- Introduction

- How Slaves were Employed

- Agricultural Slavery

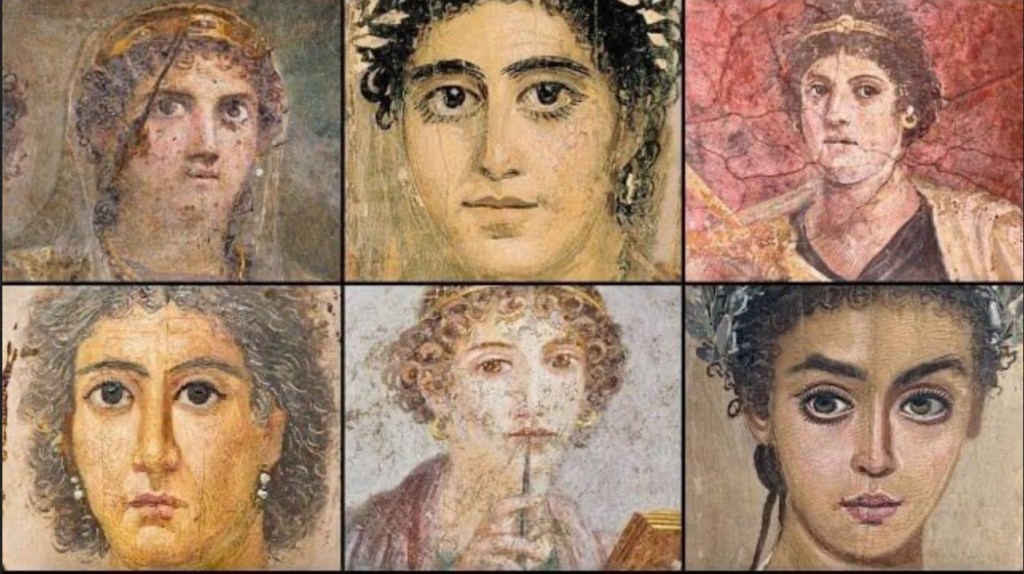

- Familia Urbana – Household Slaves

- Sexual Exploitation

- Footnotes

- Other Sources and Further Reading

Introduction

Conversations about slavery often focus on the trans-Atlantic slave trade which shipped, in horrific and inhuman conditions, at least eleven million Africans from their homelands to the Americas. This focus on the “Middle Passage” is unsurprising given the trade’s long-term consequences on both side of the Atlantic and it was without doubt a significant episode of human cruelty that lasted at least 250 years.

However, if it is viewed in isolation or labelled, as it often is, as The Slave Trade, we remove it from its African context and misrepresent its place in the global history of slavery.

In a series of essays I have explored slavery in its different forms across the ages highlighting the self evident truth that humans have been enslaving each other for thousands of years; probably ever since the Neolithic period when humans began to farm and form semi-permanent or permanent settlements. There is a strong relationship between slavery and farming but even some hunter-gatherer societies have practiced slavery.

It could be argued that the most surprising event in the history of slavery was the rise in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of popular movements to protest against and abolish the trade in humans.

How Slaves were Employed

Roman slaves can be divided into two large groups: servi privati, slaves owned by private citizens who made up the majority of the slave population and servi publici, slaves owned by the state.

State slaves undertook a wide range of roles that, today, we might consider the function of the civil service or municipal council workers. Some were servants to men in public office, many held administrative posts in the palace and the roles of magistrates’ lictors, jailers and executioners were usually assigned to slaves. It has been argued that by the 2nd Century AD twenty percent of people holding municipal office were either slaves or freedmen. 1

In 22 BC the aedile Marcus Egnatius Rufus set up a rudimentatry fire service but the Emperor Augustus saw this as an overtly political act to undermine his authority so he asigned 600 of his own slaves as fire fighters. 2

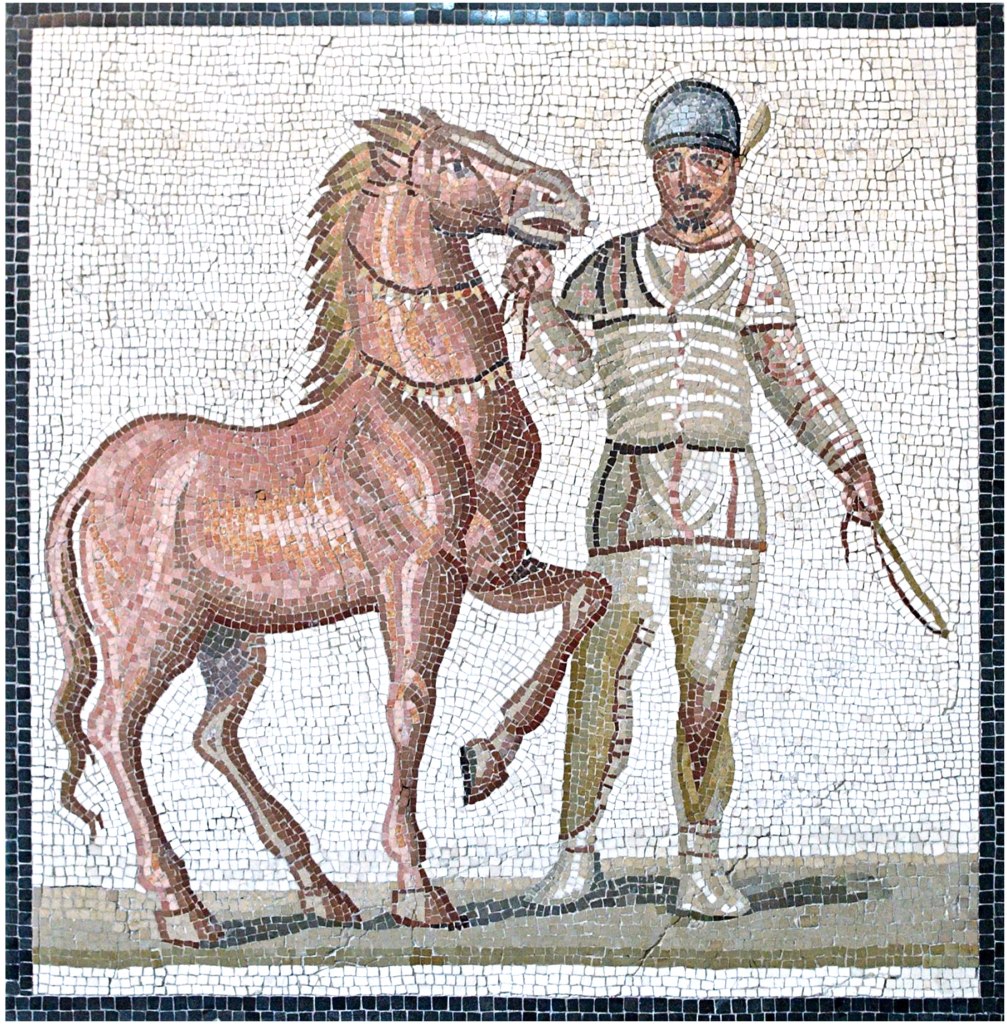

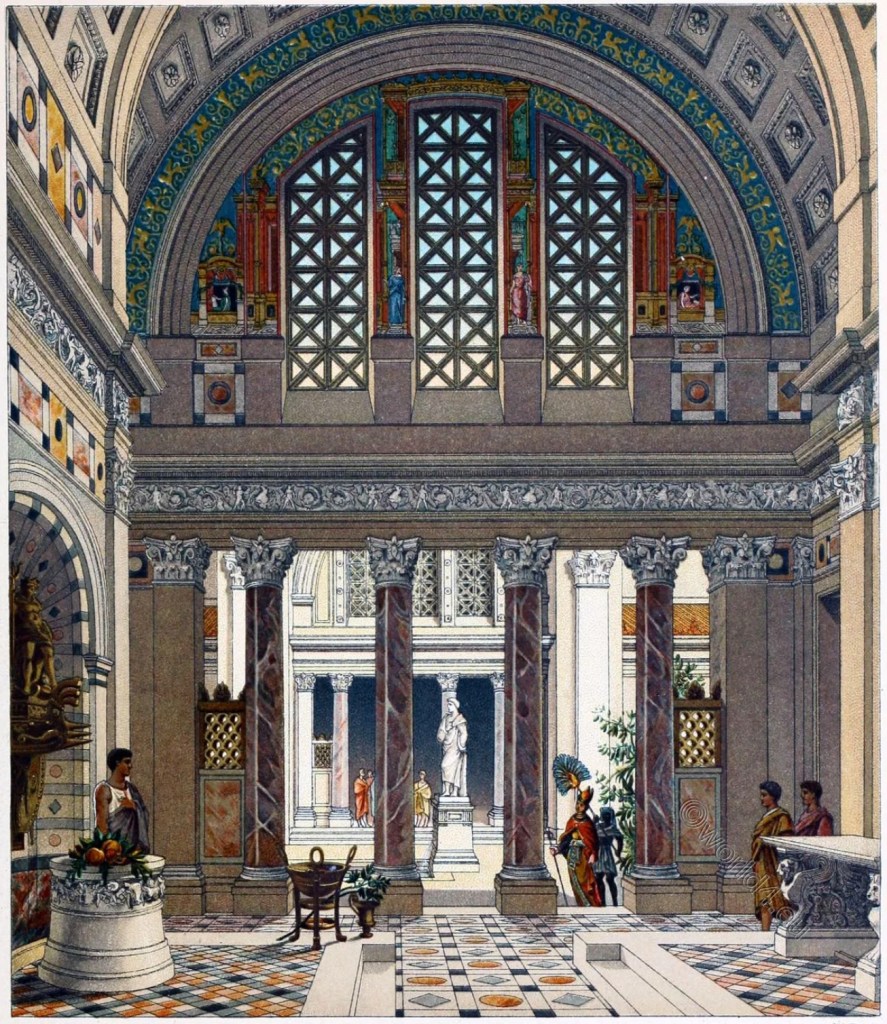

After a serious fire in AD 7 Augustus set up the cohortes vigileum or vigiles (see left) with 6,000 men who were mostly latini luniani, ex-slaves who had been freed illegally.

A Roman citizen of limited means would own a small number of slaves; some would work in their home as domestic servants and some would help work their owner’s land. These were slaves as tools or beasts of burden similar in function and status as a washing machine or a rotavator.

At the other end of the scale elite Romans owned large numbers of slaves but their roles were far more complex; some were still domestic staff although often fulfilling roles that were unnecessary in a lower status household such as hairdressers, masseurs or cup-bearers. Many would have been working on the land but food production on the Italian peninsular was often more about feeding the owner’s family and staff than for commercial ends.

But there are then two categories of servi privati, privately owned slaves, that typically only apply to elite citizens and wealthy freedmen; firstly, slaves as an economic asset, owned specially for the purpose of making money for their owner working in viniculture, mining, trade, industry, a bakery or a bathhouse or any of the myriad of commercial enterprises that serviced Roman society.

The last group are slaves owned as a conceit, ownership to show society the wealth and status of the owner or to caress the owner’s ego. Bradley argues that this form of ownership :

“…. stresses the slave’s subjection and suggests that slavery should be understood principally as a social relationship founded on the exercise of authority over an inferior party by a superior party.” 4

The Roman equivalent of driving a Bugatti or wearing a Patek Philippe watch was to enter the forum with a retinue of 50 slaves in tow arrayed in a military formation. Ammianus Marcellinus wrote:

“Some (men) are magnificent in silken robes, ….. and are followed by a vast troop of servants, with a din like that of a company of soldiers. Such men when, while followed by fifty slaves apiece, they have entered the baths, cry out with threatening voice, “Where are my people?””5

It is infeasible to describe slavery in every sector of Roman society and the Roman economy; because, without exaggeration, slaves at some point in Rome’s first millennium were in every walk of life other than holding public office.

