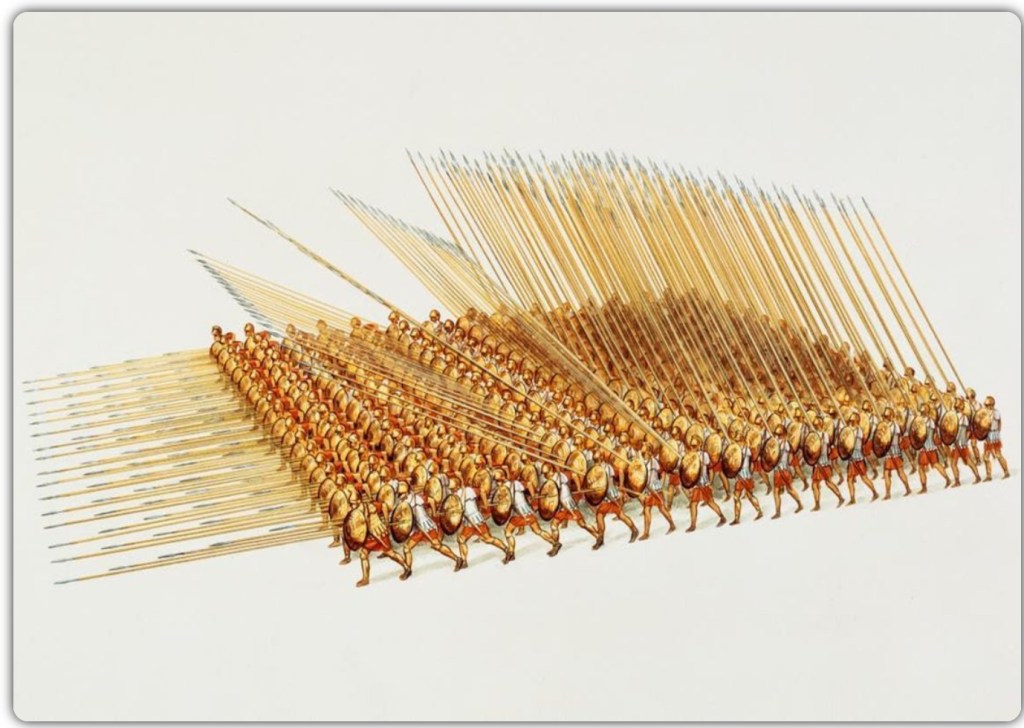

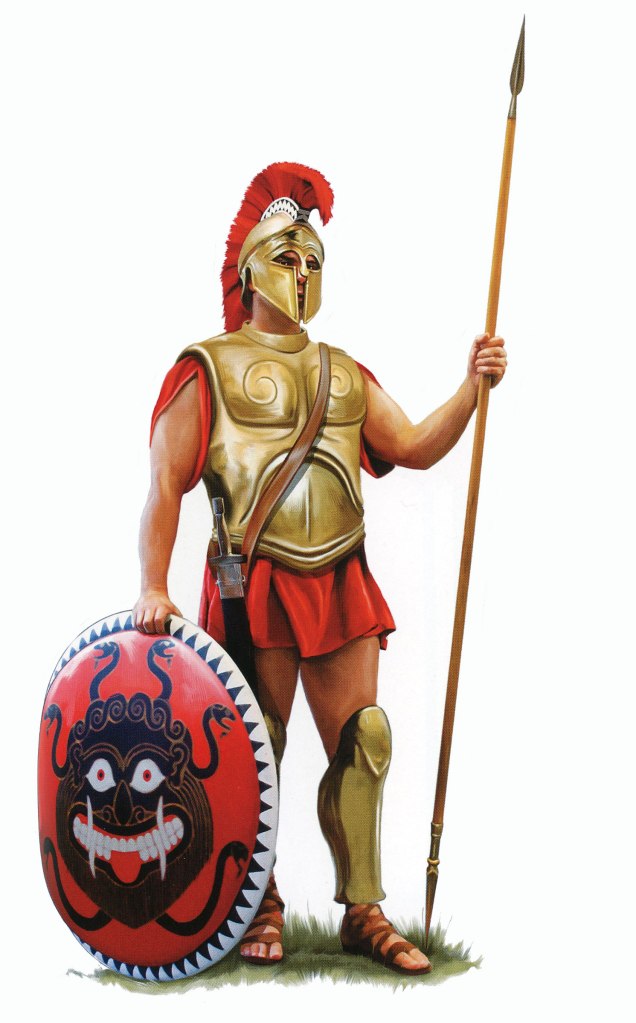

His infantry were mostly phalangites, trained professional soldiers who stood twelve deep in the line of battle, the phalanx, armed with a four and half metre spear or sarissa. The Romans despatched the consul Publius Valerius Laevinus with 35,000 troops to confront Pyrrhus but were routed by his elephants at the Battle of Heraclea in 280 BC. The next year an even larger Roman army was defeated at Asculum and it was not until the Battle of Beneventum that the Roman legions prevailed and Pyrrhus withdrew to Epirus.