Some writers suggest that slaves could not serve in the army, as it was a role reserved by law for citizens, but rules were there to be broken and when recruitment failed to fill the legions after heavy loses during the Punic Wars in 215 BC the state purchased 8,000 slaves plus 6,000 debtors and convicts, volones, to fill the ranks. 6

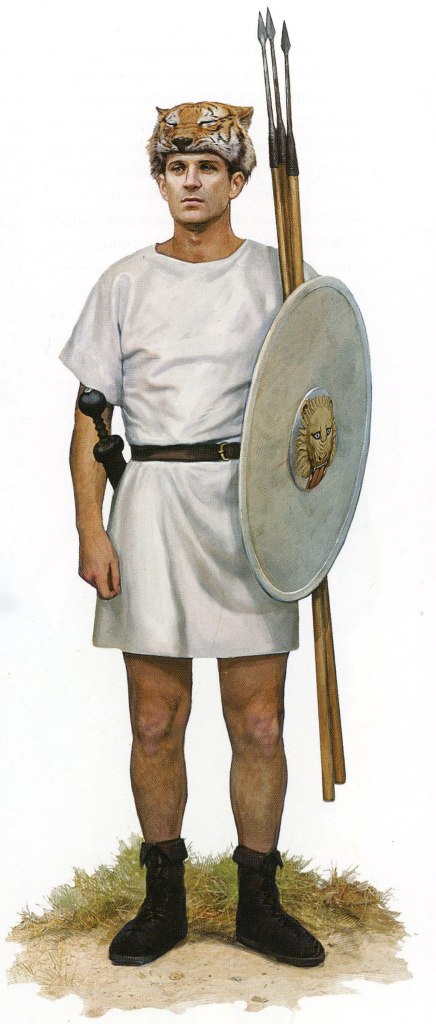

Right: Light infantryman from around 220 BC 7

In this article I will initially look at farming and its relationship with slavery in some detail for two reasons: firstly because there were more slaves engaged in agriculture than in any other sector and probably more than in all the other sectors combined. If this assumption is correct more than 5 million slaves were working on the land across the empire in the time of the first emperor Augustus. Secondly, because farming not only underpinned the Roman economy and fed a huge urban population it was fundamental to how the Roman’s saw themselves as citizens, farmers and soldiers.

The second and best documented group of slaves I will consider are the Familia Urbana, the men and women kept in the wealthy Roman’s city residence who not only serviced his and his family’s every need but displayed his status.

And, finally, there is a much repeated cliche that prostitution is the world’s oldest profession, an idea that has little or no basis in fact; a more valid argument might be that sex slavery and sexual exploitation is one of the oldest and most consistently pursued forms of slavery and one that is still prevalent in modern societies across the globe. Because of this long history sexual exploitation is the third area of slave employment covered here.

Agricultural Slavery

Farming and the Roman Ideal

Rome’s economy was always based on farming. The most traded goods in the Rome were consistently grain, olive oil, wine and salt and at different times they went to war to increase their access to salt and grain. It is therefore not surprising that, from early in the days of the Republic and throughout the Imperial Age, the largest single group of slaves were agricultural workers and those employed in trades associated with food production.

Rome had been founded by farmers and for the next millennium Romans saw the characteristics of a good farmer as the requisite qualities of a good Roman: diligence, determination, austerity, gravity, discipline and self-sufficiency. 9 They created a myth of national character that reflected these virtues and a creation myth that described the rugged farmer leaving his plough to defend Rome from the barbarians before returning to his team of oxen.

In 458 BC a Roman army was surrounded by the Aequi, a tribe from central Italy, on Mount Algidus, 50 km southeast of Rome. The senate voted to appoint Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who had been consul in 460 BC, as dictator.

Pliny the Elder picks up the story:

“Cincinnatus was ploughing his four jugera of land upon the Vaticanian Hill – the same that are still known as the Quintian Meadows, when the messenger brought him the dictatorship – finding him, the tradition says, stripped to the work, and his very face begrimed with dust. “Put on your clothes,” said he, “that I may deliver to you the mandates of the senate and people of Rome.” ” 10

[Right: Statue of Cincinnatus found at Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli]11

Cincinnatus left his plough, raised an army and defeated the Aequi in 15 days before relinquishing his dictatorship and returning to his farm.

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, best remembered as Scipio, defeated Hannibal and the Carthaginians in the Second Punic War in 201 BC to become one of Rome’s great heroic generals. Seneca the Younger visited Scipios’s villa around 250 years after his death and wrote to a friend describing the surprisingly small and dark bathhouse:

“In this little nook , the terror of Carthage ….. washed a body which had been exhausted by farm work. For Scipio kept himself busy with hard labouring even ploughed the land himself, as, of course, was the custom of our ancestors.” 13

The ideal Roman, as exemplified by Cincinnatus and Scipio, was a citizen, a farmer and a soldier and the classical writers looked back to the golden age when the elite farmed their own land, the pinnacle of what modern historians call, Romanitas, the spirit of being Roman that encompassed their cultural, political and social outlook.

Yet, soon after the Punic Wars, and probably earlier the self-sufficient farmer tending his own land with help from his family had all but disappeared. The Roman countryside, campagna di Roma, was owned by a small number of elite citizen landlords and the farmers were either freeborn tenants or slaves and eventually, probably quite quickly, the majority of slaves owned by elite Romans were working in agriculture.

Some historians suggest this change happened due to citizen soldiers leaving their farms to fight the Punic wars and perhaps this was a factor but Tenney Frank, 15 as discussed in the next section, puts forward a different argument, he believes that changes in the very soil and microclimate of the Latium Plain and erosion on the hills caused a serious decline in subsistence-level, arable farming and that small farms were replaced by large livestock farms, viniculture and olive groves that were mostly owned by a comparatively small number of elite citizens. 16

The story of Cincinnatus highlights the great contradiction of Romanitas; after the Punic Wars the elite Roman, the citizen, farmer and soldier whose class owned the majority of the land lived in Rome, perhaps visiting one of his farms for holidays, but certainly never to be found sweating behind the plough:

Right: Tiberius in the formal dress of an elite citizen. 17

Pliny ends his story with:

“But at the present day these same lands are tilled by slaves whose legs are in chains, by the hands of malefactors and men with a branded face!” 18

The Evolution of the Campagna di Roma

Rome was founded in the hills of Latium, now Lazio, between the River Tiber and Mount Circeo 100 km to the south and the Appenine Mountains to the east. The campagna di Roma, the countryside south and east of Rome, was a narrow strip of land with soils that had been created by comparatively recent volcanic activity. This soil was initially rich in nutrients and fed with springs and rivers that originated on the forested slopes of the Sabine Hills, the Volscian range and the Appenines.

Around 1000 BC these lands were settled by people from, what is now, northern Italy and they farmed here on the rich but shallow soils kept warm and humid by the surrounding forests and irrigated by the complex web of drains, tunnels and dams they constructed.

©Steve Middlehurst

As time went on these early farmers had to fight a battle against the elements, the soil was thin and as they stripped the turf and uprooted the trees it became vulnerable to erosion. As the hills were deforested the microclimate became drier and springs that had once delivered water all year round started to dry up, first in summer and eventually all year. The soil washed down from the deforested hills turned the Sabine hills into bare rock, choked the waterways in the valleys and created marshland where crops had once grown.

Rome’s conquest of the tribes to their north and east allowed farmers to switch from arable to pastoral farming, seeding their fields as pasture and herding cattle, sheep and goats. In the long dry summers they could take their herds and flocks to the high mountain pastures that had been the territory of the Sabines and Aequians bringing them back down in winter to fatten on the rich pastures of what were once thriving arable farms in the lowlands.

However, this type of farming pushes out the small holder or subsistence farmer and lends itself to land owners who can finance large herds or flocks, own sufficient tracts of winter grazing and have herders to tend the animals for half the year high in the Appenines and half in the lowlands.

This fundamentally changed the demographics of the region, a 1,000 hectares of the plain could previously support more than 200 subsistence farming families but was now home to a small number of enslaved herdsman and shepherds with their masters’ animals.

©Steve Middlehurst

Wool was a valuable commodity so as the subsistence farming families left the elite citizens moved in with access to the capital needed to build up their flocks and to increase their ownership of the land required for winter pastures. The number of land owners, who by now were based in towns and cities, mostly in Rome, shrunk as the size of their holdings grew. By the 3rd century AD large estates, latifundia, had replaced small farms across all of Italy and most of the provinces

As arable farming declined on the Latium plains viniculture and olive farming developed on the denuded and steep slopes of the Alban hills where it thrives to this day.

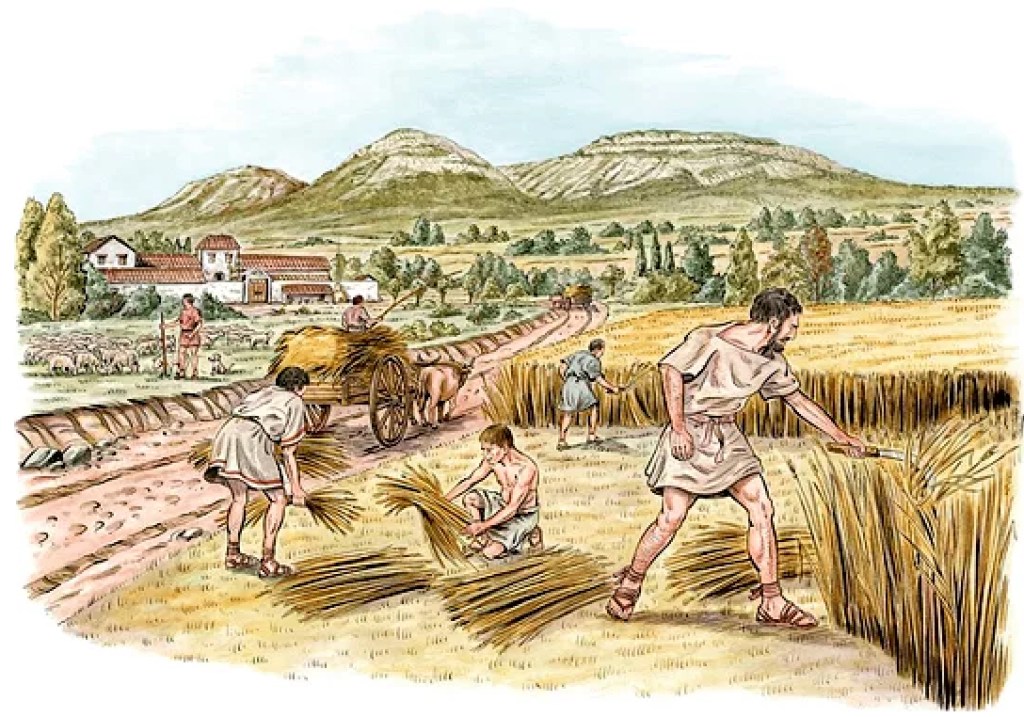

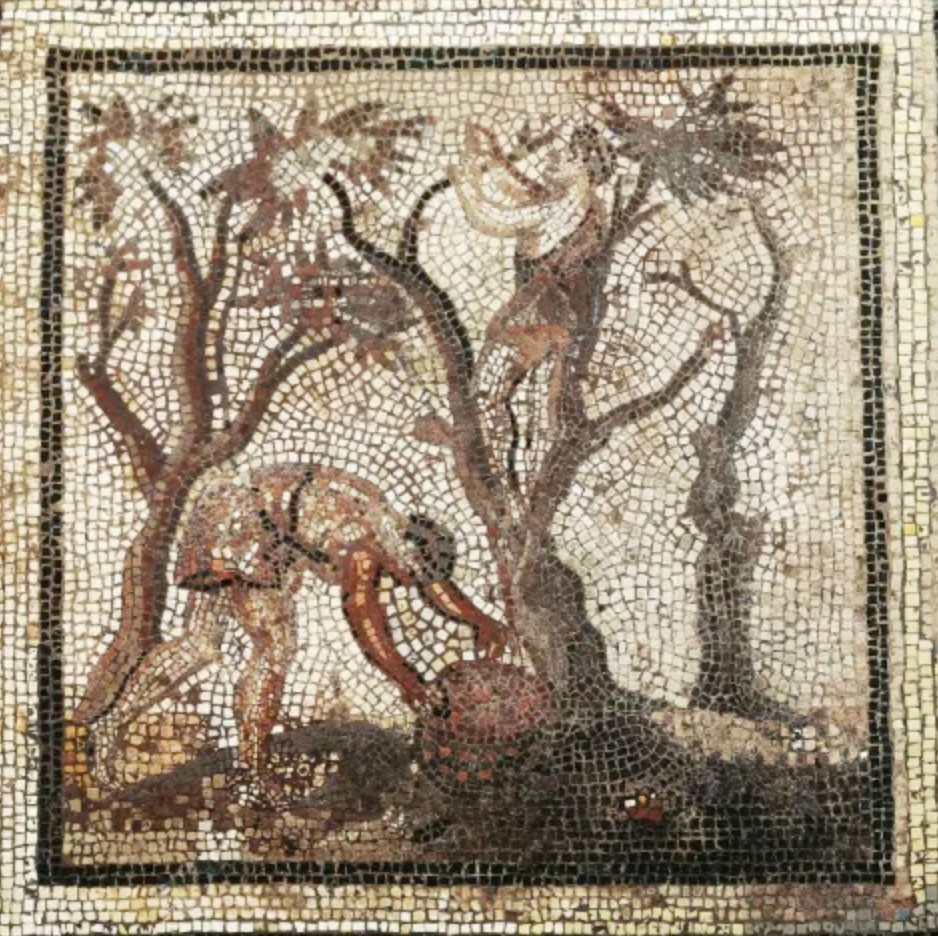

Right: Slaves picking grapes

Vineyards and olive groves need scale to be viable and whilst wine and olive oil become valuable cash crops olive trees need ten to twenty years before they produce a viable crop and vines take four years to reach full yield.