Above: A hoplite who would have fought in a Phalanx 41

The Romans absorbed the Greek colonies into their sphere of influence. The legions, which were still an army of citizens called up as necessary, were now battle hardened and confident having progressed from beating citizen armies put into the field by city states or Celtic tribes to defeating a well-led professional army equipped with the two great weapons of the age, the phalanx and the elephant. Rome was ready to expand outside of Italy.

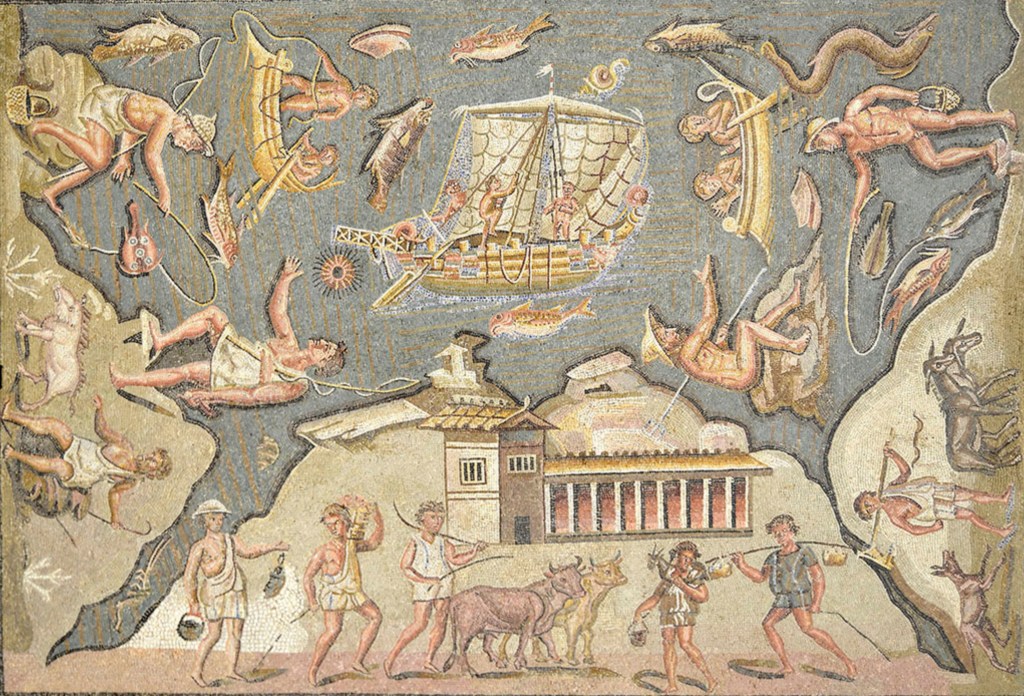

The Era of the Punic Wars

From the end of the Pyrrhic War, which was quickly followed by the first war against Carthage until the end of the Republic in 27 BC Rome is nearly constantly at war. Wars that make them not just the most powerful of the ancient civilisations but also the richest with plunder pouring back into Rome to be housed in the state treasury under the Temple of Saturn and plenty of cash in the pockets of the soldiery.

In contrast to the wars against their close Italian neighbours Rome was now often fighting powerful enemies with thriving economies of their own. The net result being far more people to be captured and carried off. At Agrigentum in 262 BC, the ancient Greek colony of Akragas in western Sicily, the Romans chased off a Carthaginian army and sacked the city taking 25,000 captives.

After winning the sea Battle of Cape Ecnomus in 256 BC the Roman Army established a beachhead on the shores of Africa. They plundered the surrounding countryside capturing and enslaving 20,000 people. The fleet left part of the Army in Africa and returned to Rome with 27,000 captives.

To put this in perspective Cato the Elder who died in 149 BC and who was known to like young war slaves was willing to pay 500 to 1,500 denarii for a slave. This price for an “ordinary” slave increased significantly if the slave attracted particular buyers, so for example, a pretty female slave would sell for between 2,000 and 6000 denarii.