They are an obvious investment for a wealthy landowner who can afford the manpower to plant and tend unproductive plants for many years and who can invest in presses, amphorae, barrels, warehouses and transport before receiving any income.

Right: Slaves pressing olives

Rome expanded across the Italian peninsular as arable farming on the Latium Plain became increasingly difficult and this stimulated an estimated 60,000 Latin colonists to spread out across Italy in the eighty years leading up to 264 BC 20 acquiring new farms.

Despite the loss of arable land in her immediate hinterland by expanding her territories Rome continued as an agricultural economy and Romans remained farmers and the elite increasingly became real estate capitalists.

However, except in a few localised valleys where the soil remained fertile and irrigation was possible and where citizen small holders could still survive the farms on the Latium Plain and beyond grew large, owned by absent landlords and primarily farmed by slaves.

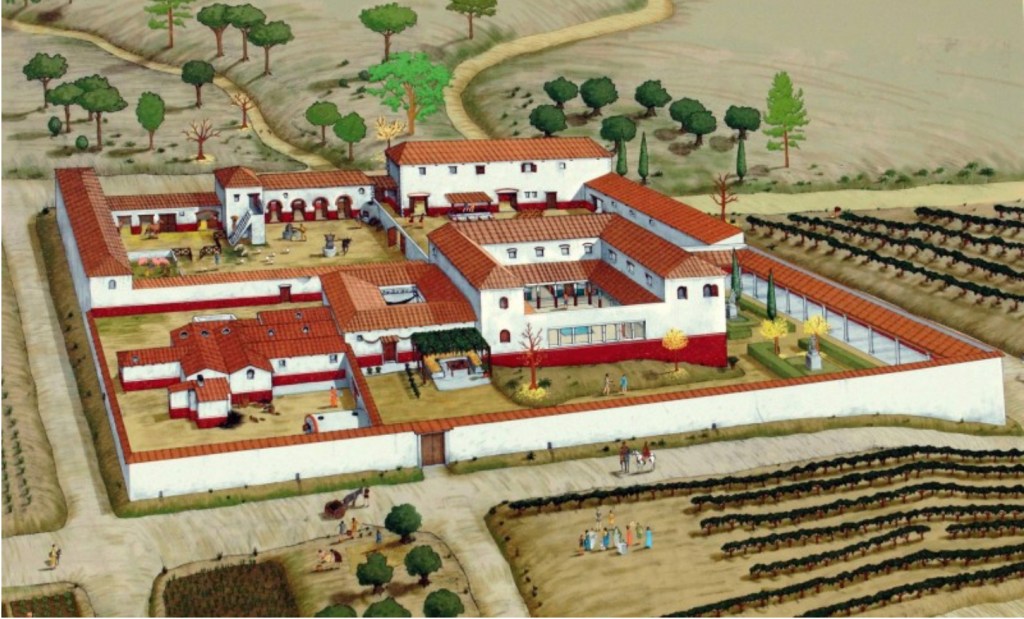

The farms, which are better described as farming estates, evolved into two types; the country seat of an elite Roman, the Downton Abbeys or Blenheim Palaces of ancient Rome, and the agro-industrial farm run solely for profit.

The country seats needed to be close to the City where the owner conducted his political and commercial life and are described by Harold Johnston:

“They were maintained upon the most extravagant scale. There were villas and pleasure grounds, parks, game preserves, fish ponds and artificial lakes, everything that ministered to open air luxury.

Great numbers of slaves were required to keep these places in order, and many of them were slaves of the highest class: landscape gardeners, experts in the culture of fruits and flowers, experts even in the breeding and keeping of the birds, game, and fish, of which the Romans were inordinately fond. These had under them assistants and laborers of every sort, and all were subject to the authority of a superintendent or steward (vīlicus), who had been put in charge of the estate by the master.” 22

The Importance of Food Production

Cura Annonae – The Corn Dole

Rome’s economy was underpinned by agriculture but perhaps even more importantly the social stability of large cities depended on an uninterrupted supply of grain, olive oil, and wine at affordable prices. Bread and a kind of porridge made from millet or wheat, puls or pulmentum, were the staple diet of the Roman poor.

Gaius Gracchus, a tribune of the people in 123 and 122 BC, was the first official to address the issue of affordable grain for poor Roman citizens. Grain was often ground and boiled as a porridge, puls or pulmentum, or, if an oven was available made into bread. Gracchus was concerned that the price of grain fluctuated through the year making it unaffordable at times. He introduced a law whereby the state sold a monthly ration of grain to citizens at a fixed price.

Sulla temporarily suspended the fixed price distribution of grain in 90 BC but it was reintroduced in 78. In 58 BC Publius Clodius Pulcher went further and introduced legislation that entitled male citizens to a monthly ration of grain free of charge, the Cura Annonae or dole. Following the rules of unexpected consequences this stimulated a surge in Rome’s urban population as peasants from the countryside came into the city while many owners freed some of their slaves to make them eligible for the dole.

By Julius Caesar’s time it is estimated that 320,000 people living in Rome were receiving the dole, a number that he cut in half by implementing more diligent checks on claimants’ citizenship. However, the beneficiaries rose back to 320,000, or a third of the city’s population, under Augustus before being controlled back down to around 200,000 which is where it stayed. The system later spread to other cities including Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch.

Throughout the Republic and the Imperial Age there continued to be a thriving free market for grain to meet the demands of people ineligible for the dole which included women, children, slaves, government officials and non-citizens.

Clearly food production in any society is important but the creation of the Cura Annonae made a significant proportion of Rome’s population dependant on the state. It is estimated that Rome needed over 250,000 tonnes of wheat a year to feed the city so maintaining a consistent supply of grain despite poor harvests, pirates in the mediterranean, ships lost at sea and the sticky fingers of corrupt officials was a major priority of the Republican state and then the Emperors.

The Risk of Social Unrest and Food Riots

There were several occasions when the grain supply failed or rumours spread that it would fail or allegations arose that the elite were profiteering by holding back stocks of grain. The result was often public unrest and rioting. Tacitus reports one such occasion:

A shortage of corn again, and the famine which resulted, were construed as a supernatural warning. Nor were the complaints always whispered. Claudius, sitting in judgement, was surrounded by a wildly clamorous mob, and, driven into the farthest corner of the Forum, was there subjected to violent pressure, until, with the help of a body of troops, he forced a way through the hostile throng.

It was established that the capital had provisions for fifteen days, no more; and the crisis was relieved only by the especial grace of the gods and the mildness of the winter.

And yet, Heaven knows, in the past, Italy exported supplies for the legions into remote provinces; nor is sterility the trouble now, but we cultivate Africa and Egypt by preference, and the life of the Roman nation has been staked upon cargo-boats and accidents. 27

Tiberius, who succeeded Augustus, wrote to the Senate in AD 22 to remind them of the fundamentals importance of the Cura Annonae:

‘This duty, senators, devolved upon the Emperor; if it is neglected, the utter ruin of the state will follow.” 29

Tiberius knew that failure to secure enough grain to feed Rome’s poor would lead to nothing less than a total collapse of the state and Tacitus quite rightly recognised that Rome’s existence was being gambled on cargo boats and the accidents that might befall them but he fails to mention that the Rome was also utterly dependant upon the millions of slaves who produced the grain in Egypt, North Africa, Sicily and Sardinia.

The perfect Roman: citizen, farmer, soldier had been replaced by a land owning aristocracy who had delegated the stability of the state to slaves and estate managers working the land in distant provinces.

Baking Bread and Slavery

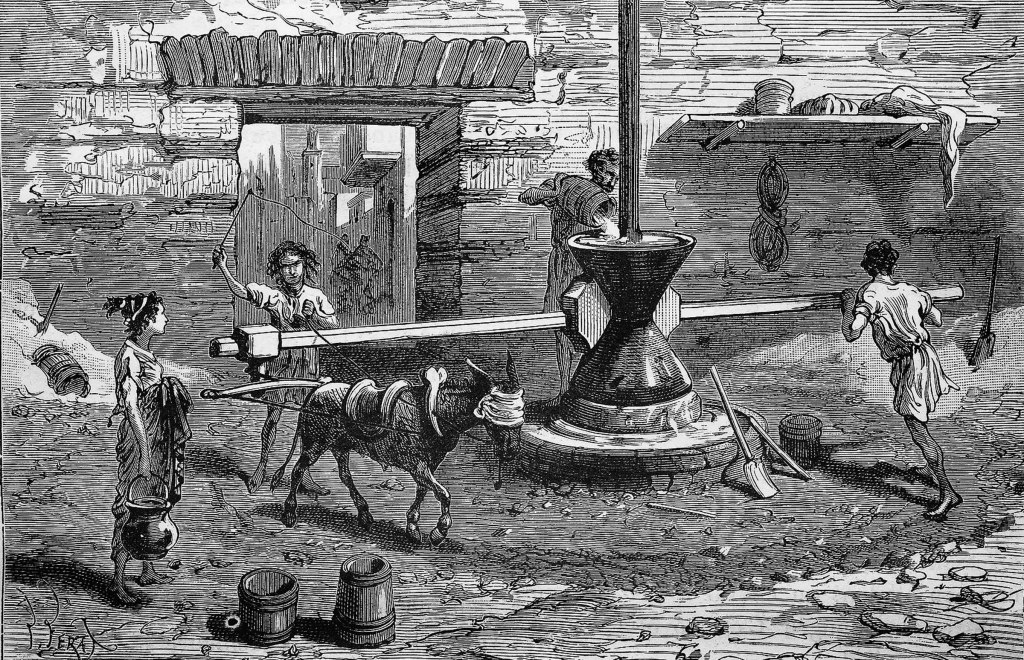

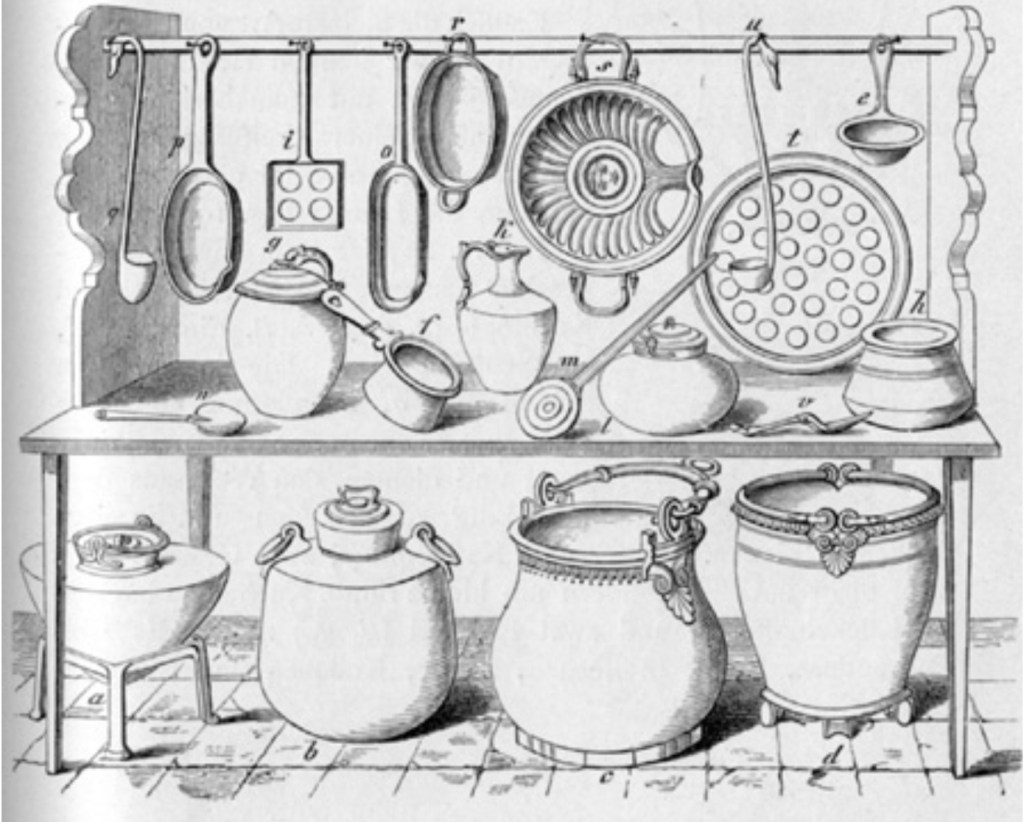

Four millstones that would have been operated by a donkey and a slave working at either ends of a wooden bar are on the right and an oven to the left. The original bakery would have been enclosed inside a building. 30

Grain was grown in far away provinces and shipped to Italy but bread was obviously a localised industry. When Romans still lived on their farms Bread was baked at home or in communal, village ovens but as they became urbanised only the wealthiest households had a viable location for a bread oven. The average Roman living in cramped rooms in Rome’s tenement blocks or on the top floors of Pompeii’s shops had no cooking facilities which explains the proliferation of fast food stalls excavated in Pompeii and the discovery of around 35 bakeries in the town.

Recent excavations in Region IX, insula 10, a previously untouched part of Pompeii, has revealed a large private residence probably owned by Aulus Rustius Verus, a local politician and business man.

The ground floor of the house includes the largest private bath complex found in the town, a dining room large enough to host banquets, other reception rooms, store rooms and a porticoed garden. The main rooms are decorated with exquisite frescoes and mosaics underlining the wealth of the owner.

However, the building reveals the dark secret of the Roman elite’s disproportionate wealth. In front of the house two of Aulus Rustius Verus’ business ventures have been found; one is a laundry and the other a bakery.

The bakery is cramped with small, barred windows set high in the walls that would have let in little natural light and a single entrance leading to the atrium of the private house; inside there are four hour-glass millstones similar to those shown above, one is inscribed with the letters “ARV” showing the businesses and house probably have the same owner.

The four millstones were linked with a clockwork-like mechanism and were operated by a blindfolded donkey and a slave working in unison. The donkey was kept in a small stall off the grinding area. There was a large wood fired oven, like a modern pizza oven, and an area to make and kneed dough.

It would have been dark, incredibly hot, humid and stinking of human and animal sweat, urine and excrement. It is more than likely that the slaves who worked here were permanently restrained, sleeping on empty sacks on the floor.

The Pompeii excavation team described the space as a “prison bakery”. 33

Roman Writers on Farming

Between the middle of the 2nd century BC and the 1st century AD at least five Roman writers documented their thoughts on Agriculture: Cato the Elder (234 to 149 BC), Varro (116 to 27 BC), Virgil (70 to 19 BC), Columella (AD 4 to 70) and Pliny the Elder (AD 23 to 79).

Other than Virgil, who was born of peasant stock and who wrote poems that romanticised farming and the rural life, these writers were elite Romans of equestrian or senatorial rank and are unlikely to have ever got the soil of the campagna di Roma, or anywhere else, under their finger nails. However, as intellectual and well read owners of farms, their views and guidance on farming probably reflects the methods and attitudes of their times.

The earliest surviving complete work of latin prose is Cato the Elder’s De Agri Cultura, “On Farming”, which he wrote in around 160 BC. It is a remarkable document that delves deeply into farming practices giving, for example, infinitely detailed lists of the equipment needed in each part of the farm right down to how many keys were needed for the pressing room door.

For a 100 jugera (25 hectares) vineyard he specifies the number of workers needed:

“An overseer, a housekeeper, 10 labourers, 1 teamster, 1 muleteer, 1 willow-worker, 1 swineherd — a total of 16 persons;”

When Marcus Terentius Varro commented on this passage around 100 years later he is quite certain that they are all slaves. That was probably the correct interpretation; Cato probably assumed the reader knews that most agricultural staff were slaves as, when he described the need for two watchmen to sleep in the pressroom, he specified they must be freemen.

When Varro wrote De Re Rustica, his treatise on agriculture in the first century BC he explained that the land was worked by the interaction of three elements, the;

“……. articulate, the inarticulate, and the mute; the articulate comprising the slaves, the inarticulate comprising the cattle, and the mute comprising the vehicles. All agriculture is carried on by men — slaves, or freemen, or both;”

He advises the land-owner to manage their slaves with a foreman who is older, more knowledgeable and can read and write. He will also be a slave but is rewarded with a peculium 37and:

“mates from among their fellow-slaves to bear them children; for by this means they are made more steady and more attached to the place.”

Of course allowing a foreman slave to sire children was also to the master’s advantage as the chilren would be born as vernae, home-born slaves.

Lucius Iunius Moderatus Columella, published his 12 books of De Re Rustica, the most comprehensive of the Roman treatises on agriculture, in the AD 60s.

Left: The olive harvest

Columella was born in Spain near the modern city of Cadiz and served as a military tribune suggesting he came from the upper ranks of Roman society like Cato, Varro and Pliny. He shows little trust of his slaves advising prospective owners not to buy farms in remote provinces as they needed to be seen to visit their farms on a regular basis, otherwise:

“…… it is certain that slaves are corrupted by reason of the great remoteness of their masters and, being once corrupted and in expectation of others to take their places after the shameful acts which they have committed, they are more intent on pillage than on farming.” 38

He expands on this theme saying that without supervision by either owner or a free farmer:

…….. slaves do it (the land) tremendous damage: they let out oxen for hire, and keep them and other animals poorly fed; they do not plough the ground carefully, and they charge up the sowing of far more seed than they have actually sown; what they have committed to the earth they do not so foster that it will make the proper growth; and when they have brought it to the threshing floor, every day during the threshing they lessen the amount either by trickery or by carelessness. For they themselves steal it and do not guard it against the thieving of others, and even when it is stored away they do not enter it honestly in their accounts. 39

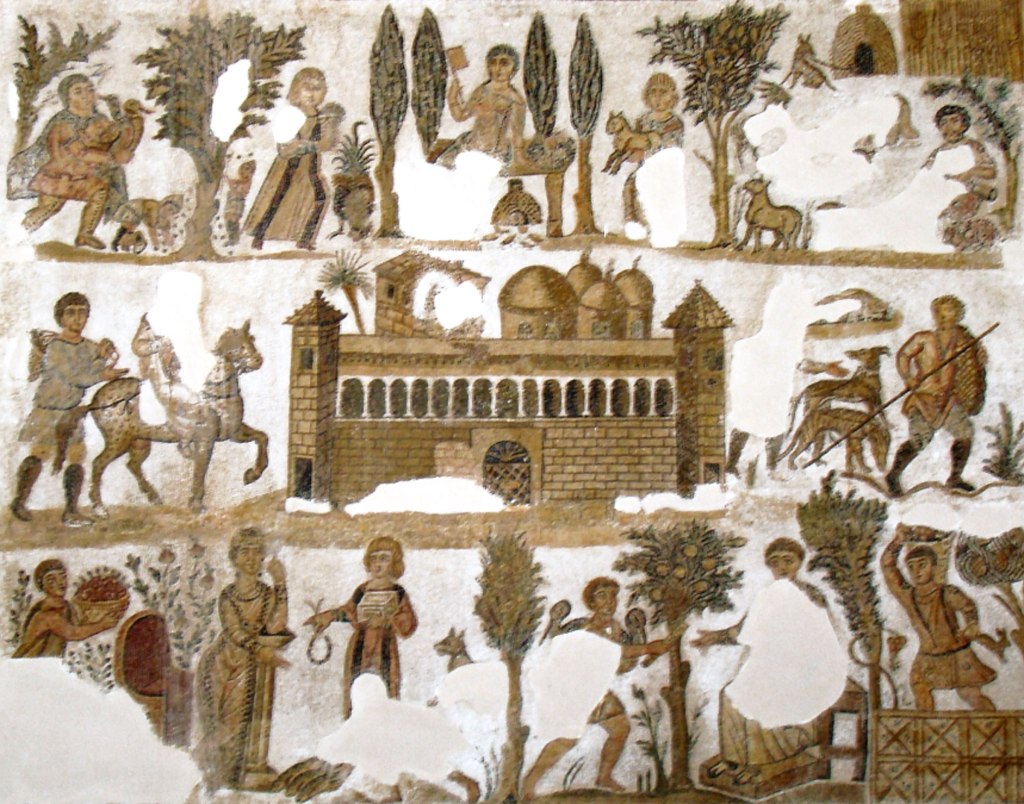

The villa of Los Cantos in southeast Spain. 40

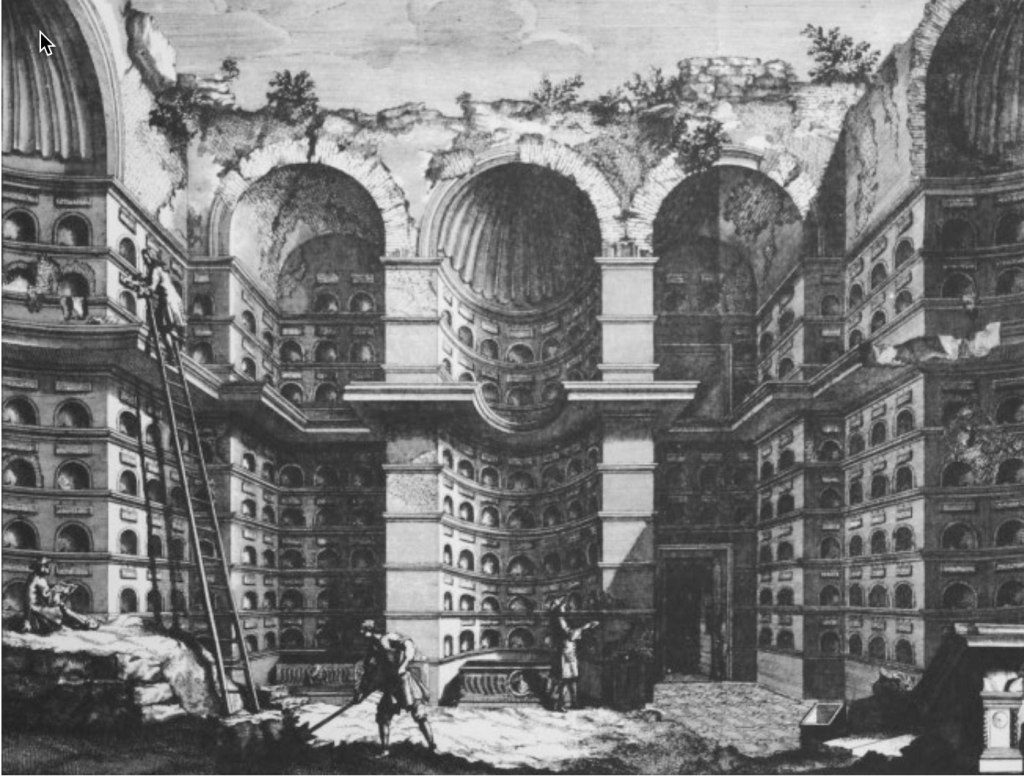

Columella describes the farm slave quarters as cubicles in the kitchen but he also advises how to design the slave prison or ergastulum or carcer rusticus:

…… there will be placed a spacious and high kitchen, that the rafters may be free from the danger of fire, and that it may offer a convenient stopping place for the slave household at every season of the year.