At an average of say 1,000 denarii per slave the state’s income from the sale of slaves after the battle of Cape Ecnomus could easily have been 3 million denarii, which today would be somewhere in the region of £200 million. 44

Throughout the Punic war and the various conflicts with the Gauls in the same era the number of captives after single battles, sieges or campaigns is staggering; tens of thousands of people enslaved time and time again. When Carthage is captured in 209 BC the number of captives could have been as high as 25,000, when Tarentum which had fallen into Carthaginian hands fell another 30,000 slaves were taken and the following year 12,000 Carthaginian soldiers were captured.

Above: Carthaginian war elephant 45

The final battle of the Punic wars was on the plains of Zama in 202 BC where Scipio defeated Hannibal and sacked his camp taking great riches back to Rome, riches including all the loot Hannibal had plundered in his campaign in Italy. Along with the loot as many as another 20,000 soldiers were enslaved.

An example of the the aftermath of these sieges and battles is given by Didodorus Siculius in History of the World, in 254 BC the Romans took Panoramas, modern Palermo in Sicily:

“The Romans dropped anchor in the harbour, close to the walls of the city and disembarked their military forces. They built a palisade and a ditch to put the city under siege…….. then they made continuous assaults with their siege machines and finally broke down the wall. When they gained control of the outer part of the city, they killed many people.

The survivors fled to the heart of the city and sent ambassadors to the consuls to ask that their lives be spared. They agreed that those people who paid two minae [100 denarii – about £7,000] each would go free; then the Romans took possession of the city.

Fourteen thousand people found the money and met the terms of the agreement and were released. The rest, thirteen thousand in number, were sold by the Romans as booty along with the other loot.”

We cannot know to what degree the ancient historians exaggerated the number of captives but we can be sure that large numbers of slaves found their way to the slave markets from the Punic wars and their subsequent sale continued to swell the coffers of an already very rich city.

Wars with Macedonia, Greece, Spain and the Gauls

The Romans subdued Philip of Macedonian after the second Macedonian war in 197 BC and made the Greek cities he had previously controlled autonomous. The slave markets in Macedonian and Greece were only too happy to absorb a few thousand war captives.

As they worked their way through the Greek world taking city after city with, according to the ancient historians, around 5,000 captives each time there are occasionally reports of large numbers of captives.

Gnaeus Manlius Vulso defeated the Galatian Gauls in northwest Anatolia in 189 BC taking 40,000 captives but it seems he had to leave them with local tribes.

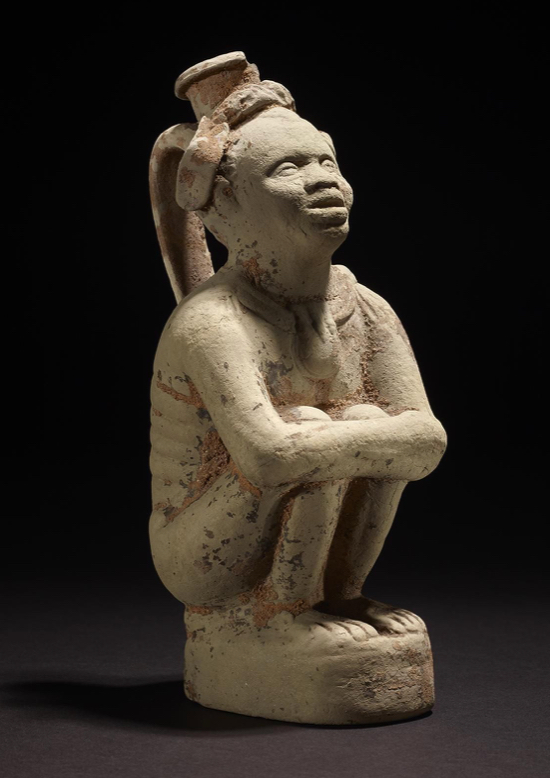

Left: A Gaulish mercenary found in Ptolemaic Egypt 220 BC 46

Marcus Popillius Laenas campaigned in northern Italy in 173 BC and was said to have sold 10,000 Ligurians after they had surrendered but the Senate noticed that they were Ligurians who had not taken up arms against Rome and he had to give them back their freedom and the property he had stolen from them.

Across Epirus in 167 BC the Romans were said to have sacked 70 towns or cities and taken away 150,000 captives and after their sale the legionnaires were given 200 denarii and the cavalrymen 400 denarii each, around a years wages.

The total number of slaves taken in war in the first 350 years of the Republic is unknown but there are dozens of battles where the ancient historians report “5,000” or a similar round number and if we add the occasions when they appear to be more specific it suggests that the average number taken per battle was non-trivial.