It will be best that cubicles for unfettered slaves be built to admit the midday sun at the equinox;

……. for those who are in chains there should be an underground prison, as wholesome as possible, receiving light through a number of narrow windows built so high from the ground that they cannot be reached with the hand.” 41

The lengthly passages on how to manage slaves in De Re Rustica describes the owner-slave relationship in stark terms. His basic assumption is that slaves cannot be trusted; they must work in small teams to limit the risk of revolt, be supervised in every task because not only will they steal from the owner but they will skimp rather than complete tasks diligently.

We are left with a dark picture of vast numbers of slaves, the majority of all the Romans’ slaves, toiling at the heavy labour of farming from dawn till dusk with their supervisors breathing down their necks constantly assuming the slave will fail in his or her duties or find a way to embezzle their master.

Some slaves are in chain gangs and sleeping overnight in dungeons; all are fed just enough, clothed just enough and cared for just enough to keep them productive. None of the writers mention manumission supporting the argument that it is unlikely that agricultural slaves could look forward to freedom.

Above: Slave shackles found on a body buried at Liverpool Street London. 42

To return to Cato, he advises that the owner of a farm needs a selling not a buying habit:

“Look over the live stock and hold a sale. Sell your oil, if the price is satisfactory, and sell the surplus of your wine and grain. Sell worn-out oxen, blemished cattle, blemished sheep, wool, hides, an old wagon, old tools, an old slave, a sickly slave, and whatever else is superfluous.”

If this advice was commonly followed the agricultural slave could not look forward to retiring on the farm where he or she might have worked for their whole life. When agricultural slaves become unproductive through age or sickness Cato and others advise their owners to sell them but who would buy an old or sick slave?

In the Republic a master could legally kill one of his slaves without reprisal but during the Imperial age owners’ rights were slowly restricted by a number of new laws.

One law stopped a master sending his slaves to the arena to fight wild beasts, another forbade an owner from just abandoning sick slaves, later he could be held responsible if he killed slave whilst inflicting punishment and a master was prohibited form killing a slave merely because they were old or infirm.

Eventually it became illegal for a master to kill a slave. However, Johnston points out:

“As a matter of fact these laws were very generally disregarded.” 43

These laws reveal what the classic writers never mention: sending worn out slaves to the arena, abandoning old or infirm slaves, killing them whilst inflicting punishment or simply just killing slaves when they became too old to work must have been happening often enough to warrant legislation.

When you read Roman slaves were generally treated well and often manumitted, so their system was more compassionate than ancient Greece or the antebellum Southern States of America or the Caribbean plantations recall that at least half of all Roman slaves, potentially 5 million men, women and children, worked on the land, most were never seen by their masters and very few were set free by anything other than death.

Familia Urbana – Household Slaves

A second large group of slaves were people who worked in the homes of wealthy Romans. The work of these slaves was dependant on the wealth and interests of their owners and, to some degree, on fashion. It is interesting to look at a few households where we know something of how they were organised.

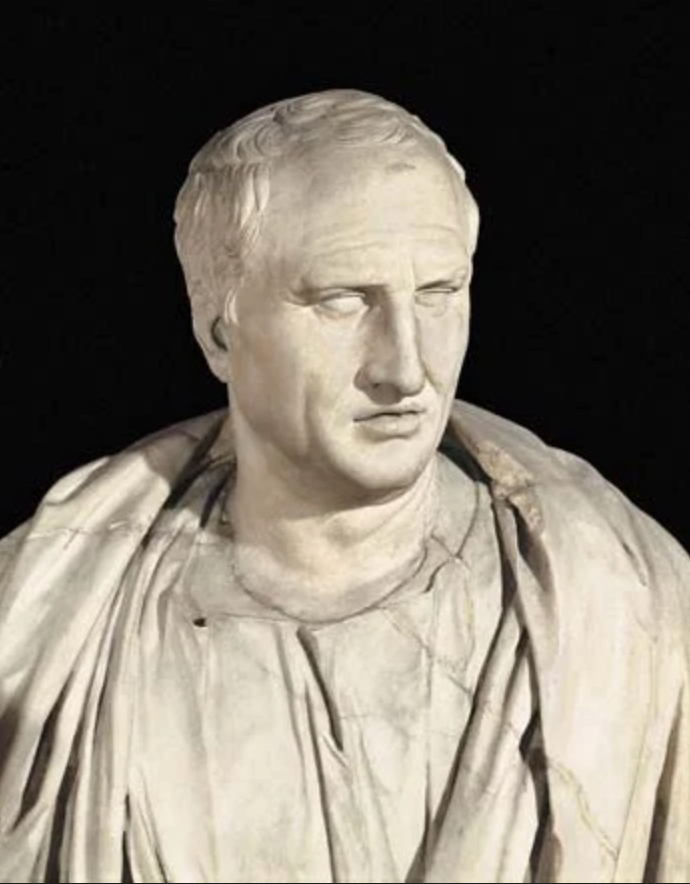

Cicero’s Household

Marcus Tullius Cicero (left 45) was an intellectual, a statesman, famous orator and luckily for us a prolific letter writer who lived during the time of the late Republic 106 to 43 BC.

Cicero was moderately wealthy, he owned around twenty properties including working farms and probably owned in the region of 200 slaves. 46

His familia urbana, or city household, was comparatively small by the standard of his times, perhaps 20 slaves and freedmen, but his staff reflected his interests and role as a senator and litigator.

Unusually for a Roman household we not only know his slaves’ functions we also know some of their names. 47 Whenever there is a chance to give any level of identity to a slave it is worth taking:

- His pedibus (personal attendant or footman) was Pollex who was trusted with other tasks suggesting he was more like an aide de camp.

- Philitimus, his dispensator (steward), paid tradesmen and suppliers and unusually was also the treasurer for all of Cicero’s other properties.

- Philitimus also supervised the household accounts which were kept by Hilarus and Eros who were actuarii (bookkeepers or accountants).

- Tiro was his ad manum (private secretary); he was valued highly and freed in around 53 BC. It is possible that Tiro was verna, a slave born in Cicero’s family’s household; he was clearly educated and trusted enough to be lent to Cicero’s brother in 54 BC to write political reports.

- Spintharus was a secretary;

- Aristocritus, Dexippus, Hermia, Mario, Aegypta, Phaetho and Menander were tabellarii (messenger boys or letter carriers);

- Dionysius and Sositheus were lectores (readers) who would read documents or books out loud to Cicero

- There were also a number of librarii (clerks or copyists) of whom we only know of Chrysippus who deserted Cicero’s sons when travelling abroad.

The reader Sositheus died young and Cicero wrote:

“My reader Sositheus has died. He was a genial youth, and his death has affected me more than a slave’s death seemingly should.” 48

It was not all plain sailing in Cicero’s household, Dionysius, another reader was stealing books from his master’s library but escaped before he could be taken to task which must have been particularly upsetting because he had tutored his son Marcus. At one point Cicero eagerly anticipated Dionysus’ return to Rome not just to continue Marcus’ eduction but because he also benefited intellectually from his presence 50 and he had previously accompanied Cicero on a trip to Tusculum:

“I have taken nobody away with me except Dionyius, but I am not afraid of running short of conversation in such delightful company.” 51

Cicero also mentions a groom, litter bearers, a cook and a manservant as well as a a hall porter who ushered in guests and kept the atrium clean but we have no names for these men. His wife must have had maids and slaves who could weave or sew.

Cicero freed a number of his slaves and had correspondence with his wife regarding her desire to free some of hers but spartacus

Livia’s Household

Cicero was wealthy enough to own several properties and perhaps 200 slaves but he was not among the richest Romans. They owned estates rather than farms and, in the city, mansions rather than houses. The number of slaves in their familia urbana was so great they were divided into decuriae, groups of ten, each with its own supervisor and organised by function. There might be a decuria running the kitchen, another for the dining room, one for the bedrooms and so forth. 52

Livia Drusilla was Augustus’ wife and mother id the emperor Tiberius, e know so much about her household because a columbarium, a building where funerary urns were stored in niches, known as theMonumentum Liviae, was excavated in 1726. It is recorded as having over 550 niches many containing two urns with marble plaques recording the occupants. The columbarium was run by a consortium of freemen and slaves but Livia’s slaves, freedmen, their relatives and descendants appear to be the largest group interned there. 54

Based on the known inscriptions it appears that Livia, had 79 household staff employed in 46 different roles in Augustus’ palace on the Palatine in Rome; about half were slaves and half freedmen or freedwomen and surprisingly the majority were men.

Running her household she had two dispensatores, (stewards) who probably reported to a procurator castrensis, which is a military title meaning camp manager and applicable in the imperial household because the emperor’s residence was often referred to as his castra or camp. This man who would nearly certainly have been a freedman with overall responsibility for Livia’s financial affairs and her household.

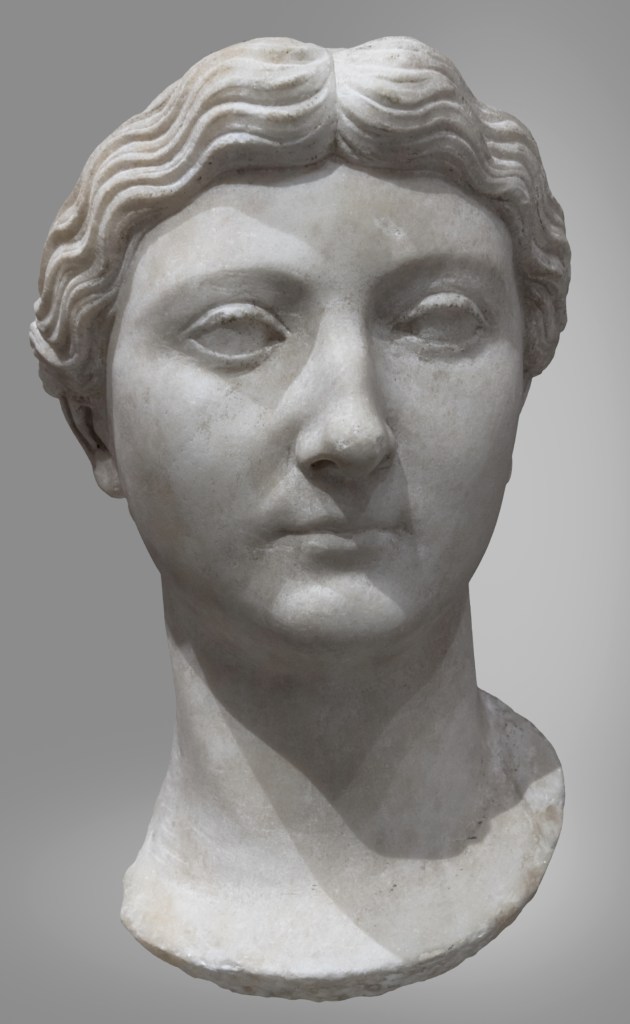

Left: Livia Drusilla 55

Other staff included: 57

- An accounts team of actuarii (accountants) and tabularii (record keepers);

- A servus ad possessiones: a slave who was perhaps specifically concerned with protecting her portfolio of property and other possessions.

- A custos rationis patrimoni: (guardian of the inheritance) who might have managed her inheritance from Augustus or perhaps been similar to a procurator patrimoni who administered the overseas estates of the emperors.

- Servus insularii: slaves who lived in her apartment blocks as concierges or agents and collected the rent from her tenants.