However, some estimates are shocking; According to Plutarch 47 Gaius Julius Caesar, killed one million Gauls and enslaved another million between 58 and 50 BC.

Left: Gaulish prisoner with his hands tied behind his back. 48

In 57 BC Caesar is alleged to have sold 53,000 members of the Atuatuci tribe to slave dealers in a single day and in 52 BC after the Battle of Alesia he gave one gallic captive to each of his 80,000 soldiers. 49

Number of War Slaves in the Days of the Republic

At the end of his excellent and very detailed study of war slaves in Republican Rome Jason Wickham 50 comes up with a summary based on the original sources but factored to neutralise, what he sees as, unrealistic estimates by the ancient historians.

| Years BC | Slave Pop. of Rome | Need to add 6% per annum | Annual War Captives High Estimate | Annual War Captives Low Estimate | % Contrib. to Need |

| 299 – 250 | 262,000 | 15,720 | 5,000 | 2,500 | 28 -16% |

| 249 – 200 | 354,000 | 21,240 | 6,000 | 3,500 | 28 -16% |

| 199 – 150 | 478,000 | 28,680 | 7,000 | 3,000 | 24 – 11% |

| 149 – 100 | 645,000 | 38,700 | 8,000 | 4,000 | 21 – 10% |

| 99 -50 | 870,000 | 52,200 | 22,000 | 8,000 | 42 – 15% |

| Total | 2.4 Million | 1.05 Million |

Wickham argues that war slaves were only supplying a fraction of the demand in Rome but even his low estimate proposes over a million people enslaved by Rome in the course of their endless wars. 51 Despite the long period this survey covers it remains a chilling number.

War Slaves in the Imperial Age

Some historians believe that war slaves became less important in the Imperial Age but this may be a too simplistic view of slave supply. Home-born slaves, cross border trading and piracy all played significant roles in the Imperial Age, just as they had in the Republic, but Rome also continued to be engaged in conflicts and bringing home war slaves in the early years of empire and even after the empire was at its largest in AD 117.

The Jewish war in AD 66 to 70 like so many of Rome’s wars led to large numbers of slaves; 2,130 women and children at Japha, 30,400 prisoners at Tiberias and a staggering 97,000 people enslaved after the siege of Jerusalem. It is thought that over a million non-combatants died in the Jewish war and it is possible that the total deaths and prisoners taken represented as much as a quarter of Judaea’s population.

The emperor Trajan was involved in three major wars during his 19 year reign; two against the Dacians and one on the eastern frontier.

In AD 101 he defeated the Dacians at Tapae but they rose again and he returned in 105 to destroy them once and for all. After defeating their king in battle he proceeded to Sazmizegethusa, confiscated their treasury and enslaved 500,000 people.

Septimius Severus was emperor from AD 193 to 211 and is often referred to as the African emperor as he was born in Leptis Magna in modern Libya. In 197 he defended Mesopotamia from the Parthians and in 198 enslaved 100,000 people when he took the city of Ctesiphon in modern Iraq.

In terms of land mass the Empire reached its zenith in AD 117 when the newly established Emperor Hadrian fixed Rome’s borders and stopped attempts to expand in the east and north.; there were a number of wars and military adventures after this date but no more significant land grabs leading to large numbers of prisoners of war.

There may have been the beginnings of a different approach to prisoners of war in the late 2nd century. Marcus Aurelius, a stoic philosopher and the last of so-called “five good emperors”, was engaged for most of his reign in the Marcomannic Wars that lasted from AD 166 to 180. these were wars against German, Sarmatian and Gothic tribes along Rome’s northeastern borders.

These wars involved large numbers of legionnaires and tribesmen and must have resulted in a significant number of prisoners of war but for the first time instead of enslaving all their captives Marcus Aurelius ordered some to be settled, along with their families, in Dacia, Pannonia, Moesia, Germania and even some near Ravenna in Italy 54. They were settled as colini (singular colonus), tenant farmers working land they did not own and paying rent in the form of produce or service. 55

This approach became more common in the 3rd and 4th centuries; Emperor Constantius Chlorus in 297 sent Chamavi and Frisians as coloni to “desolate lands” in Gaul and other places. 56

Other Sources of Slaves

The supply of prisoners of war might have dwindled towards the end of the 2nd century but the demand for slaves remained strong until at least the 4th century.