- There would have been a number of secretaries with some able to take dictation. This is a confusing area as Ad manum servus was a slave with secretarial duties, whilst ad manum servi were slaves kept to hand to undertake any business. 59

- There were a number of librarii (clerks or copyists).

- A mending woman called Lochias.

At the entrance to the house there was a Ostiarii, or doorkeeper, who kept out unwanted callers and checked on slaves who were leaving the premises.

A number of atriensis or slaves of the atrium ranged from a majordomo to the cleaning and maintenance staff who worked for him.

Above: the famous “Cave Canem” – beware of the dog mosaic at the entrance to the “house of the Tragic Poet” in Pompeii

- Diaetarchae: suite managers for specific rooms or apartments within the house.

- Tricliniarchae: dining room keepers.

- Ministratores: waiters.

- A Structor: a carver.

- Rogatores: who probably had the job of issuing invitations and asking visitors their business.

- A servus ab admissione: who decided whether and when visitors would be admitted to see Livia.

- A nomenclator: who reminded her of people’s names.

- A supra cubicularios: grand chamberlain who controlled who could enter the mistress’ bedroom suite and supervised the bedroom staff.

- Cubicularii: at least 6 chamberlains working for the supra cubicularios.

- An ornatrix: her hairdresser.

- Tonsores: who looked after the storage of clothes and cut her hair and nails.

- Ornatrices: dressers of whom she had a “large number” 60

- A veste or ab vestum: who was the mistress of her robes

- Vestipicae: assistants to the mistress of the robes who folded and put away clothes.

- Ab ornamentis sacerdotalibus: a freeman who selected the correct clothes and jewellery to be worn on formal occassions.

- Ab ornamentis: two slaves who looked after those ceremonial clothes.

- A capsarius: who possibly carried a small box when she went out as the equivalent of a handbag.

- A capsarius a purpuris: someone who looked after and put away her imperial purple robes.

- An unctrix: a professional masseuse of whom she had two.

- An ad unguenta: someone who looked after the perfumed oils used by the masseuse.

- Pedisequi and pedisequa: several footmen and their female equivalents would have followed Livia whenever she left the house and to run errands.

- A puer a pedibus: typically a slave boy who would have been at Livia’s side ready to run errands.

- Delicia: small children, often vernae (slaves born in her house), who Livia just enjoyed having around her. It is rumoiured that she liked them to be naked.

- An opsonator: the catering manager responsible for supplying the kitchen.

- A libraria cellaria: the stores clerk who presumably worked for the opsonator and maintained the kitchen store inventory.

- An archimagīrus: a chef or chief cook who would have been supported, in the kitchen, by many coqui, cooks, and pistores, bakers.

- There was a freedman who weighed out the wool for the lanipendus, the slave women who spun it.

- There were probably textores, weavers and vestificae, who made clothes and there were several sarcinatores who mended clothes.

- A calciator made her shoes.

- It appears that she had a whole medical team including doctors, a surgeon, an eye doctor, male and female medical orderlies who looked after any sick slaves and several midwives who, with a staff of this size, would have been kept busy with the next generation of slaves and the offspring of freedwomen in the household.

- There was a nutria, wet nurse, for her own children and possibly several others for the vernae, the children of slaves.

- There was a freedman paedagogus, a teacher for her children and later grandchildren and it is possible that she had another teacher for the slaves’ children.

- Structores, builders, maintained the structure of the house along with mensores, surveyors, marmorarii, marble workers and aquarii, plumbers. There were several other craftsmen, fabri, who were probably carpenters, smiths and general decorators.

- Her pictores, painters, created or touched up the frescos that decorate the Villa di Livia.

- She also had three freed and two slave aurifices, goldsmiths, and a argentarius, silversmith, as well as an inaurator, a gilder and a specialist in setting pearls but whilst they probably made jewellery for her they may have primarily been set up in a business or businesses that she profited from.

- A colorator polished wooden furniture and there appear to be specialist freedmen or slaves that look after prestigious furniture and paintings.

- She may have owned a turarius, an incense maker, a window cleaner and a slave who looked after a shrine.

- There were also gardeners, grooms, mule drivers, slaves to maintain and drive her carriages and litter bearers.

From fresco painters to hairdressers there was an incredible variety of jobs that slaves, freedmen and freedwomen undertook in an elite household.

Livia Drusilla as an emperor’s wife was at the very summit of Roman society but her household, whilst unusual, was not unique and other wealthy Romans had similar, if not even larger familia urbana.

Above: Detail from the painted garden fresco at the Villa di Livia 65

The long list of roles shown above only looks at the staff at her residence in Rome. She owned great country estates in Italy and quite possibly elsewhere in the Empire, she would have owned many hundreds of slaves that she had never met.

Familia Caesaris

Another intriguing group of slaves are those belonging to the emperor’s own household. Some of these were domestic or personal servants and low level administrators who would have carried out roles similar to Livia’s slaves and freed persons but in significantly larger numbers. However, an intelligent and ambitious slave raised in the Imperial household was of particular and quite unique value and could become part of the emperor’s aula, his court, and in doing so have access to, or join, his inner circle, the slaves and freedmen who helped him run the empire.

Like any royal court the emperor’s palaces were dangerous places of complex hierarchies, plots and counter plots by people in and out of favour, gossip and intrigue. The imperial slaves, freedmen and freedwomen understood how the empire functioned better than any elite Roman, senator and many rose to wield great power.

Statius, a poet in the time of the emperor Domitian, wrote a poem in AD 92 describing the career of a slave in the emperor’s court. He never mentions the slave’s name so he is known as “the father of Tiberius Claudius Estruscus”. The story of this slave is an example of who far a slave could rise, Pallas, Narcissus and Callistus are three other rags to riches stories from the same era. However, the rise of such men also suggests that emperors trusted their slaves and freedman more than they could trust elite freeborn Romans.

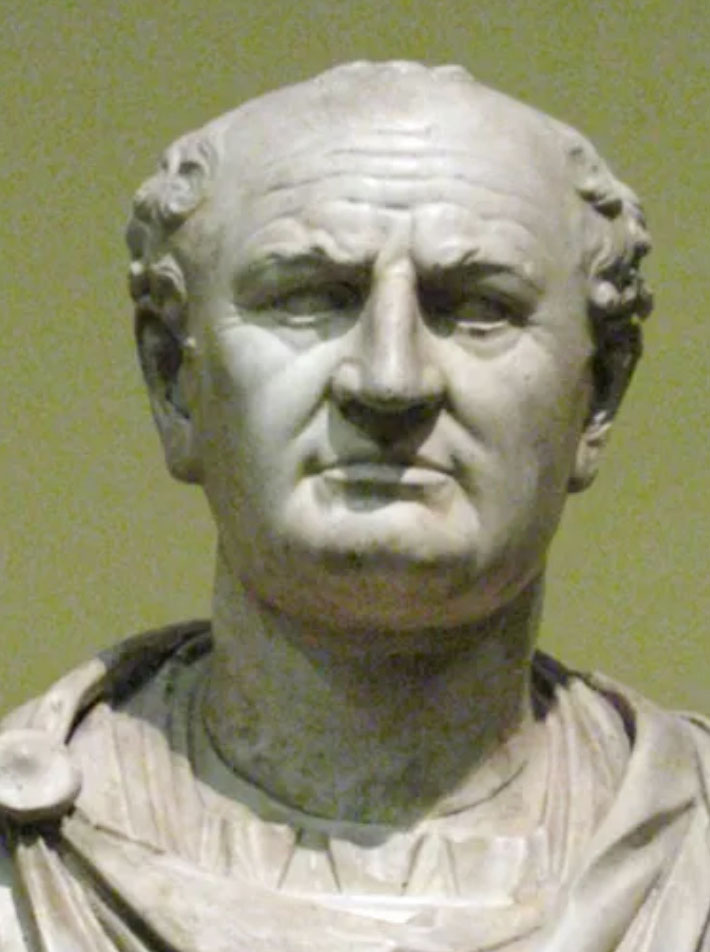

The poem describes a slave born in around AD 2 at Smyrna, modern day Izmir on the Turkish coast of the Aegean; he was sold into the household of the emperor Tiberius (left 67) for whom he initially fulfilled various domestic duties before joining the palace’s administrative team.

He must have had close contact with Tiberius because, at around the age of 30, he became a freedman without being required to purchase his freedom, an exceptional event for the time.

By the time of Caligula he accompanied the emperor to Gaul as a dispensator, a sort of paymaster responsible for paying the troops, and at some point became his personal secretary.

Claudius (right 68) raised him to the minor aristocracy as an equestrian and he married Etrusca a high born woman with whom he had two sons.

Under either Claudius or Nero, he rose to become a rationibus, a highly influential role managing the emperor’s wealth and possibly the state treasury. Perhaps the Chancellor of the Exchequer of the Empire.

He survived the infamous year of the four emperors, and came out the other side as Vespasian’s a rationibus, a role he also performed for Titus. Domitian succeeded his brother Titus in AD 81 and our ex-slave, now around 80 years old and an extremely wealthy freedman of equestrian rank was banished. He was recalled to Rome in 90 and died in 92. 69

The number of slaves and ex-slaves, i.e. freedmen, working for the emperor would have run into thousands, Trajan emperor from 98 to 117 AD probably owned in the region of 20,000 slaves although that would have included a large number of public servants such as tax collectors. 70 Apart from hundreds of remarkably specialised domestic servants there were chefs, waiters, cup bearers, tasters, people to hold napkins and people to hold a bowl if a guest felt the need to vomit. There were teachers running the schools for slave children, doctors running clinics and a small army of entertainers.

The men who administered the empire, like our unnamed friend above, were organised into departments much like modern day ministries to control finance, petitions, entertainment, the library, the water supply, etc. and each department employed teams of enslaved accountants, bookkeepers, secretaries, readers, clerks, messengers and copyists as appropriate to their role. At one point Augustus organised 600 of his slaves to form one of Rome’s first fire fighting units providing an example of the state and the emperor as a single entity, an autocracy with little or no power delegated to the senate

The emperor’s extensive farming estates, mines and quarries spread across the empire would have been administered centrally and managed locally by trusted freedmen sand laves and of course the labour force in each location would have been enslaved. Unique to the emperor were his army of tax farmers and gathers who operated in every corner of the empire collating the revenues, taking their cut, and passing the balance back to Rome.

Sexual Exploitation

What Slaves Were For

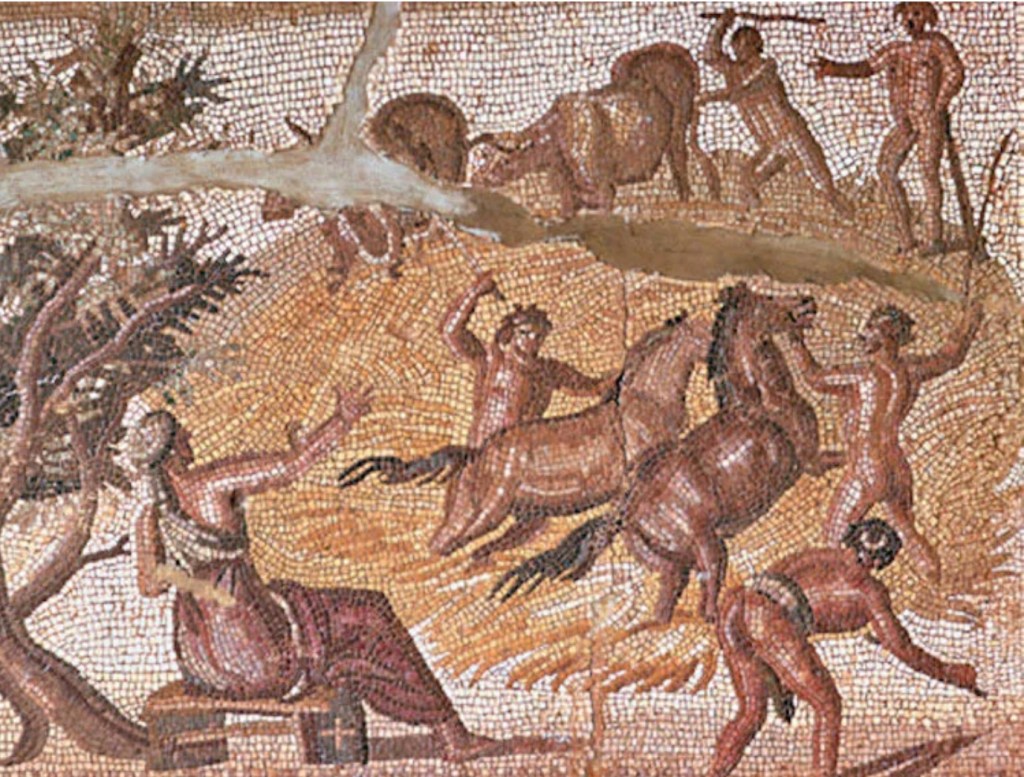

In a society that included rape in its foundation myths as in the rape of Rhea Silva by the god Mars and the rape of the Sabine women by Roman men it is not wholly surprising that sexual violence towards women and especially slaves was common. Male and female slaves were routinely sexually abused and raped by their owners and many would have been purchased specifically for that purpose.