Along with becoming a prisoners of war there had always been six other ways to become a slave in Rome:

- Captured outside the Empire as part if the frontier slave trade;

- Captured by pirates and brigands but not necessarily outside the Empire;

- House born meaning born to a female slave in her master’s house;

- Abandoned Infants raised as slaves alongside house born infants;

- Sold into slavery by your family

- Self Enslaved

Prisoners of war had been an important part of the supply but all the other sources had been in existence through the days of the Republic and carried on in the Imperial Age. Trading in slaves was lucrative and although the Roman elite looked down on all trade many openly or surreptitiously engaged in slave trading.

Persius, a satirist in Vespasian’s day, said that slave trading was the quickest way to double one’s money and Cicero commented on the preeminent wealth of slave traders. 57 It would take a seismic shift in the way the Roman world operated before demand and therefore the profit opportunity diminished.

Frontier Slave Trade

As previously discussed (here) the Romans, from their frontier settlements along the borders of the Empire, traded wine for slaves at an exchange rate of one amphora of wine for one slave; a slave who could be sold back in Rome for the equivalent of 6 or 7 amphora of wine.

They had inherited this lucrative trade from the Greeks and Etruscans who had been trading in this manner ever since the Greeks founded Marsalis on the southern coast of Gaul in 600 BC.

Before the Gallic wars around 15,000 Gaulish slaves a year 58 were sent to the markets in Rome and in exchange the tribal leaders on the borders between the Mediterranean and Celtic worlds acquired luxury goods and wine, lots of wine. Over time these chieftains became increasingly Romanised in their tastes and habits, often building Roman style houses with heated dining rooms where Italian wines could be drunk in elegant and fashionable surroundings.

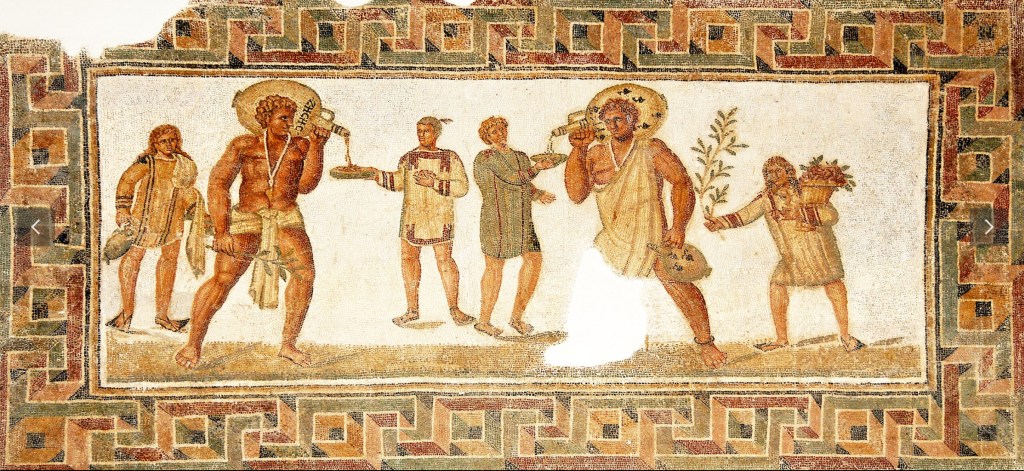

Above: Gravestone from Nickenich near Mayen, Germany dated to c. 50 AD. The relief shows a slave trader leading two slaves on a chain. 59

They became the interface between the Roman traders and tribes in the interior but rather than dealing directly with those tribes they dealt with entrepreneurial, and highly mobile, middle-men.

When Gaius Julius Caesar brutally dragged Gaul into Empire between 50 and 58 BC and then again when the Emperor Claudius invaded Britain in 43 AD the frontier moved north and west but the system remained in place.

Wherever the frontier was established the slave traders were there to offer wine to the tribes just across the border who, in turn, became slave hunters and traders themselves or established an infrastructure to entice other tribes to hunt, capture and bring slaves to their settlements conveniently located just outside the Empire.

Rome was a vortex that sucked in slaves from far outside its borders.

When the Empire was at its largest extent slaves were being imported from Ireland, Scotland, the Eastern European countries bordering the Rhine and Danube, around the Black Sea, the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa.

Left: an African slave for sale. Campania 1st century BC. 60

There are a small number of archeological finds that provide potential insights to the Roman slave trade.

In 2015 the remains of a man were found in ditch in Great Casterton in central England. His remains have been dated to between AD 226 and 427 and remarkably he was placed in the ditch wearing heavy iron shackles padlocked around his ankles. 61

These type of shackles have been associated with slavery elsewhere in the Roman Empire so there is an assumption that this man, who was between 26 and 35 years old was a slave. His skeleton shows signs of a hard life so it is likely that he had been a slave for some years before his death. We cannot know whether he was being moved by his owner or a slave trader or how he met his death.

In October 1942, at the height of the War in the Atlantic, RAF Rhosneigr, a WWII airfield was being extended. The construction work turned up a well made, 3 metre long, iron chain that over time led to further searches and excavations that, in turn, led to the discovery of 150 items that form, what is known as, the Llyn Cerrig Bach hoard.

Within the hoard there were two chains. They were made with great skill and craftsmanship and deposited in the lake around 100 BC. One chain has four and the other five neck rings separated by about 1/2 a metre of heavy chain. Their purpose was to shackle slaves and are designed to allow individuals to be added or removed from the group.

The function of the chains is obvious and we can speculate that they were part of the standard equipment of a slave trader operating in Britain before the Roman conquest but perhaps in the business of taking slaves to sell to Roman traders or Celtic middle-men.

The Llyn Cerrig Bach chains are not unique. These Iron Age Shackles probably connected to the Roman slave trade were found at Bigbury Camp near Canterbury in Kent. 64

The two images above show small figurines of bound people and are dated to the 2nd or 3rd century AD. Similar figurines have been found across Britain and on the Roman Rhine/Danube frontier. Each figurine has a flat back and a round hole through their midriff so it is probable that they were originally mounted in some way. It is suggested that they depict slaves and are in some way connected to the slave trade. 65

The ancient writers make few references to the slave trade and how it operated but Saint Augustine writing in the 5th century describes the slave trade in the Roman province of Africa, modern Tunisia and parts of Algeria and Libya:

There is in Africa such a great multitude of men who are commonly called slave merchants that they seem to drain this land to a large extent of its human population by transferring those whom they buy—almost all of them free men—to the provinces overseas.

For scarcely a few are found to have been sold by their parents, and they do not buy these, as the laws of Rome allow, for work lasting twenty-five years, but they buy them precisely as slaves and sell them overseas as slaves. 67

Augustine goes on to say that the slave merchants were also supplied by slave raiders who probably worked both sides of the border areas capturing children. This was common enough for the Emperors Caracalla and Constantine to legislate that anyone caught stealing children for the slave trade would be sent to the mines for life. 68

Pirates and Brigands

Cilicia in southern Anatolia was well known as a base for pirates from the 2nd century BC until Pompey suppressed them in 67 to 66 BC.

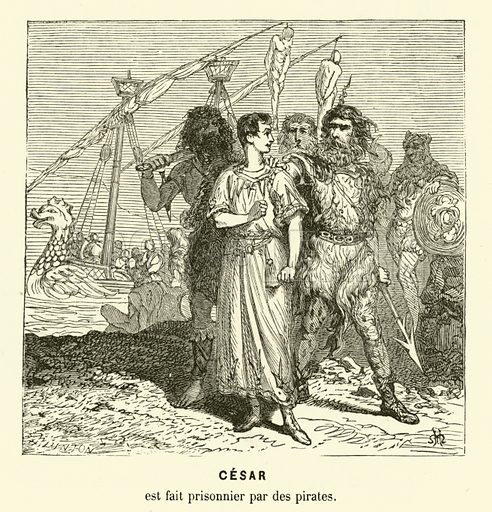

Julius Caesar was famously captured in 75 BC (left) but this did not turn out well for the pirates as after he was ransomed he raised a naval force, captured the pirates and crucified them. 69

The Romans were a land-based power so after Carthage had been defeated and the Seleucid Empire was forced to give up its fleet the Mediterranean became increasingly lawless. Along with the Cilicians the Cretans had turned to piracy and nearly all coastal towns and villages were vulnerable to being raided.

The pirates were not only capturing people living near the coast but were organised and powerful enough to raid inland. The slave market at Delos was conveniently situated in the centre of the Aegean and it was there that most captives were taken.

Ostia, the port of Rome, was attacked in 67 BC and a Roman fleet that had been assembled to hunt pirates was burnt or captured and two senators held to ransom.

This was seen as an outrage and by now the pirates were threatening the grain ships arriving from Egypt so Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Pompey the Great (right) , was given unprecedented powers and despatched on a three year mission to solve the problem.

His mission was a huge success and in just a few months the pirates had been beaten at sea and on land but the turmoil in Rome after Caesar’s assassination allowed their resurgence. With Delos no longer a major trading centre the Cilician pirates were now running their slave trade from Side.