Female slaves were expected to provide sexual services to their masters as a matter of course but they ran the risk of being punished if caught by a jealous wife despite having had no choice in the matter.

Mary Beard, as ever, puts it very succinctly:

“It was not simply that no one minded if a man slept with his slave. That was, in part at least, what slaves were for.” 73

Concubines

In cultures where slavery existed concubines were invariably enslaved women who were typically either born into slavery or purchased specifically with sex slavery in mind. In Ancient Rome the picture was more complicated as, at different times, there were laws that governed marriage and relationships between classes and between freeborn citizens and slaves.

Concubinage was recognised as a long term but not necessarily permanent relationship and became a socially acceptable way to bypass laws governing relationships or to protect the inheritance of the children from a previous marriage. However, it could also be used to disguise an abusive relationship.

The two examples below involve slaves and emperors but are very different from each other.

Antonia Caenis became Vespasian’s (right 75) lover when she was a slave owned by a member of the emperor Augustus’ inner circle.

They met when they were in their twenties and she was two years his senior. He, the son of an equestrian family, had seen military service in Thrace but was still a nonentity whilst she was on the private staff of one of the most powerful women in Rome.

Their relationship may have been continuous or interrupted by his marriage but she became his concubine, as a freedwoman, after the death of his wife somewhere between AD 52 and 66 76 and they remained together until her death in around AD 75. We cannot be sure but the relationship suggests love rather than coercion.

Antinous Farnese, was a 13 year old slave boy when he caught the 47 year old emperor Hadrian’s (right 77) eye in AD 123.

He became Hadrian’s lover, his concubinus. He was taken, maybe flaunted, at banquets and state events and travelling extensively with the emperor.

Antinous drowned around the age of 20 which might have been convenient as to have had a relationship with a man beyond that age would have been scandalous.

Today this would rightly be condemned as an abusive relationship between a middle aged man and a teenage boy made worse by the fact Antinous was the property of his abuser and had no power to resist.

Antonia Caenis

Antonia Caenis was probably a slave from the eastern mediterranean born around AD 7 78 and originally owned by Antonia Minor (left 79) the daughter of Marc Antony and Augustus’ sister Octavia. Antonia Minor grew up in the court of Augustus the man who had defeated her father. She married Livia’s son and was the mother of the emperor Cladius.

Antonia Minor was an example, along with her mother-in-law Livia, of the powerful and influential women who survived and thrived in the imperial court. She worked alongside Livia to educate the young children of the court and despite becoming a widow at the age of 27, unusually for the time she avoided being remarried and died in AD 37 at the age of 73

Antonia Caenis was trained as a secretary in Antonia’s household and was probably freed in Antonia Minor’s will in AD 37. She was Vespasian’s lover whilst still a slave and his concubine by the time he became emperor in AD 69.

Her life is not well documented but she was at the centre of Roman high politics having been close to two of the most powerful women of the age in Livia and Antonia Minor and from whom she must have learnt how to survive through the reigns of Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero and the year of the four emperors before her lover Vespasian was proclaimed by the army and senate as Imperatore.

Antonia Caenis’ memorial, an expensive altar that was possibly paid for by Vespasian, roughly translates as:

The spirit of the dead Antonia Augusta (wife of the emperor), freedwoman Caenis, the best patron of Aglaus her chief Steward.

She was famous for her intelligence, honesty, prodigious memory, loyalty and discretion. As the emperor’s concubine she was a gate keeper of great power and amassed a huge fortune, which Cassius Dio suggests was really a joint venture with Vespasian, selling:

“governorships, procuratorships, generalships and priesthoods, and in some instance even imperial decisions.” 80

Vespasian, as a new emperor and following the chaotic transfer of power from Nero through three short-lived aspirants to himself must have valued his lover’s remarkable knowledge of how the court operated and how Antonia Minor had operated as one of the most powerful women in Rome’s history.

Antinous Farnese

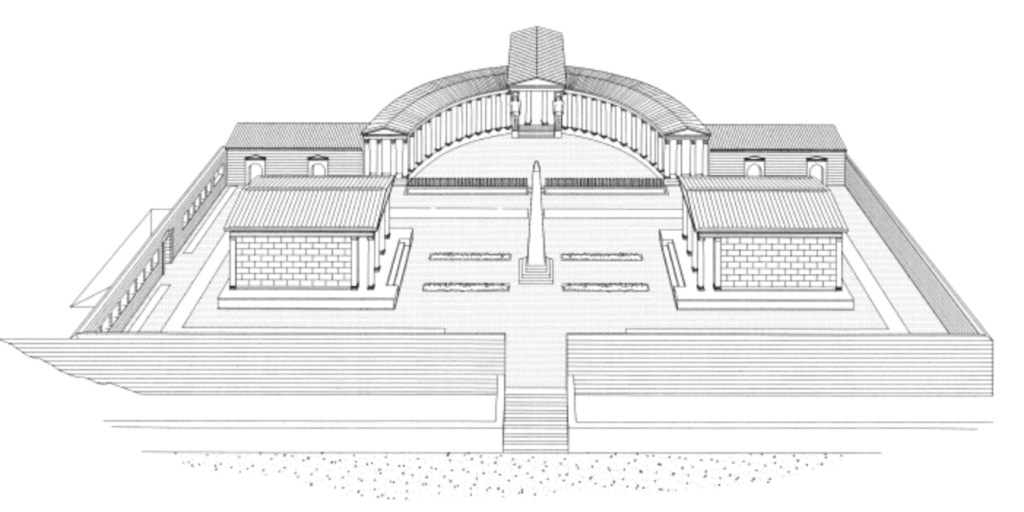

Emperors did not restrict themselves to concubines, there was also concubinus, the male equivalent; Hadrian fell in love with his slave Antinous Farnese (left 81). Antinous was born into a Greek family in Bithynium on the Black Sea in around AD 110 and it is possible that he became part of the emperor’s entourage as a young teenager when Hadrian visited in Asia Minor in AD 123.

As a strikingly good looking thirteen year old boy he presumably caught Hadrian’s eye. 82 The relationship was public with the boy accompanying Hadrian to banquets and state functions.

Relationships between elite men and boys or young men aged between 12 and 20 were acceptable as long as the boy was not freeborn thus making slaves or slave prostitutes the most common partners in such relationships.

Antinous drowned in the Nile in AD 130 at around the age of 19 or 20 whilst accompanying Hadrian on a tour of Egypt. Cassius Dio, writing his histories around 100 years later said:

“……. he had been a favourite of the emperor and had died in Egypt, either by falling into the Nile, as Hadrian writes, or, as the truth is, by being offered in sacrifice.” 83

Sextus Aurelius Victor writing even later in the middle of the 4th century suggested that Hadrian had been told he needed to sacrifice someone to prolong his own life and that Antinous had volunteered for the role. Amongst many theories it has also been suggested that Hadrian had him thrown in the Nile because he was nearing the age of 20 after which such a relationship would not have been socially acceptable.

The scandal documented by the classical writers was not the relationship, or the boy’s untimely demise but the fact that his death caused Hadrian to weep like a woman. Whatever the truth Hadrian deified Antinous, an unprecedented act at a time when only emperors and their families were added to the pantheon of Roman gods.

Below: A reconstruction based on the archaeological remains 85

He proceeded to commission temples and statues and to found cities to memorialise him across the empire; as a result, apart from Hadrian and Augustus, more likenesses of Antinous survive to this day than any other person from the classical age. 86

Antinous was worshiped as a god particularly in the eastern Empire and most strangely three years after his death had a funeral club in Rome named after him and the goddess Diana 87 so it appears that he was not only accepted as divine but by, at least, the members of that club placed on a par with the goddess of love herself. 88

It would be wrong to suggest that concubinage only exisited in the Emperor’s court. In Bergamo a funerary epitaph has been found recording an otherwise unknown provincial Roman:

“This monument is set up to the Gods of the Netherworld and to Septimius Fortunatus, the son of Gaius, and to Septimia his concubine, first a slave and then freed.” 89

Infamis, Another Form of Social Death

Prostitution was common in the Roman world, on the street, outside entertainment complexes, in cafés, at the baths, in brothels and through home visits.

The pervasiveness of sex workers or, possibly more commonly, sex slaves, in Roman society existed partly because of Roman attitudes towards extramarital relationships. The Romans, like the Greeks before them, were more concerned with protecting bloodlines than in controlling promiscuity so adultery in Rome was:

“…. limited to any sexual infidelity by a married woman or with a married woman.” 91

Wives were expected to be chaste to ensure their children could only have one possible father but men were under no legal or social obligation to be monogamous. Outside of other men’s wives and children Roman men could play the field.

It is certain that some prostitutes were freedwomen or born free but by being a prostitute they lost their rights as a citizens and in effect were demoted to the same status as slaves. The Tabula Heracleensis, 92 a set of municipal regulations possibly drafted by Julius Caesar, states:

“No one shall be admitted among the decurions and the conscripts in the senate of any municipality, colony, prefecture, market, or meeting place of Roman citizens, nor shall anyone who comes under the following categories be permitted to express his opinion or to cast his vote in that body:

……… anyone who prostitutes his body for gain; anyone who trains gladiators or acts on the stage or keeps a brothel.” 93

To be excluded from society in this was to become infamis, of ill fame.

The other citizens who became infamis under the same regulations included: thieves, gladiators, fraudsters, debtors, exiles, people found guilty of a crime in their local court, men dishonourably discharged from the Army and bounty hunters.

A pretty disreputable lot.

There is a perception that, because elite men had access to their own slaves, the customers of prostitutes were from the lower classes but one example suggests that this is misleading; Cicero argued that Publius Clodius Pulcher, a politician from a patrician family, was immoral because he spent too much money on male and female prostitutes.

Courtesans

We also know that there were high class prostitutes or courtesans working in the upper echelons of Roman society although whether they worked for money or influence is unclear. One such woman, Vulumnia Cytheris had been owned by an equestrian by the name of Publius Volumnius Eutrapelus who had organised for her to be trained as an actress 94, a profession in which she became famous.

From the “House of the Tragic Poet” Pompeii. 95

She was Eutrapelus’ mistress when a slave and when she was manumitted and became a freedwomen he passed her on to Caesar’s close supporter, Mark Antony, but she probably continued to sleep with Eutrapelus who was now her patron. Under the laws documented on the Tabula Heracleensis she was infamis for having worked on the stage regardless of whether she was now working as a high-class prostitute. According to Plutarch, Mark Antony was already unpopular with the masses even before he started flaunting his courtesan:

“They loathed his ill-timed drunkenness, his heavy expenditures, his debauches with women, his spending the days in sleep or in wandering about with crazed and aching head, the nights in revelry or at shows, or in attendance at the nuptial feasts of mimes and jesters.