Pirates were an important part of the slave supply chain and only drove the Romans to act when they threatened the grain supply or sided with Rome’s enemies. All the time they stuck to their trade of raiding towns and villages far from Rome and selling slaves to Roman traders they were tolerated.

The empire was never an entirely safe place for travellers and, even travellers in Italy were know to mysteriously disappear. Paul the Apostle, who was traveling around the empire in the 1st century wrote in Corinthians :

“Three times I was beaten with rods, once I was pelted with stones, three times I was shipwrecked, I spent a night and a day in the open sea, I have been constantly on the move.

I have been in danger from rivers, in danger from bandits, in danger from my fellow Jews, in danger from Gentiles; in danger in the city, in danger in the country, in danger at sea; and in danger from false believers.

I have laboured and toiled and have often gone without sleep; I have known hunger and thirst and have often gone without food; I have been cold and naked.” 70

Banditry was a serious threat to travellers across the whole empire. Augustus made attempts to suppress it and as a consequence there was less risk in the 1st century AD but before and after this time travel was a precarious business. Bandits operated in remote rural areas and on the fringes of the empire, or at the borders of two different administrations so they could slip back and forth between jurisdictions. As with any society many of the people who resorted to banditry were poor, dispossessed or runaway slaves.

The legend of Bulla Felix, “Lucky Charm”, Rome’s version of Robin Hood, was reputed to have operated from the forests outside Rome in the 2nd century AD. He is alleged to have written to the emperor Septimius Severus saying that, if he wanted to suppress banditry, he needed to improve the treatment of slaves and the poor. 72 Whether Bulla Felix existed or not the threat to travellers was very real; the rich could afford to travel with guards but for many people they took the risk of being robbed or captured and to be either ransomed or enslaved and sold.

How many slaves entered the open market through banditry is unclear, it seems unlikely that this was possible in settled parts of the empire but banditry probably played a significant role on the northern, eastern and southern borders where cross border raids to capture barbarians for the slave trade could easily disguise raids on settlements inside the borders of the empire.

The Greek historian Cassius Dio suggest that this was happening in Britain when he described the people living either side of Hadrian’s wall:

“There are two principal descent groups of the Britons, the Kaledonians and the Maiatians, and the names of the others have been merged into these two.

The Maiatians live next to the cross-wall which cuts the island in half, and the Kaledonians are beyond them. Both of these inhabit wild and waterless mountains and desolate and swampy plains. They possess neither walls and cities, nor tilled fields. Instead, they live on their flocks, wild game, and certain fruits.

They do not touch the fish which are found in immense and inexhaustible quantities there. They live in tents, naked and without foot-wear, and they possess their women in common and raise their children in common.

They have rule by the people for the most part, and they enjoy engaging in banditry. Consequently, they choose their boldest men as rulers. 73

House Born

House bred or home born slaves (verna, plural vernae) were slaves born in the master’s house and the easiest way to become a slave.

Given the slave population the number of children born into slavery was a significant contributor to the supply of slaves and may have become the major source when the empire stopped expanding through conquest. 74

Some Romans insisted that all their domestic staff were vernae as those born into slavery were they thought to be less intractable. 75

It should come as no surprise that Varro (116 to 27 BC), in his extensive guide to managing an agricultural estate, gives specific advice on breeding vernae. He believes best practice is to give herdsmen female companions that are kept on the estate with their children when the herds go to their summer grazing to ensure the herdsmen return with the herd.

In addition Varro suggests providing, presumably other, female companions to go with the to cook for the shepherds and to spend the summer producing vernae to add to the estate’s slave population. 76

It is a chilling thought that the farmer hoped that both the sheep and the female slaves he had sent with the flock returned pregnant in the Autumn.

Left: Statuette of the Good Shepard, 18th C. rework of a fragment from a sarcophagus. 77

Varro also proposed providing a male slave with a female companion as a reward or as a perk of seniority:

“You should make your foreman more eager to work by giving them rewards and by seeing that they have a peculium 78, and female companions from among their fellow slaves, who will bear them children.”

Plutarch wrote that Cato 79 used sex as a way of controlling his slaves:

“Since he believed that the main reason slaves misbehaved was their sexual frustration, he arranged for his male slaves to have intercourse with his female slaves….” 80

Columella (4 to 70 AD) 81 rewarded women who produced vernae:

“To women, too, who are unusually prolific, and who ought to be rewarded for the bearing of a certain number of offspring, I have granted exemption from work and sometimes even freedom after they had reared many children. For to a mother of three sons, exemption from work was granted; to a mother of more, her freedom as well.” 82

Of course, the children would belong to the slave’s master but there was a small twist in that Roman law followed the principle of partus ventrem sequitur (offspring follow the womb) which meant a child born to a slave woman was a slave regardless of the father’s status and a child born to a free woman was born free regardless of the father. 83

It was not until between the middle of the 5th century 84 that it became illegal to separate slave families so until that point an owner was within their rights to sell the children of slaves or to sell either the mother or father separately.

Abandoned Infants

In an age when herbal and folk remedies were the only known methods of contraception and abortion was a highly dangerous option there would have been many unplanned and unwanted pregnancies and births. Even when the child was born into a stable family baby girls were at risk of being abandoned by families with modest incomes as dowries would have been expensive if the child survived into adolescence.

Abandoning or exposing unwanted babies was practiced across the whole social spectrum. When a baby was born the midwife placed the child on the ground and only if the paterfamilias picked it up was the baby deemed to be part of the family. Deformed babies were usually exposed as a matter of course but depending on their impairment might still have been taken and raised as slaves.

There were places in Rome that were well-known as locations for abandoning unwanted babies. Slave dealers watched these places and paid lactating women to feed them.

The child was normally raised for four to five years before being sold. 86

Left: Saturnia tellus, panel from Altar of Augustan Peace 1st century 87

The number of abandoned children is unknown but it was common enough to create problems for administrators who had to deal with slaves claiming to have been born free and raised as a slave. When Pliny was governor of Bithynia it was so common he wrote to the Emperor Trajan asking for advice on how to handle the cases he was dealing with. Trajan was not much help but admitted it was a common problem across the empire. 88

Sold by Your own family

At every level of Roman society the head of the family, the paterfamilias, had absolute power over his wife, children and slaves. Only the paterfamilias could own property and he had the legal right to disown or kill his children but until AD 312 there were laws that prevented selling a Roman citizen

After AD 312 when the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity exposing and abandoning children was forbidden but parents were then allowed to sell their children into long-term, twenty five year, indenture, so, effectively into slavery.

Until AD 212 the majority of people living in the empire were not Roman citizens so a law preventing the sale of citizens didi not apply. As a result it was not uncommon for non-citizens, especially on the fringes of the empire to sell their children into slavery. This may have changed when the Emperor Caracalla grated citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire but the empire was huge and impoverished families would still have turned to slave traders in times of need.

An unpleasant twist on the “sold by your family” category of slaves is the story of the Frisii, a tribe who live where the borders of Holland and Germany are today.

Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus (right) , the younger brother of the emperor Tiberius, was a successful Roman General who was well on the way to bringing all the German tribes into the Empire when he fell from his horse and died in AD 9 near the Elbe River. He had been campaigning in Germany since 12 AD and had subdued the Frisii, Chauci, Cherusci and Chatti tribes.

Drusus had imposed a moderate tax on the Frisii but a later governor increased the tax and when it was not paid he first decimated, that is took 1/10th of, their cattle herds, then confiscated their land and finally took their women and children as slaves. The Frisii rose up, killed the tax collectors and laid siege to the local Roman fort.

In 28 AD the legate Lucius Apronius raised the siege but was defeated by the Frisii at the Battle of Baduhenna Wood, 400 Roman soldiers committed suicide rather than be captured by the German tribe. 89 The fate of women and children is not recorded.

Self Enslaved

During the early days of the Republic there was a legal contract, nexum, that involved the loan of money using the lender, on one of his sons, as collateral. It is unclear whether the system entailed becoming a slave for a certain period in return for receiving a loan or whether the lender became a slave if they failed to repay the loan. The enslaved debtor remained a Roman citizen and could not be sold or moved elsewhere by the lender.

It was repealed in 326 BC and all insolvent debtors were freed. There was then a lengthy period when citizens could not fall into slavery but it became common again in the final days of the empire.

Conclusion

When researching slavery, especially the East African slave trade of the 17th and 18th centuries the challenge is the lack of sources. The challenge with looking at the Romans is being overwhelmed by the available material. If you are interested in the Romans in general but don’t know where to start I’d recommend Mary Beard and Guy de la Bédoyére, both are brilliant scholars who write for us ordinary folk, their books are not just sources of information but full of wit and insightful comment.

This essay, part 5 of my history of slavery, has mostly focussed on the sources of slaves in the Roman world. The next two essays will deal with:

- Part 6 – Slave Ownership, Markets and Traders

- Part 7 – Slaves and Work

Leave a reply to A History of Slavery Part 7 The Romans: Slaves and Work – Travelogues and Other Memories Cancel reply