Sergius the mime also was one of those who had the greatest influence with him, and Cytheris, a woman from the same school of acting, a great favourite, whom he took about with him in a litter on his visits to the cities, and her litter was followed by as many attendants as that of his mother.” 96

Cicero was horrified and wrote to one of his friends:

“The Tribune of the Plebs (Mark Antony) was borne along in a chariot, lictors crowned with laurel preceded him; and in the middle of these, on an open litter, was carried an actress; whom honourable men, citizens of the different municipalities, coming out from their towns under compulsion to meet him, saluted not by the name by which she was well known on the stage, but by that of Volumnia.

A carriage followed full of pimps; then a lot of debauched companions; and then his mother, utterly neglected, followed the mistress of her profligate son, as if she were her daughter-in-law.

O the disastrous fecundity of that miserable woman! That man stamped every municipality, and prefecture and, in short, the whole of Italy with the marks of such wickedness as this.97

She was eventually executed when her plan to overthrow Claudius was discovered.

On another occasion Cicero attended a dinner party where Cytheris was reclining below the host as if she was the materfamilias. Cicero’s point to his friend Paetus was that it was acceptable to have a relationship with a courtesan providing Eutrapelus could say “I own her but I am not owned by her.” 99 As ever it was an issue about degrading manliness, honour and status not a moral issue of cavorting with an ex-slave, actress and courtesan.

Later she became the mistress of Marcus Junius Brutus, one of Caesar’s assassins and of Cornelius Gallus who became the governor of Egypt. Cicero called her, “that miserable woman” and as infamis gave her little or no respect but when he was marooned in Brundisium after the civil war having picked the wrong side he approached Cytheris to find out from Mark Antony when it would be safe for him to return to Rome.

The Army: Wives, Slaves and Prostitutes

The lines between Roman slaves, courtesans, concubines and prostitutes are blurred and women could acquire unwarranted labels through no fault of their own by falling foul of the Roman ideals of morality.

Any permanent military base, whether in Italy or the provinces quickly gained a vici or canabae, a civilian settlement that grew up outside the fort. These vicus housed traders, bars, food stalls and inevitably prostitutes. However, when a legion was in the same place for any length of time the vicus also housed the soldiers’ partners and children; soldiers were forbidden to marry so any relationship, however long-lasting was, in the eyes of the law, informal.

Some of these women followed their husbands from previous postings and some would have been Roman citizens but a significant number of soldiers’ “wives” came from local Romanised communities or were themselves the daughters of soldiers. However, they had no formal status and their children were not Roman citizens unless they came into the world after their father was discharged.

This situation led to an unpleasant reality; if a commander decided to “clean up” the vici along side his camp he evicted the women regardless of their status. When Aemilianus took over the army in Spain he evicted 2,000 “prostitutes” from the canabae and it is more than likely that many of these women were not sex workers but the informal wives of the soldiers in the camp.

A soldier based far from home was unlikely to meet the girl of his dreams around the camp and there is evidence that a common solution was to buy a slave girl rather than engage the servcices of prostitutes. Some of these master-slave relationships lasted and the soldier made his slave a freedwoman to enable a formal marriage after he retired from the service. Gaius Longinus Cassius, a vetran of the fleet based at Misenum near Naples went further. In his will he freed and left his estate to two women, Marcella and Cleopatra, and to Cleopatra’s daughter Sarapais. It is reasonable to assume that that the two women shared his bed and that Sarapais was his daughter. 101 Another example of a funerary epitaph found in Austria says:

“Gaius Petronius, son of Gaius, from Mopsistum, lived 73 years and served 26 in the cavalry wing Gemelliana. He lies here. Urbana, his freedwoman and wife, set this up.” 102

Urbana had been Petronius’ slave before he freed and married her.

Working Girls

Prostitutes were often slaves who were sold into prostitution by their owner or, in some cases, by their family. We cannot know how common it would have been for a master to sell a slave to a pimp but it was common enough for Hadrian to introduce legislation to limit a master’s right to do so, although he set the bar very low:

“He forbade a master to sell a male or female slave to a pimp or to a gladiator trainer without first showing good cause.” 103

McGinn argues that prostitution was a highly profitable enterprise with even low-classed prostitutes earning three times the wage of a male labourer. As a result it was an attractive business in which to invest for the owners of slaves, landlords and pimps. 104

A brothel prostitute probably had limited freedom and was confined to the brothel for most of her working life. Her range of services and fees were no doubt dictated by the brothel owner who would have seen her as a commodity that he could hire out for profit. A street walker might appear to have more freedom but in practice was probably under the control of a pimp or a criminal gang.

There are differing views as to the number of brothels in Pompeii, only one building appears to be built for the purpose (see right).

It seems especially seedy, five small booths each equipped with a masonry bed and erotic pictures above their entrances.

There is a toilet and an upstairs floor that’s purpose is unclear. The booths have plenty of graffiti scrawled on their walls.

The fact that Pompei only appears to have one purpose build brothel in the two thirds of the city that has so far been excavated is misleading as 35 other buildings or rooms have been identified as possible sites for sex workers to have plied their trade. All but one of these buildings probably had a primary function other than prostitution operating as inns, lodging houses, taverns and restaurants and the sex on offer was perhaps often, but not always, provided by the staff. 105

If there were 35 brothels plus street walkers and sex workers operating from bars and hotels there appear to have been a large number of prostitutes working in a town of just 10,000 people.

Knapp estimates that one in every 100 people living in Pompeii was a prostitute; a ratio that obviously would have been much higher amongst women aged bewteen 16 and 29. 106

Brothels or the many other places where sex could be purchased are not easily identified in the excavations of Roman cities partly because of the wide range of establishments mentioned above and partly because many were probably operating out of lower-class residential areas.

An inscription found at Aesernia, modern Isernia, in central Italy shows that hostelries offered more than food and drink:

“Innkeeper, my bill please

You had one sexatrius (about 1/2 litre) of wine, one as worth of bread, two asses worth of relishes.

That’s right.

You had a girl for eight asses.

Yes, that’s right.

And two asses worth of hay for your mule.

That damn mule will ruin me yet.” 107

An as was 1/10th of an denarius and as mentioned elsewhere we can use a conversion rate of 1 denarius to 69 British pounds to see an equivalent modern value. The man’s bill was roughly £21 for food, £14 for hay and £55 for sex with the landlord’s prostitute.

McGinn suggests that prostitutes were working on a part-time or fulltime basis in public spaces outside facilities such as circuses, amphitheatres and temples regardless of whether anything was taking place inside. 108

Sex and the Baths

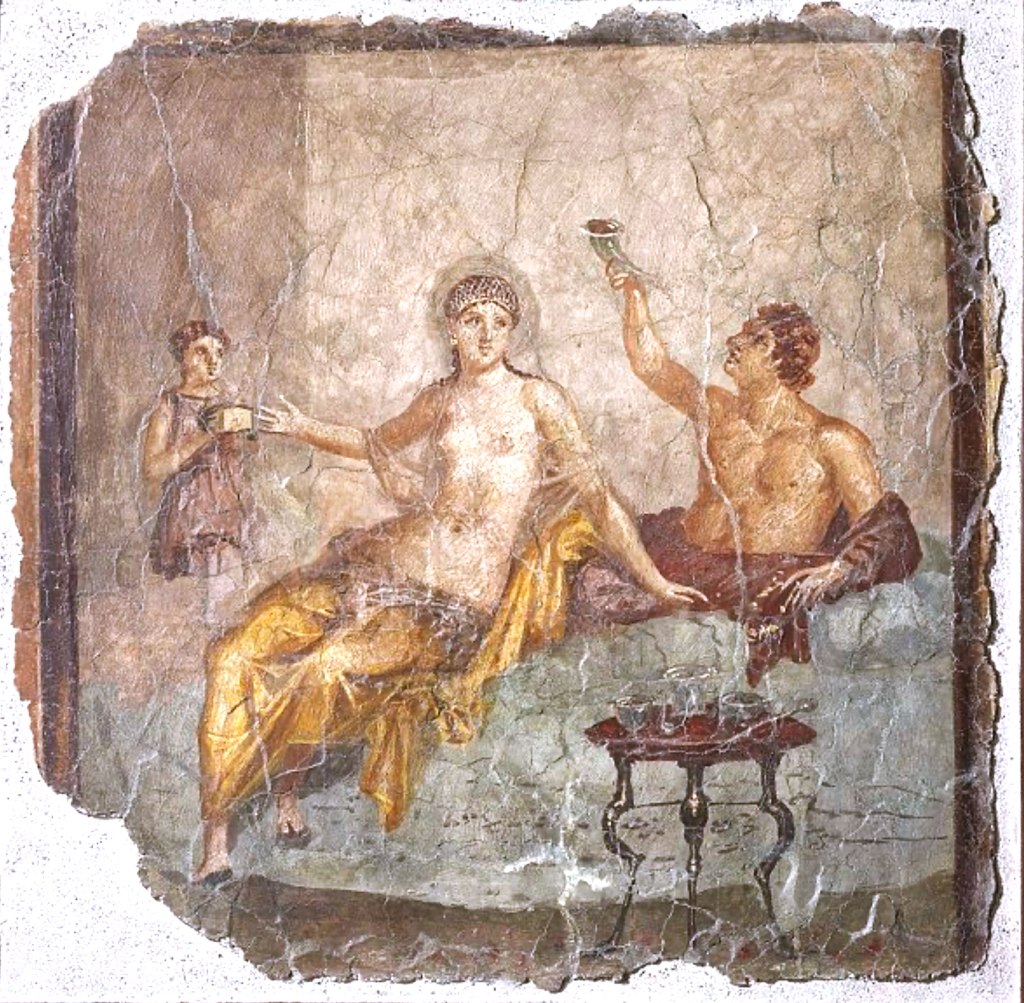

Fresco from Agrippa’s Villa in Trastevere 109

There were over 1,000 public baths in Rome as well as many private establishments and a reasonable clue into what could take place in either is that a number of early Christian writers, including Clement of Alexandria, warned his readers to avoid such places because of mixed bathing that he believed led to promiscuity. He was particularly concerned that slaves could become aroused when bathing their owners. 110

The baths were a fundamental part of Roman life and the wide range of both public and private establishments meant that bathing was available to most people. They went to the baths for exercise and to move through the succession of warm, hot and cold baths but also to gamble, gossip with friends, talk business, drink wine and enjoy snacks. It also seems that some people visited the baths to find sexual partners or to buy sex.

Some baths had separate facilities for men and women but mixed bathing was common. Nudity and alcohol has always been a potent mixture so it is not surprising that the baths were lucrative territories for prostitutes; some may have been independent and perhaps this was the case at public baths but private baths are far more likely to keep such services in-house.

Ammianus Marcellinus, a native of Antioch in the 4th century , wrote a history of Rome. He believed that Rome had become deeply stained and overwhemed by incurable vices and comments on the behavour of elite men who arrive at the baths accompanied by fifty slaves:

“And if they suddenly find out that any unknown female slave has appeared, or any worn-out courtesan who has long been subservient to the pleasures of the townspeople, they run up, as if to win a race, and patting and caressing her with disgusting and unseemly blandishments, they extol her, as the Parthians might praise Semiramis, Egypt her Cleopatra, the Carians Artemisia, or the Palmyrene citizens Zenobia.” 112

The phrases “worn-out courtesan” and “unknown female slave” almost certainly refer to the prostitutes who worked the baths.

In the changing room, apodyterium, at the Suburban Baths at Pompeii there are eight erotic scenes painted on the wall above what archaeologists believe were shelves for patrons to leave their clothing, there is evidence that there were once sixteen paintings and associated shelves. They show couples, or in one case a threesome, engaged in various sexual acts. It is unclear whether they are just humorous, simply examples of erotic art, or whether they suggest, or advertise, what will happen once the client has undressed and left the changing room.

The most convincing theory is that they advertised a brothel upstairs in the same building and therefore probably operated by the same person or persons.

The epitaph on the tomb of Tiberius Claudius Secundus reads, in part:

“bathing, wine, sex ruin our bodies,

but bathing, wine and love make life worth living”. 114

It is apparant that male and female prostitution was very common in Rome and in all Roman towns and cities.

I would appreciate hearing your thoughts on this subject.